À l’occasion de la vente du samedi 7 mai 2022, Vichy Enchères vous invite à découvrir une flûte piccolo à placage d’écailles de tortue et à trois bagues en ivoire. Très rare sur le marché et dans les collections publiques, cet instrument est attribué à Johann Heitz et date du début du XVIIIème siècle. Johann Heitz est, avec Bressan, l’un des seuls facteurs à avoir réalisé des flûtes dans cette matière noble. La qualité d’exécution du piccolo, ainsi que la rareté du modèle, suggèrent un grand maître.

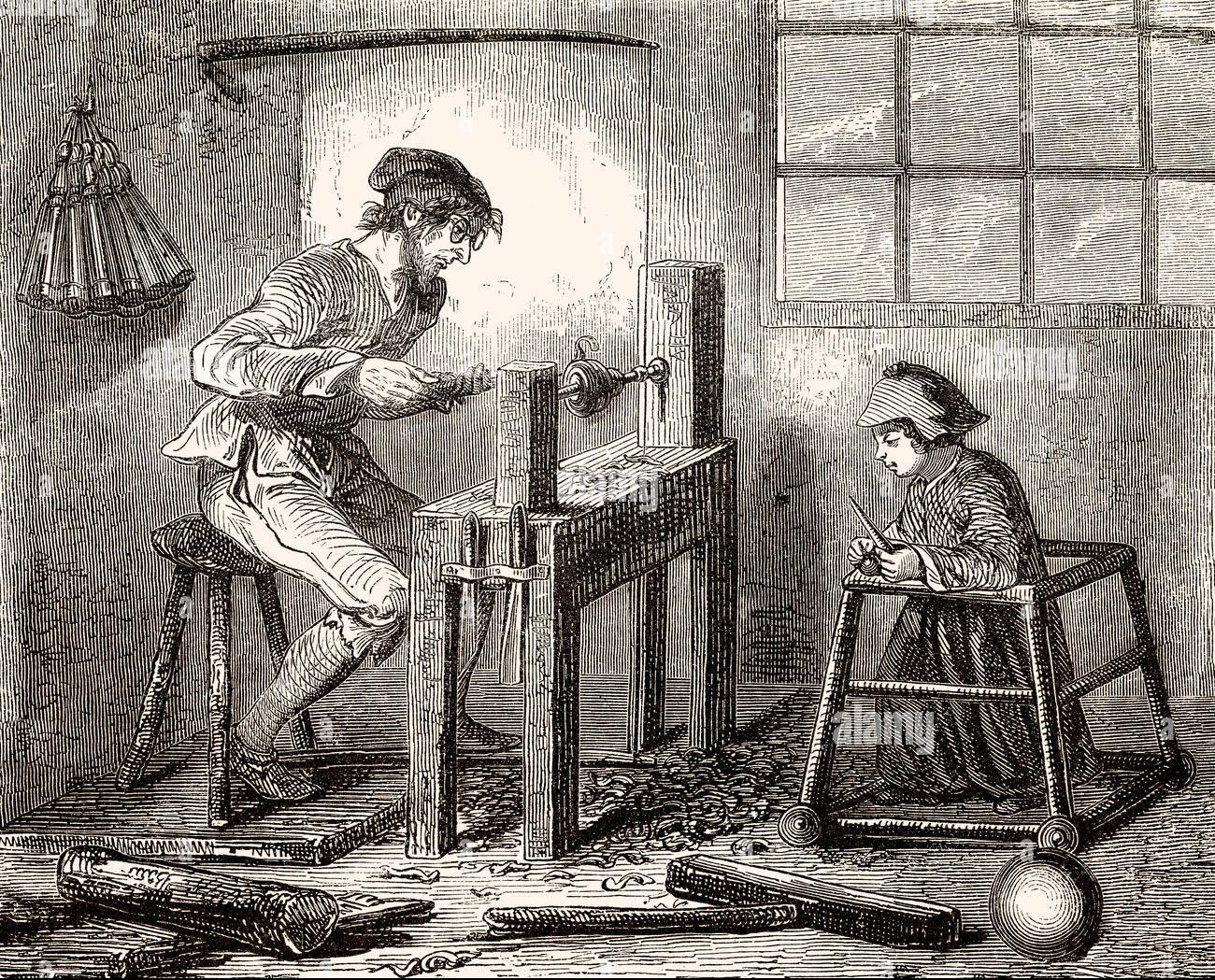

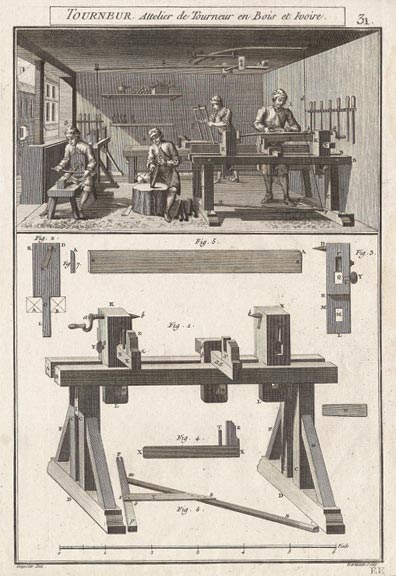

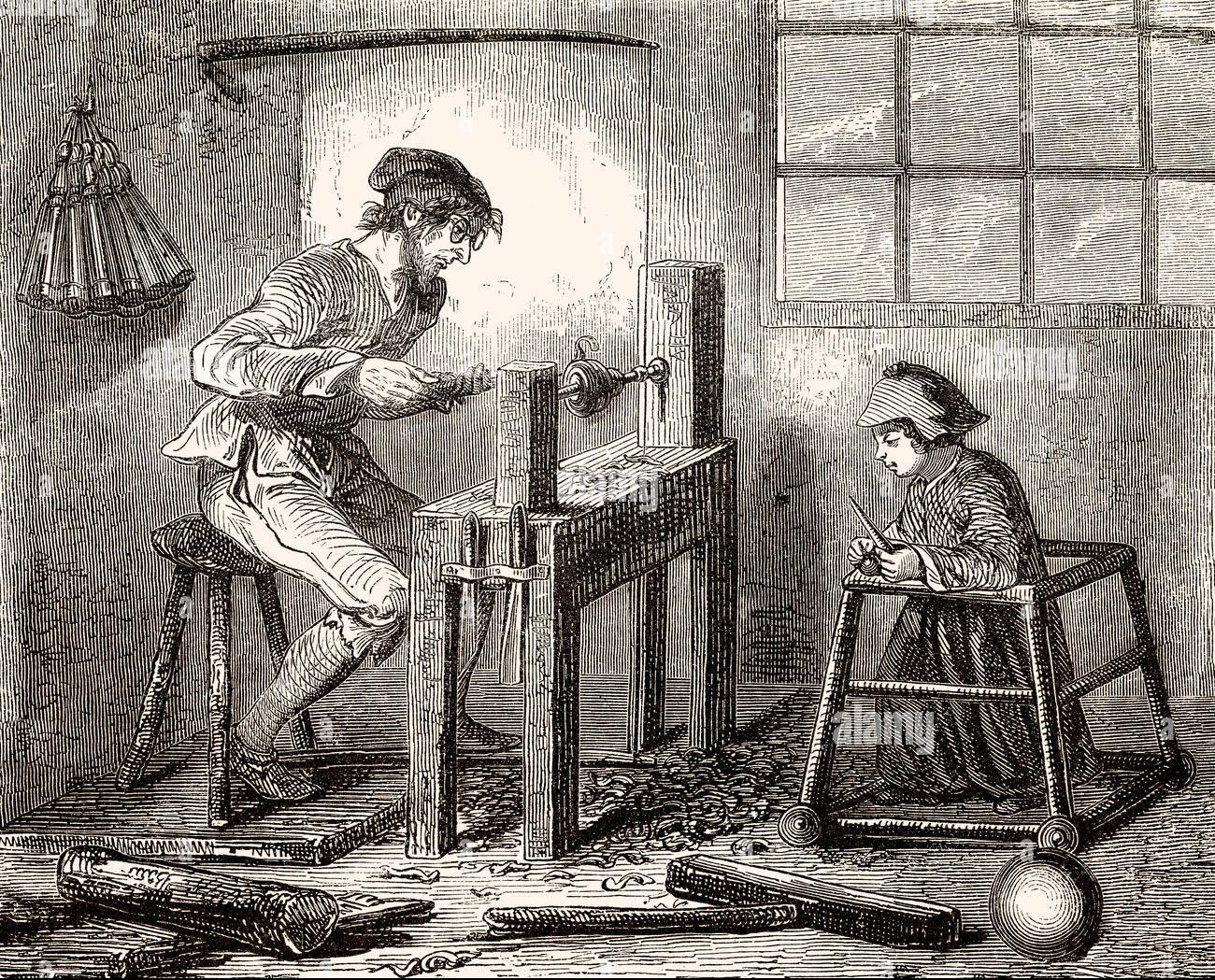

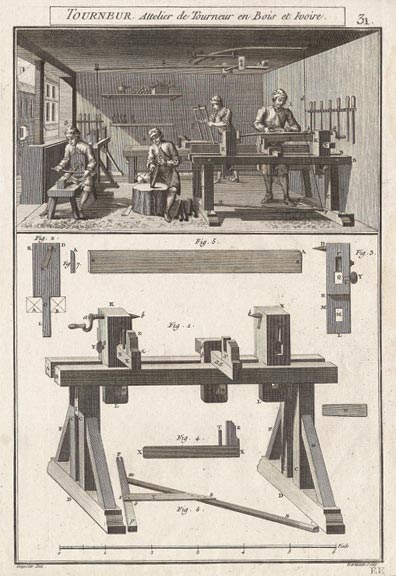

Johann Heitz ou Heytz, est né à Herrenhof en 1672, dans le duché de Saxe-Gotha-Altenbourg situé dans l’actuelle Allemagne centrale, et est mort à Berlin en 1737. Il baigne dans le milieu de la facture instrumentale très tôt, puisqu’il devient le parrain de l’enfant d’un facteur de clavecin en 1702[1]. Nous ne connaissons que peu de choses sur sa vie personnelle, si ce n’est qu’il se marie en 1703 et qu’il devient propriétaire d’une maison en 1732. Concernant sa carrière professionnelle, il est probablement actif à Berlin à partir de 1700 comme tourneur en bois et en 1713, il est mentionné dans les archives comme ébéniste. En tant que tourneur en bois, il fabrique des pièces certainement en association avec d’autres corporations et travaille aussi des matériaux rares et naturels, comme l’ivoire. Cette familiarité avec les matières nobles et vivantes explique la dextérité avec laquelle il réalise ses flûtes en écailles de tortue. L’aisance dans l’exécution du piccolo de la vente du 7 mai 2022 plaqué d’écailles est caractéristique du savoir-faire de Johann Heitz. Un savoir-faire minutieux et peu commun qui lui valut d’être nommé, en 1710, “tourneur de la cour royale et des arts, ainsi que fabricant d’instruments de musique”[2]. À partir de cette date, Johann Heitz est présent dans plusieurs cours d’Allemagne, et vraisemblablement aussi en France.

[1] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill Index, A Dictionary of Musical Wind-Instrument Makers and Inventors, Tony Bingham, London, 1993, p.170

[2] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill Index, A Dictionary of Musical Wind-Instrument Makers and Inventors, Tony Bingham, London, 1993, p.170

Johann Heitz travaille dès lors pour la cour de Berlin et fournit également la cour de Munich entre 1719 et 1721, par l’intermédiaire du facteur Pierre Naust (1660 – Paris, 1709). Compte tenu de l’étroite relation entre la cour de Berlin et celle de Köthen, il est fort probable qu’il ait aussi réalisé des instruments pour cette dernière vers 1720. À cette époque, la cour de Köthen faisait appel aux meilleurs facteurs et compositeurs, dont le plus célèbre est Johann Sebastian Bach. Celui-ci rédigea notamment ses Concertos Brandebourgeois pour la cour et les fit jouer dans la chapelle de Köthen.

Johann Heitz travailla également pour la cour de Darmstadt et pour celle de Bayreuth, comme le suggèrent les instruments provenant de la succession de la dernière margrave de Bayreuth, Sophie Charlotte de Brunswick-Lunebourg (1764-1817), qui ont été distribués à ses serviteurs méritants après sa mort, à l’instar de la flûte à bec conservée à l’Historisches Museum de Bâle[1]. Comme nous le verrons par la suite, Johann Heitz a aussi très probablement fabriqué des flûtes pour la cour de France.

[1] Martin Kirnbauer, Dieter Krickeberg, “Musikinstrumentenbau im Umkreis von Sophie Charlotte”, Sophie Charlotte und die Musik in Lietzenburg, Exposition 1987, Berlin, pp.29-60

De l’œuvre de Johann Heitz, seules quinze flûtes à bec alto sont connues, une soprano, une basse et une flûte traversière[1]. Sur ces dix-huit instruments, uniquement six ne sont pas plaqués d’écailles de tortue et trois flûtes en écailles et ivoire ne portent aucune marque[2] – à l’image du piccolo de la vente du 7 mai 2022 recouvert d’écailles de tortue et richement garni d’anneaux d’ivoire. Comme pour chacun des instruments en écailles de Johann Heitz, la facture du piccolo est extrêmement délicate et raffinée. Outre la prouesse artistique dont les flûtes de Heitz témoignent, ses instruments présentent des qualités sonores incontestables et furent prisés des musiciens et collectionneurs pour toutes ces raisons. La prédominance des modèles plaqués d’écailles de tortue est particulièrement intéressante, puisqu’elle renvoie à la technique qu’André-Charles Boulle perfectionna à la cour de Louis XIV. Les flûtes réalisées dans cette matière étant très rares, il est fort possible que Johann Heitz – facteur de cours – ait aussi travaillé pour celle de France…

[1] Phillip T. Young, 4900 Historical Woodwind Instruments, Tony Bingham, London, 1993, p.123

[2] Phillip T. Young, 4900 Historical Woodwind Instruments, Tony Bingham, London, 1993, p.123

Au regard des instruments de Johann Heitz, sa connaissance du savoir-faire français semble évidente. En effet, bien que l’écaille ait été introduite en Europe sous l’impulsion des navigateurs portugais au XVIème siècle, sa diffusion et son développement au XVIIIème siècle reposent sur le travail d’André-Charles Boulle, ébéniste de Louis XIV. Celui-ci a porté à son plus haut degré l’art du placage en marqueterie constitué d’écailles. Au temps de Heitz, le travail de l’écaille de tortue était ainsi une spécialité française et notre facteur, qui maîtrisait parfaitement cette technique, s’est ainsi probablement formé en France. Renforçant cette hypothèse, un certain nombre d’instruments réalisés au début de la carrière de Heitz sont marqués d’une fleur de lys. Selon Schmidt, ces derniers auraient été produits pour le marché français, et certainement pour la cour de France[1]. De plus, très rares sont les autres facteurs qui ont réalisé des flûtes plaquées d’écailles. Le grand nombre de flûtes de Heitz présentant un corps en buis recouvert d’écailles de tortue et des bagues en ivoire a conduit Kirnbauer & Krickeberg à émettre l’hypothèse que Pierre Jaillard – dit Peter Bressan – ait été son maître[2], puisqu’il est le seul autre facteur connu à avoir régulièrement utilisé cette technique et que Heitz semble avoir travaillé en France au début de sa carrière. Comme le démontrent plusieurs modèles dont ceux du Musée de la musique de Paris, la facture de Heitz est effectivement très proche de celle de Bressan.

[1] Manfred Hermann Schmidt, Die Blockflöten des Musikinstrumentenmuseums in München“ in „ Bericht über das VI. Symposium zu Fragen des Musikinstrumentenbaus“ Michaelstein/Blankenburg1986

[2] Martin Kirnbauer, Dieter Krickeberg, “Musikinstrumentenbau im Umkreis von Sophie Charlotte”, Sophie Charlotte und die Musik in Lietzenburg, Exposition 1987, Berlin, pp.29-60

À l’exception des instruments de Bressan et de Heitz, nous ne connaissons quasiment aucunes autres flûtes en placage d’écailles. Parmi les seules exceptions connues, on note l’existence d’une flûte à bec alto plaquée d’écailles et estampillée “*/N/HOTTETERRE”[1] – certainement pour Nicolas Hotteterre – provenant de l’ancienne collection Rosenbaum à New York, et une flûte à bec alto allemande d’un facteur non identifié, conservée au Musée de la musique de Paris.

En 1999, une flûte à bec sans marque, attribuée à Johann Heitz et provenant de la collection Rothschild, fut adjugée par Christie’s 36.700 livres.

[1] Kelly Nivison Roudabush, The Flute in transition : a comparison of extant flutes from circa 1650 to 1715, Doctor of Music, Indiana University May, 2017, p. 60

Lors de cette même vente, une autre flûte anonyme de la collection Rothschild, très proche du piccolo de la vente de Vichy Enchères, également à une clé et à placage d’écailles, fut vendue et attribuée seulement par la suite à Johann Heitz en raison de sa facture et de sa conception typiquement française, en trois parties[1].

Enfin, le Victoria & Albert Museum conserve un exceptionnel modèle probablement napolitain, daté vers 1730-1750, provenant de l’appartement parisien du compositeur Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868). La flûte piccolo de la vente du 7 mai 2022 s’ajoute à présent à cette liste d’instruments rares et, par la qualité de sa facture et de ses matériaux, renvoie à un grand nom : celui de Johann Heitz.

[1] Kelly Nivison Roudabush, The Flute in transition : a comparison of extant flutes from circa 1650 to 1715, Doctor of Music, Indiana University May, 2017, p. 60

Rendez-vous à partir du 5 mai 2022 pour admirer ce rare et remarquable instrument lors des expositions, et le 7 mai pour en suivre la vente !

As part of its auction on Saturday 7 May 2022, Vichy Enchères invites you to discover a piccolo flute with tortoiseshell veneer and three ivory rings. It is attributed to Johann Heitz and dates from the beginning of the 18th century. Instruments such as these are very scarce on the market and in public collections. Johann Heitz is, with Bressan, one of the only makers to have made flutes using this premium material. The quality of the making of the piccolo, as well as the rarity of the model, both point to the work of a great master.

Johann Heitz, or Heytz, was born in Herrenhof in 1672, in the duchy of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg located in present-day central Germany, and died in Berlin in 1737. He was immersed in the world of instrument making early on, since he became godfather to the child of a harpsichord maker in 1702[1]. We know little about his personal life, except that he married in 1703 and bought a house in 1732. Regarding his professional career, he was probably active in Berlin from 1700 as a wood turner, and in 1713 he is mentioned in archive documents as a cabinet maker. As a wood turner, he probably worked in collaboration with other corporations, and also used rare natural materials, such as ivory. This experience of working with premium materials explains the high craftsmanship of his tortoiseshell flutes. The craftsmanship of the piccolo in the sale of 7 May 2022, which is veneered with tortoiseshell, is typical of Johann Heitz. The quality of his work, meticulous in nature and not often found in other makers, earned him in 1710 the title of “turner to the royal court and to the arts, as well as manufacturer of musical instruments”[2]. From that date onwards, Johann Heitz was active in several courts in Germany, and probably also in France.

[1] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill Index, A Dictionary of Musical Wind-Instrument Makers and Inventors, Tony Bingham, London, 1993, p.170

[2] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill Index, A Dictionary of Musical Wind-Instrument Makers and Inventors, Tony Bingham, London, 1993, p.170

From then on, Johann Heitz worked for the court of Berlin and also supplied the court of Munich between 1719 and 1721, with maker Pierre Naust (1660 – Paris, 1709) acting as intermediary. Given the close relationship between the courts of Berlin and Köthen, it is very likely that he also made instruments for the latter around 1720. At that time, the court of Köthen was calling upon the best makers and composers, the most famous of which was Johann Sebastian Bach. In particular, he wrote his Brandenburg Concertos for the court and had them performed in the chapel of Köthen.

Johann Heitz also worked for the court of Darmstadt and for that of Bayreuth, as suggested by instruments from the estate of the last margrave of Bayreuth, Sophia Charlotte of Brunswick-Lüneburg (1764-1817), which were donated to her most deserving servants after her death, such as the recorder kept at the Historisches Museum in Basel [1]. As we will see later, Johann Heitz also most likely made flutes for the French court.

[1] Martin Kirnbauer, Dieter Krickeberg, “Musikinstrumentenbau im Umkreis von Sophie Charlotte”, Sophie Charlotte und die Musik in Lietzenburg, Exhibition 1987, Berlin, pp.29-60

We only know of 17 recorders (15 alto, one soprano and one bass) and one transverse flute made by Johann Heitz[1]. Of these 18 instruments, only six are not veneered with tortoiseshell, and only three recorders in tortoiseshell and ivory do not bear a maker’s mark[2] – as is the case with the piccolo in the sale of 7 May 2022, which is covered with tortoiseshell and richly ornamented with ivory rings. As with each of Johann Heitz’s tortoiseshell instruments, the piccolo’s craftsmanship is extremely meticulous and refined. In addition to their artistic qualities, Heitz’s flutes have undeniable sound qualities which were prized by musicians and collectors. The relatively large number of examples veneered with tortoiseshell that he produced is particularly interesting, since it is a technique that André-Charles Boulle perfected at the court of Louis XIV. Considering flutes made in this material are very rare, it is quite possible that Johann Heitz – as maker to the courts – also worked for the court of France.

[1] Phillip T. Young, 4900 Historical Woodwind Instruments, Tony Bingham, London, 1993, p.123

[2] Phillip T. Young, 4900 Historical Woodwind Instruments, Tony Bingham, London, 1993, p.123

In light of Johann Heitz’s instruments, it seems clear he was well versed in French making practices. Indeed, although tortoiseshell was introduced in Europe through Portuguese navigators in the 16th century, the spread and development of its use in the 18th century can be traced to the work of André-Charles Boulle, cabinetmaker to Louis XIV. He perfected the art of marquetry using tortoiseshell. In Heitz’s time, tortoiseshell work was a French speciality, and it is likely he learned his trade in France, which would explain why he perfectly mastered this technique. The fact that a number of instruments made early in Heitz’s career are stamped with a fleur-de-lis motif reinforces this theory. According to Schmidt, these would have been produced for the French market, most probably the French court[1]. Moreover, very few other makers made tortoiseshell-veneered flutes. The large number of Heitz flutes in boxwood with tortoiseshell veneer and ivory rings led Kirnbauer & Krickeberg to put forward the theory that Pierre Jaillard – also known as Peter Bressan – was his master[2], since he is the only other known maker to have regularly used this technique, and since Heitz seems to have worked in France at the beginning of his career. As shown by several examples, including those in the Musee de la musique de Paris, Heitz’s craftsmanship is indeed very close to that of Bressan.

[1] Manfred Hermann Schmidt, Die Blockflöten des Musikinstrumentenmuseums in München“ in „ Bericht über das VI. Symposium zu Fragen des Musikinstrumentenbaus“ Michaelstein/Blankenburg 1986

[2] Martin Kirnbauer, Dieter Krickeberg, “Musikinstrumentenbau im Umkreis von Sophie Charlotte”, Sophie Charlotte und die Musik in Lietzenburg, Exhibition 1987, Berlin, pp.29-60

With the exception of instruments by Bressan and Heitz, very few tortoiseshell-veneer flutes are known. Amongst these, there is an alto recorder veneered with tortoiseshell and stamped “*/N/HOTTETERRE”[1] – probably by Nicolas Hotteterre – from the former Rosenbaum collection in New York , and a German alto recorder by an unknown maker, kept at the Musee de la musique de Paris.

In 1999, an unstamped recorder, attributed to Johann Heitz and coming from the Rothschild collection, sold at Christie’s for £36,700.

[1] Kelly Nivison Roudabush, The Flute in transition: a comparison of extant flutes from circa 1650 to 1715, Doctor of Music, Indiana University May, 2017, p. 60

During the same sale, another anonymous flute from the Rothschild collection, very similar to the piccolo in the Vichy Auction sale, also with one key and veneered in tortoiseshell, was sold and only subsequently attributed to Johann Heitz because of its typically French craftsmanship and design, in three parts[1].

Finally, the Victoria & Albert Museum has an exceptional example, probably Neapolitan, dating from around 1730-1750 and originating from the Parisian flat of the composer Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868). The piccolo flute from the sale of 7 May 2022 can now be added to this list of rare instruments and, in view of the quality of its craftsmanship and its materials, can only have been the fruit of a great maker: Johann Heitz.

[1] Kelly Nivison Roudabush, The Flute in transition : a comparison of extant flutes from circa 1650 to 1715, Doctor of Music, Indiana University May, 2017, p. 60

We hope to see you from 5 May 2022 during our viewing days to admire this rare and remarkable instrument, and on 7 May to witness its sale!