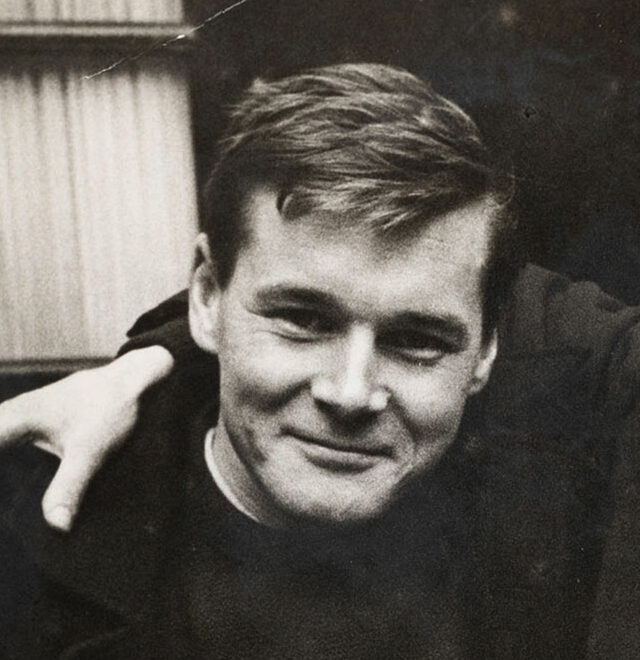

“Moi je l’aimais beaucoup Simon. Je me sentais auprès de Simon dans le réel de la pensée vivante. […] Il était toujours très sobre, très remarquable, et c’était merveilleux. Il passait son temps à travailler. Je sais que c’était quelqu’un de très honnête et vrai, pas toujours en train de chercher la gloire au bout du pinceau. Que la gloire vous retienne ou pas, ça ne vous empêche pas d’être un excellent peintre. […] C’était un bon peintre qui mériterait que l’on sorte ses tableaux de l’ombre. […] Et moi je pourrai ramener les voiles d’un souvenir, ce qu’une soirée dans cet atelier m’apportait…”

Anne de Staël, le 11 décembre 2023

“Je suis né à Nice le 10 février 1932. Mon père m’a dit que c’était la nuit où l’on immolait par le feu l’effigie en carton pâte de Sa Majesté Carnaval, final tragi-populaire des fêtes du Carnaval en liesse. J’ai un moment cherché une signification à la coïncidence de cet événement et de ma venue au monde – mais ayant constaté que j’étais plutôt sujet aux refroidissements et autres rhumes, j’ai rapidement cessé toutes spéculations en ce sens.”

— Simon de Cardaillac, le 26 juin 1988

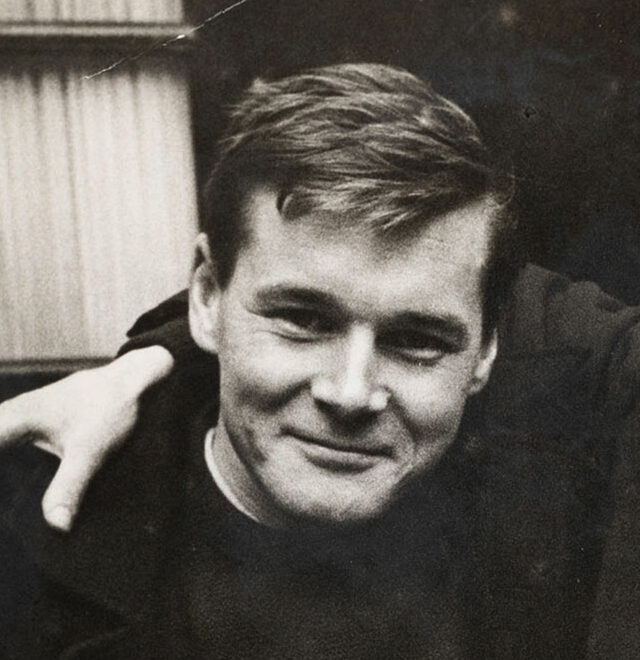

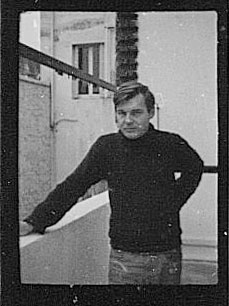

Dès sa naissance, Simon de Cardaillac a baigné dans le monde de l’art. Sa mère, Jeanne de Cardaillac, était élève aux Arts décoratifs de Nice avec Jeannine Guillou, sa grande amie, alors mariée à Nicolas de Staël. C’est Jeanne de Cardaillac qui, en 1940 alors que Jeannine Guillou est en danger du fait de sa citoyenneté polonaise résultant de son précédent mariage avec Olek Teslar, porte à Vichy une requête de Jeannine demandant sa réinscription dans les registres de l’État français. Véritable amie de confiance de cette dernière, elle fait partie des rares personnes présentes lors du baptême d’Anne, la fille de Nicolas de Staël et de Jeannine Guillou.

“Seul le noyau des amis d’enfance assiste au baptême, célébré par l’abbé Krebs. Il y a là Jeanne de Cardaillac, la marraine, et son fils Simon.”

Laurent Greilsamer, Le Prince foudroyé, la vie de Nicolas de Staël, Fayard, 1998, p.97

Les relations étroites entre les deux familles offrent à Simon de Cardaillac l’opportunité de grandir au contact de Nicolas de Staël et de sa famille, façonnant durablement son œil d’artiste.

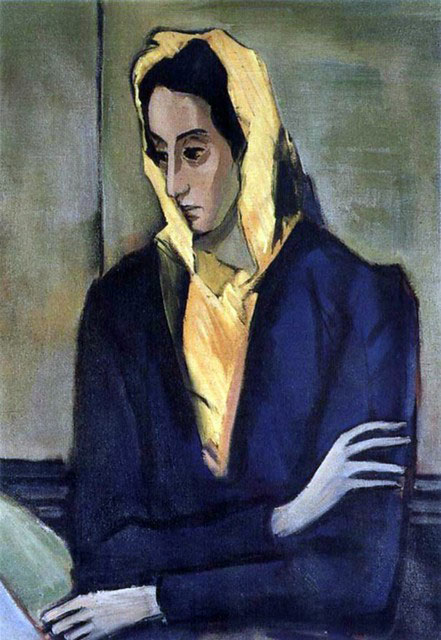

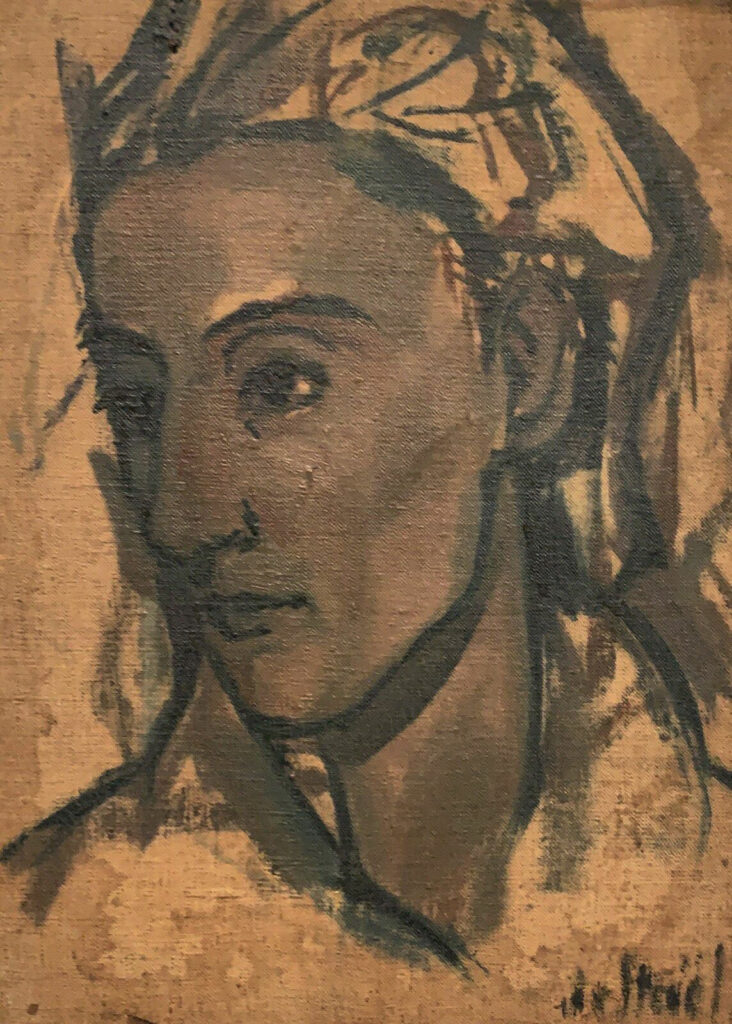

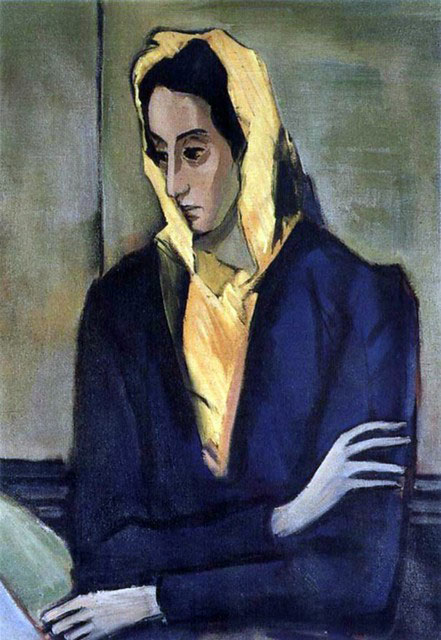

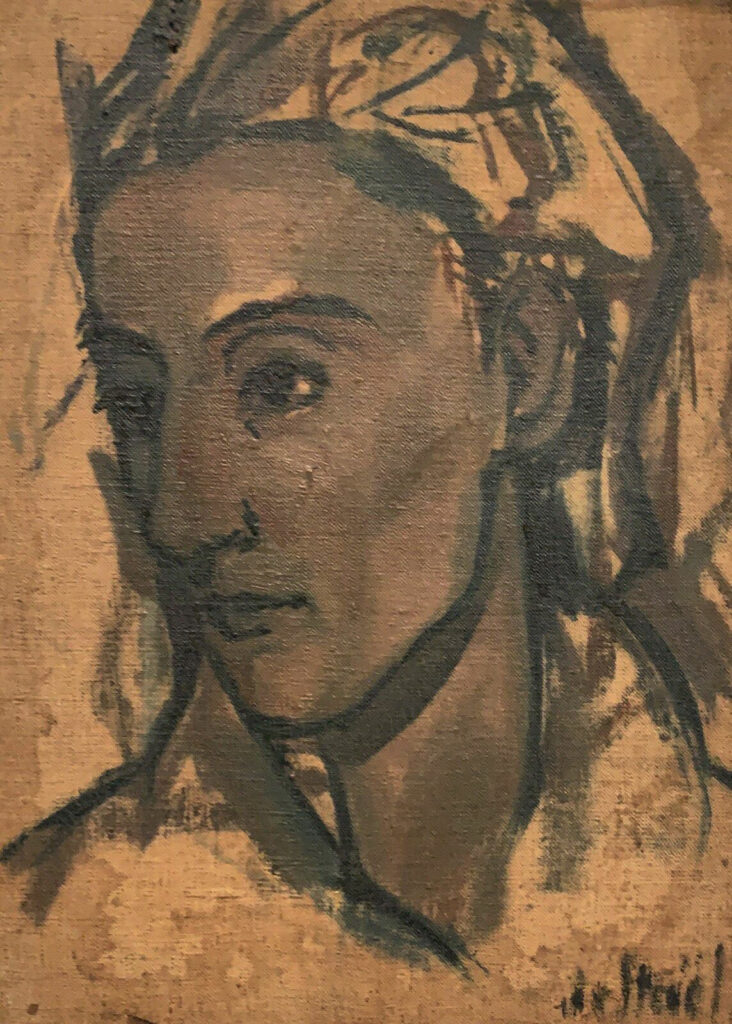

Ces longues heures passées chez les Staël eurent quelques incidences sur l’oeuvre de Nicolas de Staël – en témoigne l’existence des deux rares portraits de Jeannine Guillou au fichu jaune. En effet, alors que Jeanne de Cardaillac assistait à l’élaboration du premier des célèbres portraits de Jeannine Guillou peint entre 1941 et 1942 par Nicolas de Staël, celle-ci demanda au peintre de stopper son travail :

“Ne touchez plus à ce tableau, Nicolas ! Par pitié, il est parfait. Tout Jeannine est là, s’exclame Jeanne de Cardaillac lors d’une visite impromptue.

- Jeanne ! je commence tout juste…

- Si vous donnez un autre coup, vous démolissez tout !”

Staël rit. Voilà que le destin s’interpose avant même qu’il aille au bout de ses forces. Jeanne, je vous l’offre. Il est pour vous…”

Laurent Greilsamer, Le Prince foudroyé, la vie de Nicolas de Staël, Fayard, 1998, p.99

Le tableau rejoignit ainsi le domicile familial des Cardaillac qui vécut sous le regard de Jeannine Guillou pendant de nombreuses années. Quant à Nicolas de Staël, il peignit un second portrait.

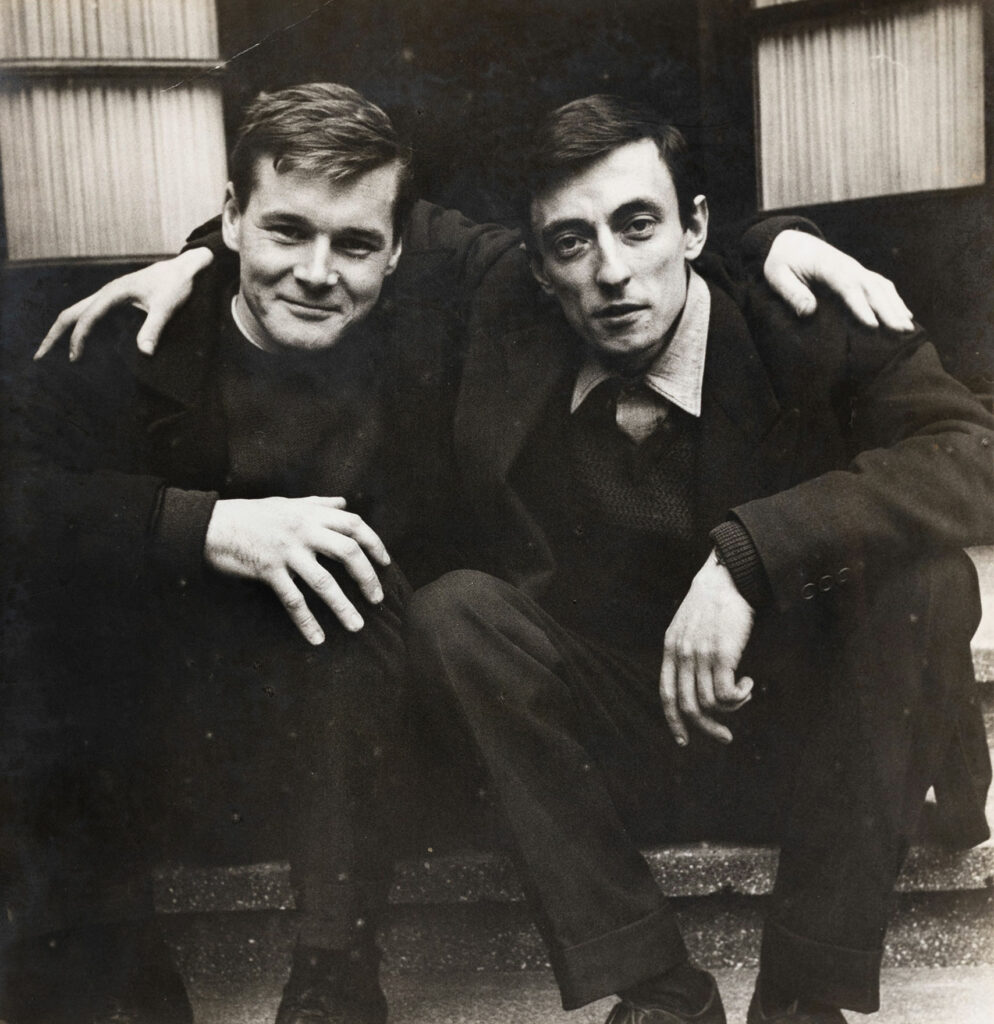

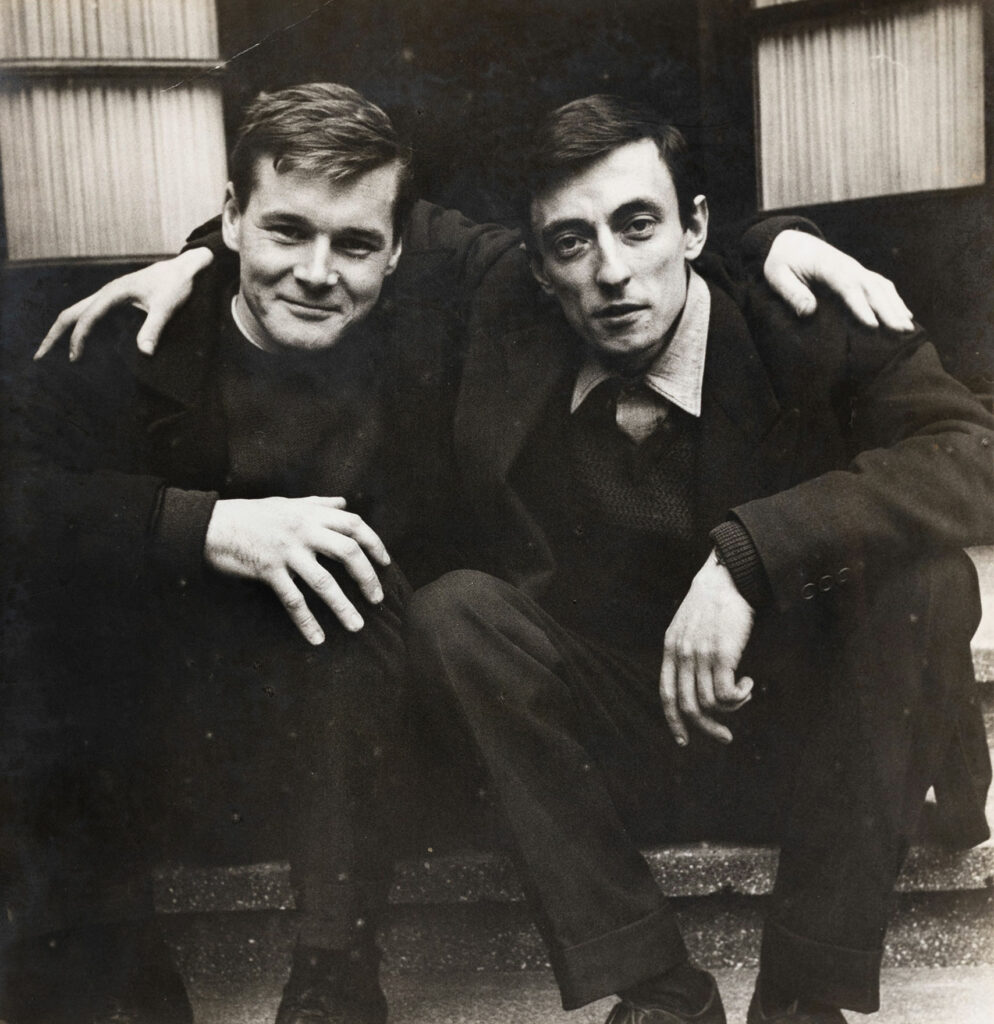

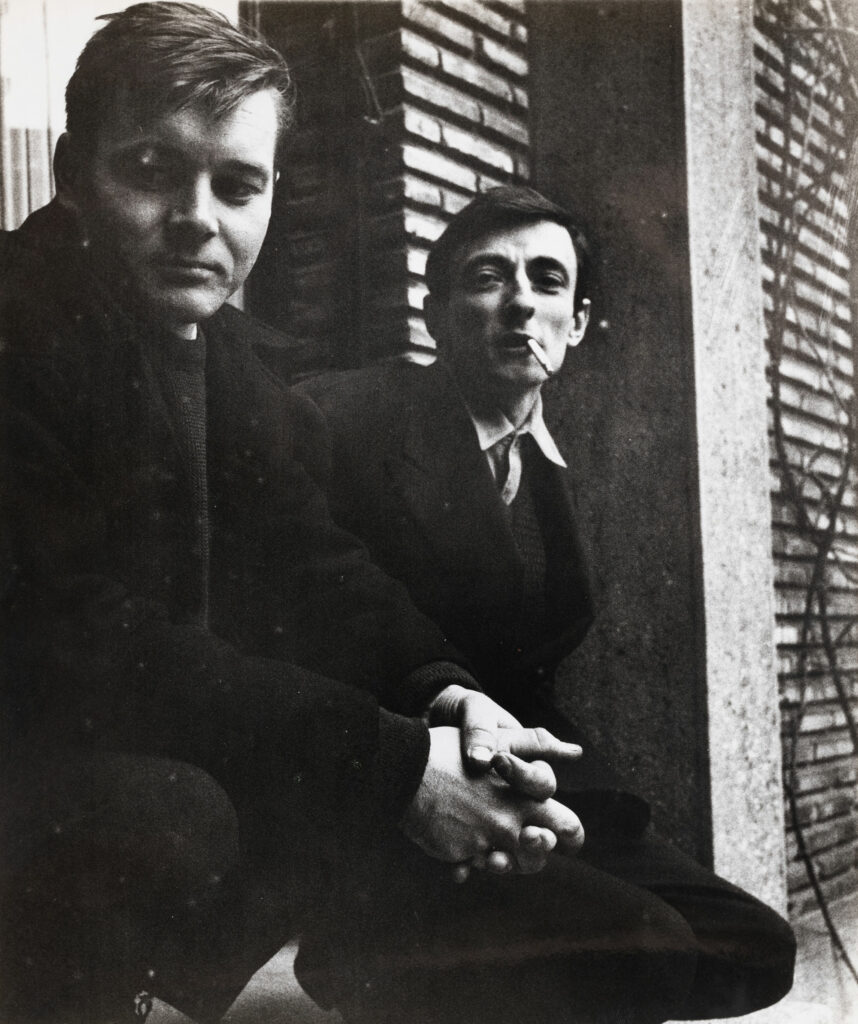

Durant son enfance, Simon de Cardaillac est particulièrement proche d’Antoine Tudal, dit Antek, le fils que Jeannine Guillou a eu avec Olek Teslar. N’ayant qu’un an de différence, ils grandissent ensemble et vivent même à plusieurs reprises sous le même toit. Antoine Tudal passe notamment le terrible hiver 1946, celui qui emporta sa mère, chez les Cardaillac à Saint-Gervais[1]. Les vies des deux garçons sont particulièrement liées jusqu’à l’âge adulte. Pour l’anecdote, ils ont tous les deux été initiés à la nage par Nicolas de Staël qui les propulsa du haut du rocher de Roba Capeo de Nice. Comme nous l’apprend Anne de Staël, son père lui fit vivre la même expérience, ce qui la terrifia, bien que sa mère l’attendait dans l’eau pour la réceptionner[2].

[1] Laurent Greilsamer, Le Prince foudroyé, la vie de Nicolas de Staël, Fayard, 1998, p.156

[2] Entretien avec Anne de Staël, le 11 décembre 2023

“A Nice, Staël avait conduit Antek et son ami Simon de Cardaillac au rocher de Roba Capeo qui surplombe la mer. Il s’était déshabillé, avait demandé aux gamins d’en faire autant, et avait projeté Antek dans les flots. Simon, qui s’était refusé à se dévêtir, reculait quand Staël l’avait saisi et jeté à son tour à la mer. Minuscule bouchon, Antek avait nagé à la façon des chiots ; Simon, lui, commençait à boire la tasse et à couler. Staël avait alors plongé au secours des deux marmots, les poussant vers le rivage et concluant : “Vous voyez, vous savez nager maintenant !”

Laurent Greilsamer, Le Prince foudroyé, la vie de Nicolas de Staël, Fayard, 1998, p.129

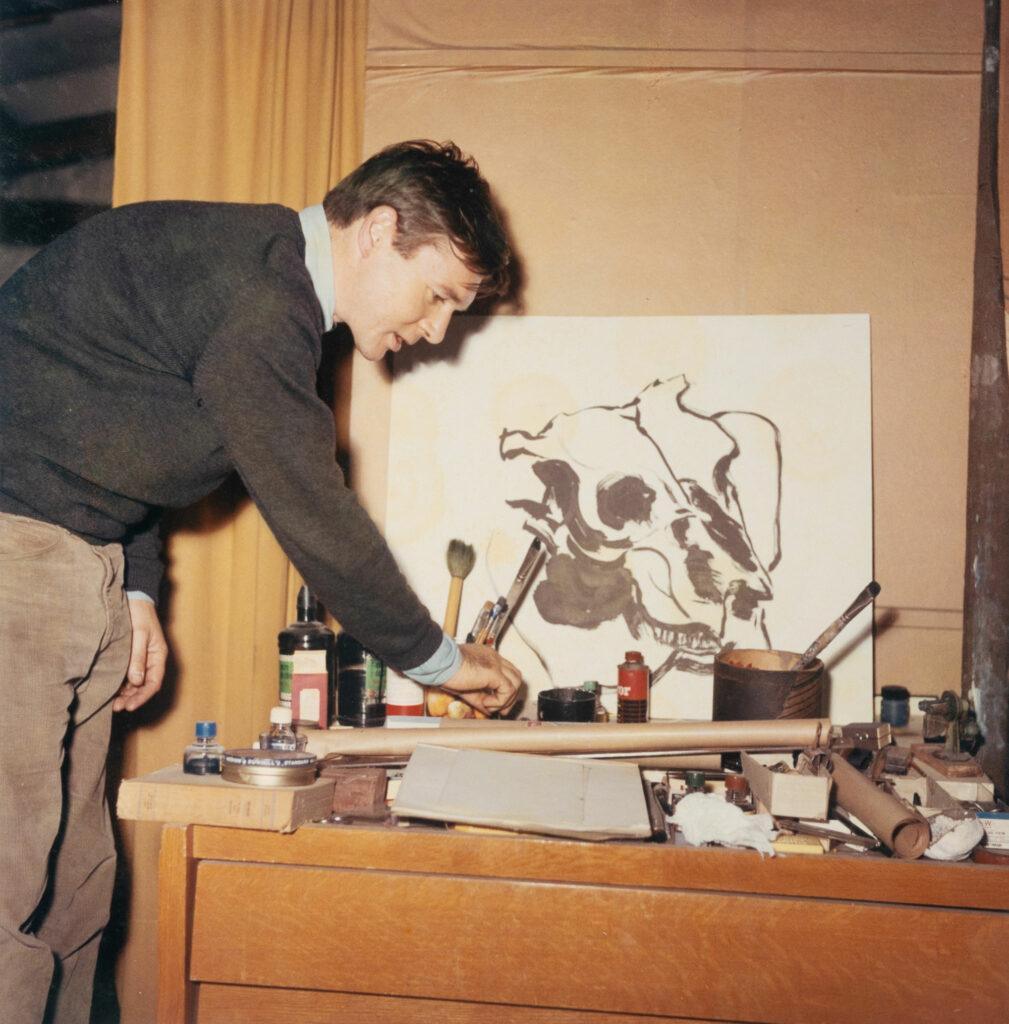

A l’âge adulte, c’est en grande partie grâce à Antoine Tudal que Simon de Cardaillac s’installe à Paris après des études aux Arts décoratifs de Nice, en section architecture.

“Je “monte” à Paris invité par un ami écrivain [Antoine Tudal] qui percevait qu’il fallait que je fasse de la peinture. Mon existence bascule, recommence […] Ici commence la Peinture.”

Simon de Cardaillac, note manuscrite du 26/06/1988

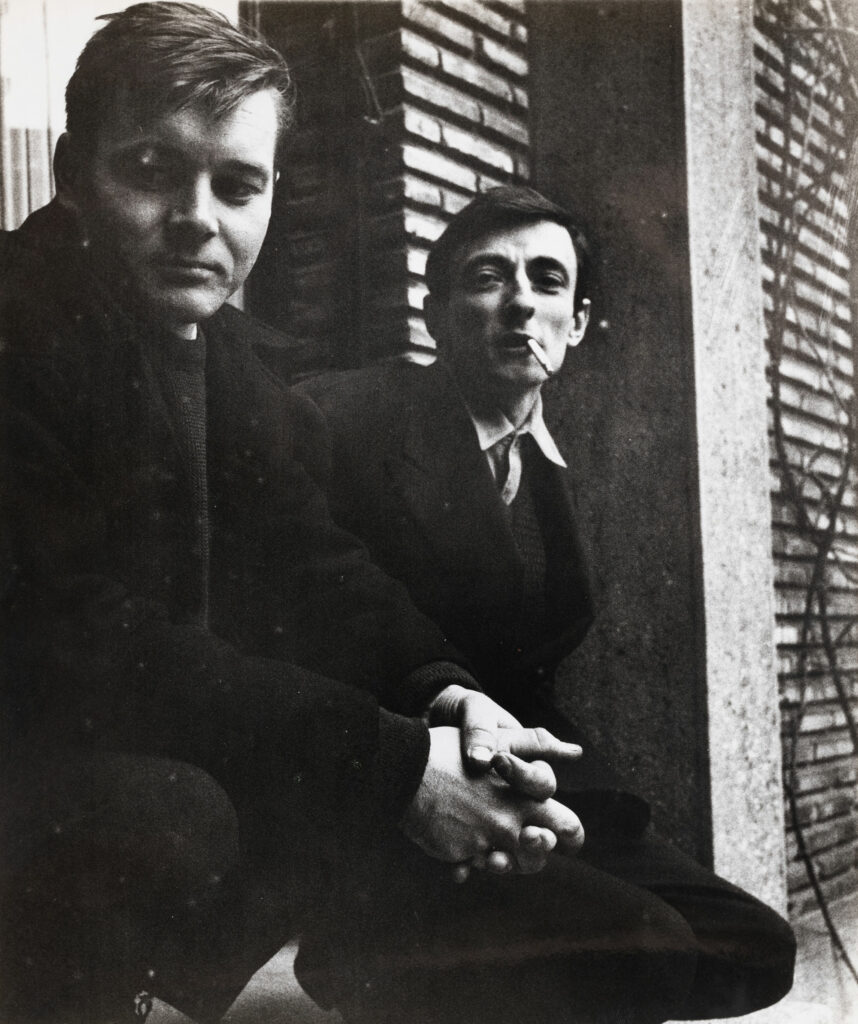

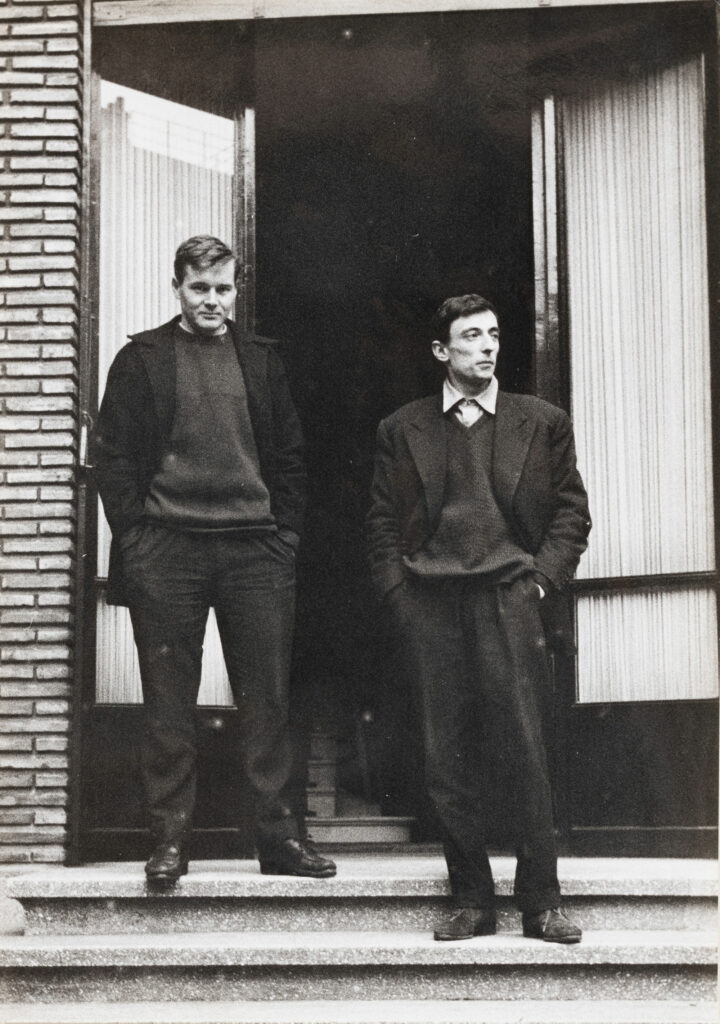

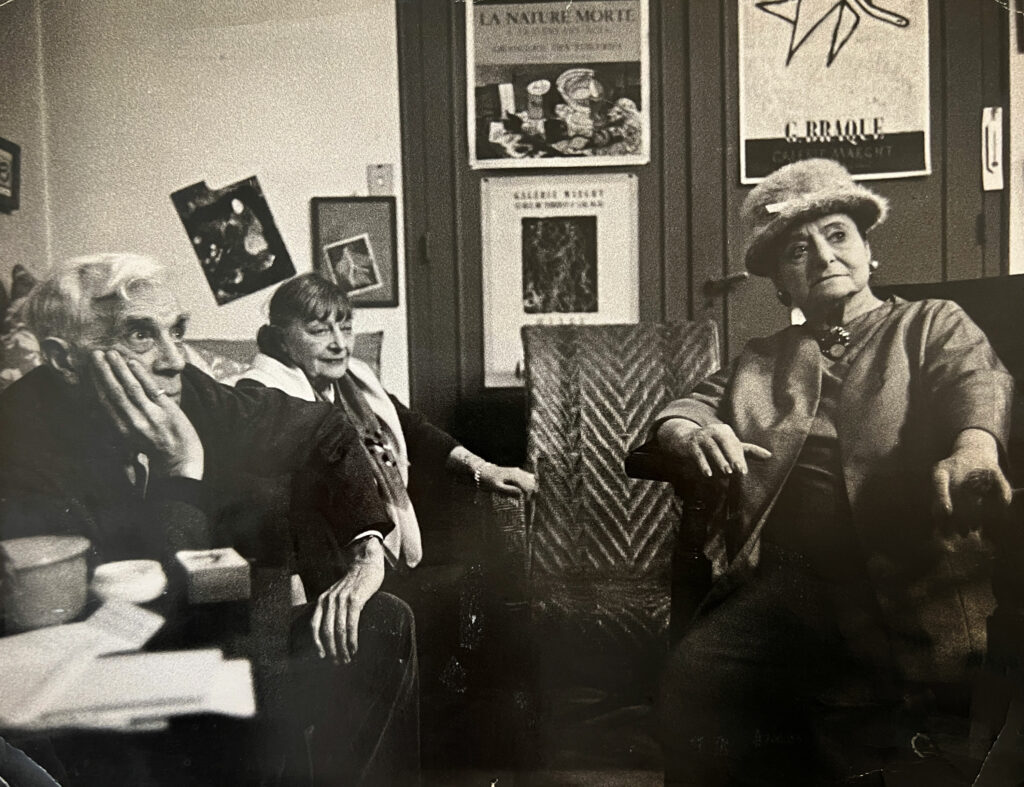

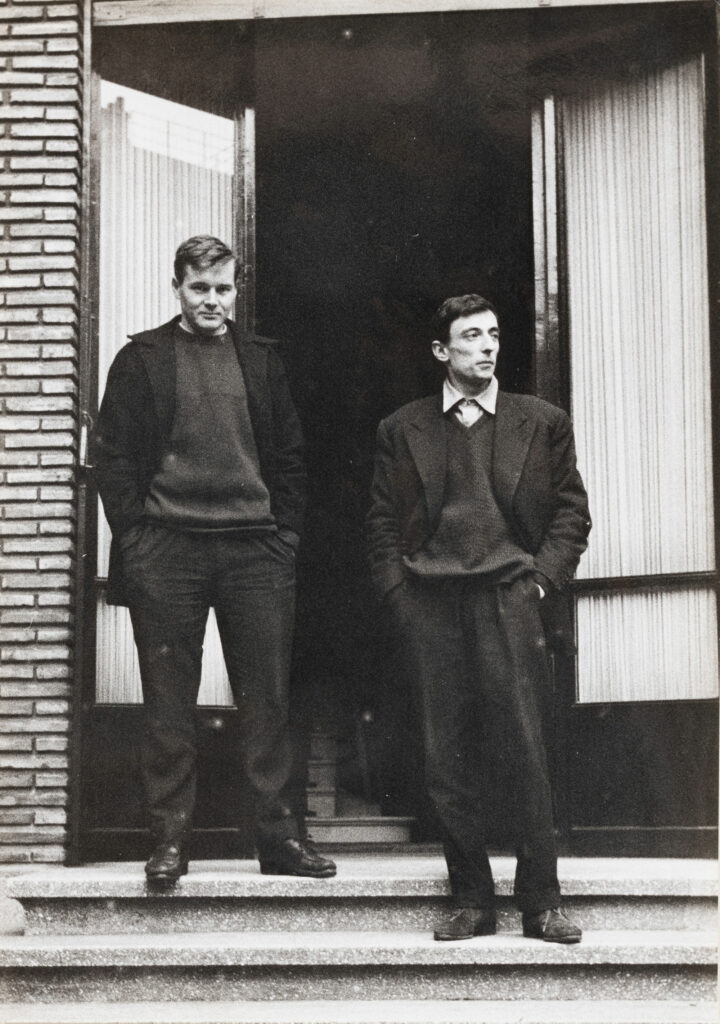

A Paris, Simon enchaîne les visites de musées, galeries et les rencontres. Antoine lui présente notamment Georges Braque. Débute alors une longue série de visites dont témoignent un certain nombre de photographies.

“Georges Braque, par l’intermédiaire d’un ami, voit mon travail et m’encourage. Fréquentes visites chez le (Vieux) Maître, toujours bien accueilli, ce sont des moments fantastiques et inoubliables pour un jeune peintre.”

Simon de Cardaillac, note manuscrite du 26/06/1988

C’est notamment Georges Braque qui pousse Simon de Cardaillac à exposer[3] en 1956 au 11e Salon des Réalités Nouvelles qui se tenait au Beaux-Arts de Paris (du 29 juin au 5 août 1956), aux côtés d’artistes de renom tels que Pierre Alechinsky, Jean Arp, Sonia Delaunay ou Hans Hartung. Il nouera par la suite une amitié avec Alechinsky et Hartung.

Au cours de ces visites chez Braque, Simon entame une profonde amitié avec Mariette Lachaud, l’assistante de Georges Braque, auteur et férue de photographie.

[3] Chris Evers Gallery, Hus for Nutidskunst, Klampenborg, 07/1988 et Simon de Cardaillac, note manuscrite du 26/06/1988

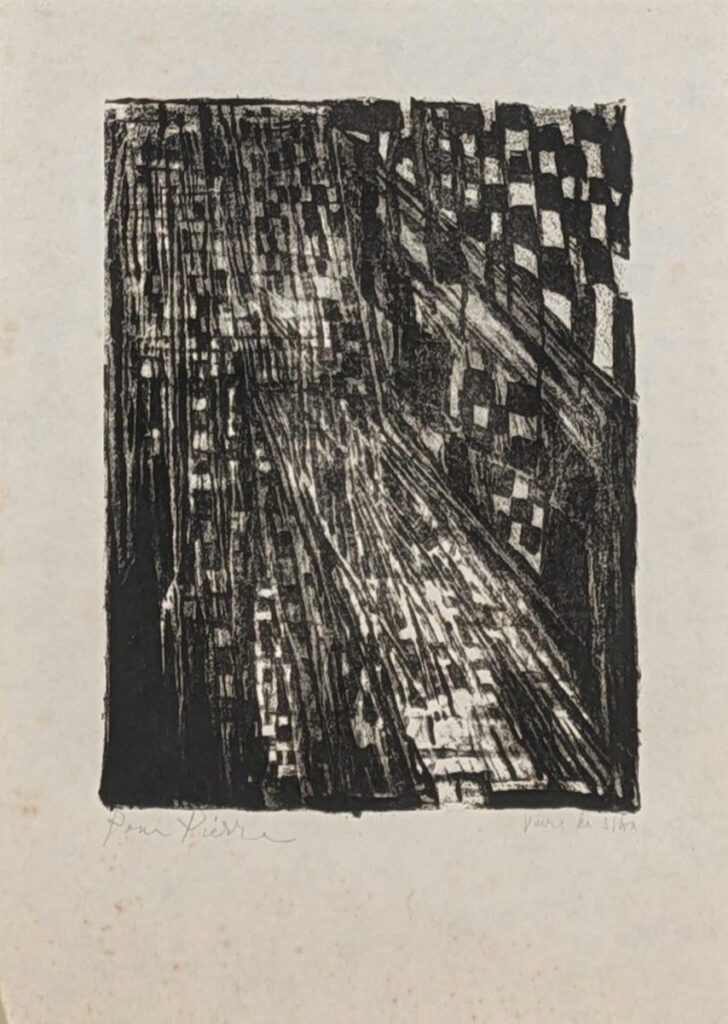

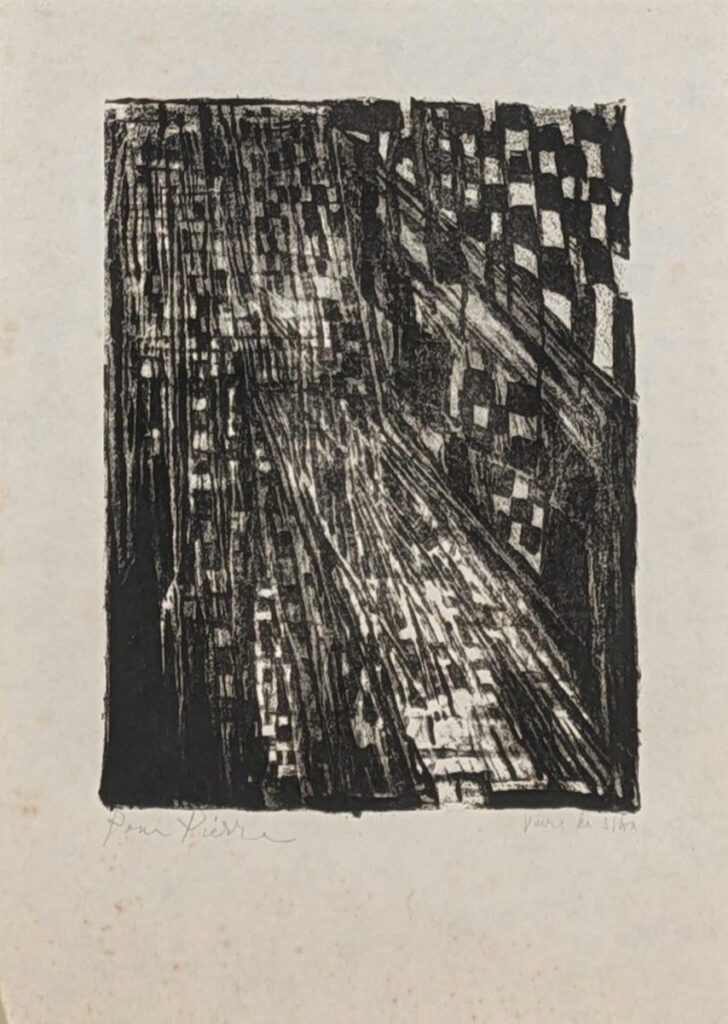

A cette époque, Antoine Tudal a déjà publié plusieurs écrits dont Souspente (1945), un recueil de poèmes rédigé à seulement 12 ans alors qu’il est puni et contraint par ses parents de rester dans une mansarde durant six mois. Très bien accueillis, ses poèmes furent illustrés par Georges Braque. Cet événement encouragea Antoine Tudal à continuer d’écrire. Il proposa à Simon de Cardaillac de réaliser les gravures d’un recueil intitulé Simagrées.

“A vingt-trois ans, il [Antoine Tudal] se décide à apporter à un éditeur un manuscrit que voici, Tempo, puis un autre, Simagrées, qui paraîtra prochainement avec des eaux-fortes d’un peintre qui a le même âge que lui, Simon de Cardaillac.”

Antoine Tudal, Tempo, Librairie Gallimard, 1955, p.3

A cette occasion, Simon montre ses peintures à de Staël qui l’encourage alors à les graver.

“Il [Nicolas de Staël] se rend à Sèvres pour voir Antoine Tudal et Simon de Cardaillac. Simon commence à peindre. Il regarde ses lavis noir, blanc et gris, ses essais de bande dessinée, et l’encourage : “Quoi qu’on fasse, il faut le faire bien.”

Laurent Greilsamer, Le Prince foudroyé, la vie de Nicolas de Staël, Fayard, 1998, p.263

Confiant dans l’entreprise de Simon, de Staël le recommande à Johnny Friedlaender qui a ouvert, en 1949, un atelier de gravure fréquenté par les plus grands artistes de l’Ecole de Paris, dont Maria Helena Vieira da Silva et Zao Wou-Ki.

“Je travaille sur un projet d’illustration d’un texte poétique, Nicolas de Staël m’encourage à les réaliser en gravure et me recommande pour que j’aille travailler dans l’atelier de Johnny Friedlaender. Je m’initie à la gravure sur cuivre.”

Simon de Cardaillac, note manuscrite du 26/06/1988

“Je participe en 1956 au Salon “Comparaisons” et au Salon des “Réalités Nouvelles”. Puis vient la guerre d’Algérie, je suis rappelé dans l’armée – lumières et expériences humaines différentes – pas de place pour la peinture sous le soleil et dans la poussière blanche. De retour à Paris, il faut se guérir des cauchemars mais je recommence vite à peindre. Un collectionneur belge s’intéresse à ma peinture. Un peu d’argent pour travailler. Des collectionneurs américains arrivent ensuite. Tout va bien. Je vis de ma peinture.”

Simon de Cardaillac, note manuscrite du 26/06/1988

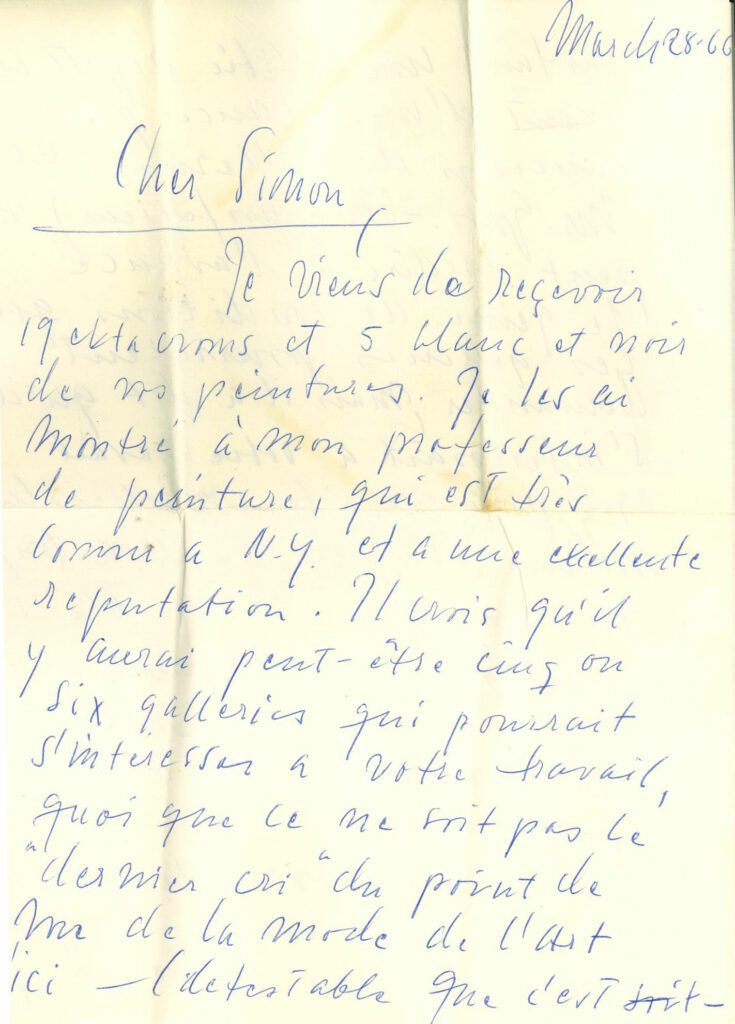

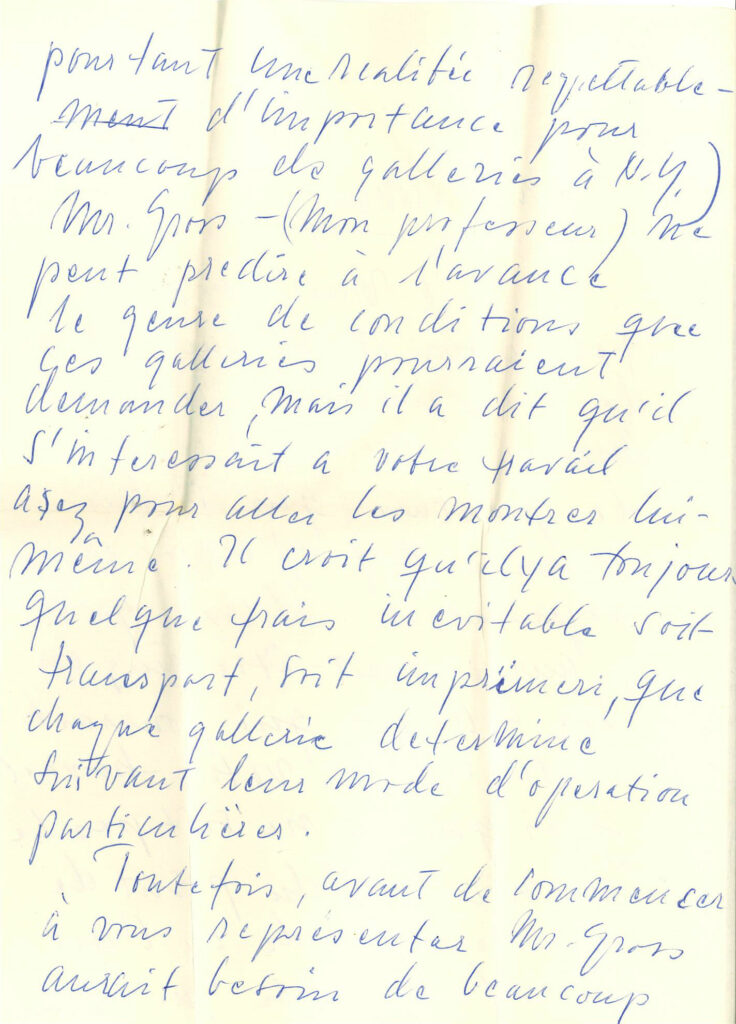

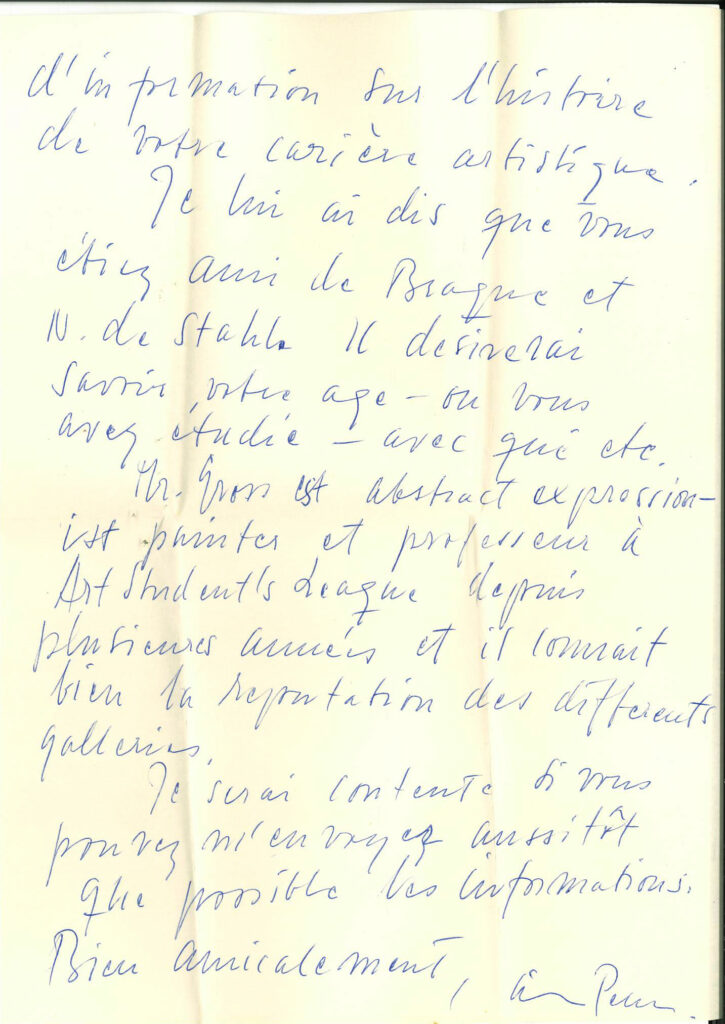

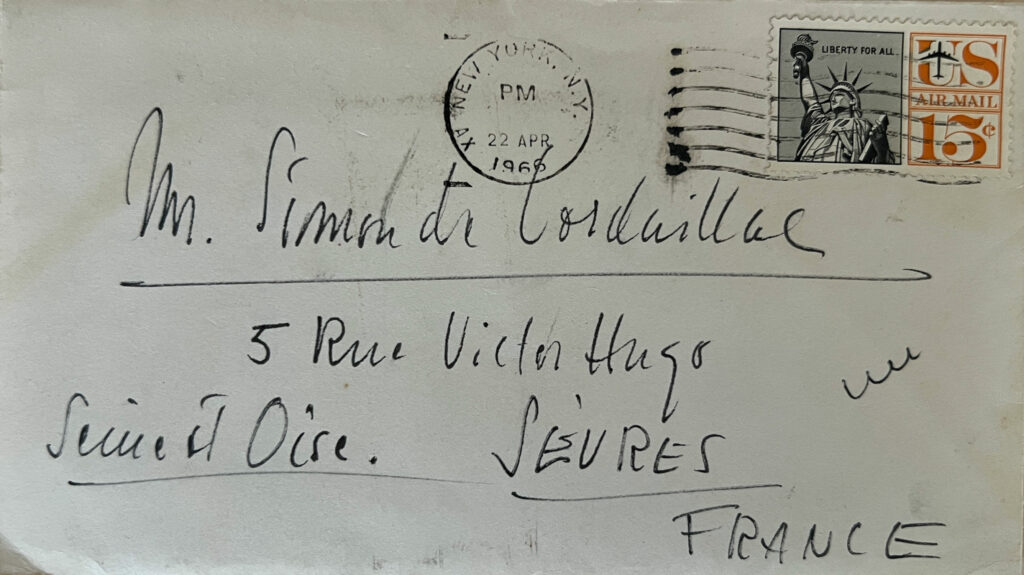

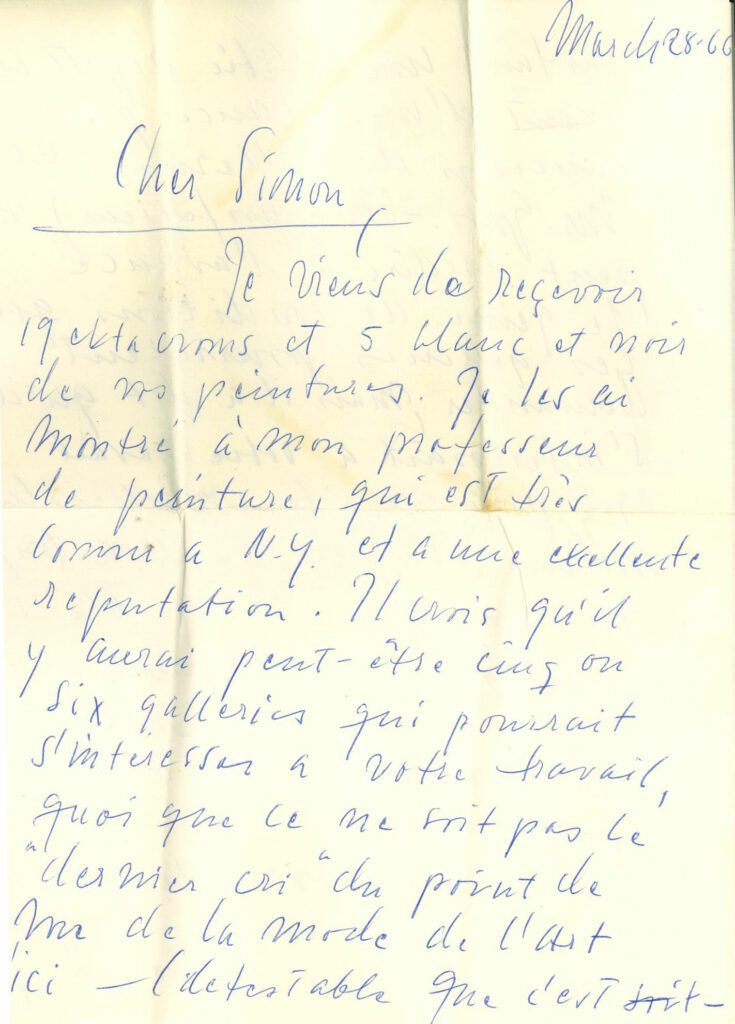

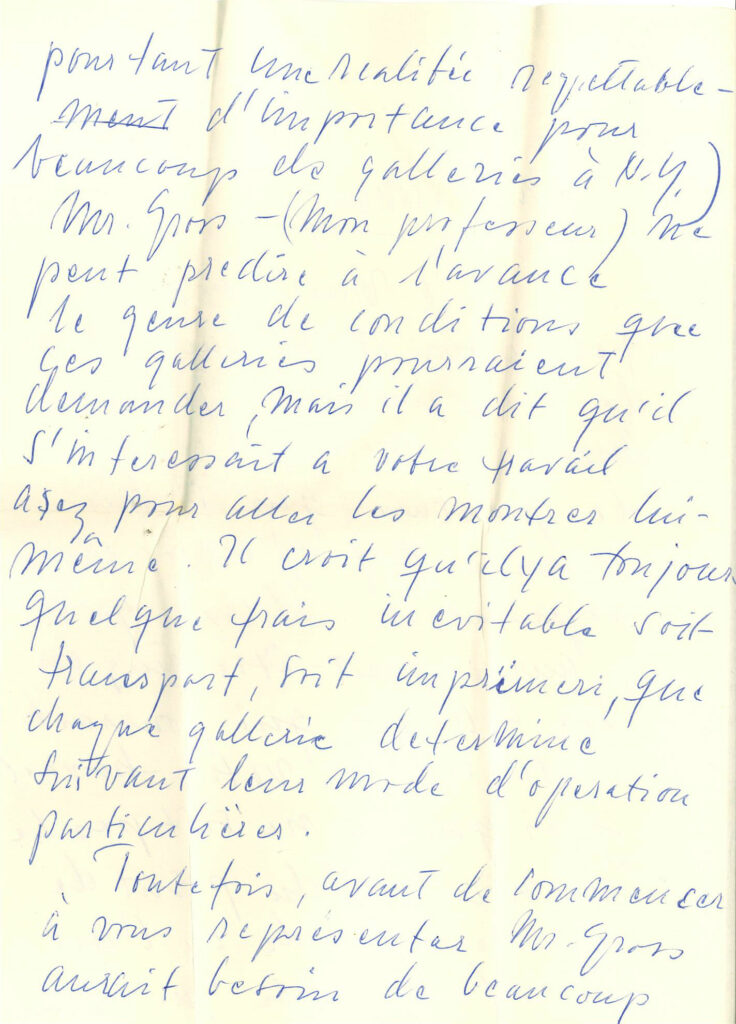

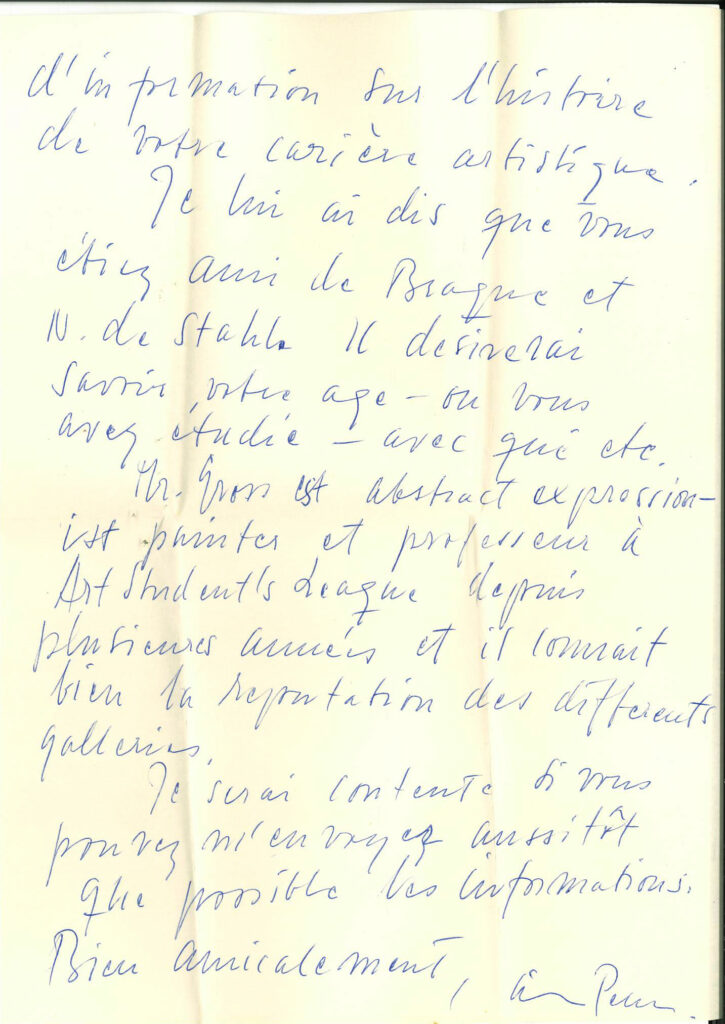

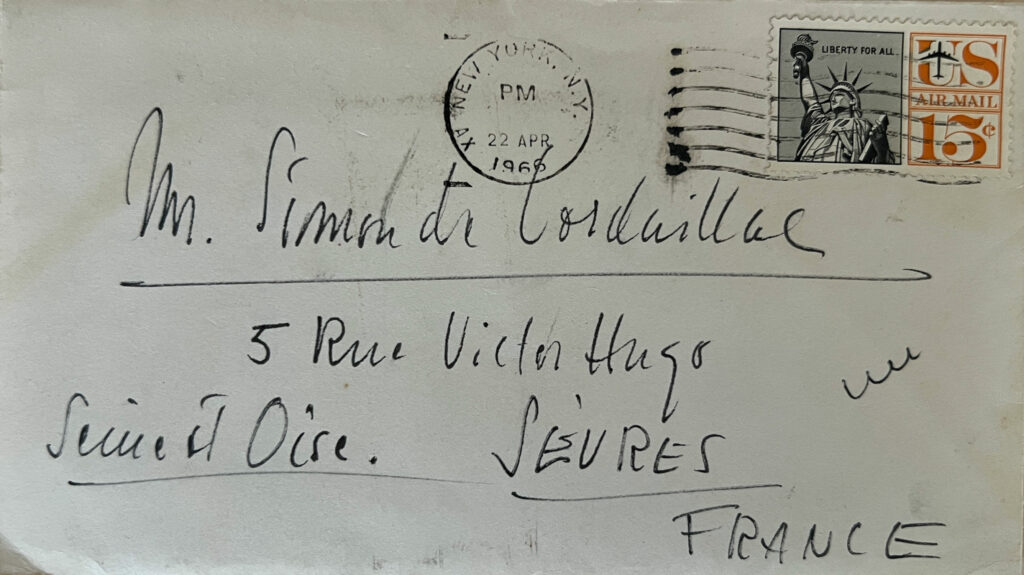

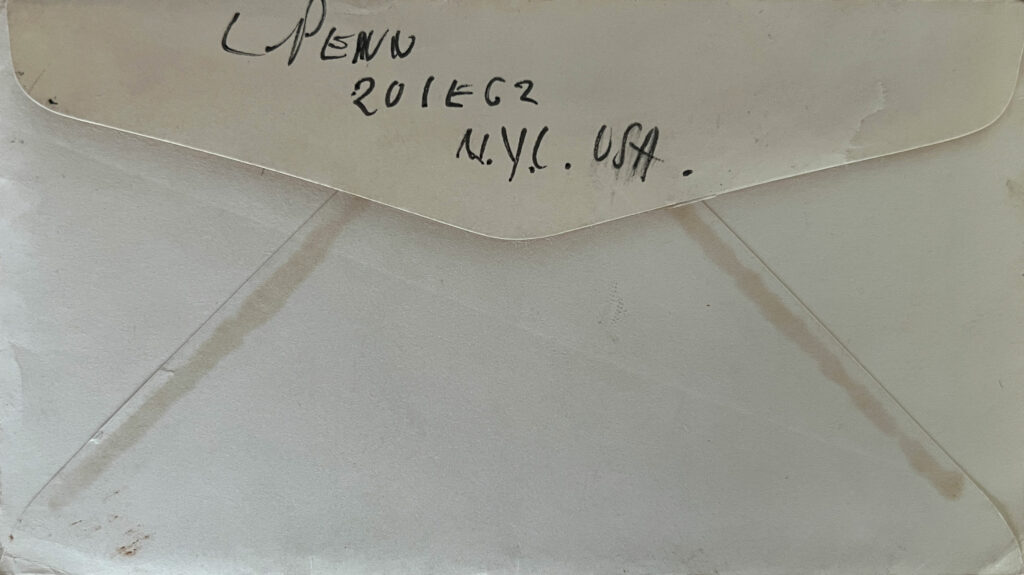

Après avoir été enrôlé dans l’armée au moment de la guerre d’Algérie, Simon de Cardaillac entame une période de création intense et commence à faire parler de lui. A cette époque, les galeristes et collectionneurs américains jouent un rôle déterminant sur le marché de l’art. Plusieurs d’entre eux sont séduits par le travail de Simon de Cardaillac. L’un des premiers à repérer son talent est le célèbre photographe Irving Penn. En 1966, il lui demande de lui envoyer un échantillon représentatif de ses œuvres afin de les montrer au peintre expressionniste abstrait, Sidney Gross, professeur de peinture à l’Art Student’s League of New York depuis 1960, “très connu à N.Y. et [qui] a une excellente réputation”. Sidney Gross, intéressé par la production de Simon de Cardaillac, choisit de se rendre en personne dans les galeries susceptibles de présenter ses œuvres.

“Il crois qu’il y aurai peut-être cinq ou six galleries qui pourrait s’intéresser a votre travail, […] il a dit qu’il s’interessait a votre travail assez pour aller les montrer lui-/même.”*

Retranscription non corrigée d’une lettre en français d’Irving Penn du 28 mars 1966

Par ailleurs, un courrier d’Irving Penn du 13 juin 1966 nous apprend que Peter Findlay de Findlay Galleries était également intéressé par le travail de Simon de Cardaillac.

“Please contact Peter Findlay of Findlay galleries interested in your paintings at hotel de la Tremoille Paris greetings Penn”

Télégramme d’Irving Penn, le 13-6-66

La galerie exposait alors des artistes de notoriété internationale comme Fernand Léger, Edward Hopper, Le Phô, Bernard Buffet, Frank Stella ou Roberto Matta.

Dans un télégramme du 25 juin 1966, Irving Penn fait cette fois-ci référence à une galerie de Palm Springs projetant d’exposer Simon de Cardaillac :

“Ses personnes qui doivent venir pour sélectionner des peintures pour leur galerie de Palm Springs (californie) s’appellent M et Mme Linsk – Kristofer vous téléphonera s’ils arrivent en mon ‘inconscience’”

Retranscription non corrigée d’une lettre en français d’Irving Penn du 25 juin 1966

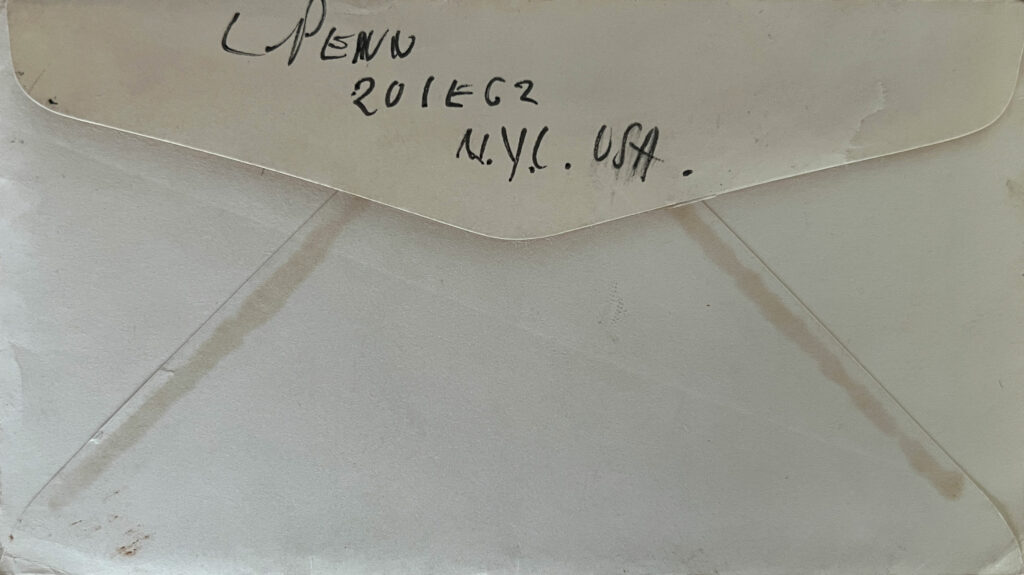

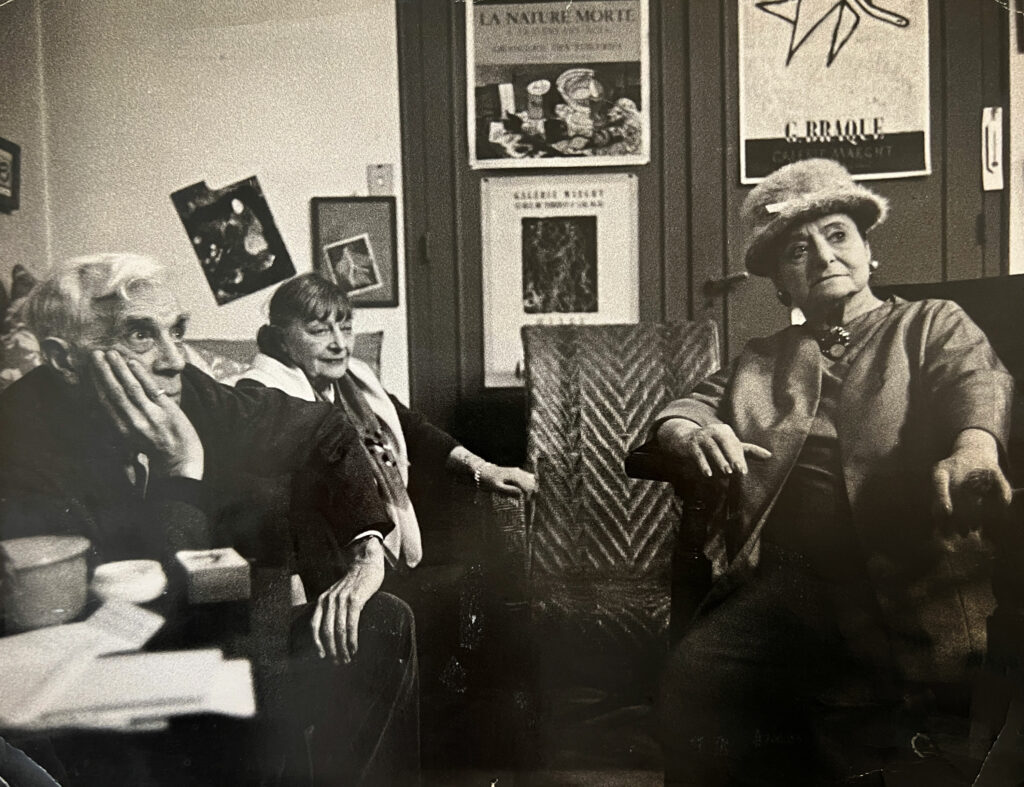

En outre, on retrouve à la même époque des œuvres de Simon de Cardaillac dans de grandes collections américaines, telles que celle de Helena Rubinstein. Cette dernière possédait en effet un tableau de 1960 intitulé Le plan de soleils, représentant une “Abstraction in tones of gray, green and white”[1]. Simon de Cardaillac a très probablement connu Helena Rubinstein, car il conservait dans ses archives personnelles une photo de 1960 figurant Georges Braque, Marcelle Lapré et Helena Rubinstein dans le studio de Braque. Cette photo complète d’ailleurs une série de photos de même format que l’on retrouve dans la collection de Helena Rubinstein.

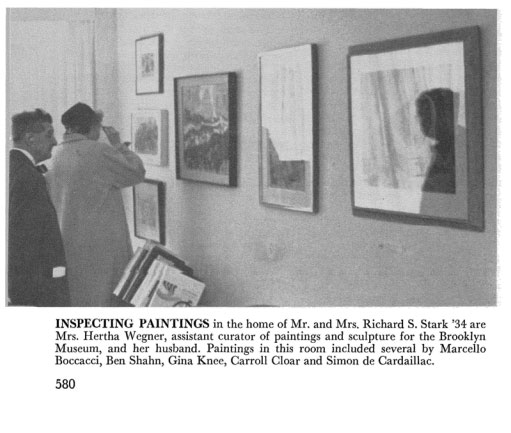

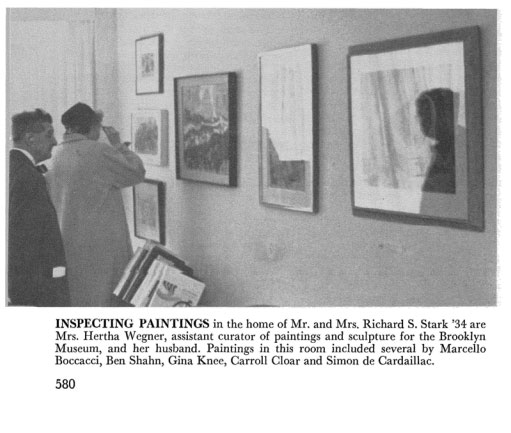

On sait également qu’une peinture de Simon de Cardaillac se trouvait dans la collection du présentateur et animateur de télévision Richard S. Starck, comme en atteste une exposition organisée en 1961 dans son appartement new-yorkais et visitée notamment par Hertha Wegner, conservateur des peintures et sculptures du Brooklyn Museum[2].

Il faut croire que Simon de Cardaillac commençait réellement à se faire connaître dans le milieu mondain new-yorkais de l’époque, puisque le comédien Charles Bronson acquit aussi l’un de ses tableaux[3]. On peut également apercevoir un de ses tableaux dans l’appartement new-yorkais du couple Cowles, sur une photographie publiée dans le volume 124 de la revue House&Garden en 1963.

[1] The collection of Helena Rubinstein, New York, Paris and London, Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, 1966

[2] Cornell Alumni News, 15 mai 1961, vol.63, n°16, p.580

[3] Entretien avec Jeannine de Cardaillac, fille de Simon de Cardaillac, novembre 2023

Toutefois, malgré des débuts prometteurs sur le marché américain, Simon de Cardaillac décida au cours des années 1960 de prendre un nouveau départ artistique et de cesser progressivement ses collaborations.

“J’ai l’impression d’être prisonnier de quelque chose qui m’empêche de travailler comme je le désirerais. Je décide alors de rompre mes engagements avec les uns et les autres et de repartir à zéro. Je cherche du travail.”

Simon de Cardaillac, note manuscrite du 26/06/1988

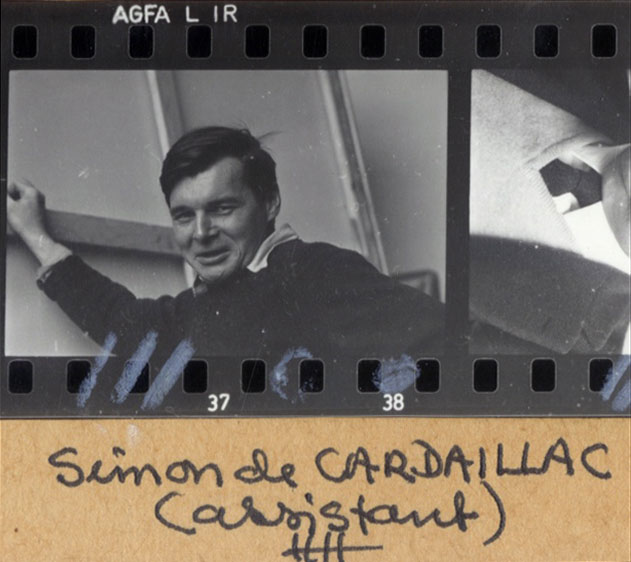

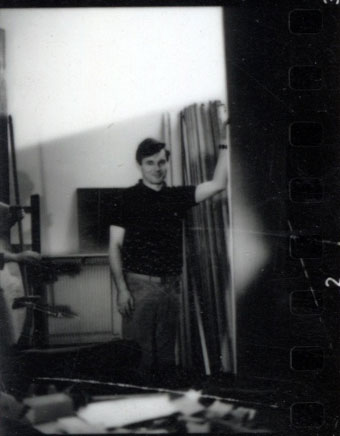

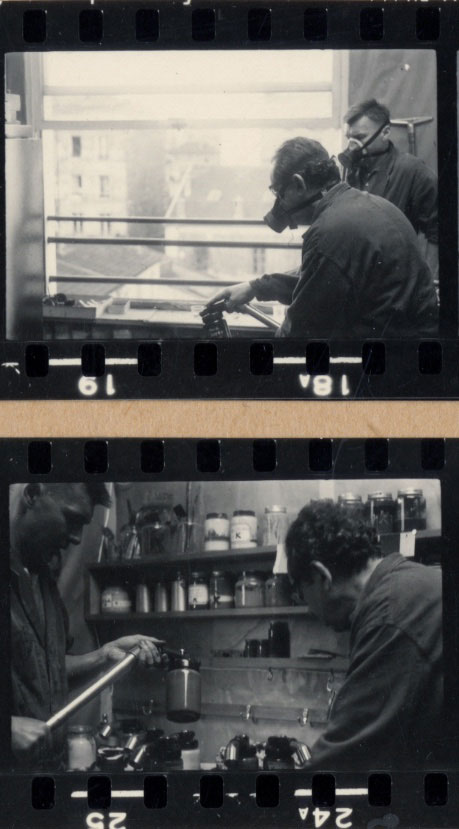

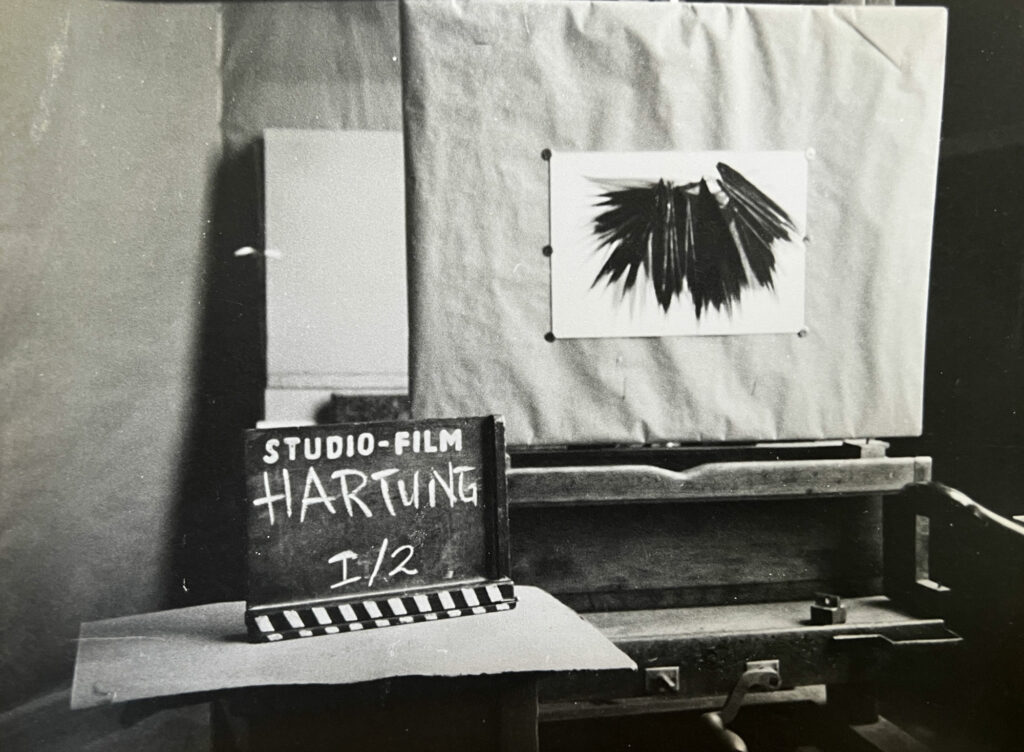

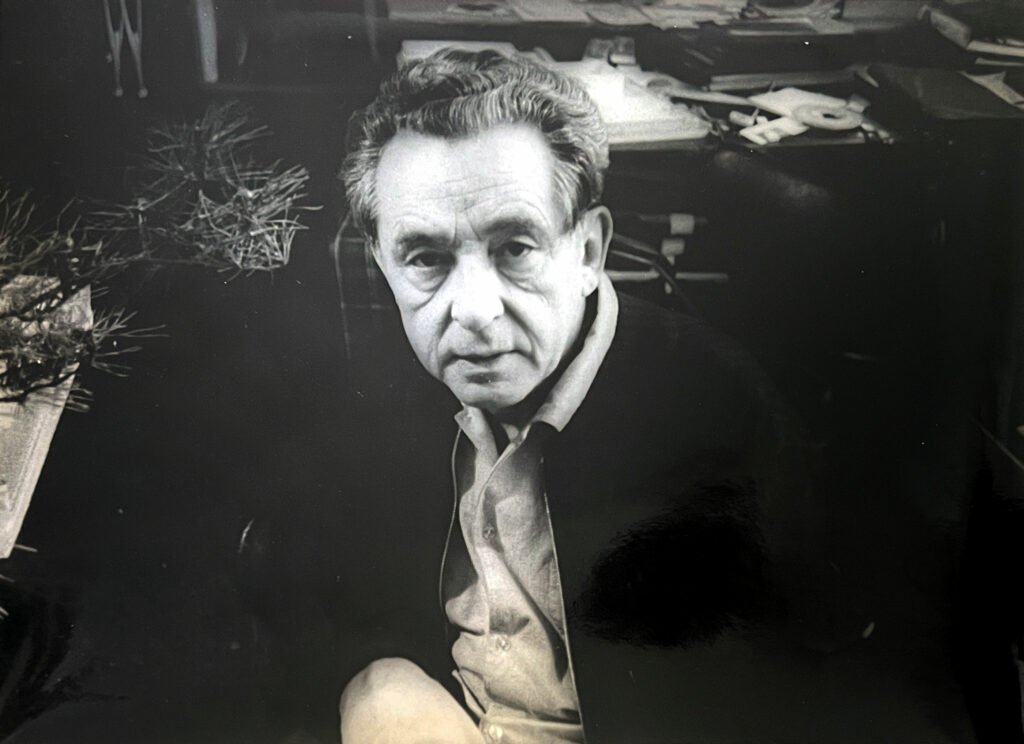

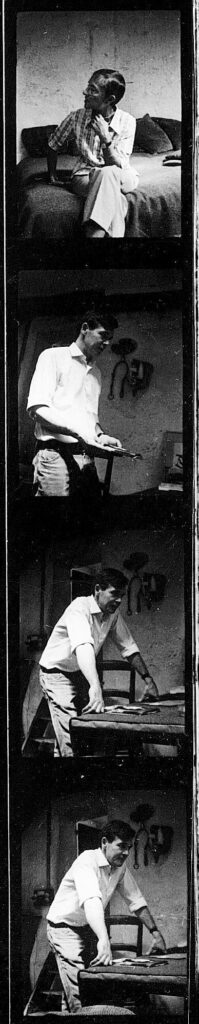

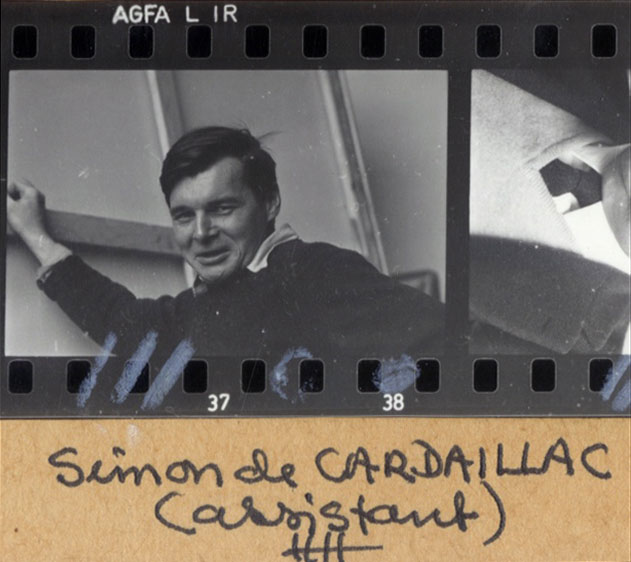

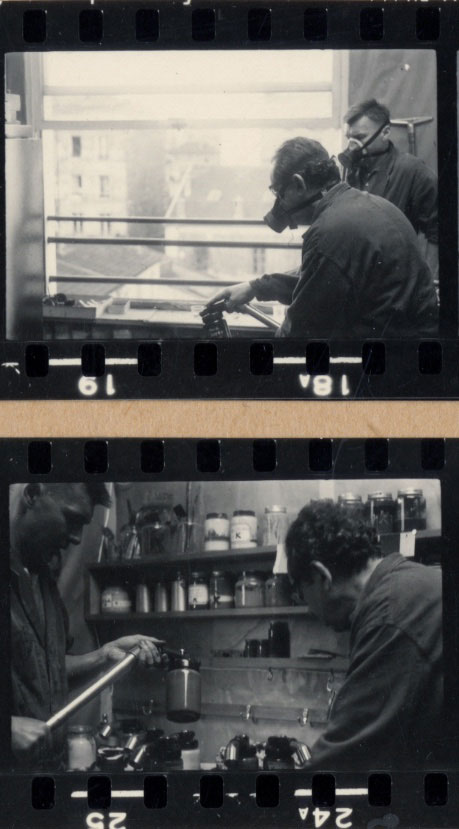

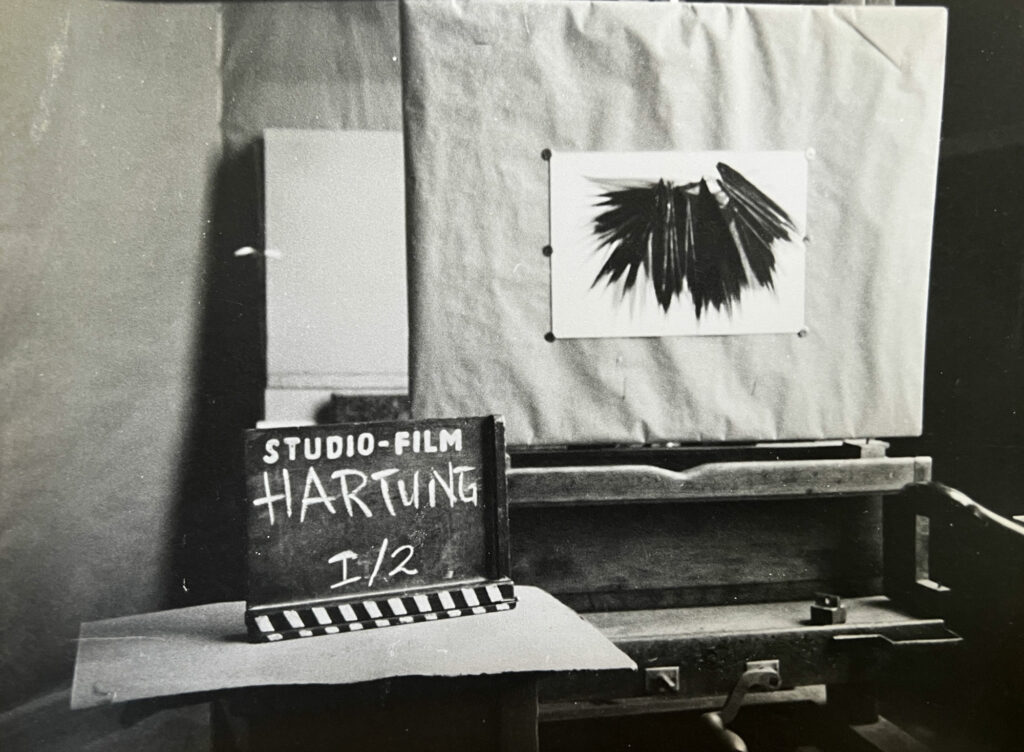

En 1966 et alors que les galeries et collectionneurs américains commençaient à s’interesser à sa peinture, Simon de Cardaillac, après deux ans de pause, décide de retourner travailler avec Hans Hartung. Entre 1961 et 1964, Simon avait en effet déjà été l’assistant de Hans Hartung. Il l’avait certainement rencontré lors du 11ème Salon des Réalités Nouvelles de 1956[1], sur lequel ils exposaient tous les deux. Entre 1961 et 1964, puis de 1966 à 1970, Simon de Cardaillac assiste donc Hartung dans la réalisation de ses oeuvres[2]. Tout laisse penser qu’il fut également l’assistant d’Anna-Eva Bergman. Comme nous le rappelle l’expert de Hans Hartung et d’Anna-Eva Bergman, Hervé Coste de Champeron, “dans de nombreux documents ou interviews, les assistants des différentes périodes parlent surtout de leur collaboration avec Hans Hartung car ils étaient uniquement questionnés sur ce point mais ils assistaient aussi Anna-Eva Bergman qui avait une production plus réduite mais pas moins exigeante techniquement.[3]”

[1] 11e Salon des Réalités Nouvelles Nouvelles Réalités, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, du 29 juin au 5 août 1956.

[2] Rainer Michael Mason, Hans Hartung, Catalogue raisonné des estampes, p.531

[3] Courriel du 18/12/2023

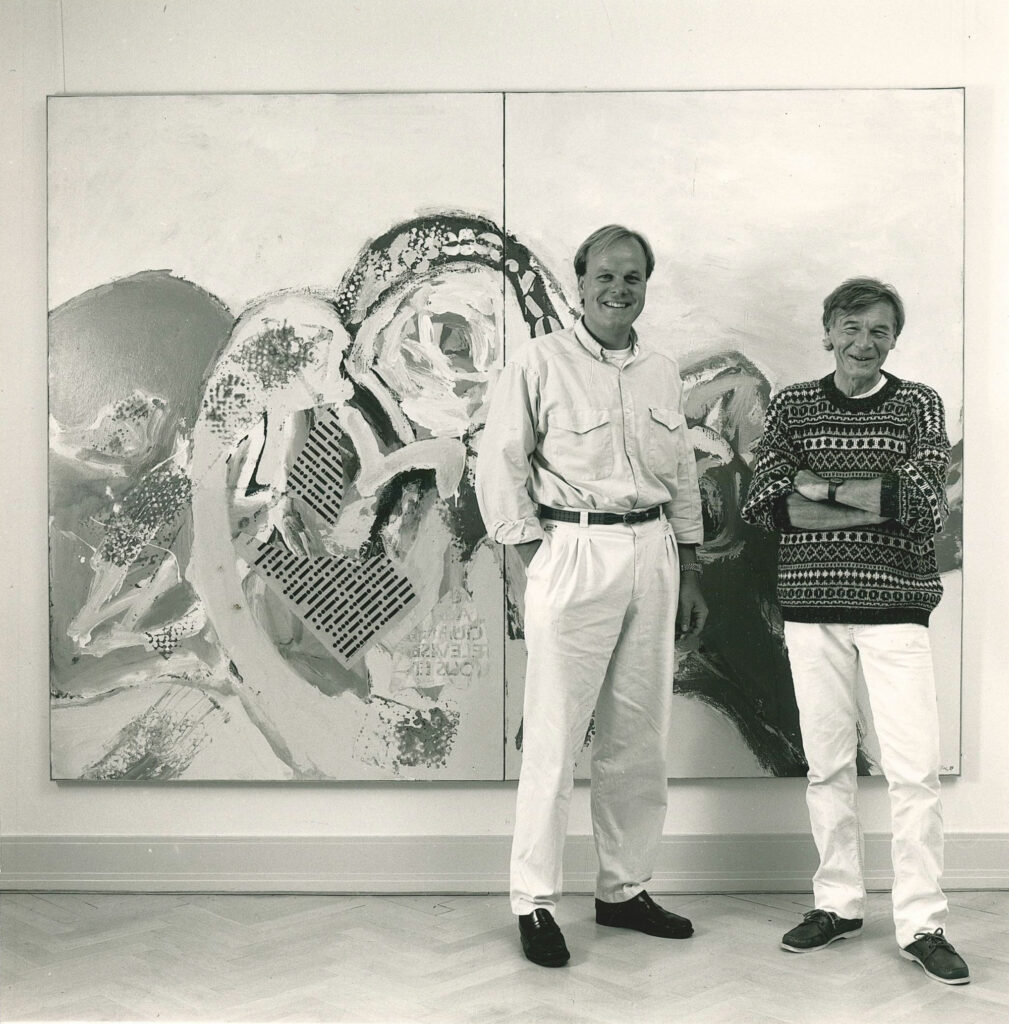

Ayant été formé à l’architecture aux Arts Décoratifs de Nice, Simon de Cardaillac aide notamment Hans Hartung à réaliser les plans de la construction du Champ des Oliviers (la maison atelier de Hans Hartung et d’Anna-Eva Bergman)[1]. A la fin de cette collaboration, en 1971, il reste en bon contact avec Hartung et Bergman – en témoignent un certain nombre d’archives dont de nombreuses lettres, cartes de vœux et invitations, donnant l’occasion à Hans Hartung et Anna-Eva Bergman de reformuler leur amitié pour Simon de Cardaillac. En 1977, alors qu’il ne travaillait plus pour eux depuis six ans, il intervint à nouveau dans la conception du portfolio La Foudre pilote l’Univers, composé de trois zincographies, en fournissant, à l’occasion, à Hartung son exemplaire de Héraclite d’Ephèse[2].

[1] Archives de la fondation Hans Hartung et Anna-Eva Bergman, courrier envoyé à Simon de Cardaillac le 23/10/2014

[2] Rainer Michael Mason, Hans Hartung, Catalogue raisonné des estampes, p.531

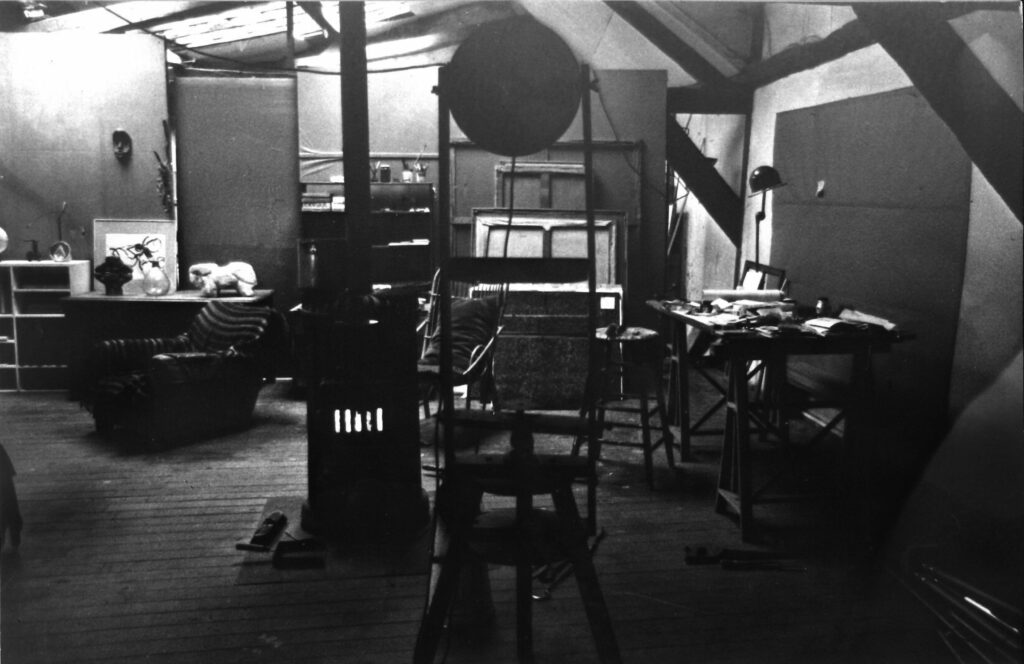

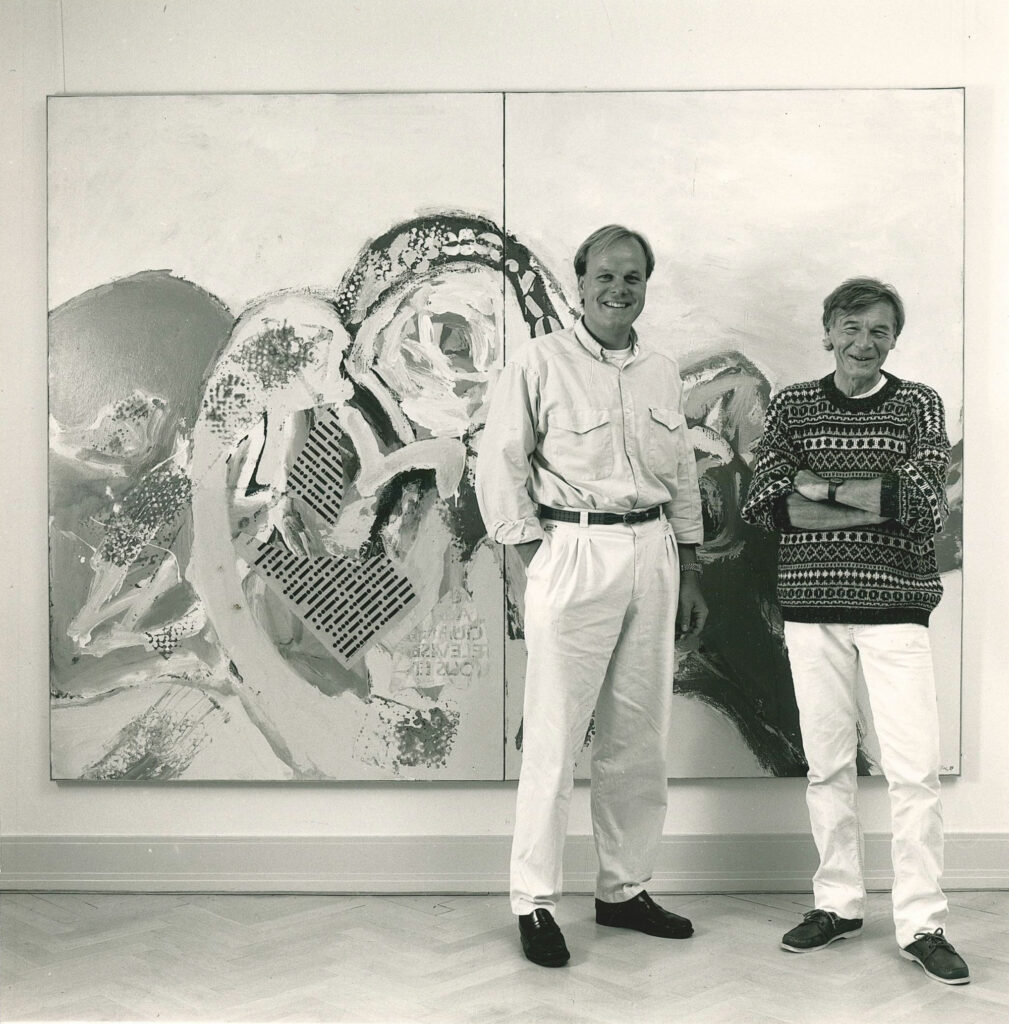

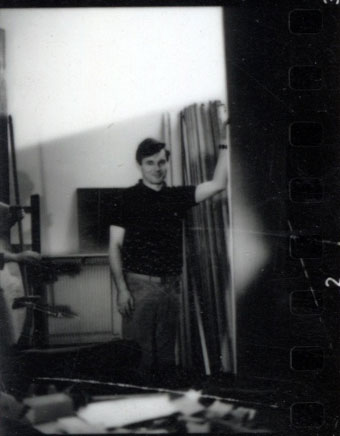

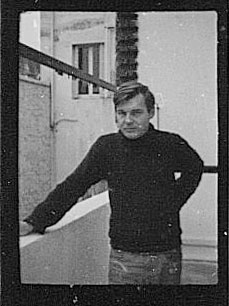

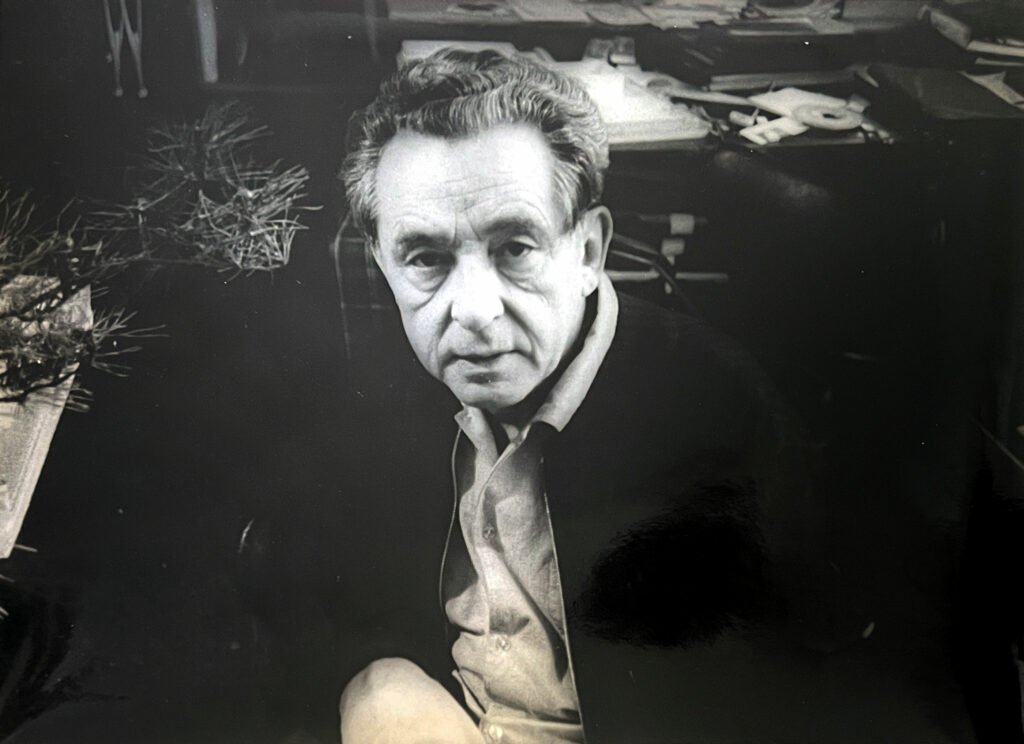

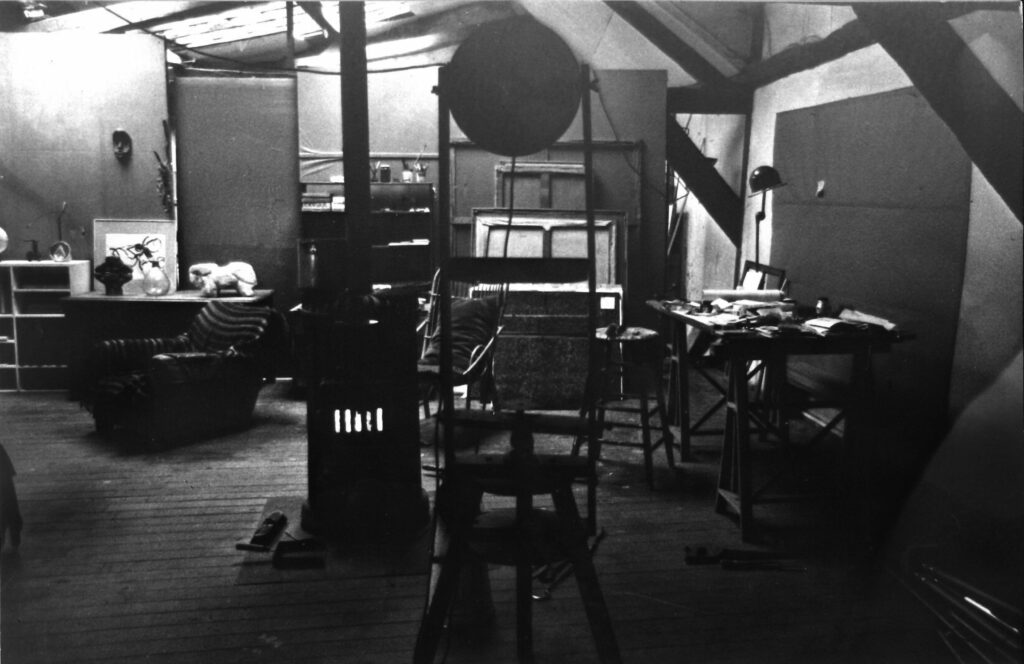

Outre les archives précédemment évoquées, nous conservons plusieurs documents attestant de la relation Cardaillac-Hartung-Bergman, dont plusieurs photos de Simon de Cardaillac dans leur atelier (archives Fondation Hartung Bergman). En témoignage de gratitude et signe d’amitié, Hans Hartung et Anna-Eva Bergman ont offert plusieurs œuvres à Simon de Cardaillac. Sur une photo de son atelier, on peut ainsi voir au mur une œuvre de Hans Hartung. Encore plus symbolique, Anna-Eva Bergman offrit à Simon de Cardaillac, au Noël 1963, le tableau N°56-1962 Petite image en carrés d’argent[3], dont la famille a confié la vente à Vichy Enchères.

[3] Archives de la fondation Hans Hartung et Anna-Eva Bergman

Malgré sa grande proximité avec le couple Hartung-Bergman, Simon de Cardaillac ne chercha jamais à se servir de cette relation ou de ses contacts pour se faire connaître et cette attitude le suivit toute sa vie.

“La pudeur de chacun et la discrétion de nos relations me laissent très libre dans mon propre travail. Il faut savoir ne pas mélanger les genres.”

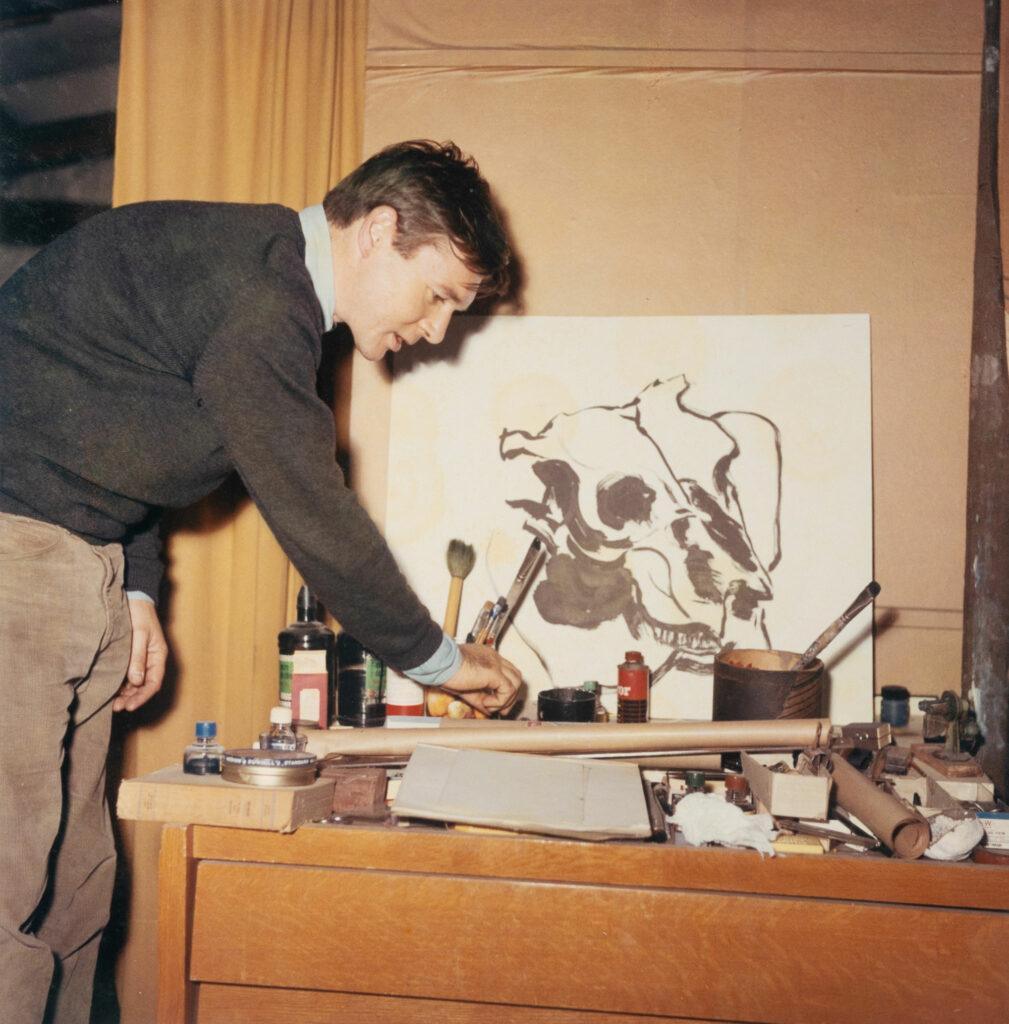

Simultanément à son travail avec Hans Hartung et Anna-Eva Bergman, Simon de Cardaillac a le temps de se consacrer à sa peinture dans un grand atelier à Sèvres, situé au-dessus de chez Antoine Tudal. Il reçoit de nombreuses visites, dont celles d’Anne de Staël, fille unique de Nicolas de Staël et de Jeannine Guillou, avec laquelle il est très ami.

“On se retrouvait dans le grand atelier où vivaient Simon, Nicole et leurs enfants. C’était un grand atelier de peintures qui était absolument magnifique. Parfois, je venais le soir, ils m’offraient de dîner avec eux. Tout en dînant, Simon retournait très vite à ses tableaux. On parlait peinture, de la vie, il était très cultivé, extrêmement cultivé. Nos sujets de conversation étaient infinis, toujours très intelligents.

Son atelier était éminemment chaleureux : il était idéalement chaleureux. Plein d’âme. Il avait de grands volumes, remplis de tableaux commencés, pas finis.

Simon ne ressemblait pas du tout à mon frère Antek. Il apportait autre chose. C’était quelqu’un de très subtil et passionnant. Je m’entendais bien avec sa pensée. C’était son souci sa peinture. Mais on ne parlait pas seulement de peinture. On parlait de tout. C’était un esprit très cultivé. Ce qui me touchait, c’est qu’il pouvait lire des livres qui me passionnaient… Nous aimions particulièrement la philosophie, Nietzsche, la poésie.

Entretien avec Anne de Staël, le 11 décembre 2023

A cette époque, Simon de Cardaillac et Anne de Staël s’écrivaient souvent. Nous conservons des lettres d’Anne teintées de poésie, qui laissent transparaître son admiration pour Simon.

“ Pour moi l’autre jour c’était une joie d’être venue te voir, de voir que tu étais toujours “le même”. Cette fidélité à laquelle nous tenons tellement est le plus rare quand elle vous est donnée – c’est celle envers soi. […] J’ai vu Antek qui avance avec l’image figée sur son visage de l’enfant prodige un peu jaunie et la peur de vieillir ! Parce que, lui, c’est l’inverse, il est celui qu’on regarde.

Alors que toi tu es celui qui regarde. L’observateur, qui sait élever une conversation enjouée avec le silence des choses et les choses le lui rendent bien à travers les êtres! Est-ce que quelque chose est donné par le silence des couleurs, au peintre !? Je veux dire que celui qui regarde fait très attention d’avancer ni plus vite ni plus lentement et par là il ne vieillit pas, le temps lui réserve son jour frais ! ”

Lettre d’Anne de Staël à Simon de Cardaillac, 13/02/1997

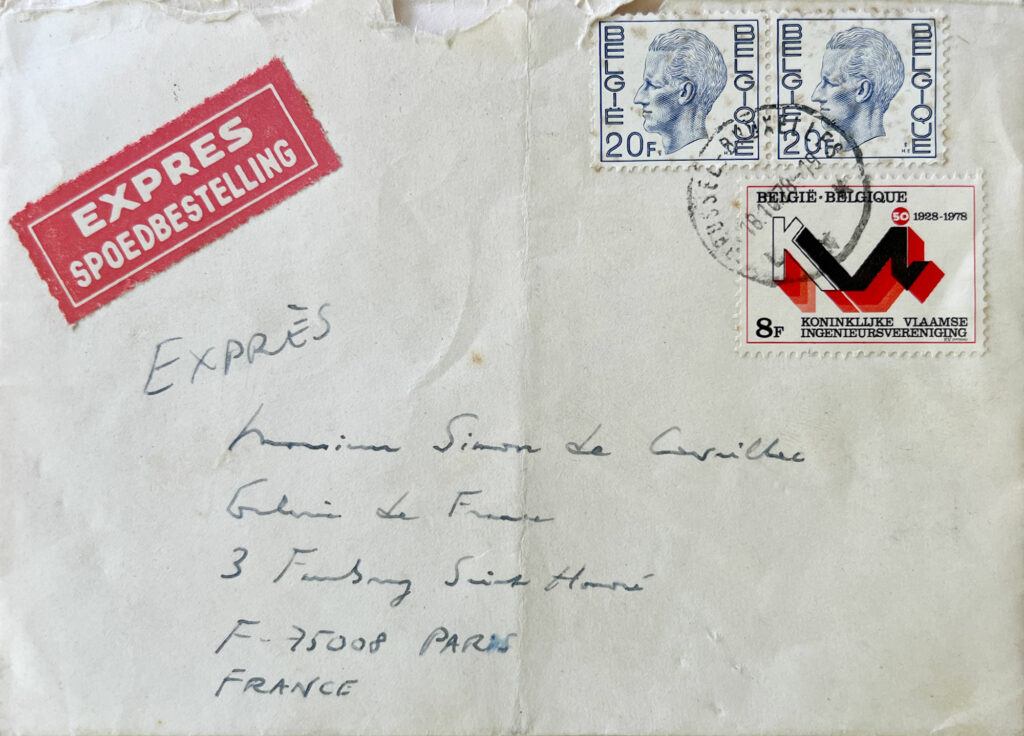

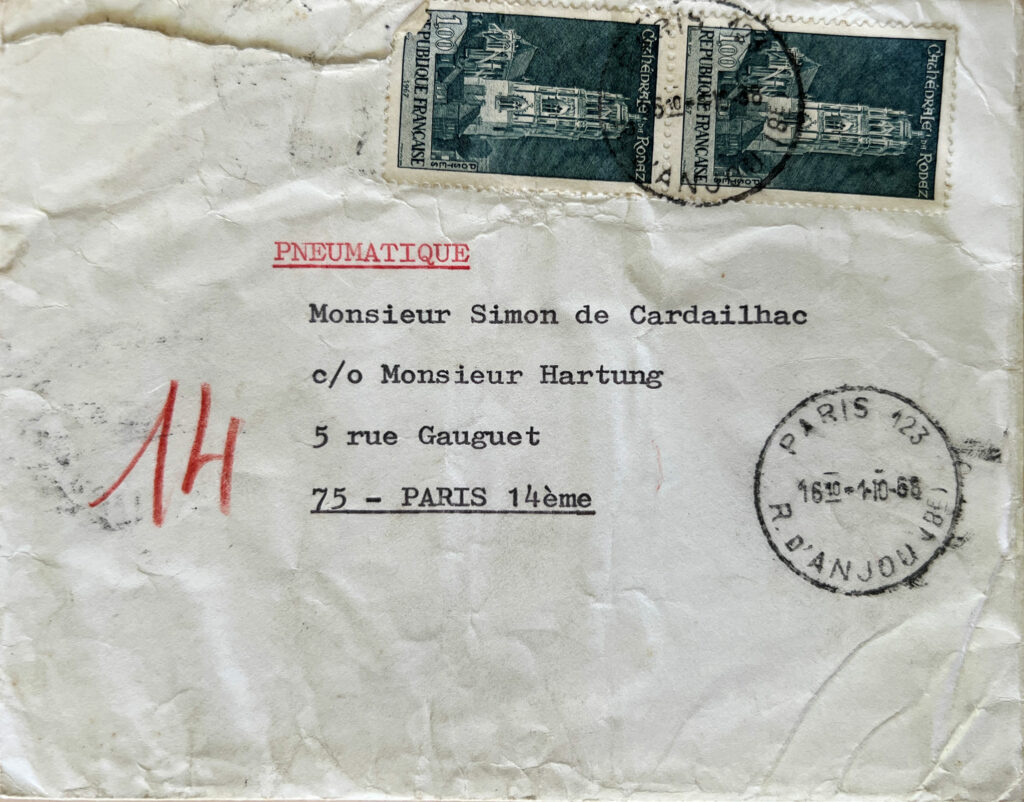

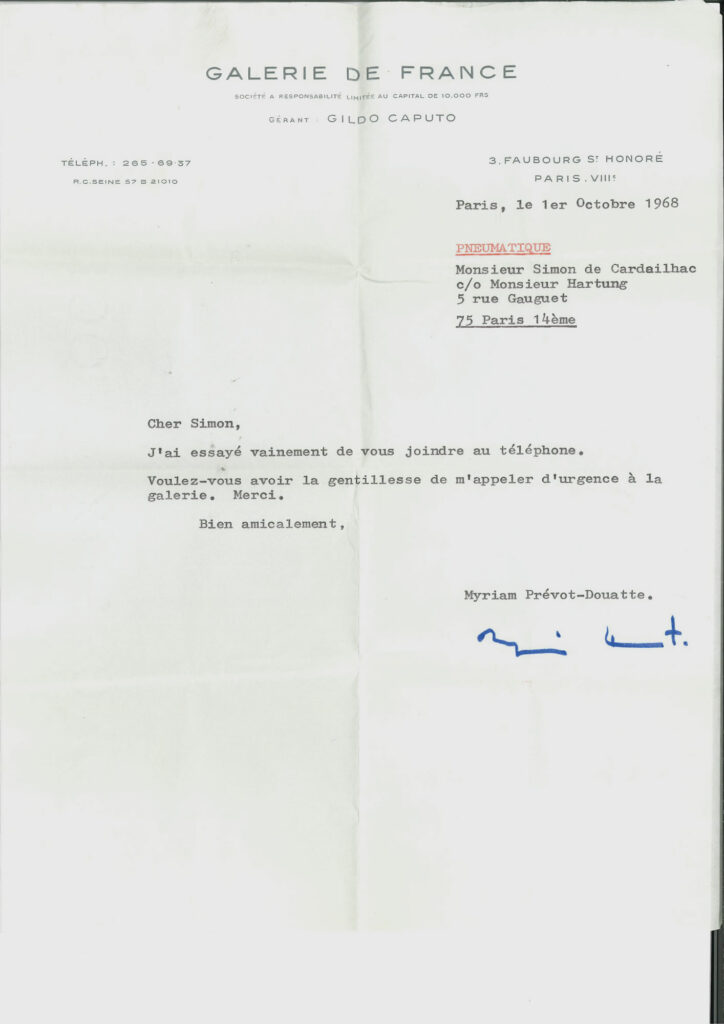

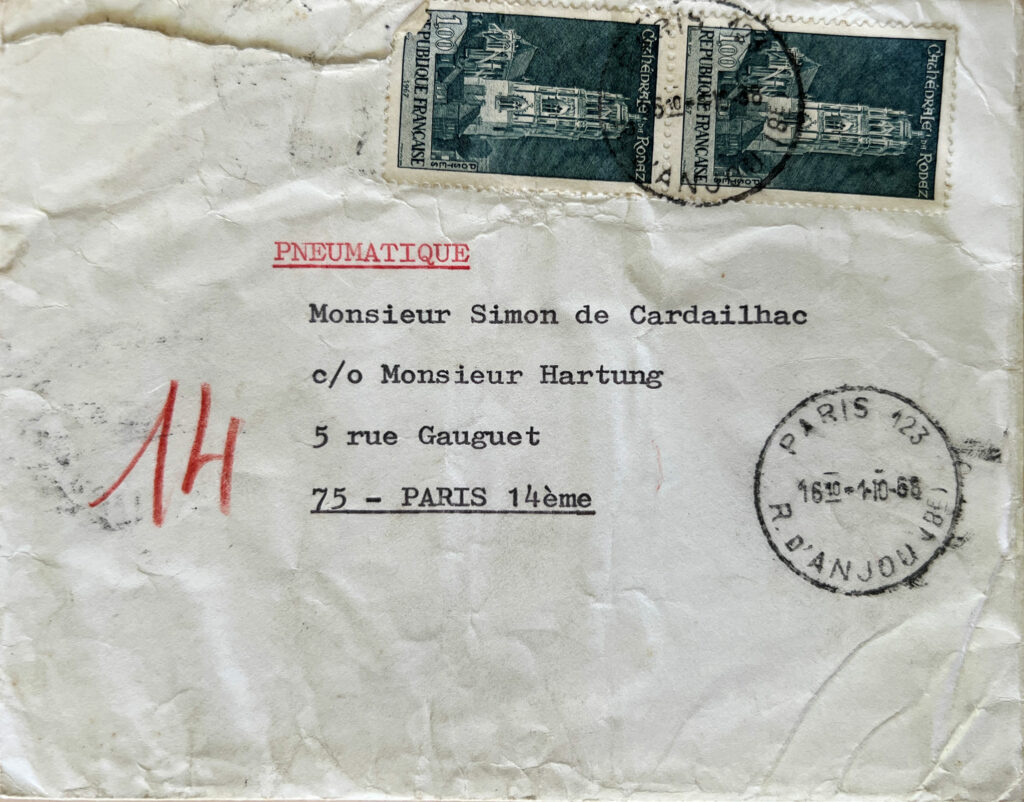

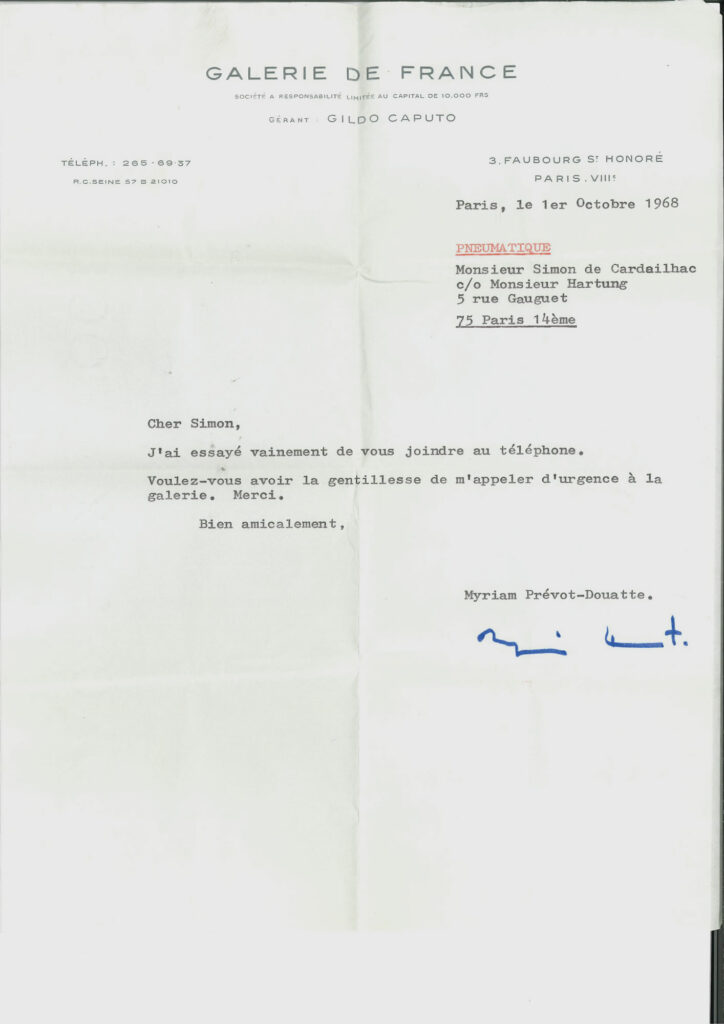

En 1971, Myriam Prévot, directrice de la Galerie de France, propose à Simon de Cardaillac de travailler pour elle. Commence dès lors une collaboration intéressante pour Simon qui conçoit ce nouveau poste comme un “terrain d’observation” du “monde du marché de l’art” et une opportunité pour le temps qu’il lui libère pour se consacrer à sa peinture.

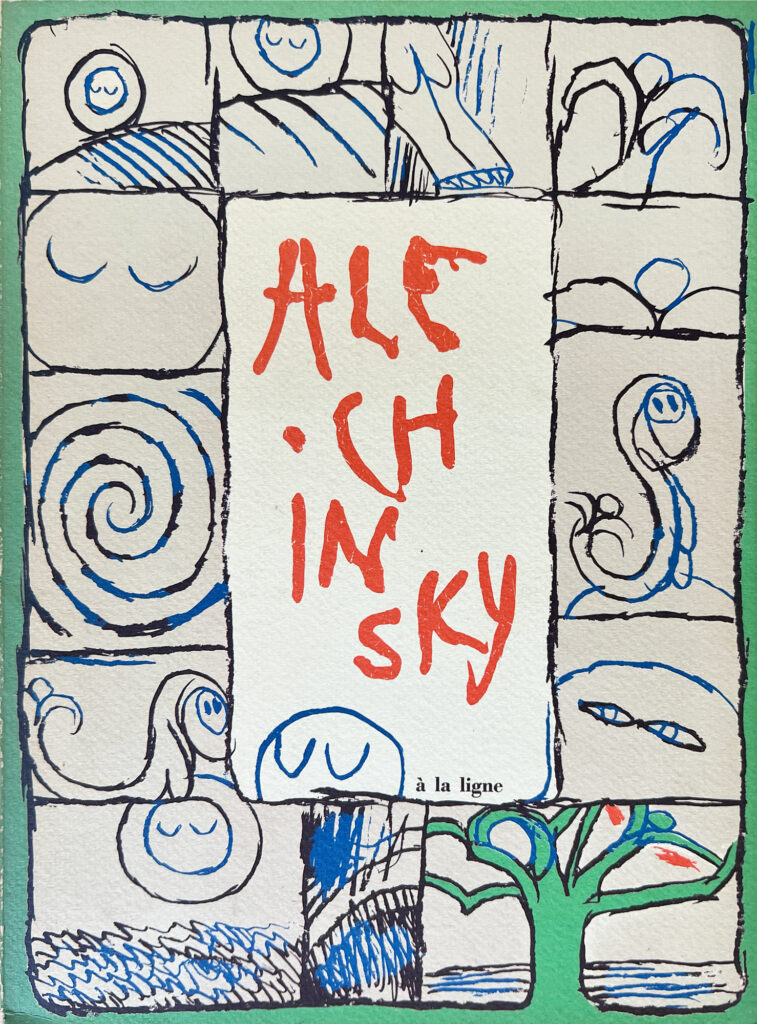

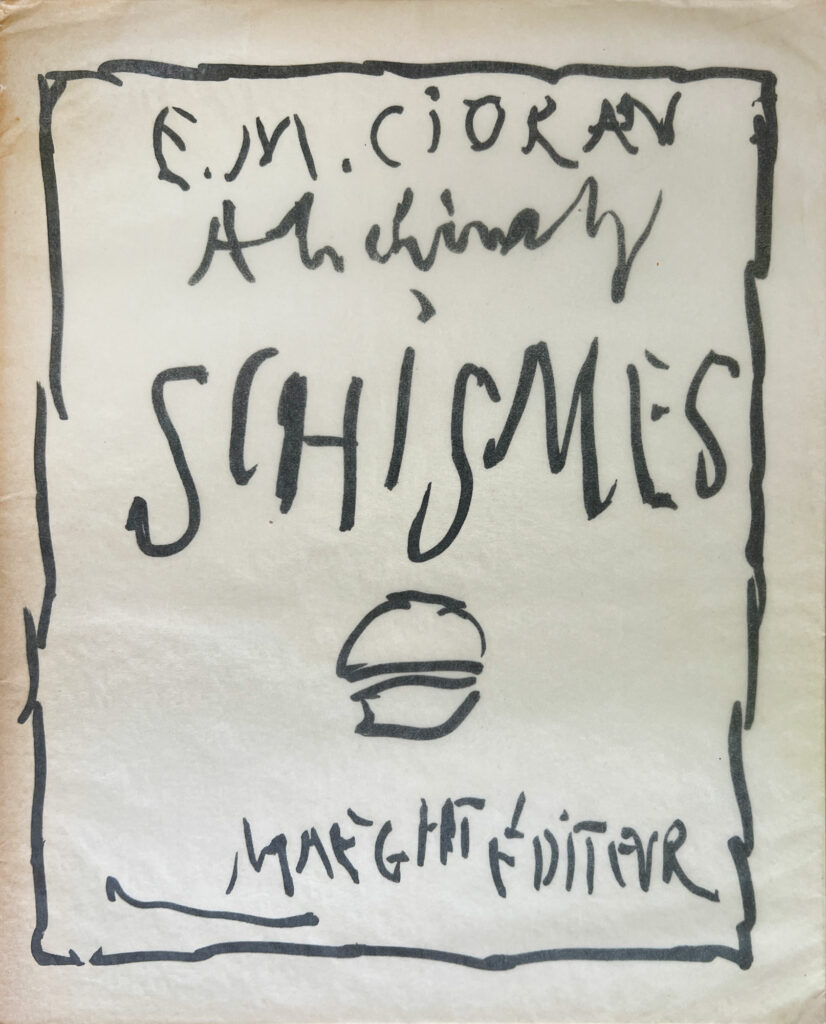

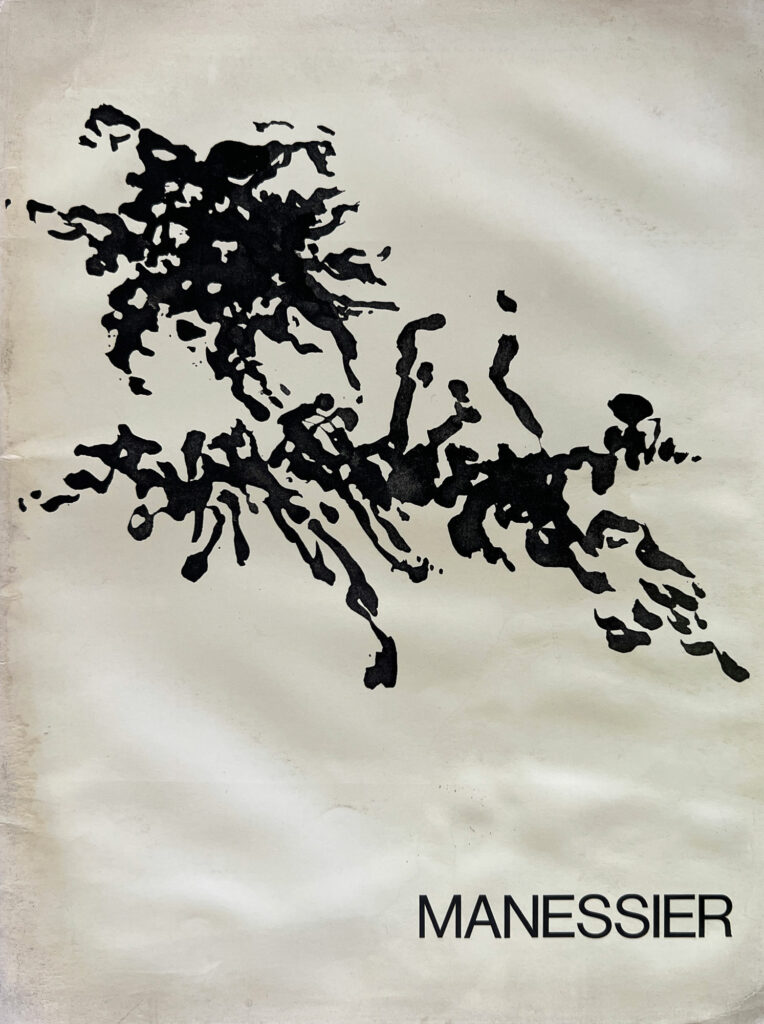

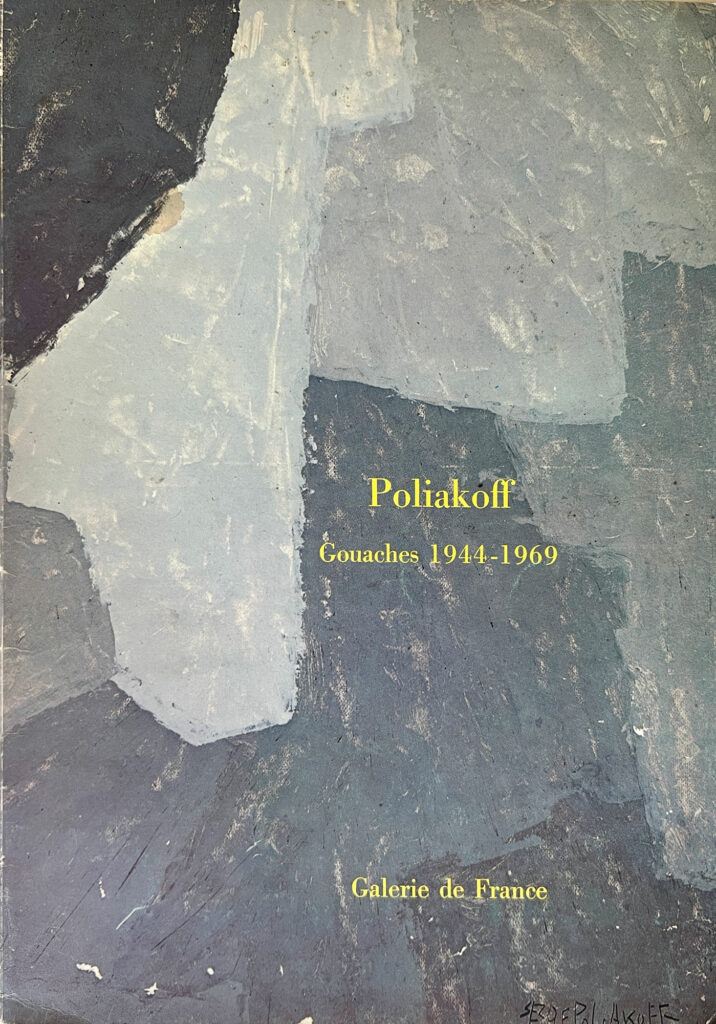

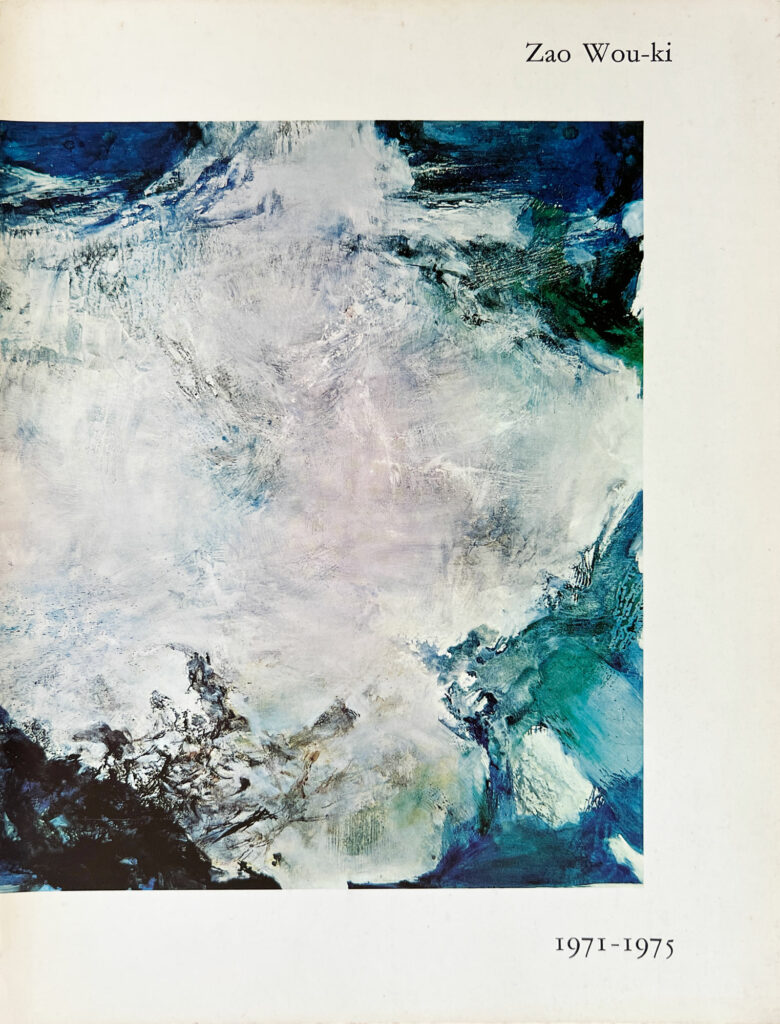

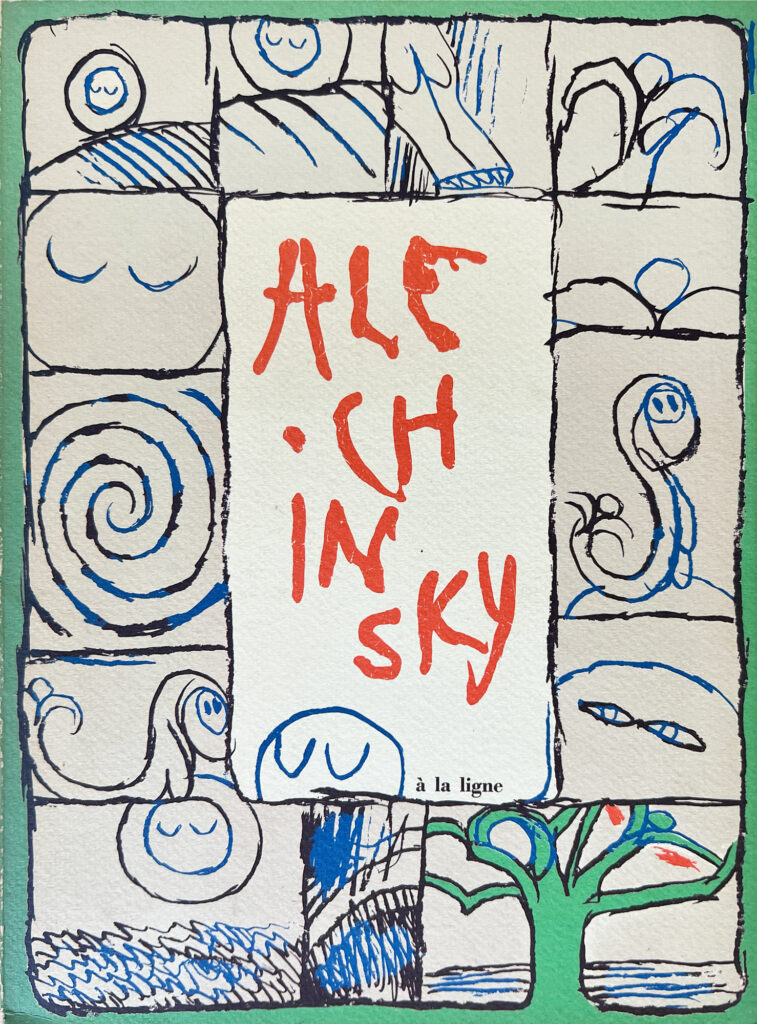

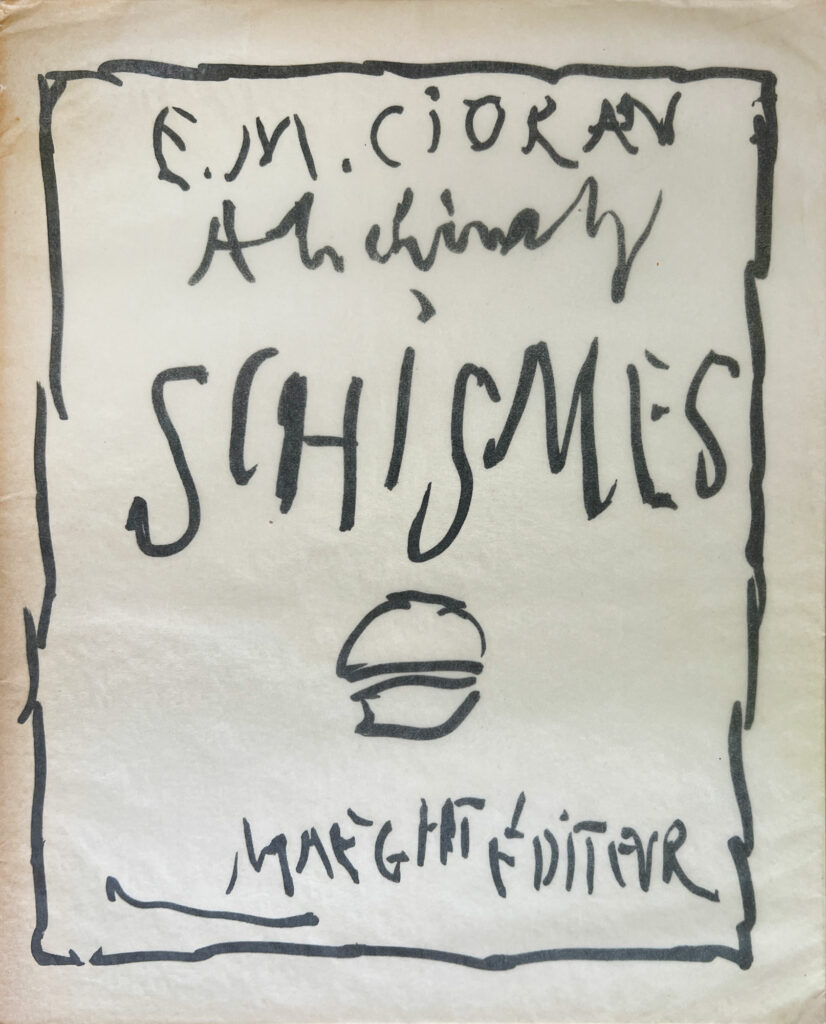

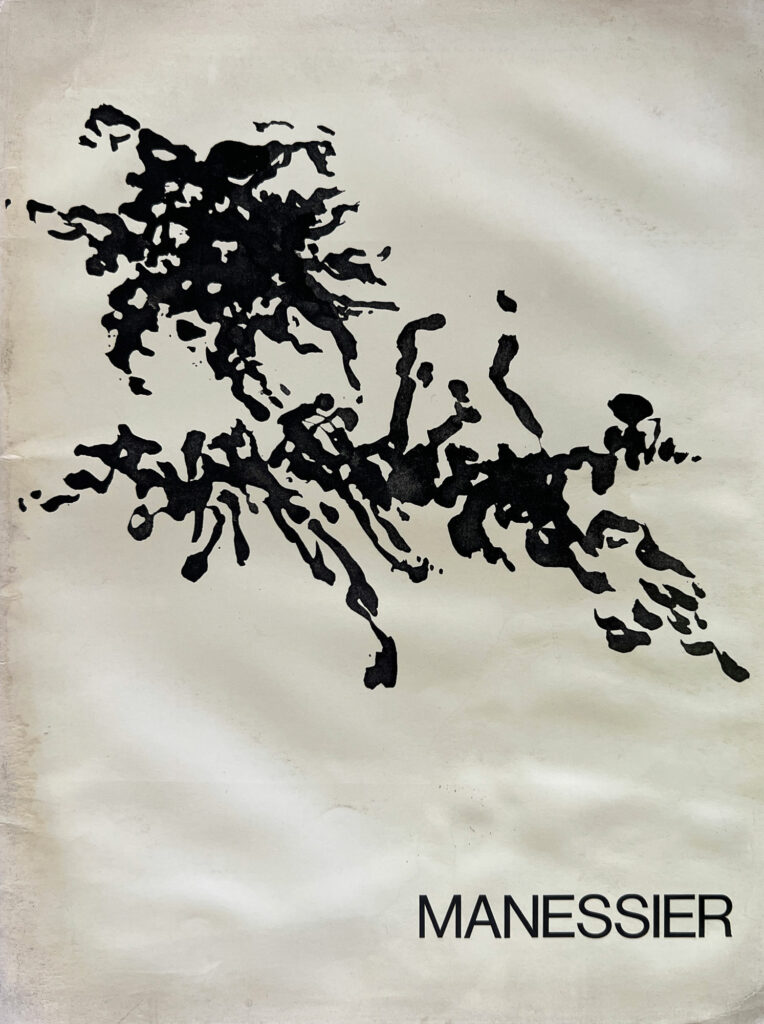

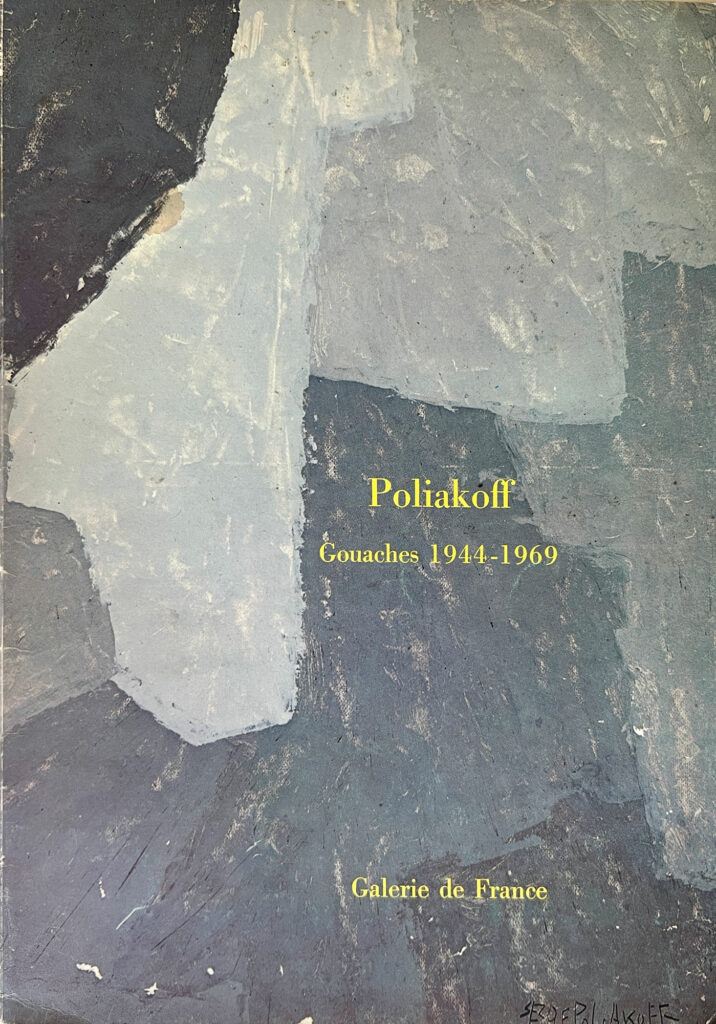

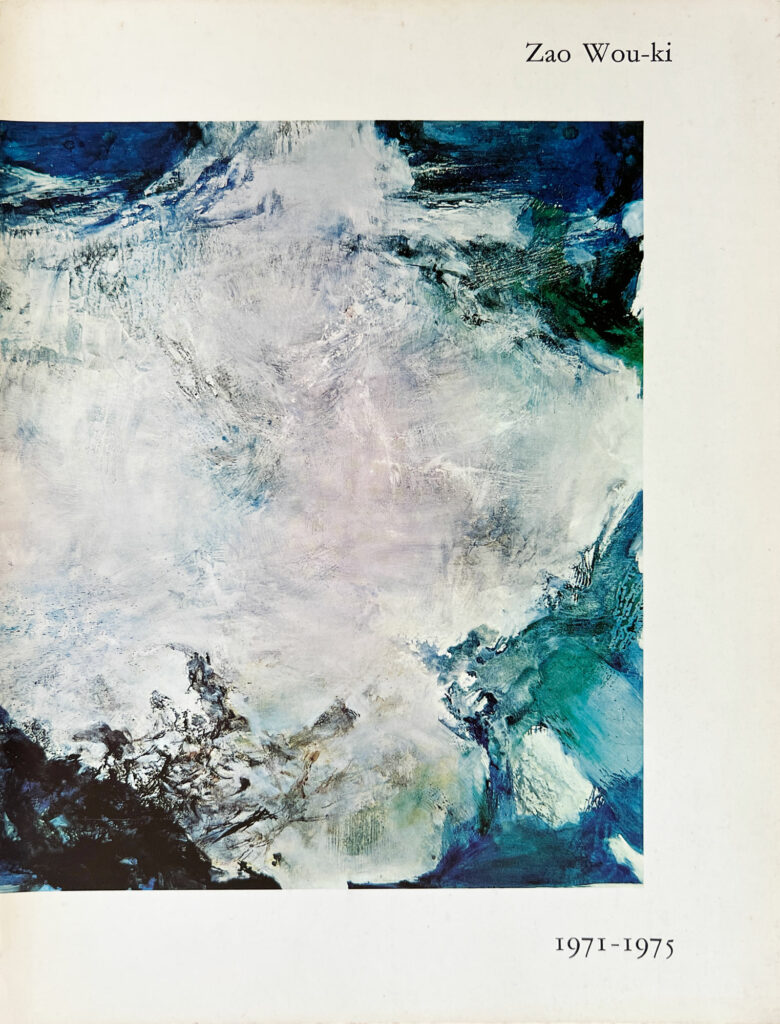

Entre 1971 et 1978, il participe pleinement à l’organisation d’un grand nombre d’expositions d’artistes emblématiques de son temps, tels que Pierre Alechinsky (1971, 1973, 1977, 1978), Anna-Eva Bergman (1977), Christian Dotremont (1971, 1975, 1978), Hans Hartung (1971, 1974, 1977, 1979), Alfred Manessier (1975, 1978), Pierre Soulages (1972, 1974, 1977) ou Zao Wou-Ki (1972, 1975).

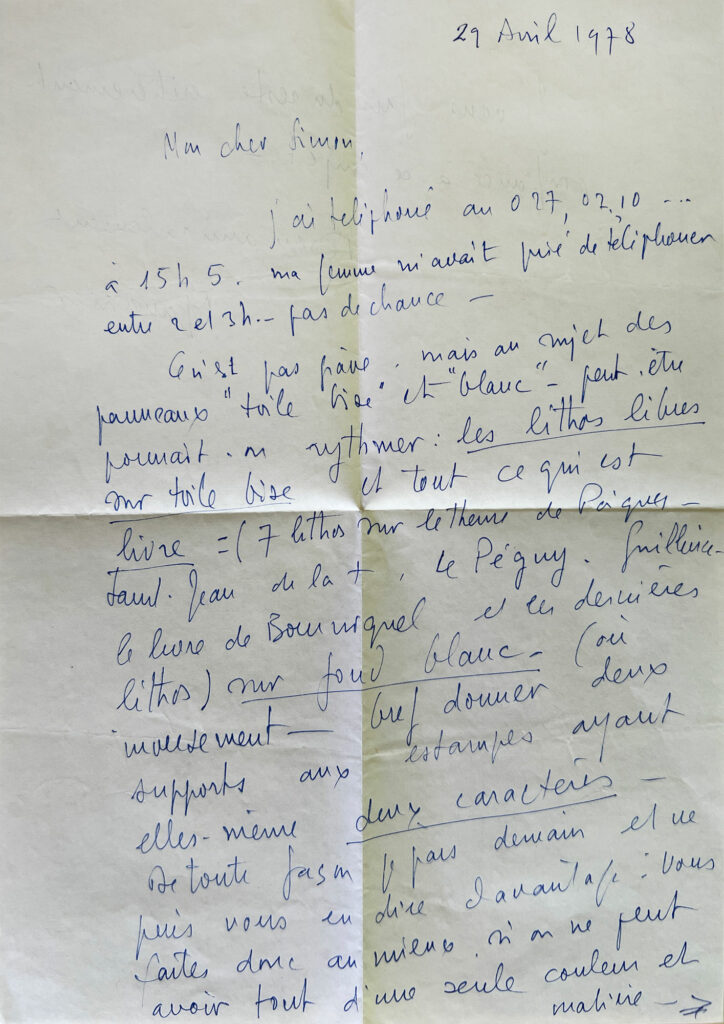

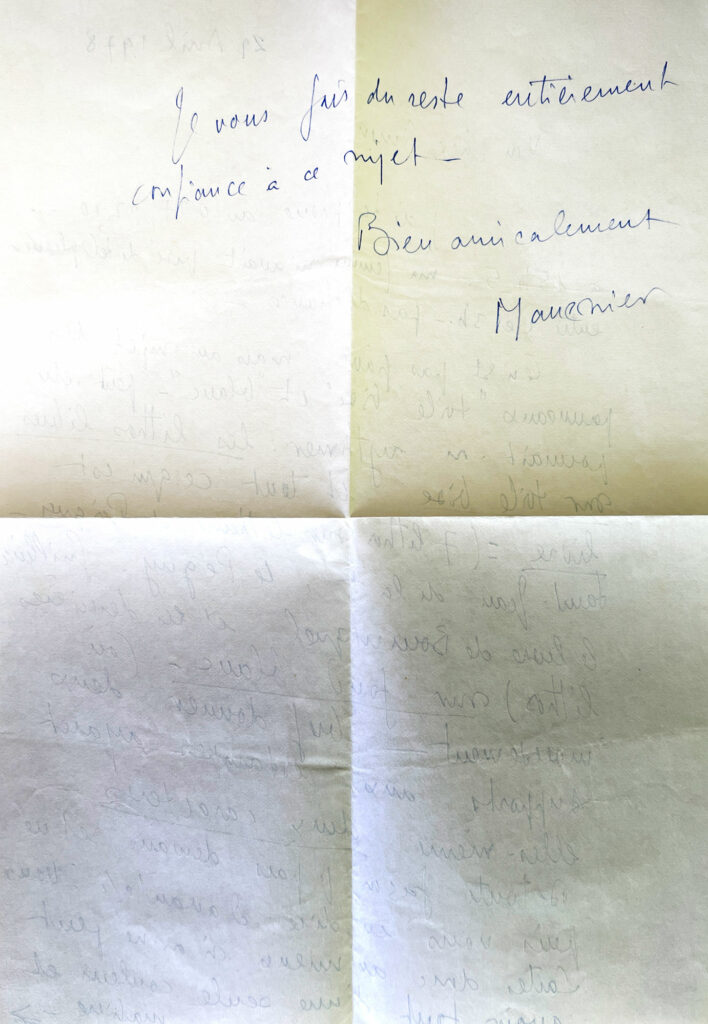

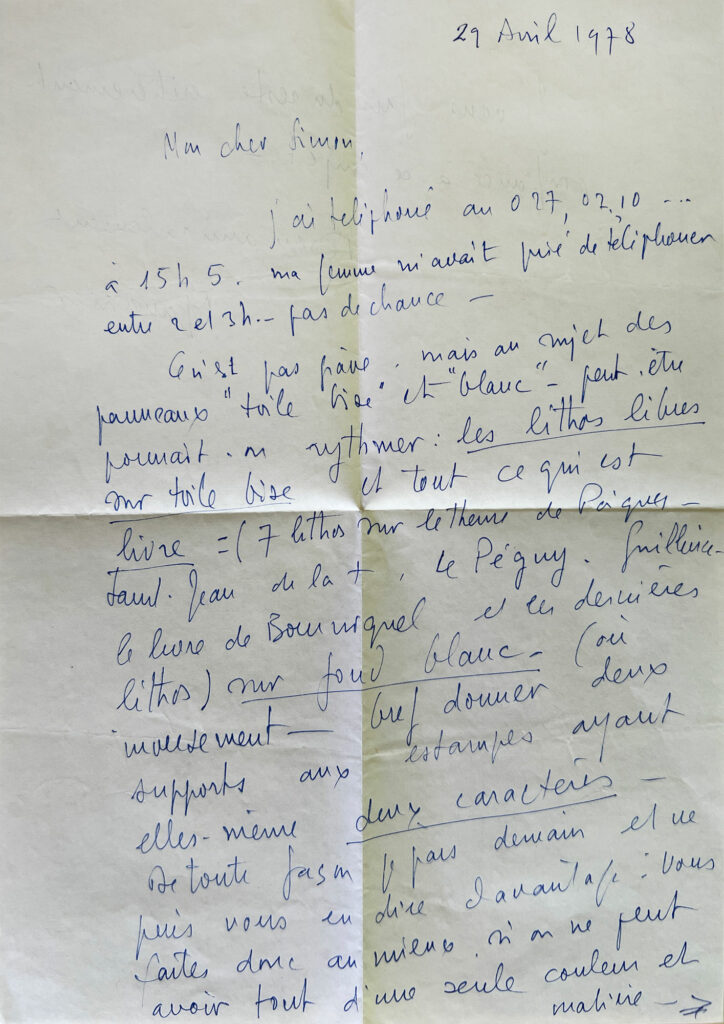

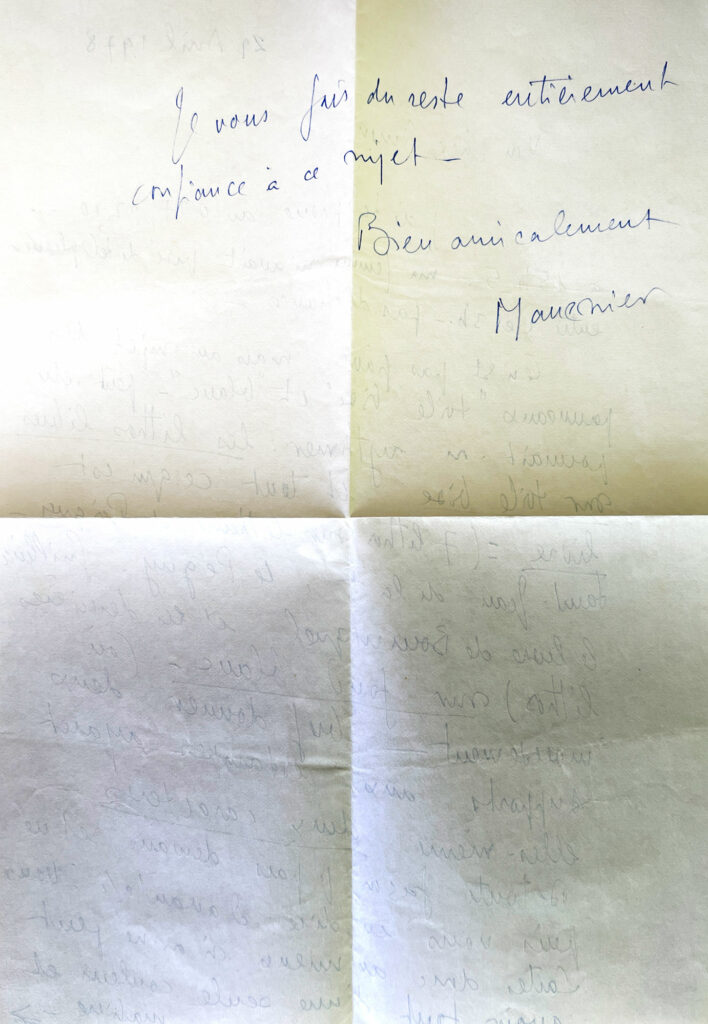

Plusieurs archives conservées par la famille viennent témoigner de cette activité, dont des lettres renseignant sur l’organisation des expositions, à l’instar de celle d’Alfred Manessier du 29 avril 1978 “Mon cher Simon, j’ai téléphoné […] au sujet des panneaux “toile grise” et “blanc” peut-être pourrait-on rythmer : les lithos livres sur toile grise et tout ce qui est livre […] De toute façon je pars demain et ne puis vous en dire davantage ; vous faites donc au mieux si on ne peut avoir tout d’une seule couleur et matière. Je vous fais du reste entièrement confiance à ce sujet. Bien amicalement, Manessier”

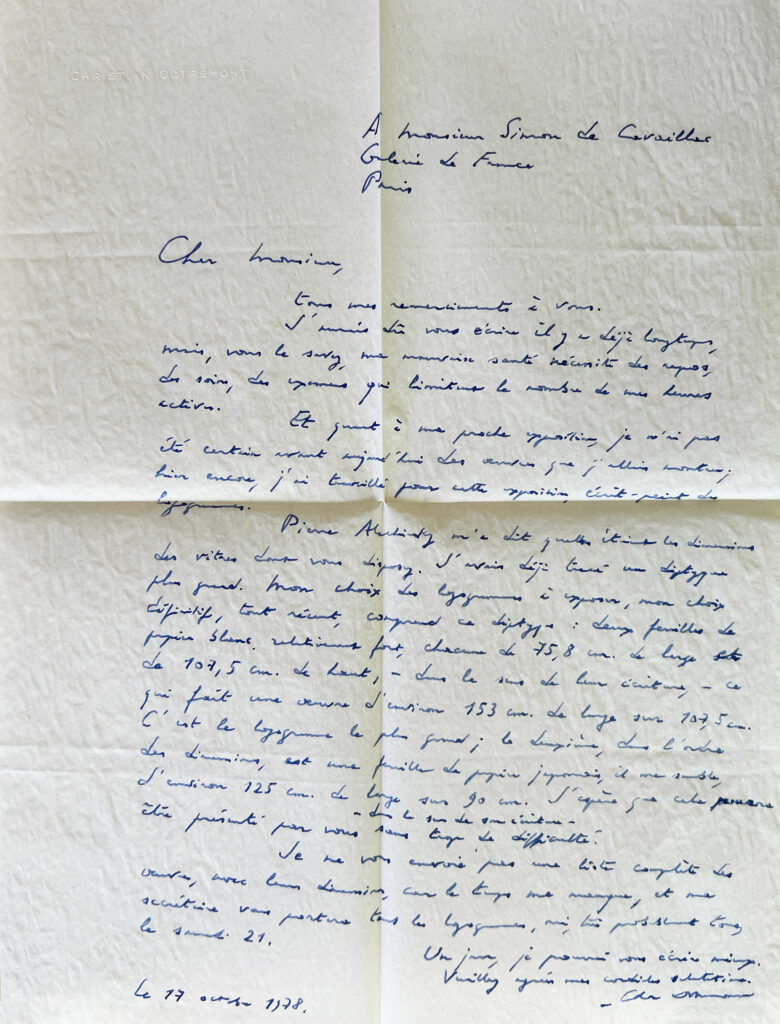

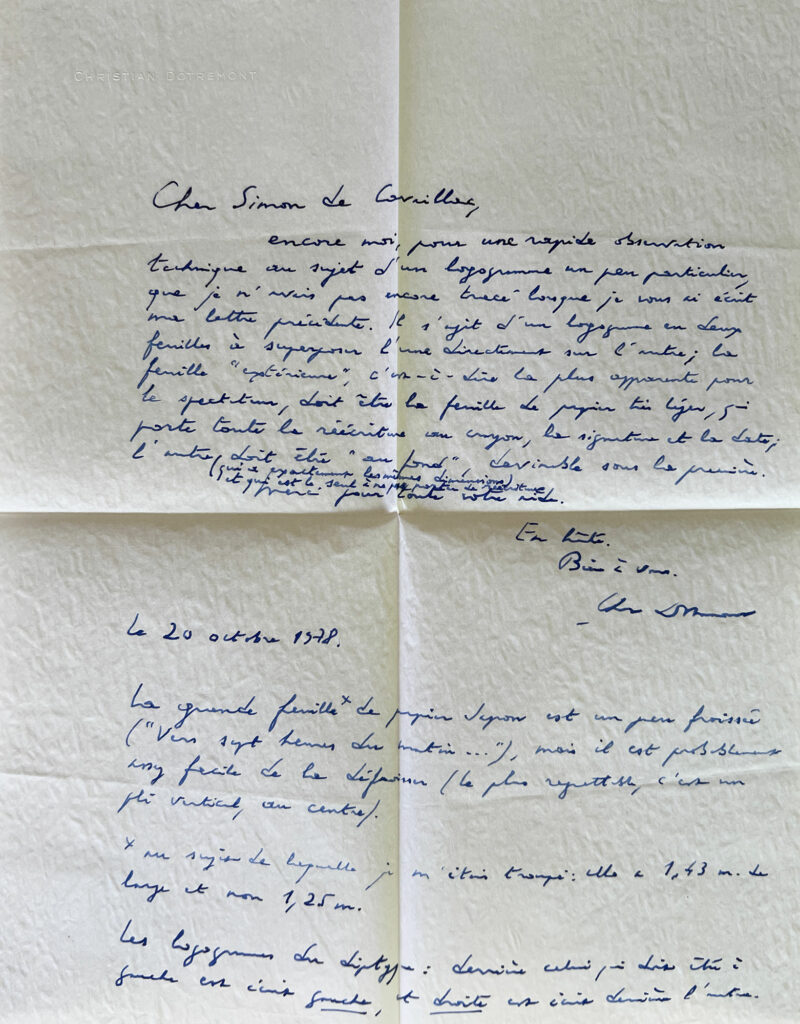

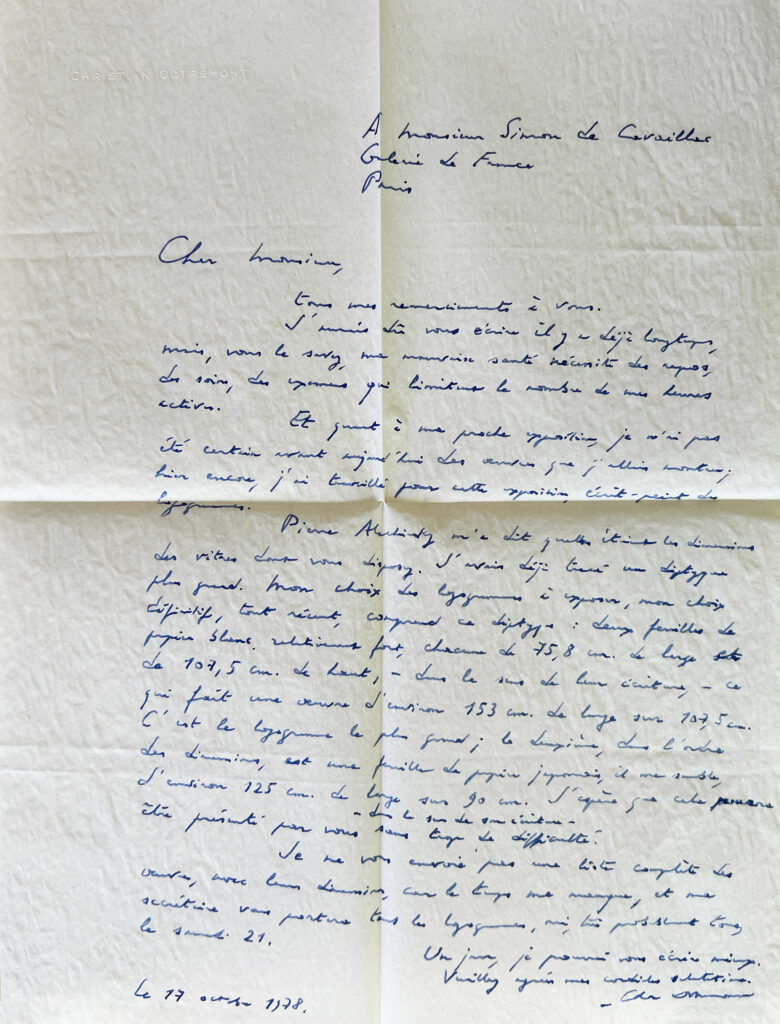

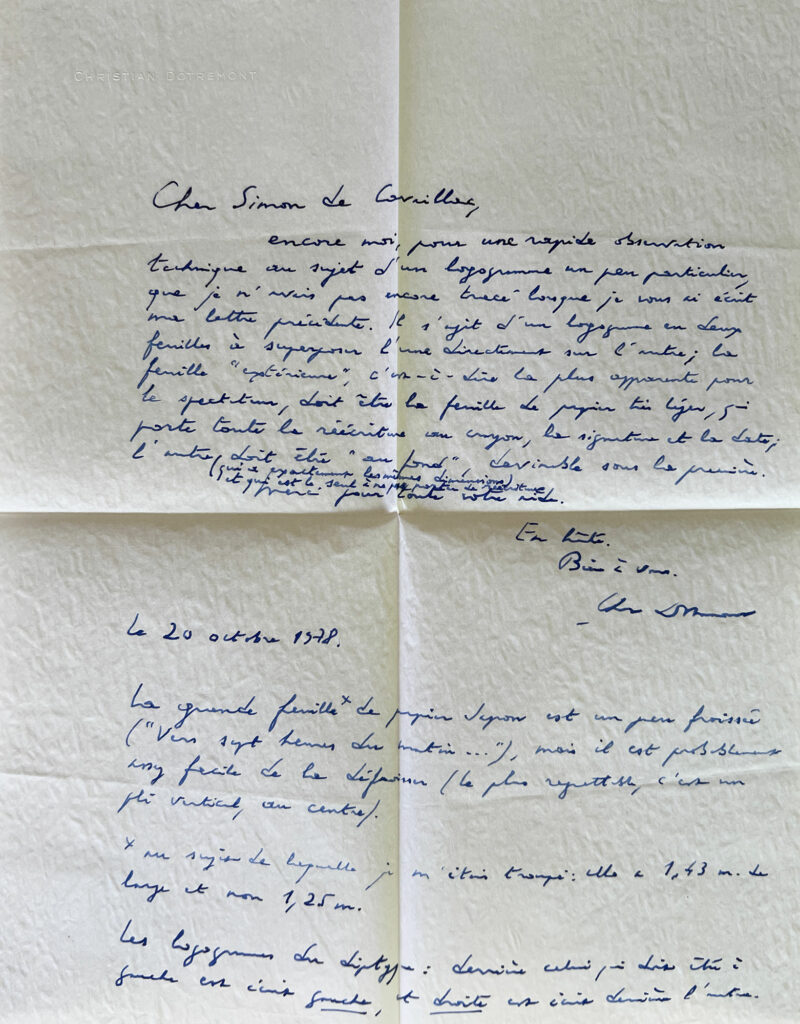

Le 17 octobre 1978, c’est Christian Dotremont qui écrit à Simon de Cardaillac :

“ Et quant à ma proche exposition, je n’ai pas été certain avant aujourd’hui des œuvres que j’allais montrer ; hier encore, j’ai travaillé pour cette exposition, écrit-peint des logogrammes.

Pierre Alechinsky m’a dit quelles étaient les dimensions des vitres dont vous disposez. J’avais déjà tracé un diptyque plus grand. Mon choix des logogrammes à exposer, mon choix définitif, tout récent, comprend ce diptyque. ”Christian Dotremont, lettre à Simon de Cardaillac, le 17 octobre 1978

Alfred Manessier, Christian Dotremont et Pierre Alechinsky avaient en effet exposé la même année 1978 à la Galerie de France. Simon de Cardaillac est devenu ami avec certains de ces artistes, dont Alechinsky. Il fut invité à plusieurs de ses vernissages et notamment à son exposition à la FIAC, au stand Maeght Lelong, à l’occasion de son anniversaire.

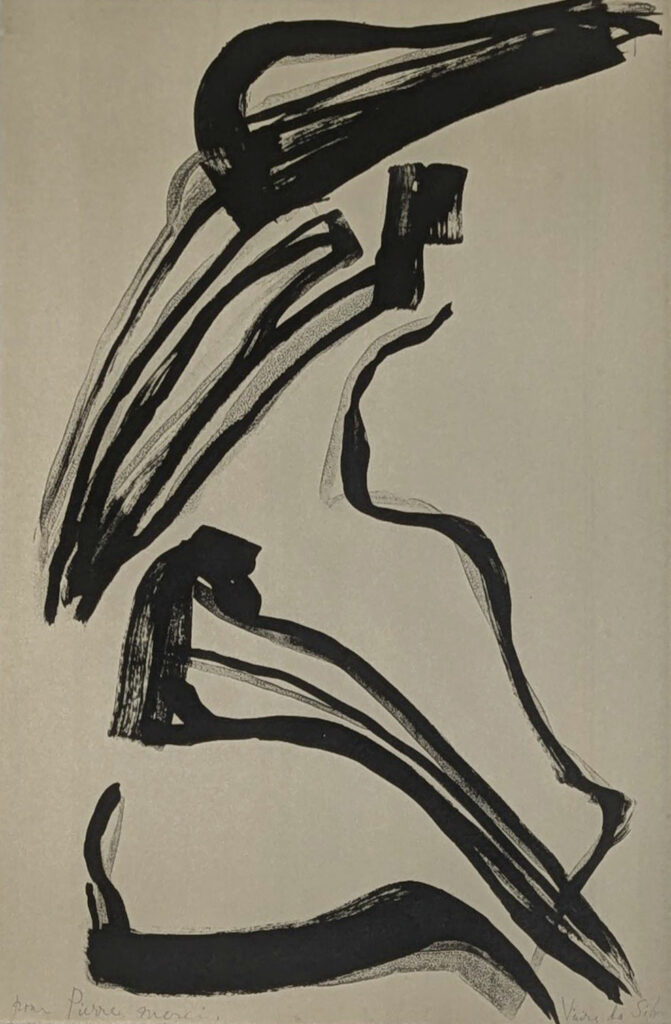

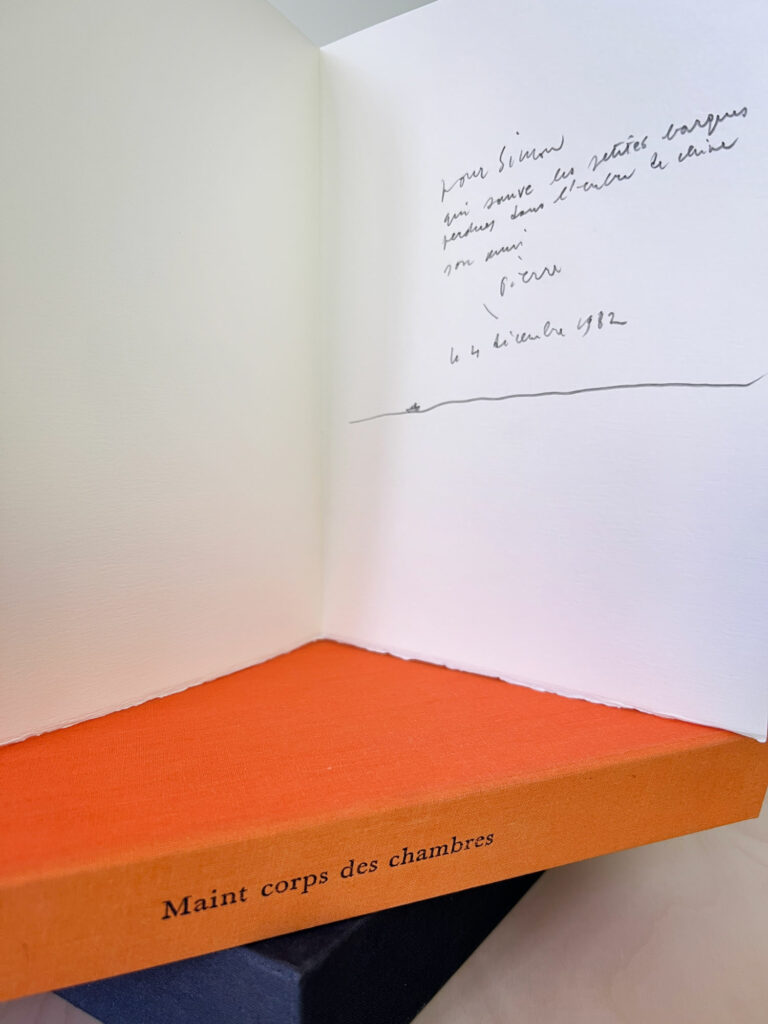

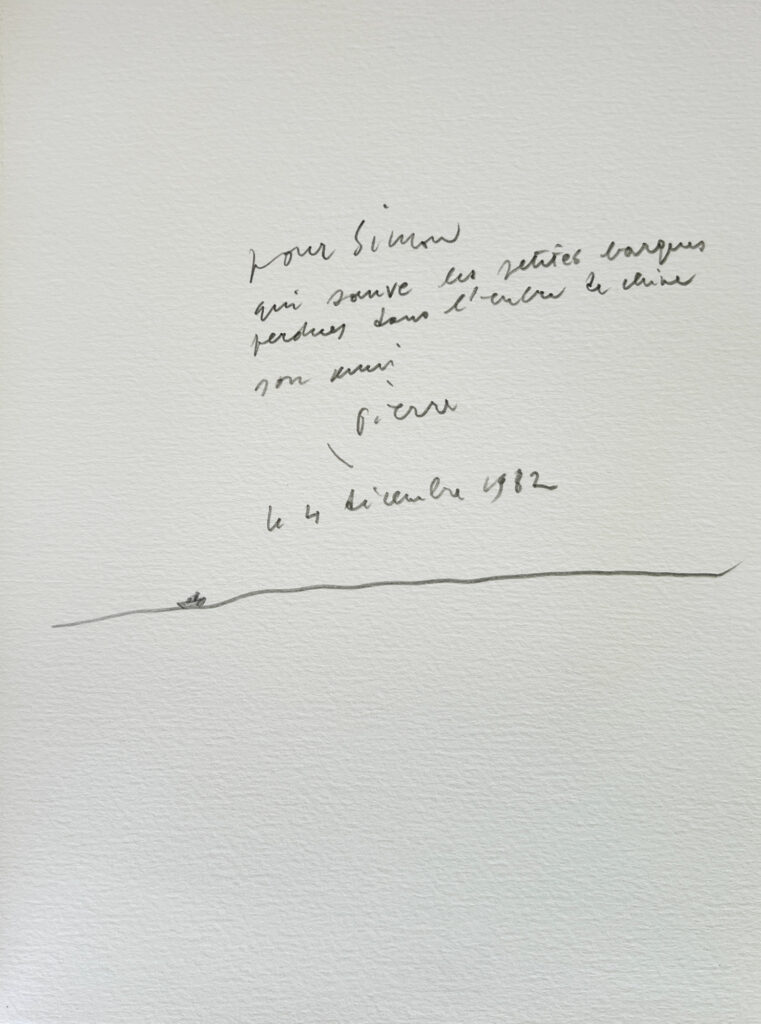

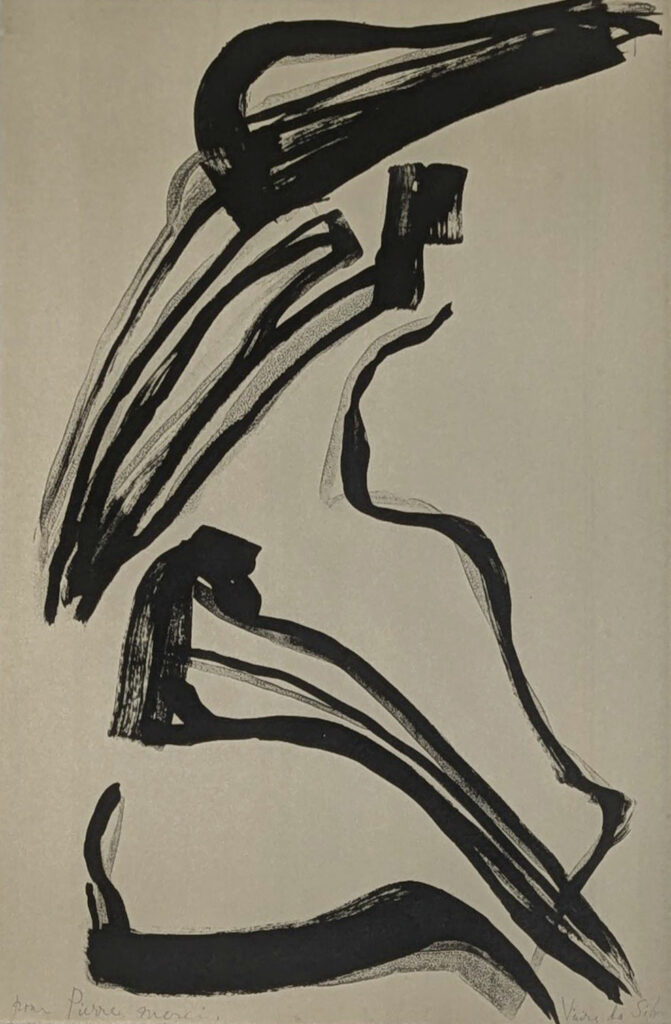

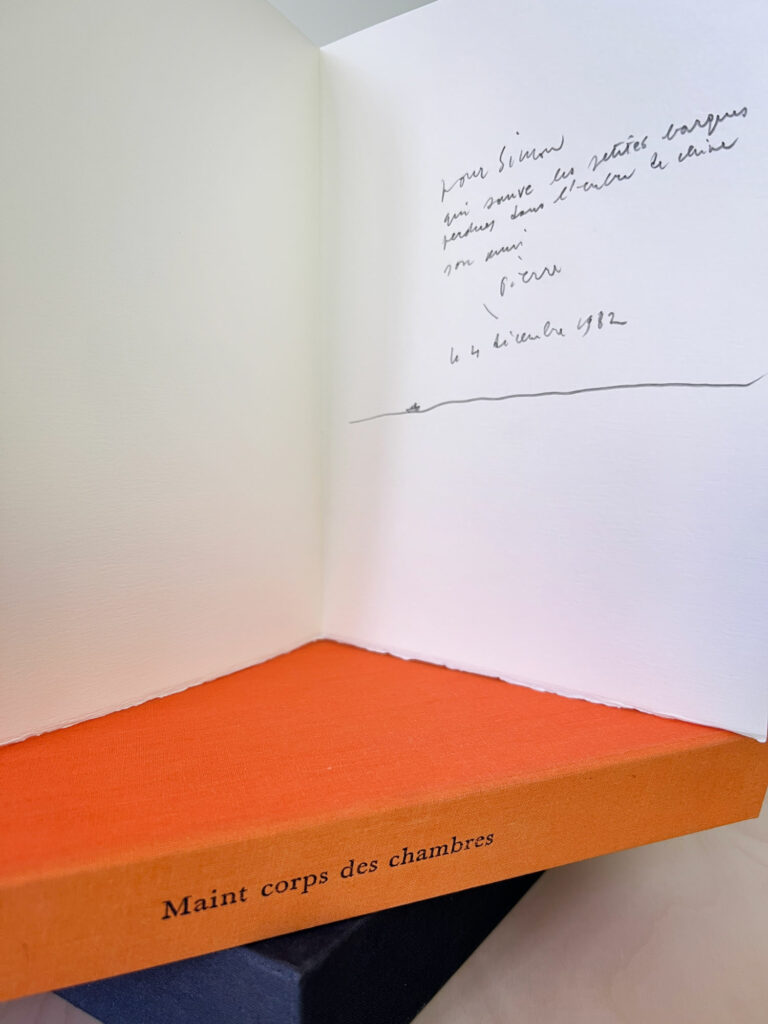

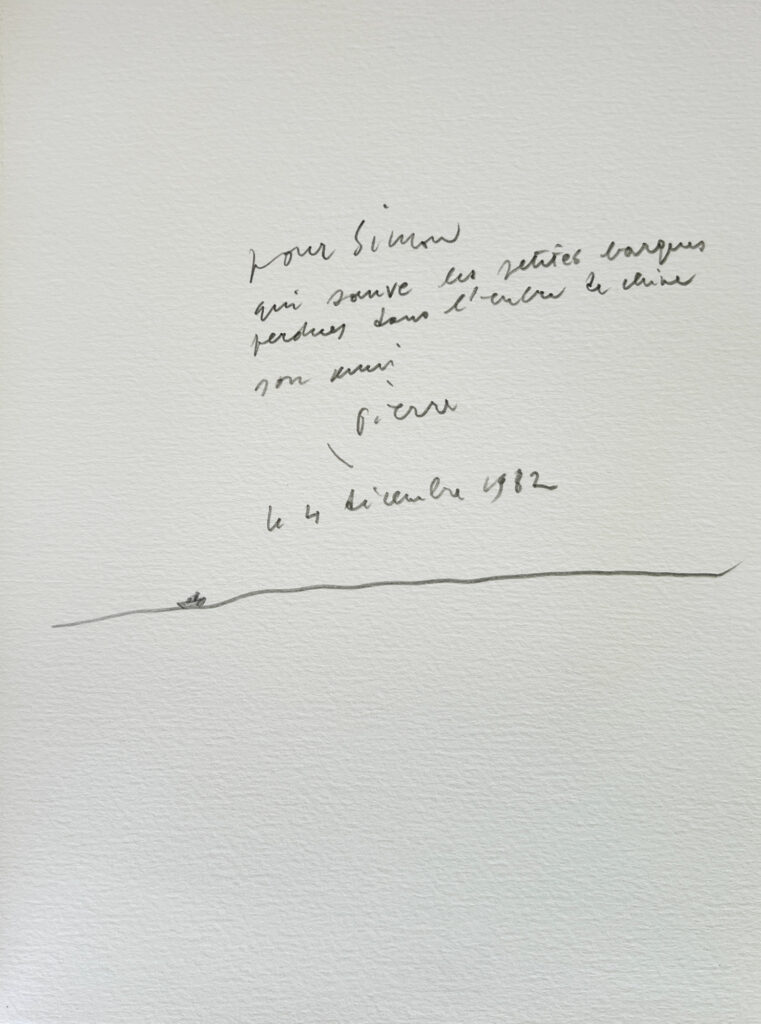

Il resta plusieurs années en contact avec Alechinsky qui lui envoya régulièrement des cartes et lui dédicaça notamment son exemplaire Maint Corps des Chambres par cette mystérieuse annotation : “pour Simon / qui sauve les petites barques / perdues dans l’encre de chine / son ami / Pierre / le 4 décembre 1982”.

Pierre Alechinsky lui offrit également une encre réalisée en 1976 intitulée Bon Moment.

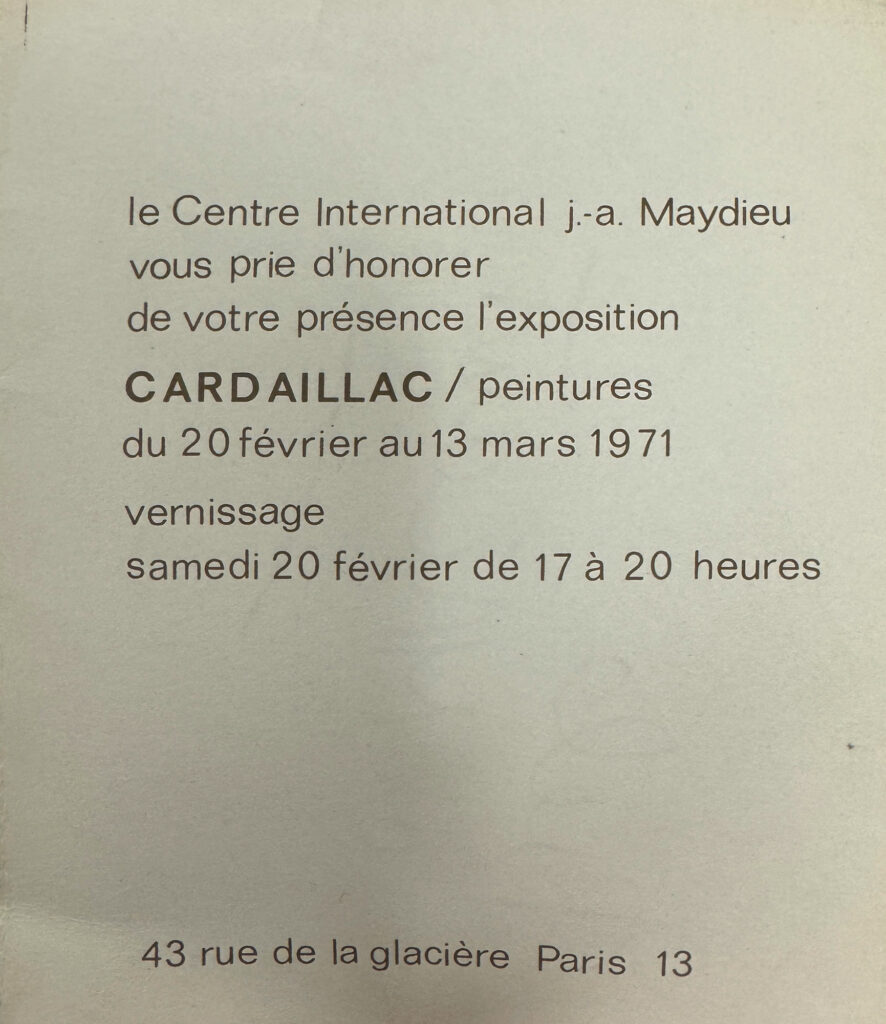

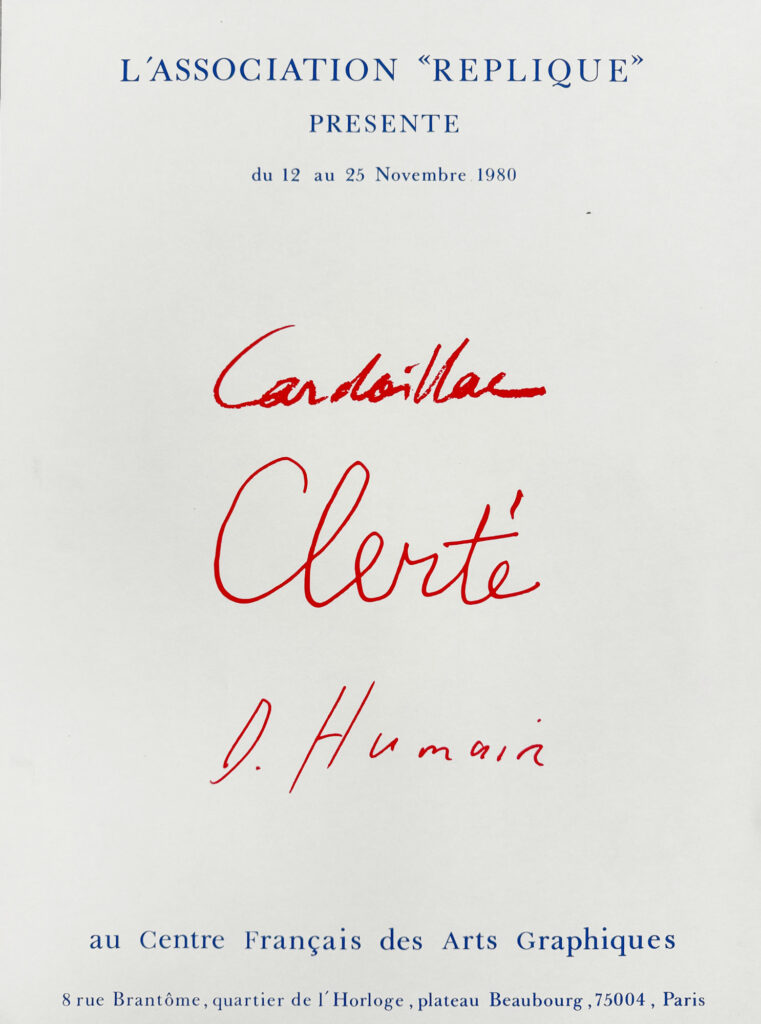

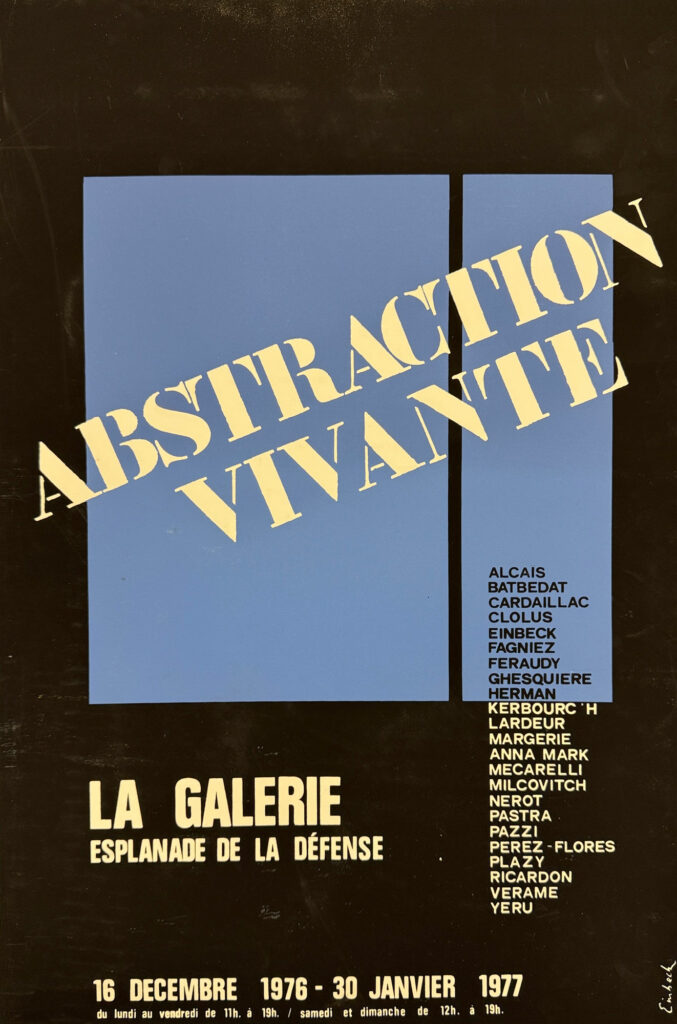

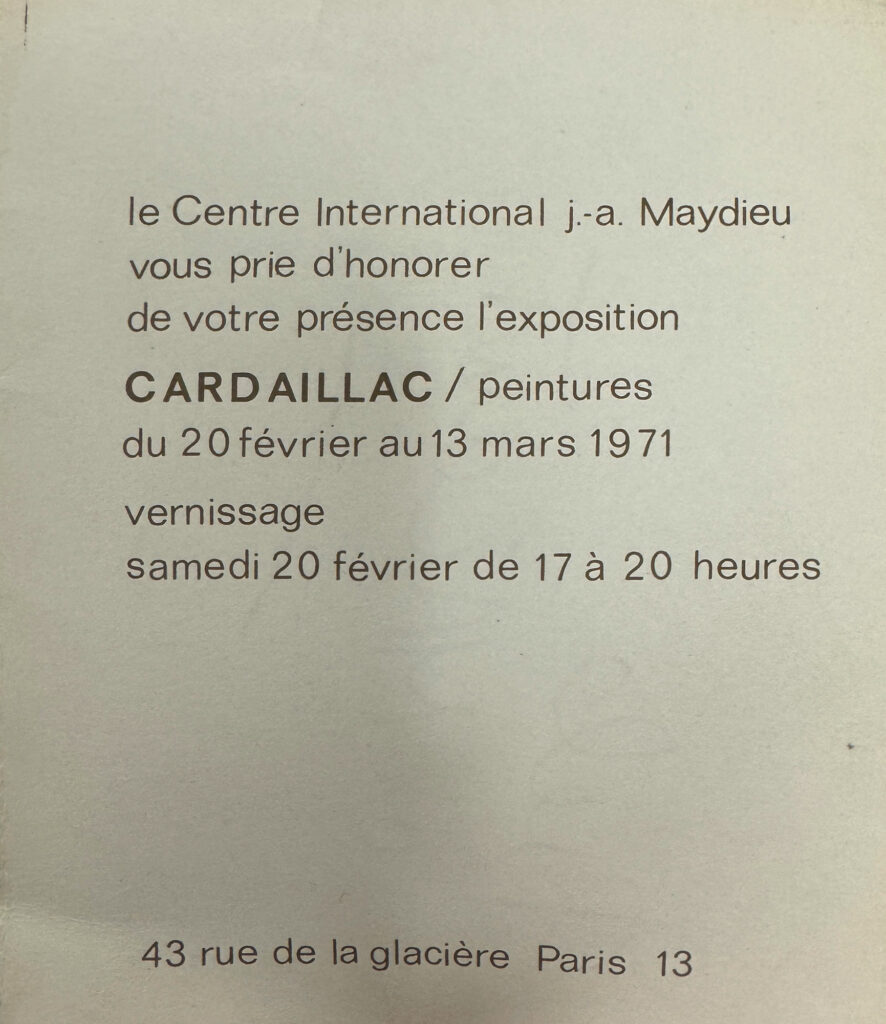

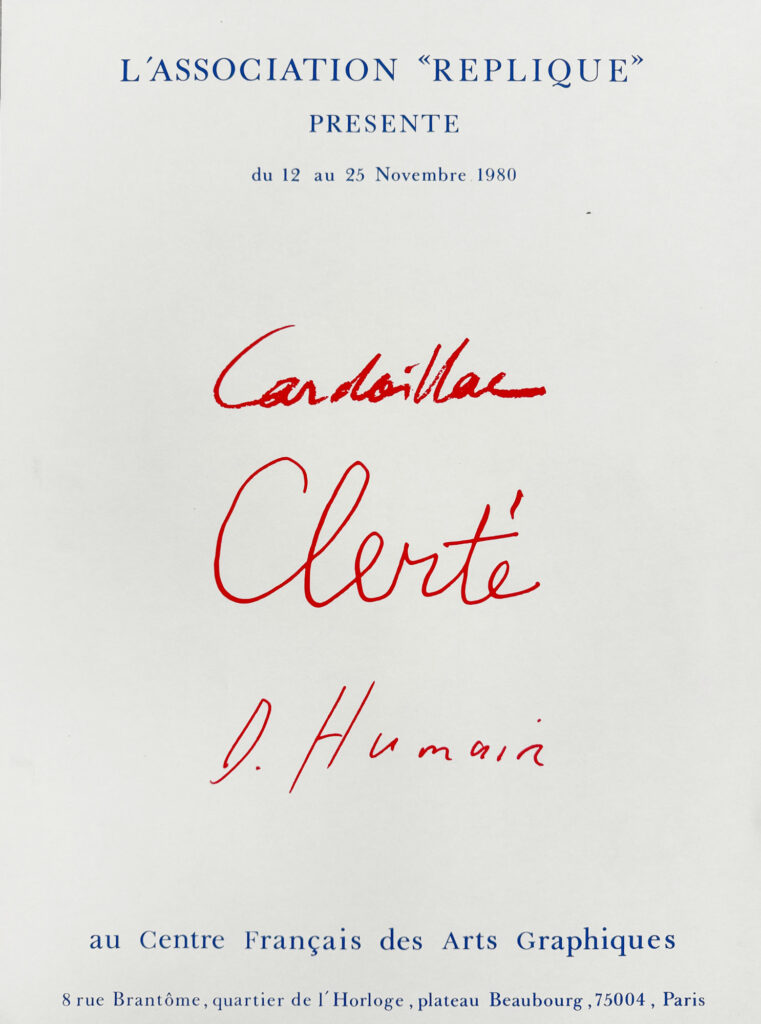

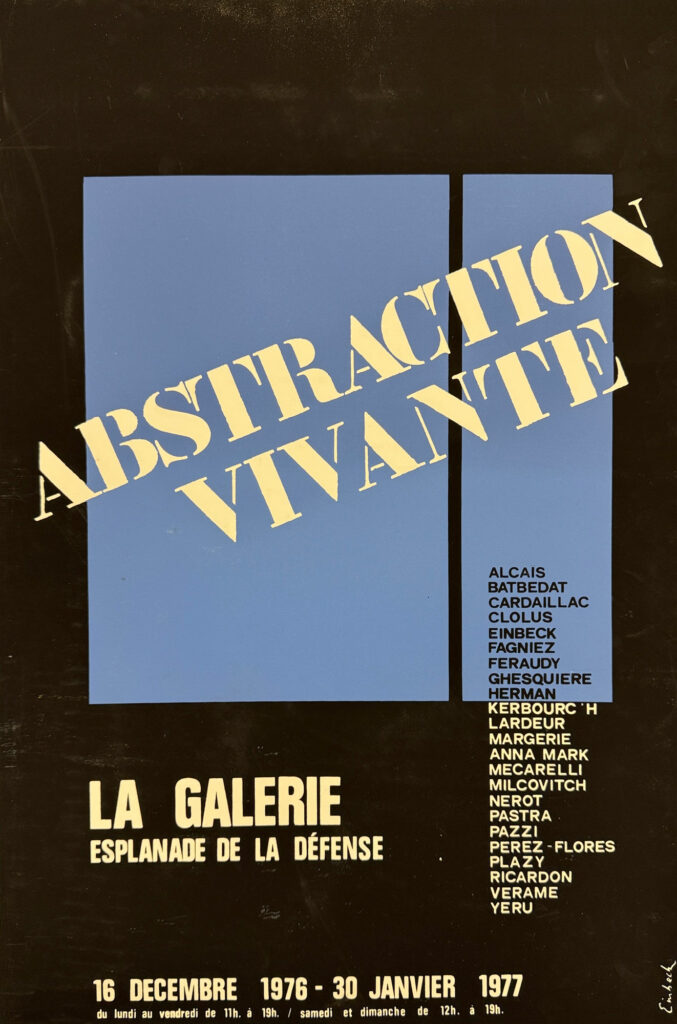

Outre les expositions précédemment évoquées dans la partie sur les collectionneurs américains, Simon de Cardaillac fut exposé à plusieurs reprises au cours de sa carrière. Après les expositions de 1956 aux Salons Comparaisons et Réalités Nouvelles, sa peinture est présentée lors d’une exposition personnelle tenue au Centre International J.-A. Maydieu de Paris du 20 février au 13 mars 1971. Par la suite, il participe notamment à l’exposition Abstraction Vivante, organisée par Gilles Plazy à la Galerie de l’Esplanade de La Défense, de décembre 1976 à janvier 1977. L’année suivante, il expose à la Biennale de Mantoue. En 1980, il est invité à exposer aux côtés de Pierre Alechinsky, Karel Appel ou encore Asger Jorn à l’abbaye Saint-Savin sur Gartempe, pour l’exposition Boomerang. En 1980, il fait également partie des trois artistes exposant au Centre National des Arts Graphiques de Paris sur le plateau Beaubourg, avec Jean Clerté et Daniel Humair.

En 1981, il expose sur le thème de la “Musique et Peinture” accompagné par Jean-Pierre Rampal à la flûte et Robert Veyron-Lacroix au clavecin, pour les Amis de la Musique de Rueil-Malmaison. En 1984, il participe à une exposition de groupe autour de la pièce de théâtre de Claude Confortès, Les Argileux, à la galerie Esquisse dans le 6eme arrondissement de Paris. Enfin, sa dernière exposition personnelle connue fut organisée au Danemark, près de Copenhague, en 1988, à l’occasion de l’année culturelle franco-danoise. Elle eut lieu à Klampenborg dans la galerie Chris Evers et également en France, dans la galerie de Jean Perret, Style Marque, à Paris. Le thème de cette exposition était “Un peintre, une marque” et était sponsorisé par le groupe danois Carlsberg, donnant lieu à une série d’œuvres autour de la marque Carlsberg, comme nous l’aborderons dans cette seconde partie consacrée à l’œuvre de Simon de Cardaillac.

« Tu vois, je quittais ton nouvel atelier en me disant : qu’est ce qu’il a cet atelier qui n’a pas changé ? Tout y est différent et pourtant tout y est même ! Ephémère, précarité, pérennité ! »

— Entretien avec Anne de Staël, le 11 décembre 2023

Simon de Cardaillac était très sensible à la littérature et à la philosophie. Il s’intéressait particulièrement à Nietzsche et cette familiarité avec la pensée du philosophe allemand permet de mieux cerner son œuvre. Ce dernier percevait l’art comme un antidote au nihilisme, à la conviction que la vie est dépourvue de sens et de valeur. Selon Nietzsche, l’art était alors un moyen de donner un sens à la vie, même en l’absence de vérités absolues. Et, pour Simon de Cardaillac, l’art était véritablement essentiel à la vie, à l’existence, comme il put l’écrire à plusieurs reprises :

“Ces événements de la vie, les choses, les brisures, ce dont on ne parle pas, ne m’ont jamais distrait de la peinture. Je pense qu’ils en font partie. Pour moi, peindre est avant tout un choix d’existence.”

Simon de Cardaillac, le 26 juin 1988

Ces quelques phrases s’inscrivent pleinement dans la pensée de Nietzsche sur l’art, un art compris comme le moyen d’affirmer la vie face aux souffrances et aux absurdités de l’existence – un art capable de la célébrer.

“C’est un luxe qu’aujourd’hui nous puissions mettre quelque chose dans un tableau, dans un mot, non que cela concerne quelqu’un ou quelque chose, mais cela concerne “être”. Je me rappelle cette phrase inquiète de Simon : “Pour qui” “Pour quoi”, surtout pour personne et pour rien, pour être”.

Lettre d’Anne de Staël à Simon de Cardaillac

Tout au long de sa vie, Simon de Cardaillac aura eu pour “grand stimulant”[2] l’art, et celui-ci le poussa toujours à agir et à créer.

“Tout en dînant, Simon retournait très vite à ses tableaux. […] C’était quelqu’un de très vivant, très vrai, et ça c’est formidable, ça m’apportait beaucoup, l’idée du travail, du sérieux.”

Entretien avec Anne de Staël, le 11 décembre 2023

[2] F.W. Nietzsche, 1976, §24 :94

“Simon aimait beaucoup mon père [Nicolas de Staël] et je n’ai jamais eu le sentiment qu’il le copiait. Il se cherchait vraiment dans son expression personnelle. Son travail n’était pas de copier des peintres mais plutôt un beau travail personnel qui se cherche en toutes vérités.”

— Entretien avec Anne de Staël, le 11 décembre 2023

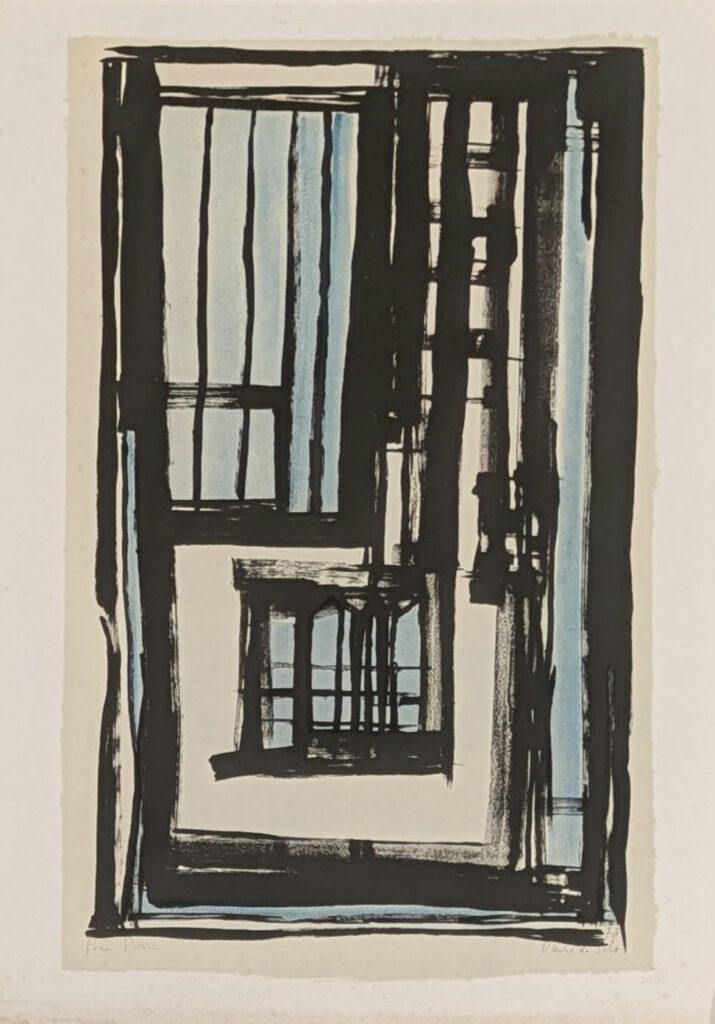

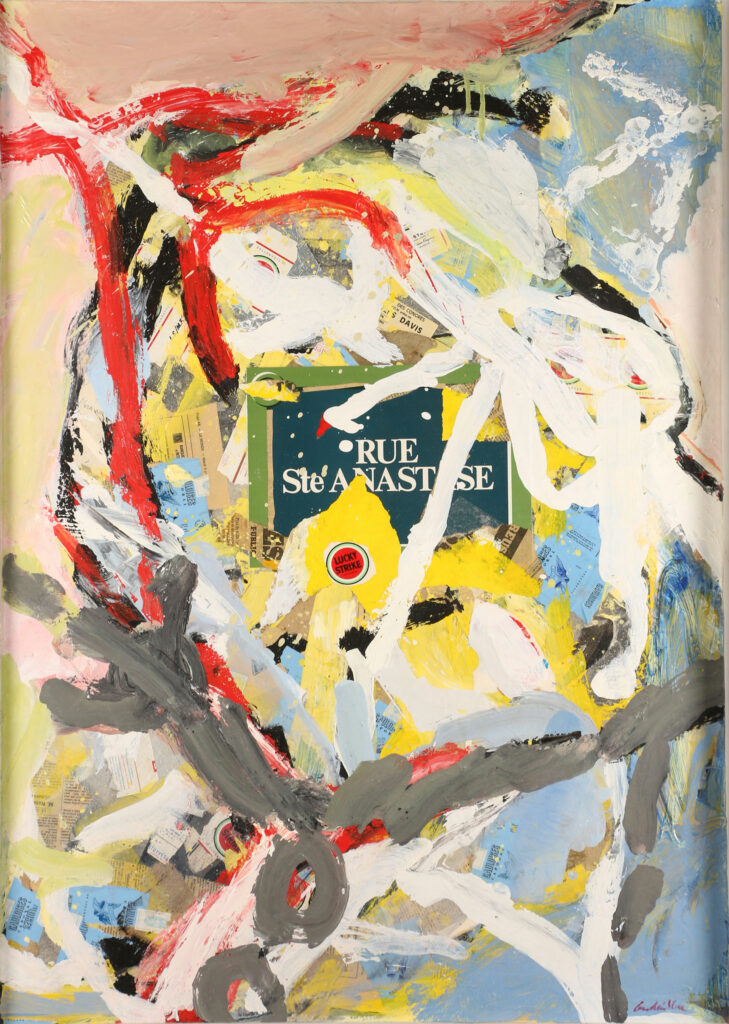

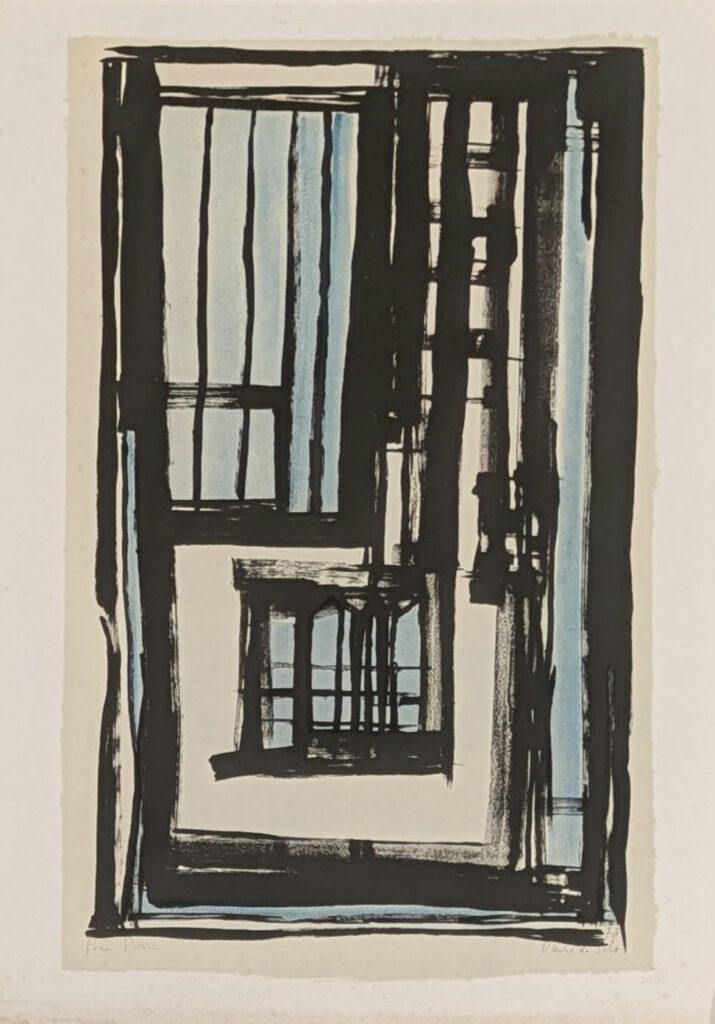

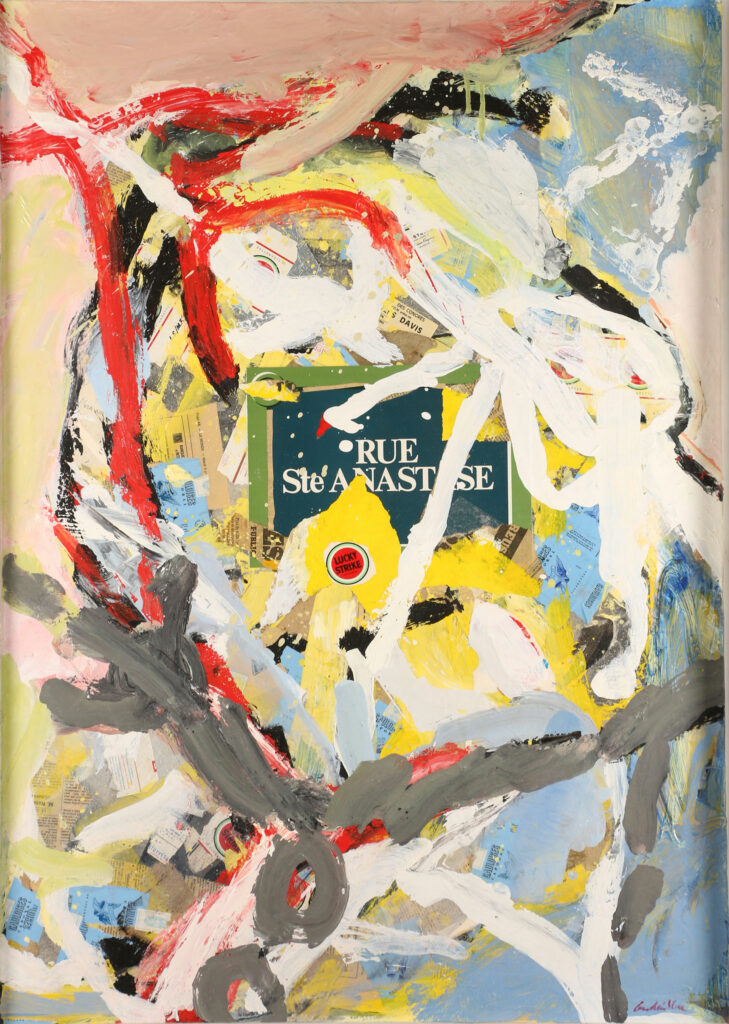

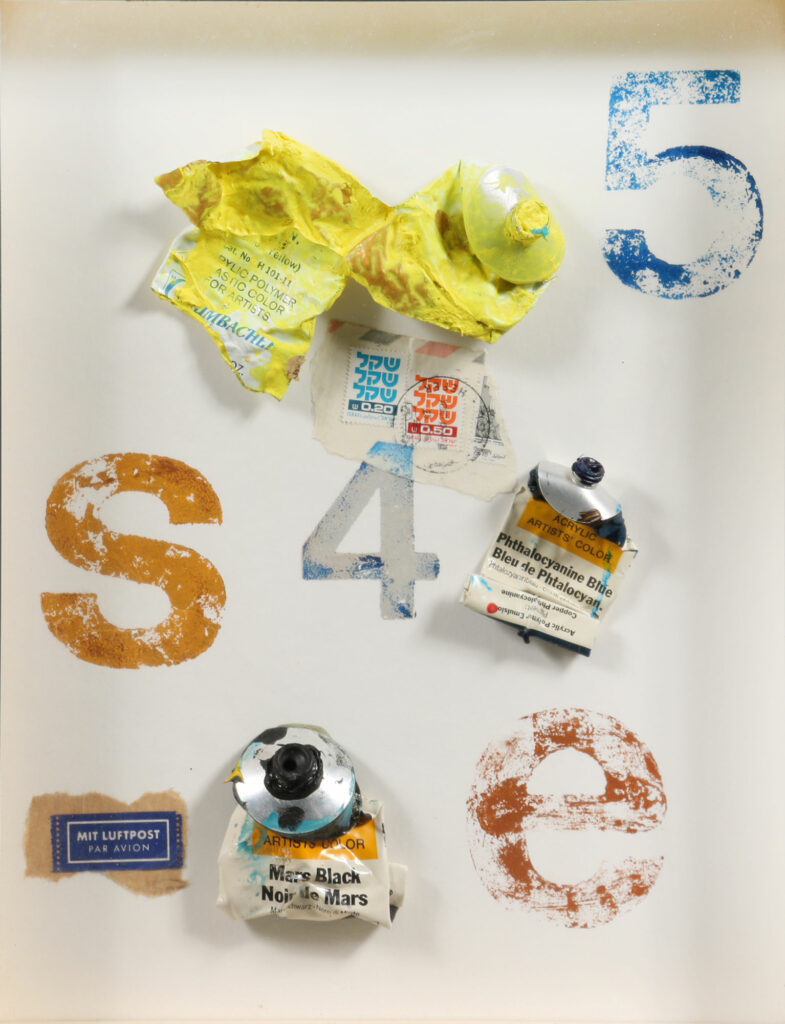

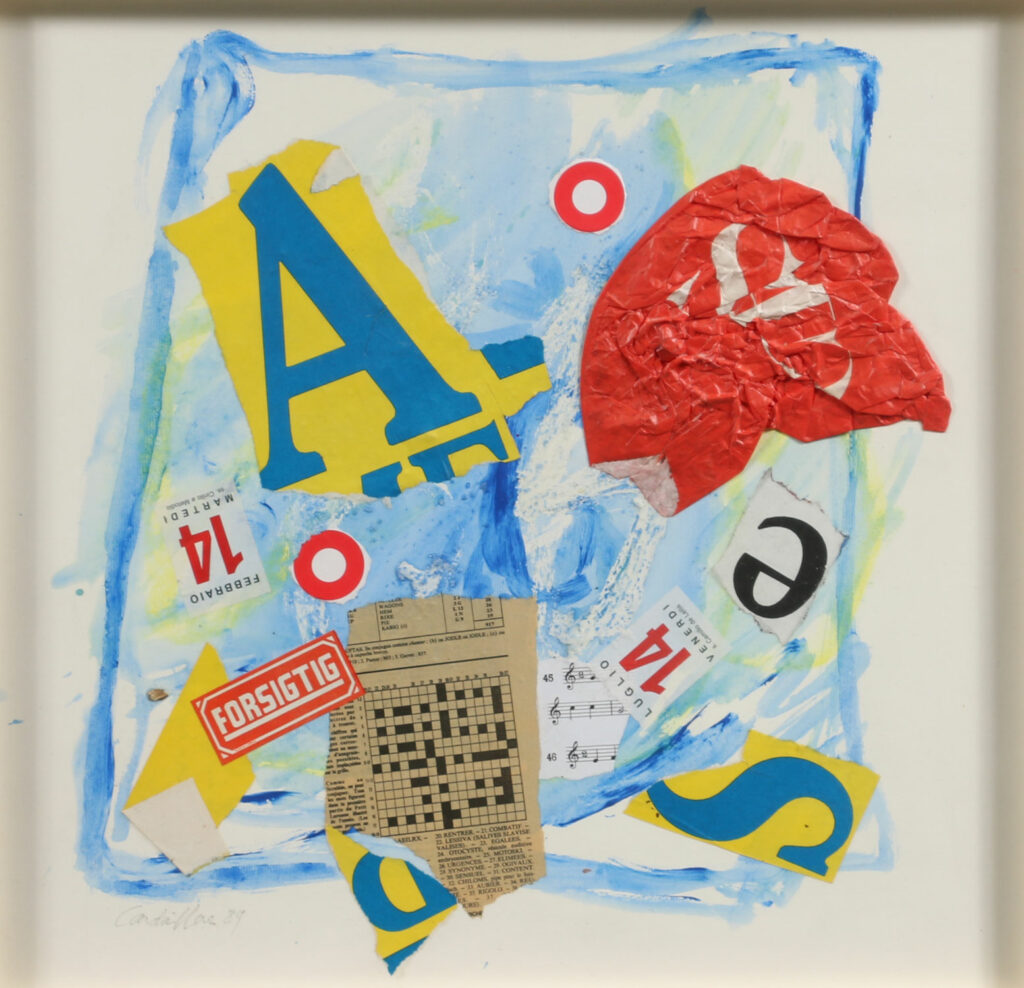

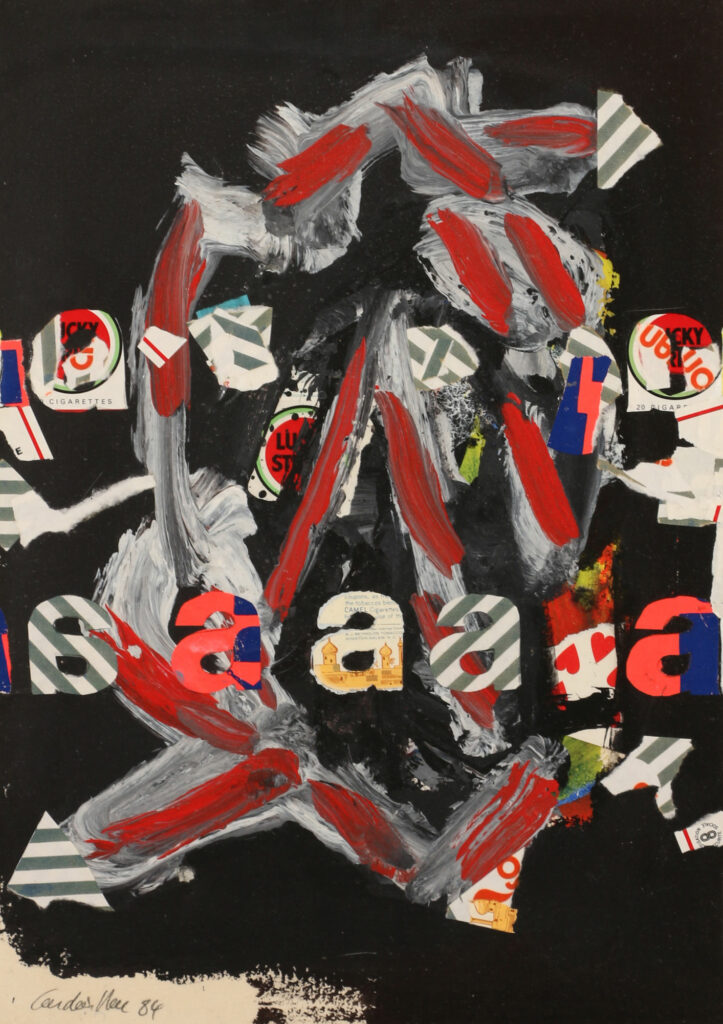

Les premières peintures de Simon de Cardaillac présentées à Vichy Enchères laissent percevoir la familiarité de ce dernier avec Nicolas de Staël, auprès de qui il a grandi, et dont l’œuvre modela sa sensibilité. Toutefois, cette influence s’estompa relativement vite, Simon semblant davantage préoccupé par la question du medium et de l’imagerie de la culture de masse. Il participa ainsi, dès 1956, au Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. Les artistes de ce mouvement considéraient l’art abstrait comme un moyen de représenter des “réalités nouvelles”, c’est-à-dire des réalités non perceptibles d’ordre conceptuel ou spirituel.

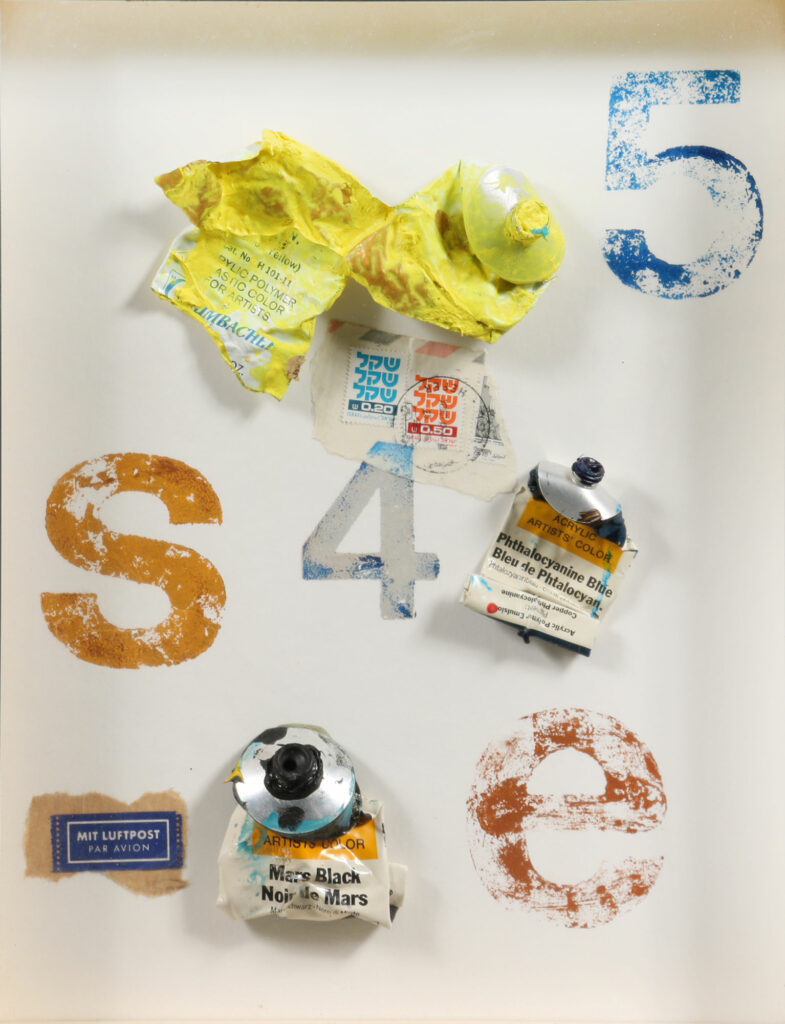

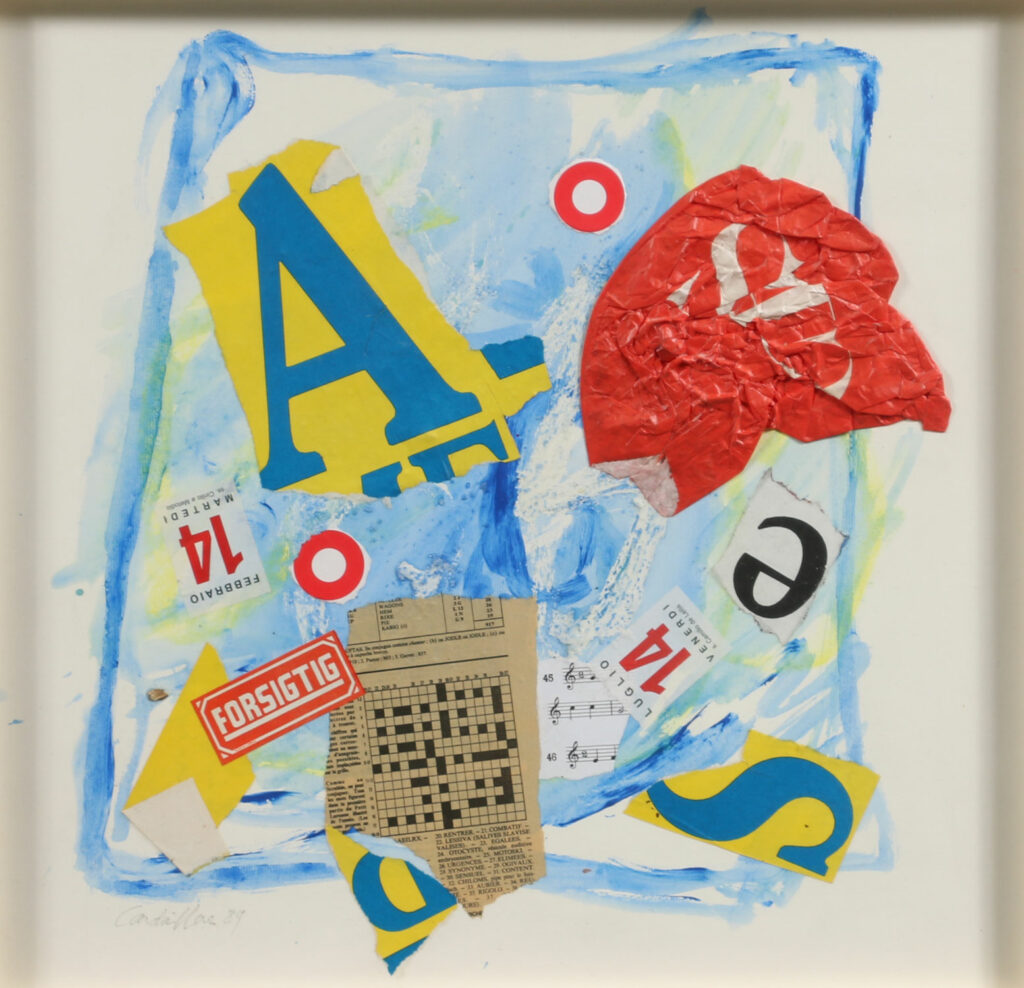

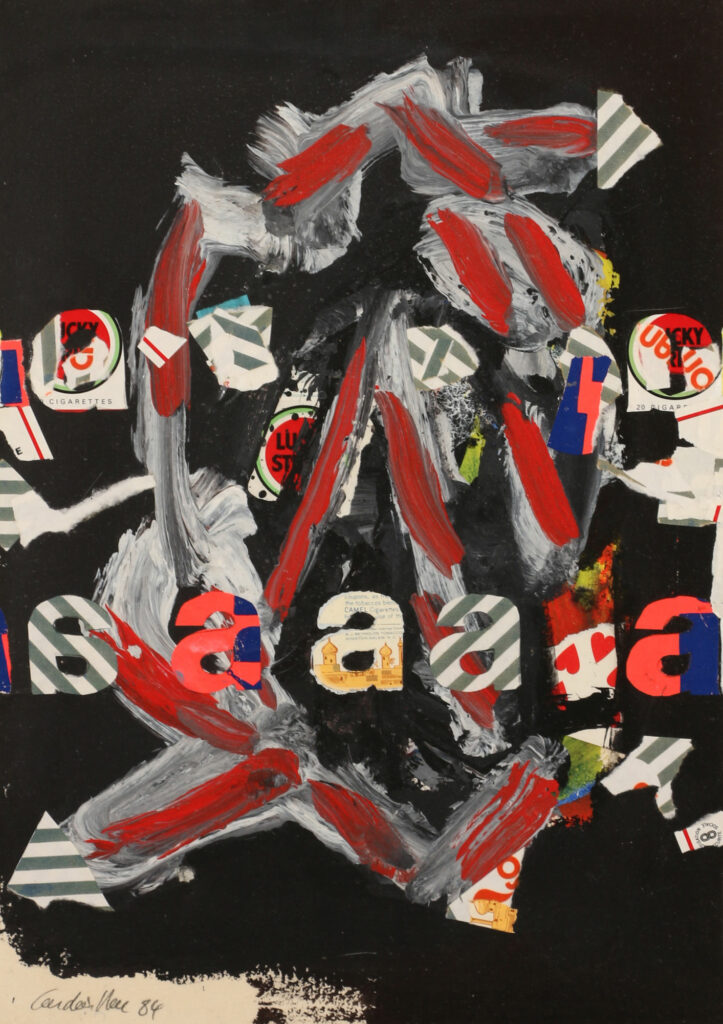

A l’image du travail de Simon de Cardaillac, ce mouvement artistique s’attachait à refléter cette nouvelle réalité façonnée par la société urbaine de consommation. Dans la lignée des ready-made de Marcel Duchamp, la réalité était alors remise au centre de la création, notamment par l’utilisation d’objets du quotidien passés au rang d’objets d’art.

L’œuvre de Simon de Cardaillac s’inscrit formellement dans ce mouvement artistique, puisque l’artiste utilisa – ou “recycla” – tout au long de sa carrière des objets issus du monde urbain, industriel ou publicitaire. Son travail reposait ainsi particulièrement sur une réflexion approfondie concernant la pratique picturale et les possibilités offertes par le médium.

Tout au long de sa vie, Simon de Cardaillac a ainsi travaillé à partir de matériaux pauvres ou bruts, souvent trouvés ou recyclés, s’inscrivant dans une veine similaire à celle de l’arte povera. Les matériaux étaient souvent choisis pour leur apparence brute et pour leur capacité à évoquer des aspects primitifs ou essentiels de l’existence humaine.

A partir de collages ou d’assemblages, il juxtaposait alors ces différents matériaux pour créer des contrastes visuels et tactiles, explorant notamment les thèmes liés à la reproduction industrielle et à la société de consommation. Réalisées à partir de matériaux modestes, les œuvres de l’artiste créaient alors un dialogue entre l’art et le monde moderne, cherchant à démystifier l’acte créatif et à réduire l’art à ses éléments fondamentaux. Simon expérimentait avec la couleur, la texture et la surface, souvent en utilisant des méthodes simples et directes comme le collage, l’assemblage, la photographie ou la gravure. Toute sa vie, il rejeta l’idée d’un art devenu objet de luxe ou de marchandisation, privilégiant des approches plus démocratiques et accessibles, et allant jusqu’à refuser de vendre ses œuvres et de collaborer avec des marchands. Lorsque l’écrivain et critique d’art Charles Juliet s’intéressa à son travail et demanda à l’interviewer pour écrire sa biographie, Simon de Cardaillac refusa.

Cette réflexion autour du médium et de l’imagerie de la culture de masse le conduisit à réaliser une série autour du logo publicitaire de la marque Carlsberg. Une exposition fut organisée près de Copenhague en 1988 dans la galerie Chris Evers, et également en France, à Paris, dans la galerie de Jean Perret Style Marque. Toutes les œuvres réalisées avaient alors “pour motifs des bouteilles, des étiquettes ou des caisses de bière.”[1]

[1] Kjeld B. Nilsson, « Øl er øl, men også dansk-fransk kultur », Berlingske Tidende, Copenhague, 16 juin 1988.

“Certaines marques sont devenues tellement importantes dans notre musée imaginaire qu’elles sont des points de repère pour le voyageur qui dans toutes les grandes villes du monde retrouve leur graphisme présent et fluorescent. […] Carlsberg en est l’exemple type. […] Rouge et blanc est le rapport le plus fort en signalétique. Style Marque […] a eu envie de rendre hommage à cette signature en s’associant à Simon de Cardaillac dans une vision poétique et picturale de la marque. Le peintre dépassant les contraintes du graphisme a utilisé la marque et différents éléments de son environnement comme une palette de formes et de couleurs. C’est un angle de vue insolite mais enrichissant pour l’imaginaire de la marque, qui démontre la force de cette signature qui, sortant du cadre strict des normes, trouve une nouvelle puissance d’évocation sans rien perdre de sa personnalité.”

Jean Perret, directeur de Style Marque, 1988

Cet évènement fut un succès, comme le confirme cette lettre de Chris Evers : “people have shown a lot of interest in your paintings. I have actually sold all the oil-paintings that I bought from you in Paris.”[1] Toutefois, une partie des œuvres que Simon de Cardaillac avait exposées au Danemark ne lui fut pas restituée et celui-ci commença à rencontrer des difficultés, ne pouvant rien présenter lors de la FIAC.

[1] Chris Evers House of Contemporary Art, lettre de 1988

Cette question du médium est étroitement liée à celle de la signalétique, une autre thématique prédominante dans l’œuvre de Simon de Cardaillac. La signalétique, qui englobe les panneaux de signalisation, les symboles graphiques, les logos et d’autres formes de communication visuelle standardisée, fut une source d’inspiration inépuisable pour l’artiste qui intégra régulièrement des éléments issus de cette imagerie dans ses créations. En sortant ces éléments familiers et en les plaçant dans des contextes nouveaux et surprenants, il s’amusait alors à créer des dialogues entre les différents modes de communication visuelle et les significations culturelles portées par ces signes. Par ce processus, Simon de Cardaillac nous invite à porter un nouveau regard sur notre environnement et à nous interroger sur nos modes de vie, souvent contraints par des comportements mécaniques répondant à des codes intégrés dès le plus jeune âge.

Cette nouvelle vision du monde urbain, à la fois poétique et cynique, soulève notamment la question de la liberté, comme il l’évoque dans ce texte poétique :

“Mais revenons à notre quotidien – ici pays moins au nord mais aussi pays de pluie qui nous fait courber la tête de manière attavique et ancestrale comme des chiens – et regardons se déplacer nos pieds sur l’asphalte mouillé et noir. […]

Nous lisons rapide, liaison rapide, directe du signal, regard à la compréhension du message donné – barrière rouge, stop, danger, flèches impératives de direction. Même si votre raison veut aller ailleurs, vous obéissez au sens de la flèche plus vite que votre raison désobéissante.

Le signe est là et… son signal.

Nul n’y échappe. Il est notre réalité, notre quotidien. […]

L’esthétique de notre environnement devient notre musée permanent.

L’œil commence-t’il à fonctionner mieux ? Rentrons-nous dans l’ère du regard ?

Le feu passe au rouge – Stop –

S’il fallait lire “arrêtez-vous tout de suite ! Instantanément appuyez votre pied sur la pédale frein” : accident… mais, non. Le signal rouge, d’un bref clin d’œil a tout déclenché – réflexe direct – pas de lecture.”Simon de Cardaillac, texte rédigé en avril 1988

Simon de Cardaillac intégrait ainsi la signalétique dans ses œuvres afin d’explorer l’esthétique de l’environnement urbain moderne et de jouer avec ses codes visuels, défiant les attentes du spectateur et brouillant les frontières entre l’art et la vie quotidienne. L’usage de la signalétique découlait également de son intérêt pour l’art pauvre et lui permettait de créer des œuvres visuellement percutantes aux couleurs franches.

Outre ces éléments de signalétique urbaine, Simon de Cardaillac ajoutait régulièrement dans ses compositions des caractères numériques et typographiques. Il était particulièrement intéressé par la force symbolique des nombres et rassemblait dans son atelier un tas d’objets figurant des nombres, tels que des pages de calendrier, des cartes de jeux, des points de fidélité de stations services, des pochoirs ou encore des tampons de chiffres. Il s’en servait pour faire des collages ou pour tamponner ses œuvres de chiffres. Cette fascination pour les nombres s’incarne aussi dans une série de cartes de vœux, réalisées à partir de techniques mixtes et gravées, qu’il adressait à ses proches, à l’instar d’Anne de Staël qui en fit le commentaire en 1997 :

“Mon cher Simon, que c’était gentil ce 1997 dans son ocre jaune soleil, cet terre et le grand 7 comme une fenêtre ouverte sur le passage des nuages de l’ocre et sur l’année ! Tous les chiffres seuls jusqu’à 9 me fascinent, mais dès qu’il y en a plusieurs, le multiplié ralentit l’émotion d’un beau chiffre seul. Ce doit être qu’un chiffre retient “qu’un jour, un jour on est venu au monde” et contient toute l’horlogerie du monde dans lequel nous nous perdons !!/”

Lettre d’Anne de Staël à Simon de Cardaillac, 1997, archives familiales

Simon de Cardaillac découpait également des pages de journaux pour ses collages ou pour en extraire certaines lettres. L’usage des caractères dans ses œuvres lui servait à explorer les possibilités expressives du langage écrit et des symboles numériques. En incorporant ces signes, parfois des phrases entières, Simon ajoutait différents niveaux de lecture et de sens à ses créations, et proposait une interaction dynamique entre le visuel et le verbal. En déconstruisant les mots et les nombres, en les isolant, en les fragmentant ou en les combinant de manière non conventionnelle, il examinait alors leur structure, leur signification et leur sonorité. Enfin, il les utilisait pour créer des motifs visuels intéressants et pour ajouter une dimension tactile au support.

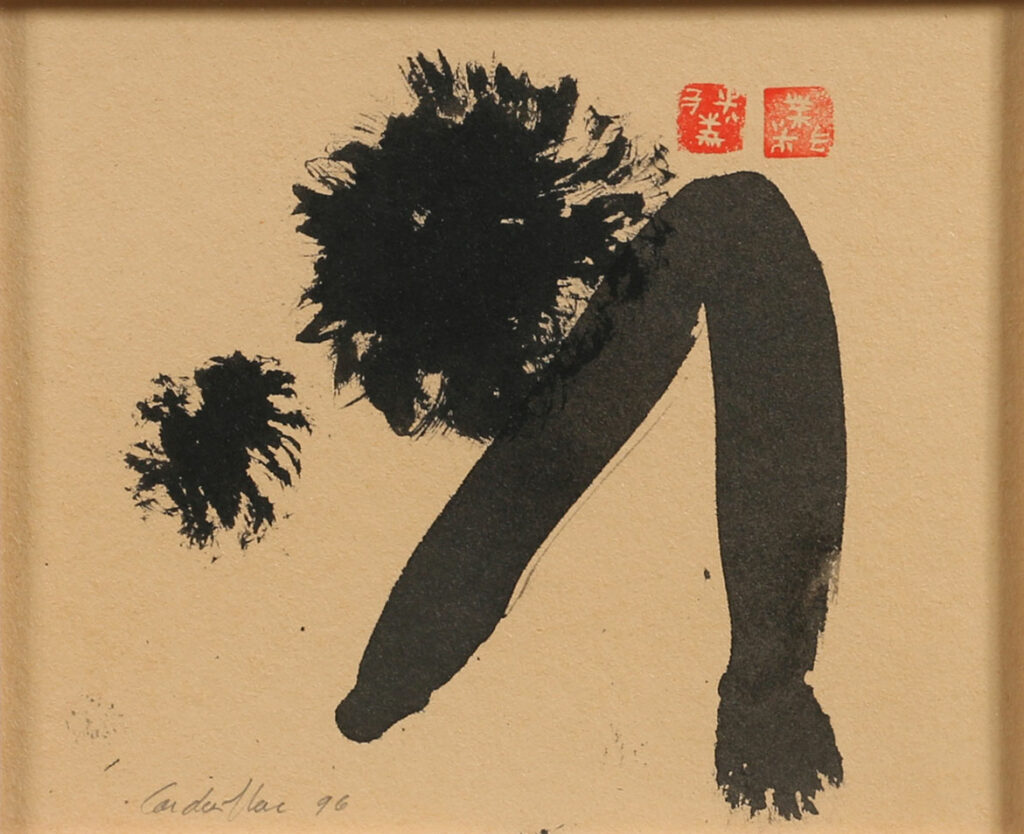

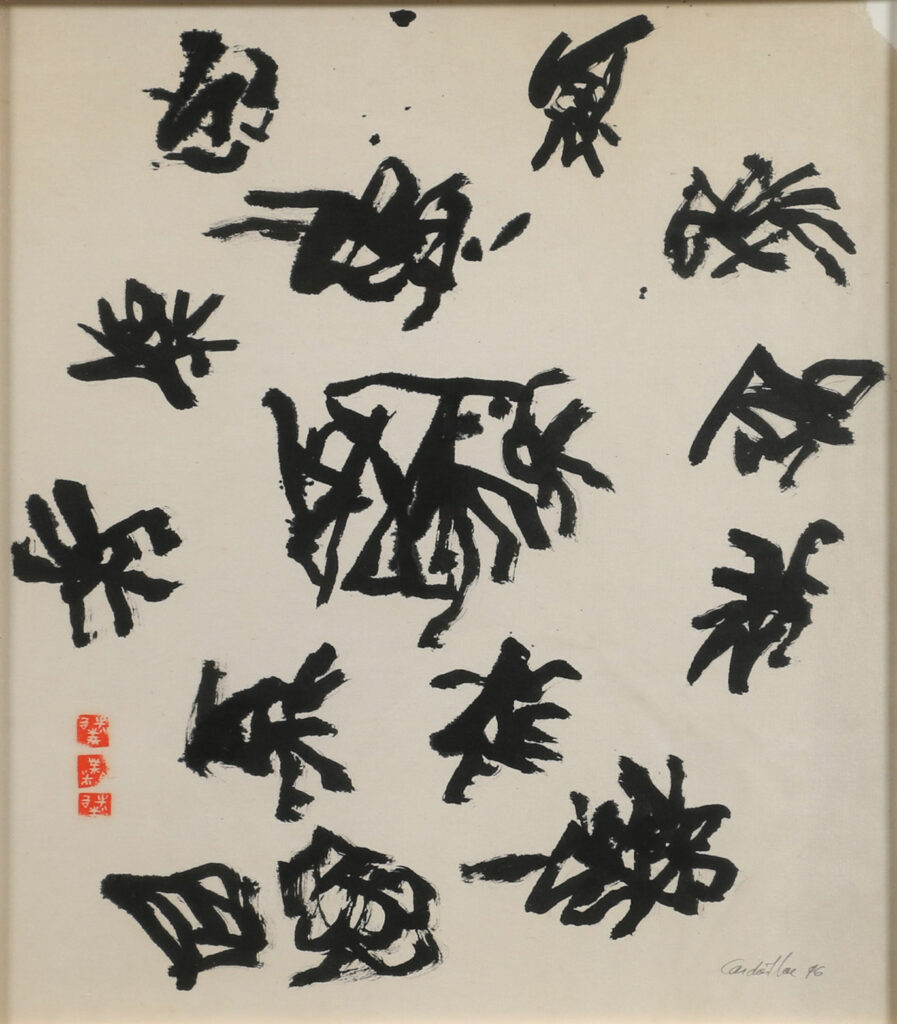

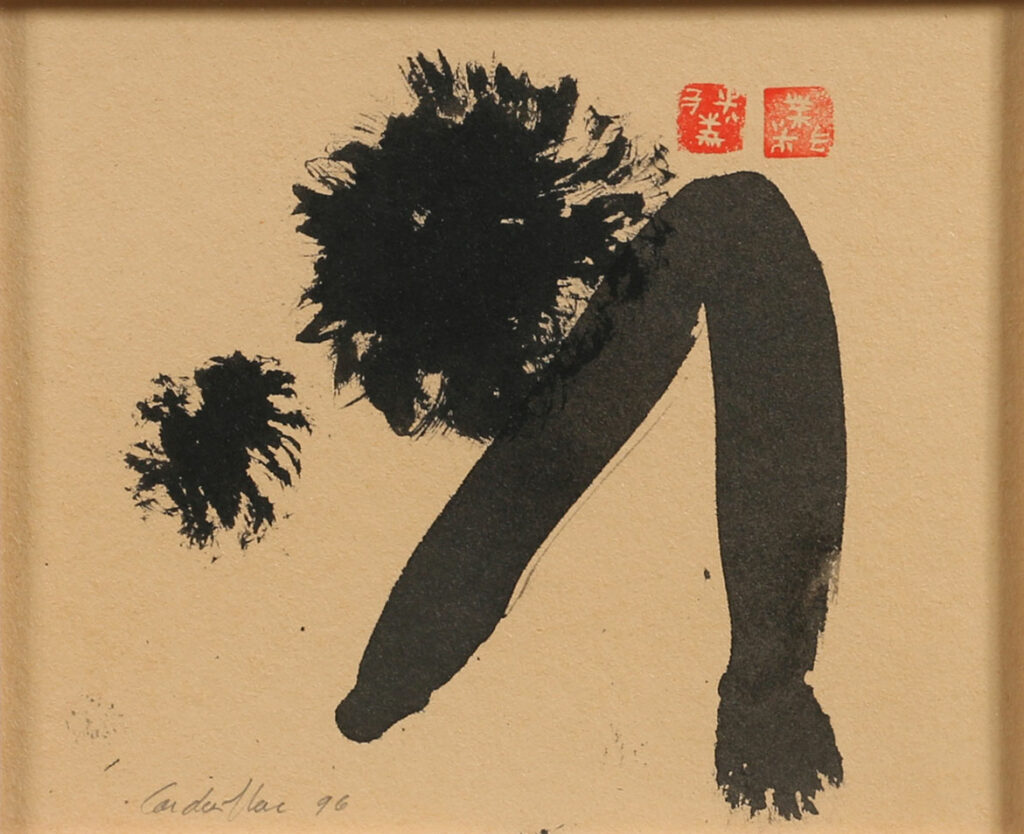

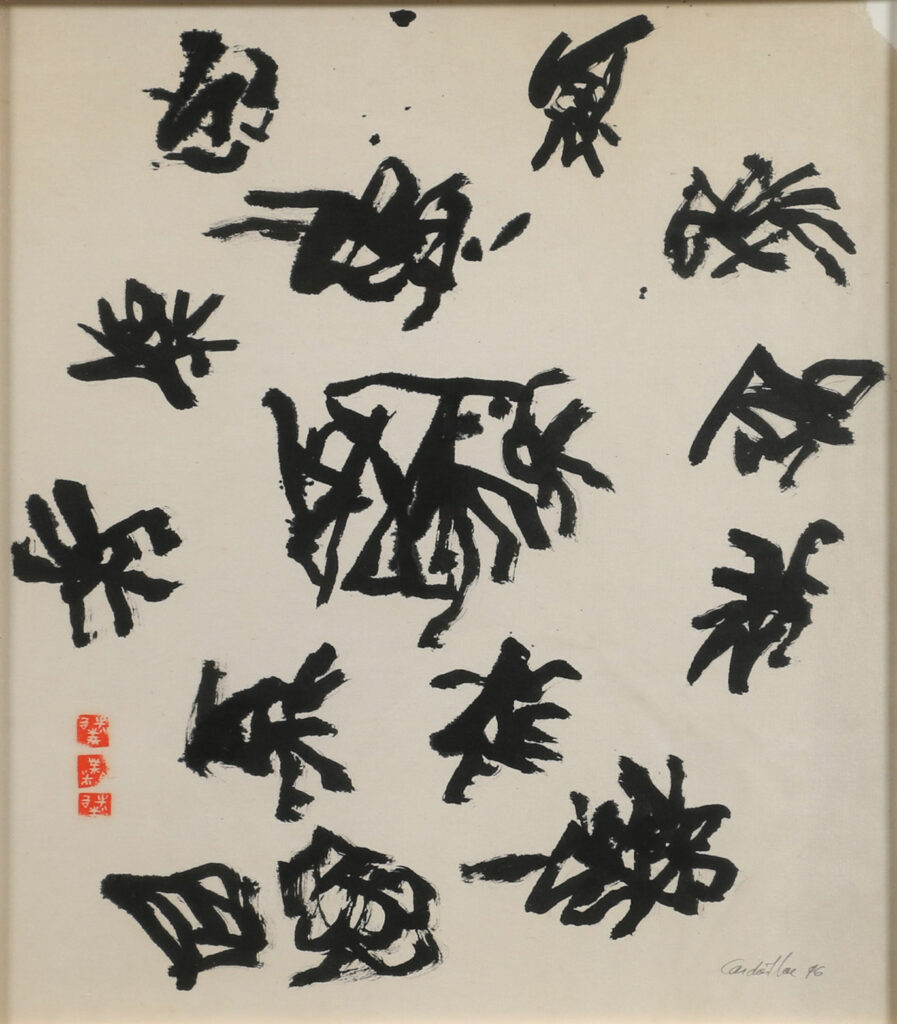

Par ailleurs, cette fascination pour les caractères et symboles fut également à l’origine de séries de peintures, à l’encre ou à l’acrylique, réalisées et gravées dès les années 1980. Celles-ci, et plus particulièrement les séries en noir, sont une évocation des calligraphies asiatiques qui fascinaient l’artiste :

“Calligraphie chinoise ou japonaise – Idéogrammes millénaires – Hiéroglyphes tactiles – Sensualité du Regard – Silences chargés de subjectivités, libertés dans le code mais, hors du code – Le regard illustré et non pas le regard commenté et lu.”

Simon de Cardaillac, texte rédigé en avril 1988

Peut-être aurions-nous dû commencer par la photographie pour commenter l’œuvre de Simon de Cardaillac. Elle semble, en effet, servir de point de départ à la conception d’un bon nombre de ses œuvres. Nous conservons en effet plusieurs séries de photographies réalisées par l’artiste qui révèlent son intérêt pour les signes, la signalétique urbaine et l’architecture. Ces photos ont la particularité d’être toujours très zoomées afin d’isoler un élément en particulier. Ainsi, lorsqu’il photographie Paris, aucun élément n’identifie en réalité la capitale et il pourrait s’agir de n’importe quelle autre ville. Ces photos figurent essentiellement des murs ou des supports de peintures industrielles et/ou d’affiches publicitaires décollées ou arrachées.

Elles présentent également des façades taguées, des nombres sur des vitrines, des passages piétons, des bandes de marquages rouges et blanches, des flèches de signalisation, des éléments architecturaux recouverts de couleurs criardes, – ou juste l’asphalte… Ces photos, que ce soit par leur composition, motifs et couleurs franches, pourraient être confondues avec les assemblages de ses peintures de Simon de Cardaillac.

Toutes fournissent des motifs, des textures, des jeux de lumière et de compositions qui peuvent être interprétés de manière abstraite, et il est évident que ces images sont à la source d’un grand nombre de ses compositions picturales.

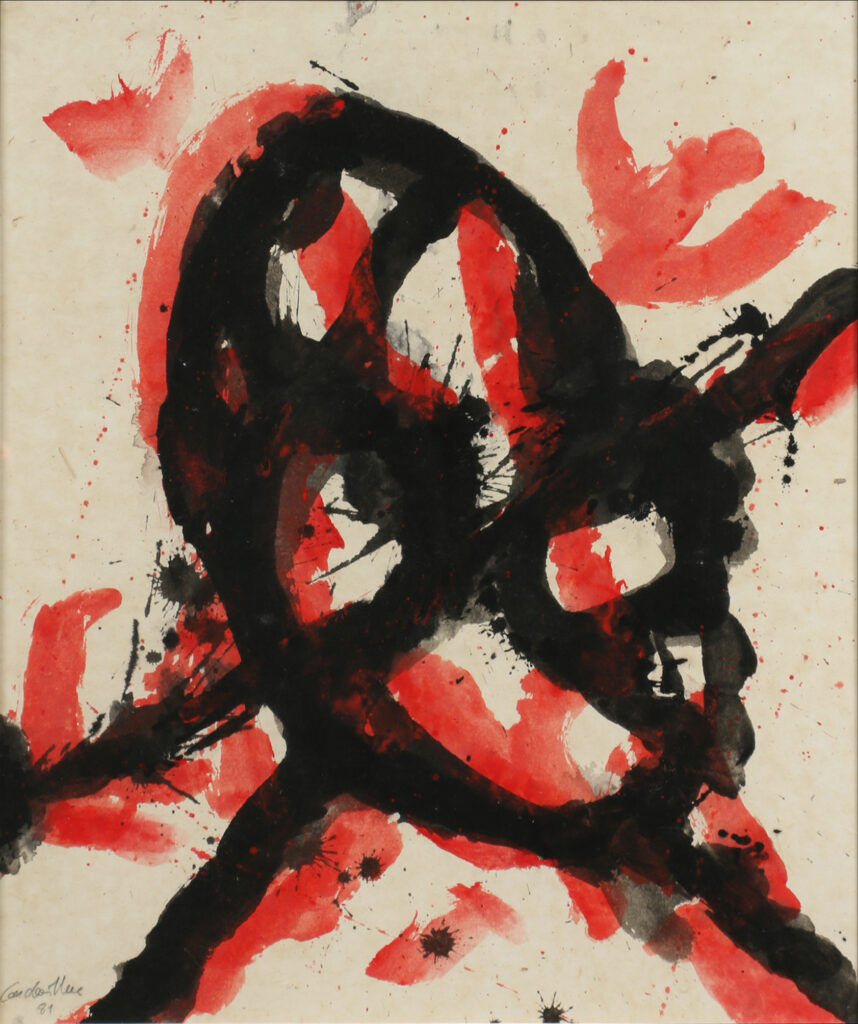

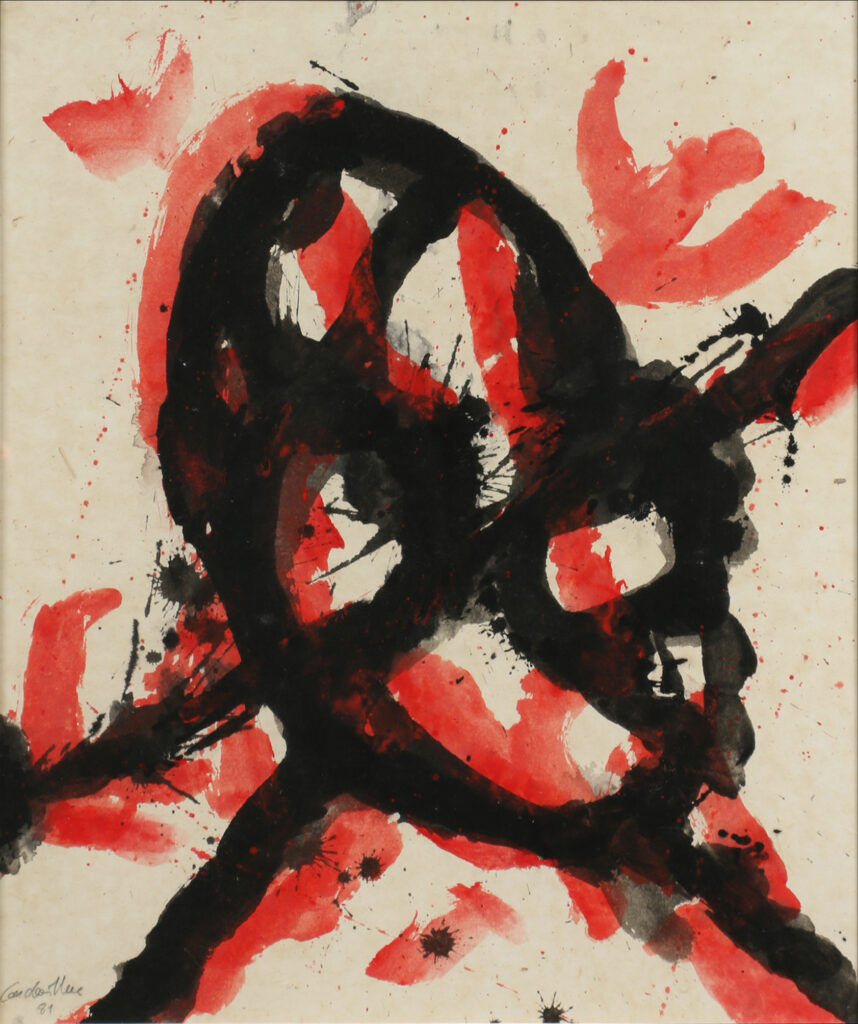

Simon de Cardaillac peignait de façon sensible et intuitive. La spontanéité de son geste, renforcée par des couleurs vives, des formes fluides et des compositions dynamiques, affirme sa singularité.

De manière générale, on observe que les œuvres de Simon de Cardaillac sont souvent caractérisées par des couleurs tranchées et contrastées, ainsi que par des formes organiques et fluides, qui laissent transparaître la relation que le peintre entretenait avec la poésie. Une partie de son œuvre est, de ce fait, proche de l’abstraction lyrique, ce qui n’a rien d’étonnant compte tenu des liens qui unirent Simon de Cardaillac et Hans Hartung toute leur vie durant.

Ne manquez pas l’exposition autour de la redécouverte de Simon de Cardaillac organisée par Vichy Enchères le 19 juin 2025 et qui donnera lieu à la vente de son fonds d’atelier.

“I loved Simon very much. When I was with Simon I felt immersed in the reality of living thought. […] He was always very reserved, very unique, and it was wonderful. He spent his time working. I know he was very earnest and true, not seeking fame at every stroke of the brush. Not achieving fame doesn’t stop you from being an excellent painter. […] He was a good painter who deserves to have his paintings brought out of the shadows. […] And I will be able to bring back the veils of a memory, what an evening in that studio brought me…”

Anne de Staël, 11 December 2023

“I was born in Nice on 10 February 1932. My father told me it was the night the cardboard effigy of Her Majesty Carnival was burned to death, in the tragic and popular finale to the jubilant Carnival celebrations. I briefly searched for a meaning in the coincidence of this event and my birth – but having realized that I was rather prone to chills and other colds, I quickly stopped all speculation in this direction.”

— Simon de Cardaillac, 26 June 1988

“Only the core group of childhood friends attended the baptism, celebrated by Abbé Krebs. There was Jeanne de Cardaillac, the godmother, and her son Simon.”

“Only the core group of childhood friends attended the baptism, celebrated by Abbé Krebs. There was Jeanne de Cardaillac, the godmother, and her son Simon.”

Laurent Greilsamer, Le Prince foudroyé, la vie de Nicolas de Staël, Fayard, 1998, p.97

The close relationship between the two families meant that Simon de Cardaillac grew up in close contact with Nicolas de Staël and his family, and this had a lasting influence in shaping his artistic eye.

These long hours spent with the Staëls had an impact on Nicolas de Staël’s work – as evidenced by two rare portraits of Jeannine Guillou in a yellow kerchief. Indeed, while Jeanne de Cardaillac was witnessing the first of Nicolas de Staël’s famous portraits of Jeannine Guillou being painted between 1941 and 1942, she asked the painter to stop working :

“Don’t touch this painting anymore, Nicolas! Please, it’s perfect. All of Jeannine is there,” cried out Jeanne de Cardaillac during an impromptu visit.

- Jeanne! I’m just getting started…

- If you give it another stroke, you’ll destroy everything!”

Staël laughed. Fate intervened before he could even reach the end of his strength. Jeanne, I gift it to you. It’s for you…”

Laurent Greilsamer, Le Prince foudroyé, la vie de Nicolas de Staël, Fayard, 1998, p.99

The painting thus joined to the Cardaillac family home, who lived under the watchful eye of Jeannine Guillou for many years. Nicolas de Staël went on to paint a second portrait of her.

During his childhood, Simon de Cardaillac was particularly close to Antoine Tudal, known as Antek, the son Jeannine Guillou had with Olek Teslar. They were born one year apart and grew up together, even living under the same roof on several occasions. In particular, Antoine Tudal spent the terrible winter of 1946, the one that took his mother’s life, with the Cardaillacs in Saint-Gervais [1]. The lives of the two boys were particularly intertwined until they became adults. Anecdotally, they were both introduced to swimming by Nicolas de Staël, who threw them from the top of the Roba Capeo rock in Nice. Anne de Staël recounted that her father made her go through the same ordeal, which terrified her, even though her mother was waiting in the water to catch her.[2].

[1] Laurent Greilsamer, Le Prince foudroyé, la vie de Nicolas de Staël, Fayard, 1998, p.156

[2] Interview with Anne de Staël, 11 December 2023

“In Nice, Staël had taken Antek and his friend Simon de Cardaillac to the Roba Capeo rock overlooking the sea. He had undressed, asked the children to do the same, and thrown Antek into the waves. Simon, who had refused to undress, was backing away when Staël grabbed him and threw him into the sea. Tiny Antek floated and swam like a puppy; Simon, on the other hand, was beginning to sink. Staël then dove in to help the two kids, pushing them toward the shore and concluding: “You see, you know how to swim now!”

Laurent Greilsamer, Le Prince foudroyé, la vie de Nicolas de Staël, Fayard, 1998, p.129

As an adult, it was largely thanks to Antoine Tudal that Simon de Cardaillac settled in Paris after studying architecture at the School of Decorative Arts in Nice.

“I went up to Paris, invited by a writer friend [Antoine Tudal] who realized that I had to paint. My life changed, began again […] Here Painting begins.”

Simon de Cardaillac, handwritten note dated 26/06/1988

In Paris, Simon visited museums and galleries, meeting people. Antoine introduced him to Georges Braque, amongst others. This led to several visits to the artist, as evidenced by several photographs.

“Georges Braque, through a friend, saw my work and encouraged me. Frequent visits to the (Old) Master, always well received, were fantastic and unforgettable moments for a young painter.”

Simon de Cardaillac, handwritten note dated 26/06/1988

It was Georges Braque in particular who encouraged Simon de Cardaillac to exhibit [3] in 1956 at the 11th Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, held at the Beaux-Arts in Paris (from 29 June to 5 August 1956), alongside renowned artists such as Pierre Alechinsky, Jean Arp, Sonia Delaunay and Hans Hartung. He would later form a friendship with Alechinsky and Hartung.

During these visits to Braque, Simon began a close friendship with Mariette Lachaud, Georges Braque’s assistant, an author and photography enthusiast.

[3] Chris Evers Gallery, Hus for Nutidskunst, Klampenborg, 07/1988 and Simon de Cardaillac, handwritten note of 26/06/1988

By this time, Antoine Tudal had already published several works, including Souspente (1945), a collection of poems written at the age of 12, when he was punished and forced by his parents to live in an attic for six months. His poems were very well received and illustrated by Georges Braque. This event encouraged Antoine Tudal to continue writing. He suggested that Simon de Cardaillac create the engravings for a collection entitled Simagrées.

“At the age of twenty-three, he [Antoine Tudal] decided to bring this manuscript, entitled Tempo, to a publisher, and then brought another, entitled Simagrées, which would soon be published with etchings by a painter the same age as him, Simon de Cardaillac.”

Antoine Tudal, Tempo, Librairie Gallimard, 1955, p.3

On this occasion, Simon showed his paintings to de Staël, and he encouraged him to engrave them.

“He [Nicolas de Staël] went to Sèvres to see Antoine Tudal and Simon de Cardaillac. Simon began to paint. He looked at his black, white and grey washes, his attempts at comic strips, and encouraged him: ‘Whatever you do, you have to do it well.’”

Laurent Greilsamer, Le Prince foudroyé, la vie de Nicolas de Staël, Fayard, 1998, p.263

Confident in Simon’s efforts, de Staël recommended him to Johnny Friedlaender, who had opened an engraving studio in 1949, visited by the greatest artists of the Ecole de Paris, including Maria Helena Vieira da Silva and Zao Wou-Ki.

“I was working on a project to illustrate a poetic text. Nicolas de Staël encouraged me to engrave my illustrations and recommended I work in Johnny Friedlaender’s studio. I began learning copperplate engraving.”

Simon de Cardaillac, handwritten note dated 26/06/1988

“In 1956, I took part in the “Comparisons” and “Réalités Nouvelles” art salons. Then came the Algerian War, and I was called up for military service, exposed to different light and human experiences, with no room for painting under the sun and in the white dust. Back in Paris, I had to recover from the nightmares, but I quickly started painting again. A Belgian collector was interested in my paintings. Some money to work with. American collectors arrived later. Everything was going well. I made a living from my painting.”

Simon de Cardaillac, handwritten note dated 26/06/1988

After being drafted into the army during the Algerian War, Simon de Cardaillac began a period of intense creativity and started to make a name for himself. At that time, American gallery owners and collectors played a decisive role in the art market. Many of them became interested in Simon de Cardaillac’s work. One of the first to spot his talent was the renowned photographer Irving Penn. In 1966, he asked him to send him a representative sample of his works to show to the abstract expressionist painter Sidney Gross, an art teacher at the Art Students League of New York since 1960, “very well known in New York and [who] has an excellent reputation.” Sidney Gross took an interest in Simon de Cardaillac’s work and visited in person galleries that might be exhibiting his works.

“He believes there would be maybe five or six galleries that might be interested in your work, […] he said he was interested in your work enough to go and show them him/self.”*

Retranscription non corrigée d’une lettre en français d’Irving Penn du 28 mars 1966

Furthermore, a letter from Irving Penn dated 13 June 1966, tells us that Peter Findlay of Findlay Galleries was also interested in Simon de Cardaillac’s work.

“Please contact Peter Findlay of Findlay galleries interested in your paintings at hotel de la Tremoille Paris greetings Penn”

Télégramme d’Irving Penn, le 13-6-66

The gallery was then exhibiting internationally renowned artists such as Fernand Léger, Edward Hopper, Le Phô, Bernard Buffet, Frank Stella and Roberto Matta.

In a telegram dated 25 June 1966, Irving Penn this time referred to a Palm Springs gallery planning to exhibit Simon de Cardaillac:

“The people who are coming to select paintings for their gallery in Palm Springs (California) are Mr. and Mrs. Linsk – Kristofer will call you if they arrive in my ‘unconsciousness'”

Uncorrected transcription of a letter in French from Irving Penn dated 25 June 1966

Furthermore, works by Simon de Cardaillac can be found in major American collections at the same time, such as that of Helena Rubinstein. The latter owned a 1960 painting entitled Le plan de soleils, representing an “Abstraction in tones of grey, green and white” [1]. Simon de Cardaillac most likely knew Helena Rubinstein, as he kept in his personal documents a 1960 photo of Georges Braque, Marcelle Lapré and Helena Rubinstein in Braque’s studio. This photo also completes a series of photos of the same format found in Helena Rubinstein’s collection.

We also know that a painting by Simon de Cardaillac was in the collection of the presenter and host Richard S. Starck, as evidenced by an exhibition organized in 1961 in his New York apartment and visited, in particular, by Hertha Wegner, curator of paintings and sculptures at the Brooklyn Museum[2].

We also know that a painting by Simon de Cardaillac was in the collection of the presenter and host Richard S. Starck, as evidenced by an exhibition organized in 1961 in his New York apartment and visited, in particular, by Hertha Wegner, curator of paintings and sculptures at the Brooklyn Museum[3]. One of his paintings can also be seen in the Cowles couple’s New York apartment, in a photograph published in volume 124 of the magazine House & Garden in 1963.

[1] The collection of Helena Rubinstein, New York, Paris and London, Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, 1966

[2] Cornell Alumni News, 15 mai 1961, vol.63, n°16, p.580

[3] Entretien avec Jeannine de Cardaillac, fille de Simon de Cardaillac, novembre 2023

However, despite a promising start on the American market, Simon de Cardaillac decided in the 1960s to make a fresh artistic start and gradually terminate his working relationships.

“I felt like I was trapped by something that was preventing me from working as I would like. I then decided to break off my commitments with everyone and start from scratch. I looked for work.”

Simon de Cardaillac, handwritten note dated 26/06/1988

In 1966, as American galleries and collectors began to take an interest in his painting, Simon de Cardaillac, after a two-year hiatus, decided to return to work with Hans Hartung. Simon had already been Hans Hartung’s assistant between 1961 and 1964. He had most probably met him at the 11th Salon des Réalités Nouvelles in 1956[1], where they both exhibited. Between 1961 and 1964, and then between 1966 and 1970, Simon de Cardaillac therefore assisted Hartung in the creation of his works[2]. Everything points to him having been Anna-Eva Bergman’s assistant as well. As Hervé Coste de Champeron, the expert on Hans Hartung and Anna-Eva Bergman, reminds us, “in many documents and interviews, the assistants from different periods mainly talk about their collaboration with Hans Hartung, as they were only asked about this, but they also assisted Anna-Eva Bergman, whose creative process was as technically demanding even though her output was on a smaller scale.[3]”

[1] 11th Salon des Réalités Nouvelles Réalités, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, 29 June to 5 August 1956.

[2] Rainer Michael Mason, Hans Hartung, Catalogue raisonné of prints, p.531

[3] Email of 18/12/2023

Having trained in architecture at the Arts Décoratifs in Nice, Simon de Cardaillac notably helped Hans Hartung draw up the plans for the construction of the Champ des Oliviers (the house and studio of Hans Hartung and Anna-Eva Bergman)[1]. After this project was completed in 1971, he remained in close contact with Hartung and Bergman – as evidenced by a number of documents, including several letters, greeting cards and invitations, in which Hans Hartung and Anna-Eva Bergman expressed their friendship with Simon de Cardaillac. In 1977, six years after he stopped working for them, he again participated in the design of the portfolio Lightning Pilots the Universe, made up of three zincographs, providing Hartung with his copy of Heraclitus of Ephesus in the process.[2].

[1] Archives of the Hans Hartung and Anna-Eva Bergman Foundation, letter sent to Simon de Cardaillac on 23/10/2014

[2] Rainer Michael Mason, Hans Hartung, Catalogue raisonné of prints, p.531

In addition to the set of documents mentioned above, we hold several items attesting to the Cardaillac-Hartung-Bergman relationship, including several photographs of Simon de Cardaillac in their studio (Hartung Bergman Foundation archives). As a token of gratitude and friendship, Hans Hartung and Anna-Eva Bergman presented Simon de Cardaillac with several works. A photograph of his studio features a Hans Hartung work on the wall. Even more symbolic, Anna-Eva Bergman presented Simon de Cardaillac with painting No. 56-1962, Small Image in Silver Squares, for Christmas 1963[3]; In addition to the set of documents mentioned above, we hold several items attesting to the Cardaillac-Hartung-Bergman relationship, including several photographs of Simon de Cardaillac in their studio (Hartung Bergman Foundation archives). As a token of gratitude and friendship, Hans Hartung and Anna-Eva Bergman presented Simon de Cardaillac with several works. A photograph of his studio features a Hans Hartung work on the wall. Even more symbolic, Anna-Eva Bergman presented Simon de Cardaillac with painting No. 56-1962, Small Image in Silver Squares, for Christmas 1963.

[3] Archives of the Hans Hartung and Anna-Eva Bergman Foundation

Despite his close relationship with the Hartung-Bergman couple, Simon de Cardaillac never sought to use this relationship or his contacts to promote himself, and this remained the case until the end of his life.

“Our mutual restraint and the discretion that characterizes our relationship give me great freedom in my own work. It is best to keep personal and professional relationships separate.”

Whilst working with Hans Hartung and Anna-Eva Bergman, Simon de Cardaillac had time to devote to his own painting in a large studio in Sèvres, located above Antoine Tudal’s home. He had many visitors there, including Anne de Staël, Nicolas de Staël’s only daughter, and Jeannine Guillou, with whom he was close friends.

“We would meet in the large studio where Simon, Nicole and their children lived. It was a large art studio that was absolutely magnificent. Sometimes I would come in the evening, and they would invite me to have dinner with them. While eating dinner, Simon would quickly return to his paintings. We talked about painting, about life; he was very cultured, extremely so. The topics of our conversations were very diverse, and always very interesting.

His studio was noticeably warm: it was ideally warm. Full of soul. It had large rooms, filled with paintings that had been started, but not finished.

Simon was nothing like my brother Antek. He brought something else to the table. He was very sensitive and fascinating. I got along well with his way of thinking. His main concern was his painting. But we didn’t just talk about painting. We talked about everything. He had a very cultured mind. What touched me was that he could read books that fascinated me… We particularly liked philosophy, Nietzsche, Poetry.

Interview with Anne de Staël, 11 December 2023

Around that time, Simon de Cardaillac and Anne de Staël wrote to each other often. We have letters from Anne tinged with poetry, which reveal her admiration for Simon.

“For me, the other day, it was a joy to come and see you, to see that you were still ‘the same’. This loyalty that we hold so dear is the rarest when it is given to you – it is the loyalty to oneself. […] I saw Antek walking forward with the frozen and slightly yellowed image of the child prodigy on his face and the fear of growing old! Because, for him, it’s the opposite, he’s the one being looked at.

“For me, the other day, it was a joy to come and see you, to see that you were still ‘the same’. This loyalty that we hold so dear is the rarest when it is given to you – it is the loyalty to oneself. […] I saw Antek walking forward with the frozen and slightly yellowed image of the child prodigy on his face and the fear of growing old! Because, for him, it’s the opposite, he’s the one being looked at.

Letter from Anne de Staël to Simon de Cardaillac, 13/02/1997

In 1971, Myriam Prévot, director of the Galerie de France, asked Simon de Cardaillac to work for her. This proved to be an interesting opportunity for Simon, who saw this new position as a “field of observation” of the “art market world” and which allowed him plenty of free time to devote to his painting.

Between 1971 and 1978, he was heavily involved in the organization of several exhibitions by iconic artists of his time, such as Pierre Alechinsky (1971, 1973, 1977, 1978), Anna-Eva Bergman (1977), Christian Dotremont (1971, 1975, 1978), Hans Hartung (1971, 1974, 1977, 1979), Alfred Manessier (1975, 1978), Pierre Soulages (1972, 1974, 1977) and Zao Wou-Ki (1972, 1975).

Several documents preserved by the family bear witness to his involvement, including letters providing information on the organization of exhibitions, such as that from Alfred Manessier dated 29 April 1978: “My dear Simon, I called […] regarding the “grey canvas” and “white” panels. Perhaps we could organize them: the book lithographs on grey canvas and everything book-like […] In any case, I’m leaving tomorrow and can’t tell you more; so you do your best if we can’t have everything in a single colour and material. I have complete confidence in you on this matter. Best regards, Manessier.”

On 17 October 1978, Christian Dotremont wrote to Simon de Cardaillac :

“And as for my upcoming exhibition, I wasn’t certain until today of the works I was going to show; just yesterday, I was working for this exhibition, writing and painting logograms.

Pierre Alechinsky gave me the dimensions of the windows you have. I had already designed a larger diptych. My choice of logograms to exhibit, my final, most recent choice, includes this diptych.”

Christian Dotremont, letter to Simon de Cardaillac, 17 October 1978

Alfred Manessier, Christian Dotremont and Pierre Alechinsky had in fact exhibited in the same year, 1978, at the Galerie de France. Simon de Cardaillac became friends with some of these artists, including Alechinsky. He was invited to several of his openings, including his exhibition at the FIAC, at the Maeght Lelong stand, on the occasion of his birthday.

For several years, he remained in contact with Alechinsky, who regularly sent him cards and, in particular, dedicated his copy of Maint Corps des Chambres to him with this mysterious annotation: “for Simon / who saves the little boats / lost in the Indian ink / his friend / Pierre / 4 December 1982.”

In addition to the exhibitions previously mentioned in the section on American collectors, Simon de Cardaillac exhibited several times throughout his career. After the 1956 exhibitions at the Salons Comparaisons and Réalités Nouvelles, his art was presented in a solo exhibition held at the Centre International J.-A. Maydieu in Paris from 20 February to 13 March 1971. Later on, he took part in the exhibition Abstraction Vivante, organized by Gilles Plazy at the Galerie de l’Esplanade de La Défense, from December 1976 to January 1977. The following year, he exhibited at the Mantua Biennale. In 1980, he was invited to take part in the exhibition Boomerang at the Abbey of Saint-Savin sur Gartempe, alongside Pierre Alechinsky, Karel Appel and Asger Jorn. In 1980, he was also one of three artists who exhibited at the Centre National des Arts Graphiques in Paris on the plateau Beaubourg, with Jean Clerté and Daniel Humair.

In 1981, he exhibited on the theme of “Music and Painting” accompanied by Jean-Pierre Rampal on the flute and Robert Veyron-Lacroix on the harpsichord, for the Amis de la Musique de Rueil-Malmaison. In 1984, he participated in a group exhibition around Claude Confortès’s play, Les Argileux, at the Esquisse gallery in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. Finally, his last known solo exhibition was organized in Denmark, near Copenhagen, in 1988, on the occasion of the Franco-Danish cultural year. It took place in Klampenborg in the Chris Evers gallery, and also in France, in Jean Perret’s Style Marque gallery in Paris. The theme of this exhibition was “One Painter, One Brand” and was sponsored by the Danish Carlsberg group, resulting in a series of works centred around the Carlsberg brand, as we will discuss further in this second part devoted to the work of Simon de Cardaillac.

« You see, I left your new studio thinking: what’s so familiar about this studio? Everything is different, yet everything is the same! Ephemeral, precarious, lasting! »

— Interview with Anne de Staël, 11 December 2023

Simon de Cardaillac was very interested in literature and philosophy. He was particularly interested in Nietzsche, and his familiarity with the German philosopher’s thought gives us an insight into his work. Nietzsche perceived art as an antidote to nihilism, to the belief that life is devoid of meaning and value. According to Nietzsche, art was a way to give meaning to life, even in the absence of absolute truths. Indeed, for Simon de Cardaillac, art was truly essential to life, to existence, as he wrote on several occasions:

“These events in life, the things, the breaks, the things we don’t talk about, have never distracted me from painting. I think they are part of it. For me, painting is above all a choice of existence.”

Simon de Cardaillac, 26 June 1988

These few sentences are fully in line with Nietzsche’s thinking on art, an art understood as a means of affirming life in the face of the suffering and absurdities of existence – an art capable of celebrating it.

These few sentences are fully in line with Nietzsche’s thinking on art, an art understood as a means of affirming life in the face of the suffering and absurdities of existence – an art capable of celebrating it.

Letter from Anne de Staël to Simon de Cardaillac.

Throughout his life, art was Simon de Cardaillac’s “great stimulus” [[2] ], and it always pushed him to act and create.

“While eating dinner, Simon would quickly return to paintings. […] He was very alive, very true, and that was wonderful; it brought me a lot, the idea of work, of concentration.”

Entretien avec Anne de Staël, le 11 décembre 2023

[2] F.W. Nietzsche, 1976, §24 :94

“Simon loved my father [Nicolas de Staël] very much, and I never had the feeling that he was copying him. He was truly searching for his inner self through personal expression. His work wasn’t about copying painters, but rather a beautiful and personal search for the truth.”

— Interview with Anne de Staël, 11 December 2023

Simon de Cardaillac’s early paintings presented at Vichy Enchères reveal his familiarity with Nicolas de Staël, with whom he grew up, and whose work shaped his sensibility. However, this influence faded relatively quickly, as Simon seemed more preoccupied with the medium and imagery of popular culture. He thus participated in the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles as early as 1956. The artists of this movement considered abstract art as a means of representing “new realities”, in other words, imperceptible realities of a conceptual or spiritual nature.

As with Simon de Cardaillac’s work, this artistic movement sought to reflect this new reality shaped by urban consumer society. In line with Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades, reality was placed centre stage in the creative process, in particular through the use of everyday objects elevated to the status of art objects.

Simon de Cardaillac’s work falls within this artistic movement, as the artist used – or “recycled” – objects from the urban, industrial and advertising worlds throughout his career. Indeed, his work was based on a deep reflection on pictorial practice and the possibilities offered by this medium.

Throughout his life, Simon de Cardaillac worked with cheap or raw materials, often found or recycled, in a similar vein to that of arte povera. Materials were often chosen for their raw appearance and their ability to evoke primitive or essential aspects of human existence.

Using collages and assemblages, he juxtaposed these different materials to create visual and tactile contrasts, exploring themes relating to industrial production and consumer society. Made from unexpensive materials, the artist’s works created a dialogue between art and the modern world, seeking to demystify the creative process and reduce art to its fundamental parts. Simon experimented with colour, texture and surface, often using simple and direct processes such as collage, assemblage, photography and engraving. Throughout his life, he rejected the idea of art as a luxury or commodity, favouring a more democratic and accessible approach, even refusing to sell his works or collaborate with dealers. When the writer and art critic Charles Juliet took an interest in his work and asked to interview him for a biography, Simon de Cardaillac declined. This reflection on the medium and imagery of popular culture led him to create a series based on the Carlsberg advertising logo. An exhibition was held near Copenhagen in 1988 at the Chris Evers gallery, and also in France, in Paris, at the Jean Perret Style Marque gallery. All the works produced then had “bottles, labels or crates of beer as motifs.”[1]

[1] Kjeld B. Nilsson, « Øl er øl, men også dansk-fransk kultur », Berlingske Tidende, Copenhague, 16 juin 1988.

“Certain brands have become so important in our imaginary museum that they are landmarks for the traveller who, in all the major cities of the world, finds their graphic design present and fluorescent. […] Carlsberg is the typical example. […] Red and white is the strongest relationship in signage. Style Marque […] wanted to pay tribute to this signature by partnering with Simon de Cardaillac in a poetic and pictorial vision of the brand. The artist went beyond the constraints of graphic design by using the brand and various elements of its environment as a palette of shapes and colours. It is an unusual but enriching angle for the imagery of the brand that demonstrates the strength of this visual signature, which, by breaking free from the strict framework of norms, finds a new evocative power without losing any of its personality.”

Jean Perret, director of Style Marque, 1988

This event was a success, as confirmed by this letter from Chris Evers: “People have shown a lot of interest in your paintings. I have actually sold all the oil paintings that I bought from you in Paris.” [1] However, some of the works that Simon de Cardaillac exhibited in Denmark were not returned to him, and he found himself unable to exhibit anything at the FIAC.

[1] Chris Evers House of Contemporary Art, letter of 1988

This question of the medium is closely linked to that of signage, another predominant theme in Simon de Cardaillac’s work. Signage, which encompasses road signs, graphic symbols, logos and other forms of standardized visual communication, was an infinite source of inspiration for the artist, who regularly incorporated elements from this imagery into his creations. By taking these familiar elements and placing them in new and surprising contexts, he enjoyed creating dialogues between different modes of visual communication and the cultural meanings conveyed by these signs. Through this process, Simon de Cardaillac invites us to take a fresh look at our environment and to question our lifestyles, often constrained by mechanical behaviour that responds to codes that are ingrained from a very early age.

This new vision of the urban world, both poetic and cynical, raises the question of freedom, as he alludes to in this poetic text:

“But let us return to our daily lives – here, a less northern country, but also a land of rain that makes us bow our heads in an ancestral and regressive way like dogs – and watch our feet move on the wet, black asphalt. […]

We read quickly, a quick, direct connection of the signal, a gaze focused on understanding the message given – red barrier, stop, danger, compulsory directional arrows. Even if your reason wants to go elsewhere, you obey the direction of the arrow faster than your disobedient reason.

The sign is there and… its signal.

No one escapes it. It is our reality, our daily life. […]

The aesthetics of our environment are becoming our permanent museum.

Is the eye beginning to function better? Are we entering the era of the gaze?

The light turns red – Stop –

If it were to read “stop everything right away! Instantly press your foot on the brake pedal”: accident… but, no. The red signal, with a brief blink of an eye, triggered everything – direct reflex – no reading.”

Simon de Cardaillac, text written in April 1988

Simon de Cardaillac thus integrated signage into his works to explore the aesthetics of the modern urban environment and play with its visual codes, challenging the viewer’s expectations and blurring the boundaries between art and everyday life. The use of signage also stemmed from his interest in Arte Povera and allowed him to create visually striking works with bold colours.

In addition to these urban signage elements, Simon de Cardaillac regularly added digital and typographic characters to his compositions. He was particularly interested in the symbolic power of numbers and collected in his workshop a lot of objects representing numbers, such as calendar pages, playing cards, loyalty points from service stations, stencils and even number stamps. He used them to make collages or to stamp numbers on his works. This fascination with numbers is also reflected in a series of greeting cards, created using mixed and engraving techniques, which he sent to his loved ones, like Anne de Staël, who commented on them in 1997:

“My dear Simon, how lovely was that 1997 in its sunny yellow ochre, that earth and the large 7 like a window open onto the passing ochre clouds and the year! All single numbers up to 9 fascinate me, but as soon as there are several, the multiplication slows down the emotion of a beautiful single number. It must be that a number embodies that “one day, one day we came into the world” and contains the entire clockwork of the world in which we lose ourselves!!/”

Letter from Anne de Staël to Simon de Cardaillac, 1997, family archive.

Simon de Cardaillac also cut out pages from newspapers for his collages or to extract individual letters from them. The use of type-font in his works served to explore the expressive possibilities of the written language and numerical symbols. By incorporating these letters and numbers, and sometimes entire sentences, Simon added different levels of interpretation and meaning to his creations, and proposed a dynamic interplay between the visual and the verbal. By deconstructing words and numbers, isolating them, fragmenting them, or combining them in unconventional ways, he examined their structure, meaning and sound. Finally, he used them to create interesting visual patterns and add a tactile dimension to the medium.

Furthermore, this fascination with characters and symbols also inspired a series of paintings, in ink or acrylic, created and engraved from the 1980s. These, and more particularly the black and white series, are evocative of the Asian calligraphy that fascinated the artist:

“Chinese or Japanese calligraphy – Ancient ideograms – Tactile hieroglyphs – Sensuality of the Gaze – Silences charged with subjectivity, liberties within the code but outside the code – The gaze illustrated and not the gaze commented on and read.”

Simon de Cardaillac, text written in April 1988

Perhaps we should have started with photography in the exploration of the work of Simon de Cardaillac. Indeed, it seems to serve as a starting point for the creation of many of his works. We have several series of photographs taken by the artist that reveal his interest in signs, urban signage and architecture. These photos have the particularity of always being highly zoomed in to focus on a particular element. For instance, when he photographs Paris, there are no visual element that actually identifies the capital, and it could be any other city. These photos mainly feature walls or panels for industrial paint and/or advertising posters that peeled off or were torn off.

They also feature tagged facades, numbers on shop windows, pedestrian crossings, red and white marking stripes, traffic arrows, architectural elements covered in garish colours, – or just asphalt… These photos, whether by their composition, patterns, or bold colours, could be mistaken for the assemblages of his paintings.

They all feature patterns, textures, plays of light and compositions that can be interpreted abstractly, and it is clear that these images are the source of many of his paintings.

Simon de Cardaillac painted with sensitivity and intuition. The spontaneity of his gesture, enhanced by vivid colours, fluid forms and dynamic compositions, attest to his singularity. In general, Simon de Cardaillac’s works are characterized by bold, contrasting colours, as well as organic, fluid forms, which denote the painter’s relationship with poetry. Part of his work is, therefore, akin to lyrical abstraction, which is not surprising given the lifelong bonds that united Simon de Cardaillac and Hans Hartung.

Don’t miss the exhibition on the rediscovery of Simon de Cardaillac organized by Vichy Enchères on 19 June 2025, and the sale of his studio collection.