À l’heure où le Brésil propose de reclasser le pernambouc en Annexe I de la CITES, Vichy Enchères souhaite s’associer aux nombreuses voix – musiciens, artisans, chercheurs et institutions – qui appellent à une protection renforcée de l’espèce, sans pour autant compromettre la pérennité de son usage culturel et artisanal.

Acteur du marché des instruments du quatuor, nous sommes quotidiennement témoins du rôle fondamental que joue le pernambouc dans la facture des archets et, plus largement, dans le patrimoine musical international. Nous avons conscience des enjeux écologiques liés à la déforestation de la forêt atlantique brésilienne et saluons les efforts engagés pour encadrer l’exploitation de cette ressource. Toutefois, le classement en Annexe I – qui reviendrait à une interdiction quasi totale de son commerce, y compris dans le cadre de pratiques réglementées – aurait des conséquences directes sur la transmission d’un savoir-faire reconnu, sans apporter de réponse structurelle aux causes majeures de la déforestation.

Plutôt que de freiner les initiatives vertueuses, nous soutenons le maintien du classement en Annexe II, accompagné d’un renforcement des contrôles, d’un soutien accru aux programmes de replantation et d’un dialogue ouvert entre les États, les artisans et les institutions culturelles. Il nous semble ainsi essentiel de maintenir un équilibre entre protection de l’espèce et continuité des pratiques artisanales et musicales, dans un cadre réglementé, responsable et durable.

Il nous semble ainsi essentiel de maintenir un équilibre entre protection de l’espèce et continuité des pratiques artisanales et musicales, dans un cadre réglementé, responsable et durable.

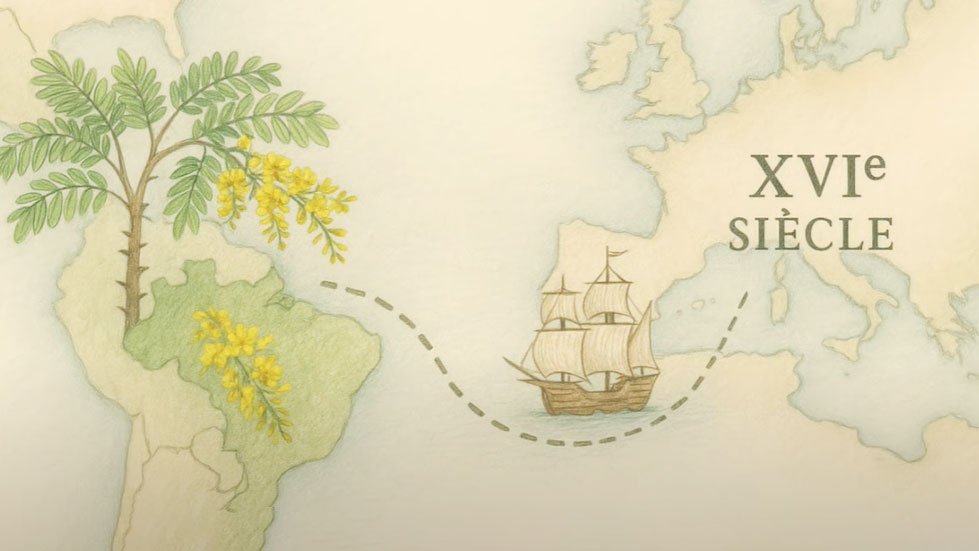

Depuis la fin du XVIIIe siècle, le pernambouc (Caesalpinia echinata) est utilisé dans la fabrication des archets d’instruments à cordes. Originaire de la forêt atlantique brésilienne (Mata Atlântica), ce bois rouge-brun, déjà exploité au XVIe siècle pour ses pigments, a été choisi par les archetiers européens pour ses qualités mécaniques exceptionnelles, alliant densité, élasticité, nervosité et pérennité.

Ces propriétés physiques en font un matériau unique. À ce jour, aucun substitut n’a permis de reproduire les qualités acoustiques du pernambouc dans le jeu instrumental. Il reste aujourd’hui le bois de référence pour la facture d’archets de haut niveau.

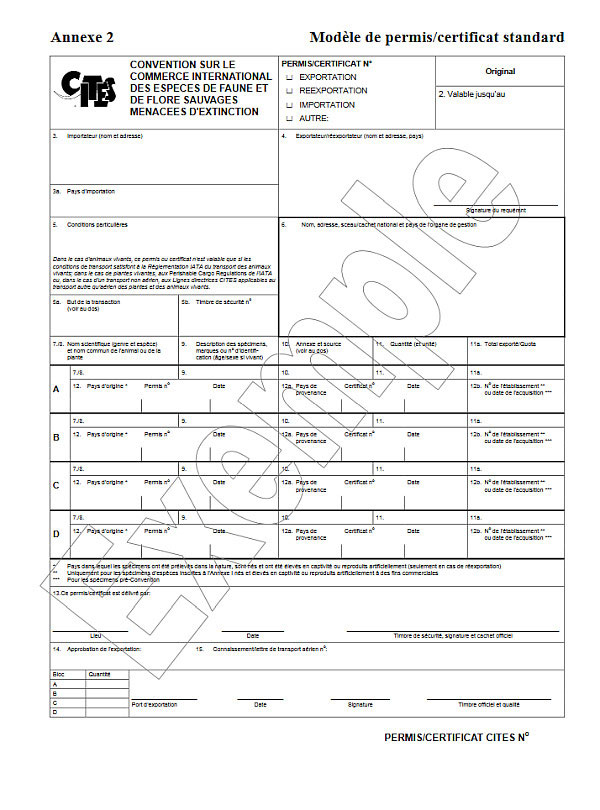

Le commerce du pernambouc est encadré depuis 2007 par la CITES (Convention sur le commerce international des espèces de faune et de flore sauvages menacées d’extinction). Inscrit en Annexe II, il fait déjà l’objet de restrictions, puisque tout transport international d’archets neufs ou anciens contenant du pernambouc doit être accompagné d’un permis.

Ce cadre réglementaire permet d’assurer la traçabilité du bois, tout en maintenant une activité artisanale fondée sur la transmission des savoir-faire, la restauration d’instruments anciens et la fabrication contemporaine.

Le Brésil, pays d’origine de l’arbre, a récemment proposé de reclasser le pernambouc en Annexe I de la CITES. Cette catégorie, qui correspond aux espèces menacées d’extinction dont le commerce est interdit sauf exception, rendrait la circulation d’archets extrêmement difficile, même à des fins culturelles, pédagogiques ou artistiques.

En pratique, chaque passage de frontière avec un archet en pernambouc nécessiterait un permis spécifique.

Les musiciens, notamment les membres d’orchestres internationaux, devraient systématiquement justifier de l’origine du bois pour chaque déplacement.

Du côté des archetiers, un tel classement entraînerait l’arrêt quasi total de la fabrication d’archets à partir de pernambouc – même issu de filières contrôlées.

L’interdiction totale du commerce du pernambouc, au lieu de renforcer la protection de l’espèce, risquerait de fragiliser un écosystème professionnel déjà très encadré. Une solution durable passerait donc par le maintien du classement en Annexe II, associé à un renforcement des contrôles sur l’origine légale du bois et la poursuite des actions de reforestation.

Le patrimoine musical et artisanal que représente la facture d’archet ne peut être dissocié de la préservation des matériaux qui le rendent possible. Il ne s’agit pas d’opposer protection de la biodiversité et transmission culturelle, mais de trouver un équilibre permettant aux deux de coexister.

La protection du pernambouc est un enjeu légitime et nécessaire. Sa replantation, la lutte contre la déforestation illégale et la préservation de la Mata Atlântica doivent rester des priorités.

Le maintien du pernambouc en Annexe II, assorti d’un encadrement renforcé et d’une coopération internationale active, apparaît aujourd’hui comme la voie la plus équilibrée. Elle permettrait de concilier la conservation de l’espèce avec la poursuite d’une activité artisanale et culturelle respectueuse des ressources naturelles.

Pour plus d’informations sur les actions de conservation et les enjeux réglementaires, consultez le site internet de l’IPCI.

In light of Brazil’s proposal to reclassify Pernambuco under CITES Appendix I, Vichy Enchères wishes to join the many voices – of musicians, makers, researchers and institutions – calling for greater protection of the species while safeguarding its use in music performance and bow making.

As an active player in the classical string instrument market, we are reminded daily of the fundamental role that Pernambuco plays in bow making and, more broadly, in the international musical landscape. We are deeply aware of the ecological issues resulting from the deforestation of the Brazilian Atlantic Forest and welcome the efforts undertaken to regulate the harvest of this resource.

However, listing this wood species under Appendix I, which would amount to a near-total ban on its trade, including in relation to activities currently subject to regulation, would have direct consequences on the future of a traditional craft, without addressing the underlying issues that are the major contributors of deforestation.

Instead of putting the brakes on worthy initiatives, we support keeping Pernambuco on Appendix II, while strengthening controls, increasing funding for replanting programmes, and fostering an open exchange between governments, makers and cultural institutions.

Therefore, we believe it is essential to maintain a balance between the protection of the species and the continuity of the craft and musical practices, within a regulated, responsible and sustainable framework.

Since the late 18th century, Pernambuco (Caesalpinia echinata) has been used in the manufacture of bows for stringed instruments. This reddish-brown wood, native to the Brazilian Atlantic Forest (Mata Atlântica), was harvested as early as the 16th century for its pigments, and was the material of choice for European bow makers due to its exceptional structural qualities, which combine density, elasticity, responsiveness and durability.

These physical properties make it a unique material. To this day, no substitute has been found which matches the acoustic qualities of Pernambuco for instrumental performance. It remains the standard material for producing bows of high quality.

The trade in Pernambuco has been regulated since 2007 by CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). This wood species is listed in CITES Appendix II and, as such, already subject to restrictions, including the fact that any international movement of new or antique bows containing Pernambuco must be accompanied by a permit.

This regulatory framework ensures the traceability of the wood, while allowing the continuation of a craft based on the transmission of traditional skills, the restoration of antique bows and the making of new ones.

The CITES classification of Pernambuco could change under a new proposal, making its trade and use impossible in the future.

Brazil, the tree’s country of origin, recently proposed moving Pernambuco to CITES Appendix I. This appendix, which lists endangered species whose trade is prohibited except in exceptional circumstances, would make the movement of bows extremely difficult, even for cultural, educational or artistic purposes.

In practice, each border crossing with a Pernambuco bow would require a specific permit.

Musicians, particularly members of international orchestras, would have to systematically provide proof of the origin of the wood for each journey they make.

For bow makers, such classification would lead to a near-total ban on making new bows from Pernambuco, even from controlled sources.

Rather than increasing the protection of the species, a total ban on the trade of Pernambuco would risk weakening an already tightly regulated professional framework. Maintaining the Appendix II listing, while reinforcing controls on the legal origin of the wood and pursuing reforestation initiatives, would constitute a more sustainable solution.

The music and craft traditions underpinned by bow making cannot be disassociated from the preservation of the materials on which it depends. It is not a matter of pitching the protection of biodiversity against the preservation of culture, but of finding a balance that allows the two to coexist.

The protection of Pernambuco is a legitimate and necessary pursuit. Its replanting, the fight against illegal deforestation and the preservation of the Mata Atlântica forest must remain priorities.