La redécouverte de cette nature morte de Lubin Baugin est un réel événement pour l’histoire de l’art et la valorisation du patrimoine pictural français. Longtemps conservée dans une collection privée et révélée à Vichy Enchères, cette œuvre vient enrichir le corpus encore trop mince des natures mortes françaises connues du XVIIᵉ siècle. Elle a été vendue 550 000 € le 16 août 2025. Vichy Enchères signe ainsi le record mondial d’adjudication pour un tableau de Lubin Baugin.

Cette découverte vient porter au nombre de cinq les natures mortes signées de Lubin Baugin aujourd’hui connues. Ces œuvres, toutes réalisées dans les premières années de sa carrière, forment un ensemble d’une rare cohérence, tant sur le plan stylistique que technique.

La plus célèbre, souvent considérée comme un sommet du genre, est le fameux Dessert de gaufrettes conservé au Musée du Louvre. Ce tableau, d’une grande économie formelle, juxtapose quelques pâtisseries, un verre de vin et une fiasque sur une table recouverte d’une nappe blanche. La composition du tableau véhicule parfaitement l’art du silence et du mystère qui caractérise les natures mortes de Baugin.

Le Musée du Louvre conserve également la Nature morte à l’échiquier, dont le foisonnement des éléments représentés contraste avec la sobriété des autres natures mortes connues.

A ces deux peintures du Louvre s’ajoutent la Nature morte à la chandelle, conservée à la Galleria Spada à Rome et enfin la Nature morte à la coupe d’abricots, du Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes – probablement la plus ancienne.

Notre Nature morte aux financiers s’inscrit donc dans cette série, avec un sujet encore inédit dans son œuvre.

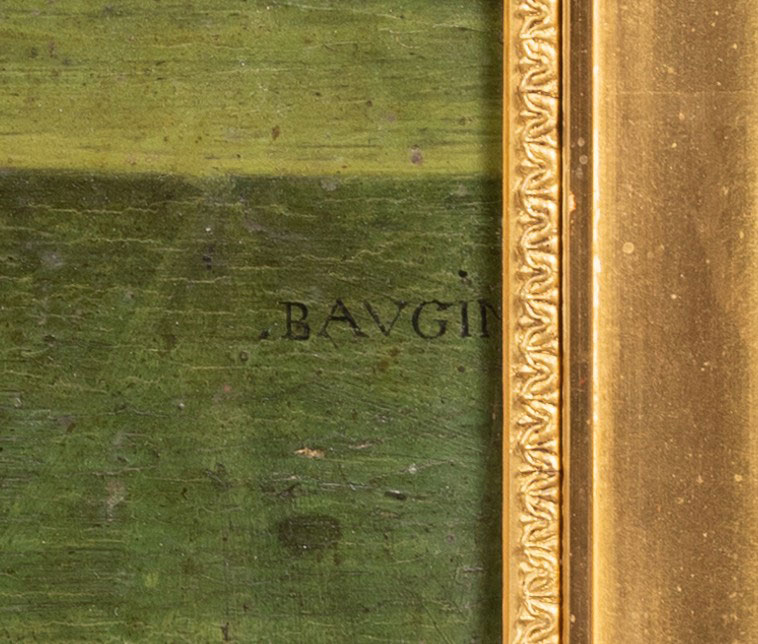

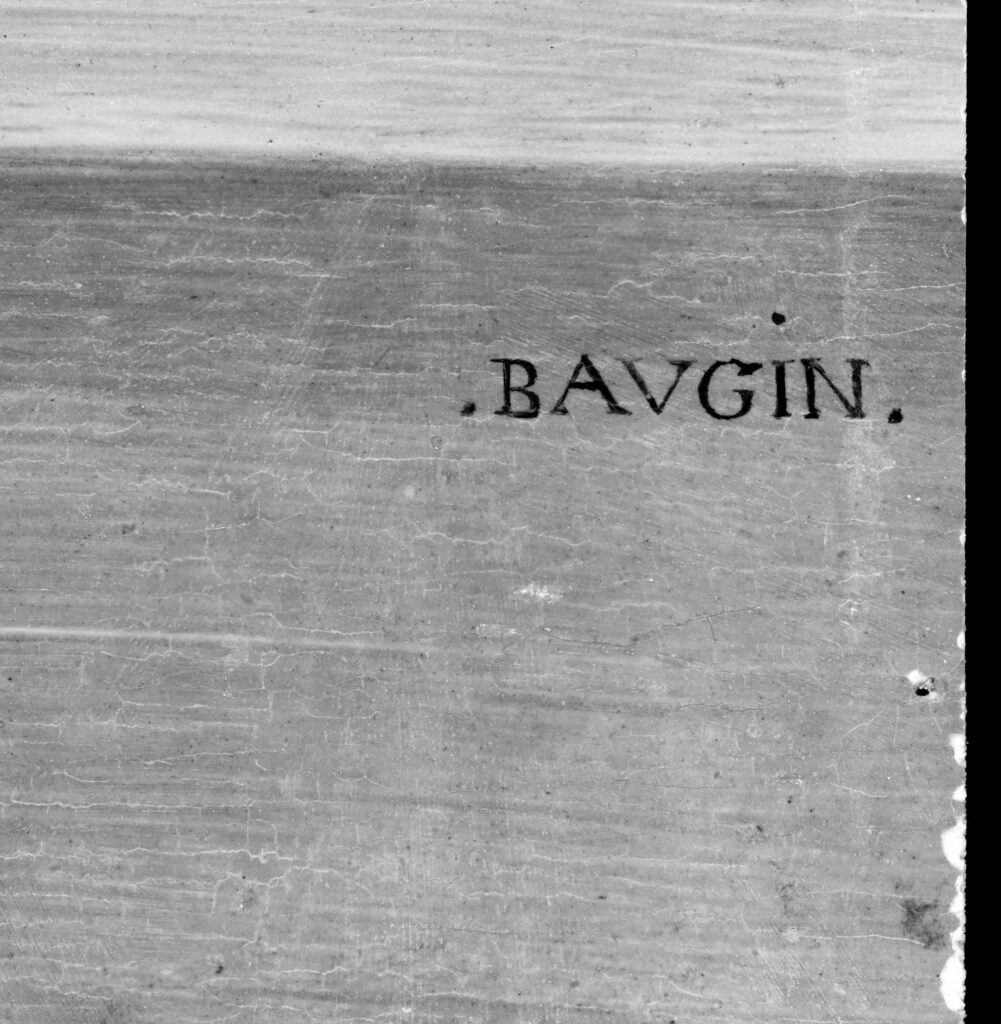

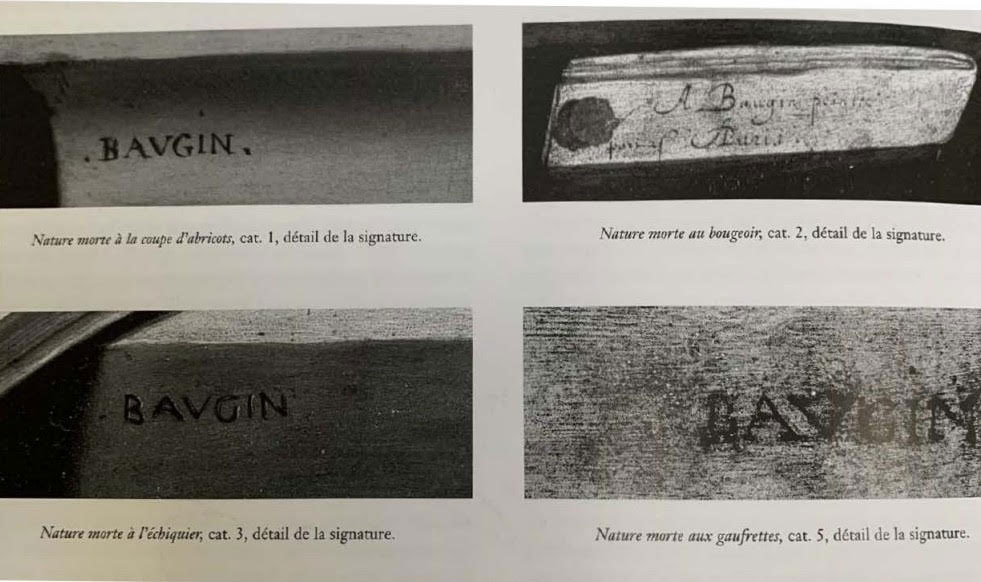

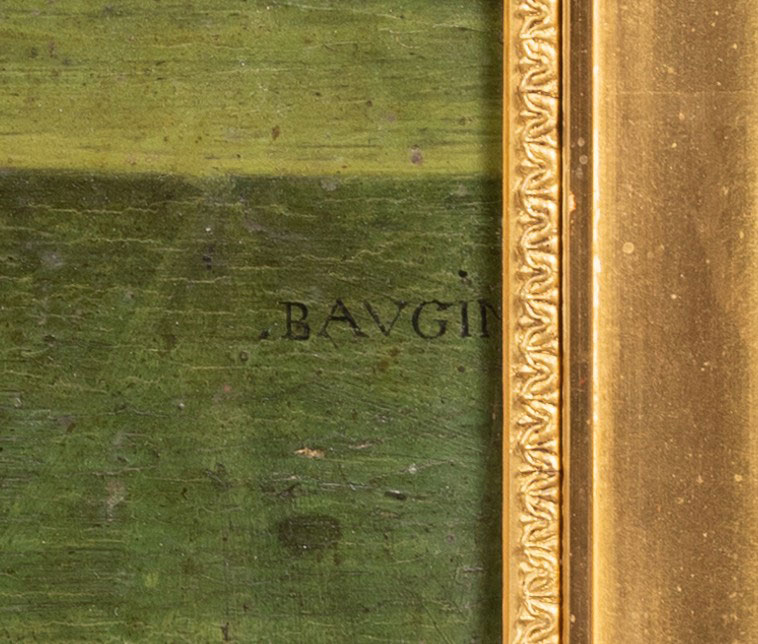

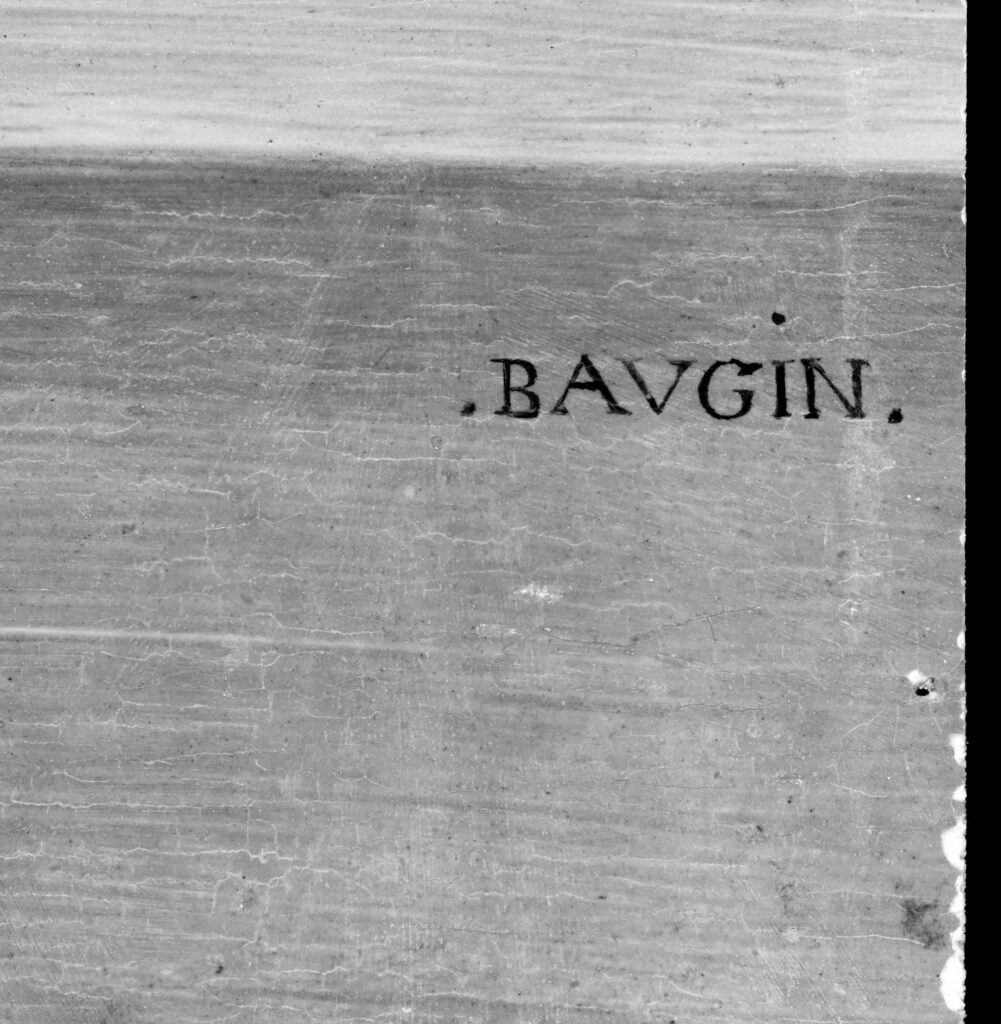

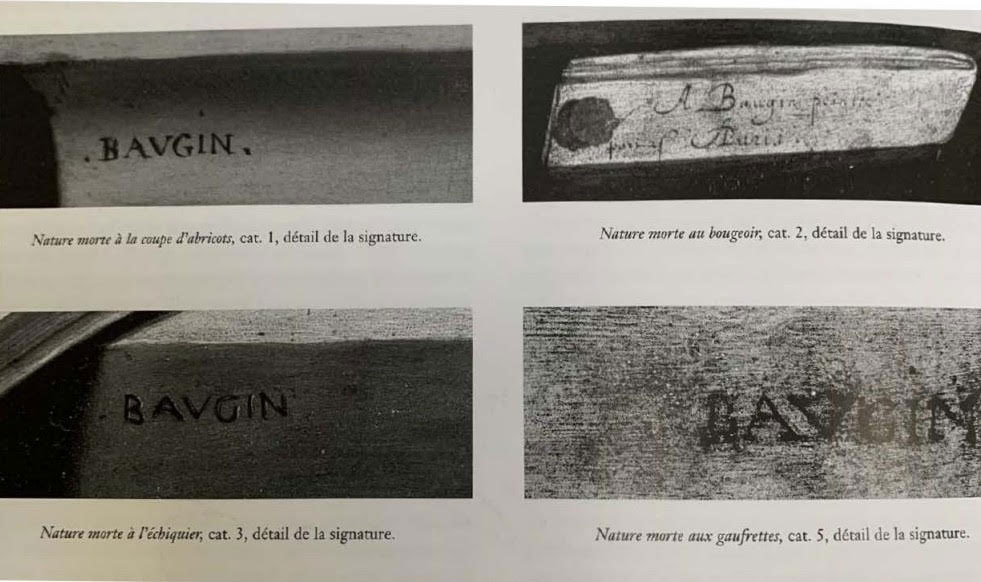

La comparaison stylistique entre cette œuvre inédite et les quatre autres natures mortes connues de Baugin est sans équivoque. On retrouve les constantes habituelles, à savoir une palette réduite, une composition ordonnée, une vaisselle sobre, un éclairage tamisé, et la signature en capitales “BAVGIN”.

L’artiste utilise des fonds sombres qui mettent en valeur les objets et modèlent subtilement leurs contours. La palette – dominée par les ocres, bruns dorés, gris-verts et blancs crayeux – vient parfaire au caractère intimiste de l’œuvre.

La disposition des objets est proche de celle du Dessert de gaufrettes. On retrouve le même verre de type hollandais placé sur la gauche, la même assiette d’étain projetant son ombre sur la nappe blanche, et un mur de pierre marquant un angle à l’arrière-plan.

Ces similitudes, renforcées par une exécution identique des effets de textures, ne peuvent qu’être l’œuvre de Lubin Baugin et inscrivent cette cinquième nature morte dans la série qu’il réalise certainement au début des années 1630.

En effet, il est très probable que toutes aient été peintes à Paris durant les premières années de sa carrière, avant son départ pour l’Italie en 1632.

Cette découverte vient également confirmer l’audace en matière de composition dont faisait preuve Lubin Baugin. On observe, en effet, que notre Nature morte aux financiers présente un couteau et une assiette qui dépassent sensiblement du bord de la table. Cette composition audacieuse donne à la scène plus de profondeur, tout en introduisant une forme d’équilibre instable, venant rompre avec l’apparente sobriété de l’ensemble. Lorsque l’on constate ceci, notre première impression – qui était celle d’une composition ordonnée, voire sévère – est supplantée par celle d’originalité et de modernisme.

Ce procédé de composition n’est pas propre à la Nature morte aux financiers mais, au contraire, vient l’inscrire davantage dans la série de natures mortes connues de Baugin. C’est ainsi le cas de la Nature morte à la chandelle (vers 1630, Galleria Spada, Rome), qui présente des lettres dépassant également du bord de la table. En outre, dans le célèbre Dessert de gaufrettes du Musée du Louvre, (vers 1630-1635), une assiette similaire avance audacieusement au-delà du plan de la table.

Enfin, dans la Nature morte à l’échiquier également conservée au Louvre, c’est presque tous les éléments qui semblent prêts à s’échapper de la table – le livre de partitions, la mandoline et l’échiquier, accentuant l’illusion de profondeur.

Cette manière de rompre la frontalité de la composition, très rare en France à cette époque, préfigure certains effets que l’on retrouvera un siècle plus tard chez Chardin et n’est pas sans rappeler les expérimentations d’artistes flamands ou hollandais, tels que Willem Claesz Heda ou Pieter Claesz, qui jouaient eux aussi sur ces effets de surplomb.

Chez Baugin, cette tension entre l’ordre et le déséquilibre confère à l’ensemble une audace et une originalité qui soulignent une fois de plus l’étonnante modernité de ce peintre.

Pour l’œil contemporain, les mets représentés dans cette nature morte de Lubin Baugin peuvent sembler énigmatiques, voire austères. Pourtant, pour un spectateur du XVIIᵉ siècle, cette peinture évoquait un véritable art de vivre et un luxe discret symbolisant la puissance et le raffinement.

Baugin a en effet placé sur la table les entremets les plus prisés de son temps, servis à la fin du repas ou entre les plats, et réservés à l’élite[1].

Au centre de la composition, posés sur un plat d’étain, on reconnaît des pâtisseries aux contours rectangulaires, moelleuses et légèrement bombées, qui évoquent les financiers ou, plus exactement, ce qu’on appelait alors “visitandines” – gâteaux à base de poudre d’amande, de sucre et de beurre, nés dans les couvents, en particulier celui de la Visitation. À leurs côtés, éparpillés avec soin, se trouvent des fruits secs – figues, dattes – et surtout des fragments de sucre cristallisé, reconnaissables à leur blancheur et à leur forme irrégulière.

Ce sucre, encore très coûteux au XVIIᵉ siècle, était consommé à l’état brut ou confit avec des épices, et constituait un produit de luxe dont l’usage à la table signalait la distinction sociale.

Ce répertoire d’entremets se retrouve dans plusieurs natures mortes contemporaines. On pense à la Nature morte aux noix, friandises et fleurs de Clara Peeters, datée de 1611 et conservée au Prado à Madrid, où le sucre cristallisé côtoie figues, raisins et amandes dans une coupe de faïence. On pourrait aussi mentionner la Nature morte avec pain et sucreries de Georg Flegel, peinte vers 1635 (Städel Museum, Francfort), où le sucre apparaît en bâtonnets, associé à du pain blanc et à des fruits confits, comparables à notre nature morte.

[1] Pour plus d’informations sur le sujet, voir Dominique Michel, Le dessert au XVIIeme siècle

Le terme d’entremets au XVIIᵉ siècle désigne l’ensemble des plats servis entre les mets principaux, notamment ceux de fin de repas. Il s’agit souvent de mets sucrés, servis après la viande ou le poisson, et destinés autant à ravir l’œil qu’à flatter le palais. Le sucre, alors produit rare et cher, importé des colonies, est un symbole de prestige. Le fait d’en disposer pour agrémenter des fruits, réaliser des biscuits, des dragées ou des confiseries, témoigne d’un certain luxe. Il en va de même pour les amandes, les figues et les fruits secs, qui faisaient l’objet d’un commerce spécialisé.

L’entremets s’affirme au XVIIᵉ siècle comme un moment privilégié du repas. Il se distingue du reste par sa légèreté, sa finesse, son aspect décoratif. Chez Baugin, l’entremets n’est pas présenté de manière ostentatoire. Il est réduit à quelques éléments. La présence du pain et du vin, associés aux financiers et au sucre, place la scène dans une tension entre l’ordinaire, le sacré – le symbolisme christique – et le plaisir.

Ce rapprochement n’est pas anodin. Il rappelle une double fonction de l’entremets : à la fois moment de délectation des sens et espace de méditation morale. On pourrait d’ailleurs lire dans cette nature morte une discrète vanité – le gâteau est déjà entamé, le vin également, le sucre va bientôt fondre et on croit observer, entre deux financiers sur la gauche de l’assiette principale, une pièce de monnaie. En cela, Baugin se rapproche des grands maîtres de la peinture morale, sans adopter leurs attributs symboliques explicites. On pense notamment à la Nature morte au vin et confiseries, souris et perroquet de Georg Flegel, conservée à l’Alte Pinakothek de Munich, véritable vanité composée entre autres de sucre cristallisé – attaqué par des rongeurs – et de pièces de monnaie. Baugin se distingue ici des tendances plus décoratives ou exubérantes des écoles flamandes, hollandaises ou ibériques. Ce réalisme sobre, presque silencieux, participe d’une forme de spiritualité du quotidien.

En France, la nature morte connaît au XVIIᵉ siècle un développement plus discret que dans les Flandres, les Provinces-Unies ou les royaumes ibériques. Ce statut périphérique explique la rareté des natures mortes françaises du Grand Siècle dans les collections publiques. Contrairement aux écoles flamandes, largement représentées dans les musées européens, la production française reste limitée et souvent dispersée. Cette rareté rend chaque redécouverte particulièrement significative.

En France, ce genre resta longtemps considéré comme inférieur dans la hiérarchie instaurée par l’Académie royale, dominée par la peinture d’histoire. Les peintres qui s’y consacraient, comme Louise Moillon, Sébastien Stoskopff, François Desportes ou Lubin Baugin, travaillèrent principalement pour une clientèle privée, souvent bourgeoise, et leurs œuvres échappèrent en grande partie aux grandes commandes publiques.

Cette situation explique leur rareté dans les collections nationales, mais aussi l’intérêt croissant qu’elles suscitent lorsqu’elles réapparaissent. Certaines redécouvertes récentes ont ainsi marqué le marché de l’art. En 2022, une Nature morte aux fraises de Louyse Moillon, longtemps conservée dans une collection privée, a été adjugée plus de 1,5 million d’euros et est aujourd’hui conservée au Kimbell Art Museum. En 2020, une spectaculaire Nature morte au trophée de gibier, fruits et perroquet sur fond de niche de François Desportes avait atteint 1,6 million d’euros, un record mondial, lors d’une vente publique à Bordeaux, confirmant la valeur patrimoniale de ces œuvres longtemps méconnues.

Dans ce contexte, l’apparition d’une cinquième nature morte signée de Lubin Baugin constitue un enrichissement de notre connaissance de l’histoire de l’art de cette époque.

Lubin Baugin naît à Pithiviers en 1610. Il se forme probablement dans le sillage de l’école de Fontainebleau. Après sa formation en province, il rejoint Paris et obtient en 1629 sa maîtrise à Saint-Germain-des-Prés. À cette époque, les jeunes peintres ne pouvaient réaliser de grands tableaux religieux ou décoratifs à l’intérieur de la ville, privilège réservé aux membres de la corporation des peintres et sculpteurs.

C’est donc dans ce contexte que Baugin, influencé par ses collègues flamands installés à Paris, s’essaya à la nature morte. Ce genre connaissait un grand succès auprès de la bourgeoisie parisienne et se vendait facilement dans les marchés du faubourg Saint-Germain. Mais cette production fut brève, sans doute interrompue par son voyage en Italie, et peu d’œuvres ont survécu.

En 1632, Baugin part pour l’Italie, séjourne à Rome, se marie et s’imprègne de la tradition classique – en particulier de Guido Reni – ce qui lui vaut le surnom de “petit Guide”.

De retour à Paris en 1641, il est désormais reconnu comme peintre d’histoire. Il obtient des commandes pour des églises, réalise des Vierges à l’Enfant, des retables, des allégories religieuses. Il convient notamment de signaler la présence, à quelques dizaines de kilomètres de Vichy, d’un chef-d’œuvre du genre attribué à Baugin. Il s’agit d’une grande Descente de croix, conservée dans la cathédrale de Luçon. Cette toile, longtemps ignorée, a été attribuée à Baugin par Jacques Thuillier et Pierre Rosenberg. Loin d’être une œuvre marginale, cette Descente de croix révèle la maîtrise de Baugin dans le domaine de la peinture religieuse monumentale. Il meurt en 1663 à Paris[1]. Tombé dans l’oubli au XVIIIᵉ siècle, il est redécouvert au XXᵉ siècle grâce aux recherches de Charles Sterling et Michel Faré, qui identifient ses natures mortes et défendent la singularité de son œuvre.

[1] Pour plus d’informations, voir : Lubin Baugin (vers 1610-1663), un grand maître enfin retrouvé, cat. exp., Orléans, musée des Beaux-Arts, 21 février–19 mai 2002 ; Toulouse, musée des Augustins, 8 juin–9 septembre 2002, sous la dir. de Jacques Thuillier, Annick Notter et Alain Daguerre de Hureaux, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 2002

L’historiographie a longtemps hésité à attribuer les natures mortes de Lubin Baugin au même peintre que les tableaux religieux. L’argument principal reposait sur la signature, puisque les natures mortes sont signées “BAVGIN” en lettres capitales, tandis que les tableaux d’histoire ne le sont pas. D’aucuns ont ainsi cru en l’existence de deux Baugin – un Lubin auteur des scènes sacrées, parfois nommé à tort Antoine ou Alexandre, et un auteur des natures mortes.

Cette hypothèse a été définitivement écartée par Michel Faré, qui a démontré l’unité stylistique des œuvres et la compatibilité biographique[1]. De plus, certaines œuvres religieuses de petit format portent bien la signature cursive de Lubin Baugin. Il est désormais admis qu’il s’agit d’un seul et même peintre, dont la production s’est adaptée aux circonstances – natures mortes à ses débuts ; œuvres religieuses à sa maturité.

[1] Michel Faré, Le Grand Siècle de la nature morte en France, le XVIIe siècle, Fribourg, 1974

Rendue au regard des historiens et des institutions, cette exceptionnelle nature morte éclaire le rôle pionnier de Lubin Baugin dans l’émergence de la nature morte française et vient enrichir notre connaissance restreinte de ce genre pictural durant le Grand Siècle.

The discovery of this still life by Lubin Baugin is very significant for French art history, and art history more generally. This work, which was long held in a private collection and was unveiled at Vichy Enchères, joins the still limited number of known 17th-century French still lifes. It sold for €550,000 on August 16, 2025. Vichy Enchères thus set the new world record for the sale of a painting by Lubin Baugin.

This discovery brings to five the number of still lifes by Lubin Baugin known today. These works, all produced in the early years of his career, are unusually consistent, both from a stylistic and technical point of view.

The most famous of them, which is often considered a masterpiece of the genre, is the famous Still Life with Wafer Biscuits held at the Louvre. This painting, with its very economical composition, features a few pastries, a glass of wine and a flask on a table covered with a white tablecloth. The painting’s composition perfectly conveys the art of silence and mystery that is typical of Baugin’s still lifes.

The Louvre also keeps Still Life with a Chessboard, whose many elements contrast with the sobriety of Baugin’s other known still lifes.

In addition to these two paintings in the Louvre, the series includes Still Life with Candlelight, held at the Galleria Spada in Rome, and finally Still Life with Peaches, in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Rennes, which is probably the oldest of the series.

Our Still Life with Financiers thus falls within this series, featuring a subject previously unseen in the work of this artist.

The similarity of style between this previously unseen work and Baugin’s four other known still lifes is obvious. The aspects that unite them are all there: a limited colour palette, an orderly composition, understated tableware, subdued lighting, and the signature « BAVGIN » in capital letters.

The artist used dark backgrounds to highlight the objects and subtly shape their outlines. The colour palette – dominated by ochres, golden browns, grey-greens, and chalky whites – adds to the work’s intimate character.

The arrangement of the objects is similar to that of Still Life with Wafer Biscuits. We find the same Dutch-style glass placed on the left, the same pewter plate casting its shadow on the white tablecloth, and a stone wall marking a corner in the background.

These similarities, reinforced by the identical treatment of texture, can only be the work of Lubin Baugin and place this fifth still life in the series he most probably completed in the early 1630s.

Indeed, it is very likely that all of them were painted in Paris during the early years of his career, before his departure for Italy in 1632.

This discovery also confirms the boldness of Lubin Baugin’s composition. Our Nature morte aux financiers features a knife and plate that protrude significantly beyond the edge of the table. This bold composition gives the scene greater depth, while introducing a form of unstable balance that breaks with the apparent sobriety of the whole. When we see this, our first impression – that of an ordered, even severe composition – is supplanted by that of originality and modernism.

This compositional technique is not specific to Still Life with Financiers, but rather places it more firmly within the series of still lifes known to Baugin. This is the case in Still Life by Candlelight (c. 1630, Galleria Spada, Rome), which also features letters protruding from the edge of the table. In addition, in the famous Dessert de gaufrettes in the Musée du Louvre (c. 1630-1635), a similar plate boldly juts out beyond the plane of the table. Finally, in Still Life with Chessboard, also in the Louvre, almost all the elements seem ready to escape from the table – the music book, the mandolin and the chessboard – accentuating the illusion of depth.

This way of breaking the frontal nature of the composition, which was very rare in France at the time, prefigures certain effects that would be seen a century later in Chardin, and is reminiscent of the experiments of Flemish and Dutch artists such as Willem Claesz Heda and Pieter Claesz, who also played on these overhanging effects.

In Baugin’s case, this tension between order and imbalance lends the whole a boldness and originality that once again underline the astonishing modernity of this painter.

To the contemporary eye, the dishes depicted in this still life by Lubin Baugin may seem curious, even austere. However, to the 17th-century eye, this painting evoked the true art of living and the discreet luxury symbolizing power and refinement.

Indeed, Baugin placed on the table the most sought-after desserts of his time, served at the end of the meal or between courses, and reserved for the elite [1].

At the centre of the composition, placed on a pewter platter, are soft, slightly rounded, rectangular pastries reminiscent of financiers or, more specifically, what were then called « visitandines »: cakes made with almond powder, sugar and butter, originating from convents, particularly that of the Visitation. Carefully scattered alongside them are dried fruits – figs and dates – and, above all, fragments of granulated sugar, recognizable by their whiteness and irregular shape.

This sugar, still very expensive in the 17th century, was eaten raw or candied with spices, and was a luxury item whose use at the table signalled social distinction.

This array of desserts can be found in several contemporary still lifes: for instance, in Clara Peeters’ Still Life with Nuts, Sweets and Flowers, dated 1611 and kept in the Prado in Madrid, in which crystallized sugar sits alongside figs, grapes and almonds in a glazed pottery bowl; also, in Georg Flegel’s Still Life with Bread and Sweets, painted around 1635 (Städel Museum, Frankfurt), where sugar appears in the form of sticks, and is combined with white bread and candied fruit, similar to those in our still life.

[1] Pour plus d’informations sur le sujet, voir Dominique Michel, Le dessert au XVIIeme siècle

The term “entremets” in the 17th century referred to all the dishes served between the main courses, particularly those at the end of the meal. These were often sweet dishes, served after meat or fish, and intended as much to delight the eye as to rejoice the palate. Sugar, then a rare and expensive commodity imported from the colonies, was a symbol of prestige. Its use to garnish fruit, or to make biscuits, sugared almonds and confectionery, demonstrated a certain luxury. The same was true for almonds, figs and dried fruits, which were all specialty items.

In the 17th century, the dessert established itself as an important part of a meal. It stood out from the other dishes for its lightness, refinement and decorative quality. With Baugin, the dessert is not presented ostentatiously. It is reduced to a few elements. The presence of bread and wine, which accompany the financiers and sugar, creates a tension between the ordinary, the sacred (Christian symbolism) and pleasure.

This juxtaposition is not insignificant. It recalls the dual function of the dessert: both a moment of sensory delight and a space for moral meditation. One could also read a discreet reference to vanitas in this still life: the cake is already partly consumed, so is the wine, the sugar will soon melt, and you can make out, between two financiers on the left of the main plate, a coin. In this, Baugin draws closer to the great masters of moral painting, without explicitly adopting their symbolism. It is reminiscent in particular of Georg Flegel’s Still Life with Wine and Confectionery, Mouse and Parrot, kept at the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, a true vanitas composed, amongst other things, of crystallized sugar – infested by rodents – and coins. Baugin distinguishes himself here from the more decorative or exuberant tendencies of the Flemish, Dutch or Iberian schools. His sober, almost muted, realism belongs to a form of everyday spirituality.

In France, still life experienced a more limited development in the 17th century than in Flanders, the United Provinces and the Iberian kingdoms. Its development on the peripheries explains the rarity of French still lifes from the 17th century in public collections. Unlike the Flemish schools, widely represented in European museums, works of French origin remain limited and often scattered. This rarity makes each rediscovery particularly significant.

In France, this genre was long considered inferior in the hierarchy established by the Royal Academy, which was dominated by historical paintings. The painters who devoted themselves to this genre, such as Louise Moillon, Sébastien Stoskopff, François Desportes, and Lubin Baugin, worked primarily for private, often bourgeois, clients and were rarely commissioned by major public institutions.

This context explains their rarity in national collections, but also the growing interest they generate when they reappear. Some recent rediscoveries have thus left their mark on the art market. In 2022, Still Life with Strawberries by Louyse Moillon, which was long held in a private collection, fetched over €1.5 million and is now in the possession of the Kimbell Art Museum. In 2020, the spectacular Still Life with Game Trophy, Fruit and Parrot Against a Niche by François Desportes reached a world record €1.6 million at a public sale in Bordeaux, confirming the historical significance of these long-overlooked works.

In this context, the discovery of a fifth still life by Lubin Baugin enriches our knowledge of the art history of this period.

Lubin Baugin was born in Pithiviers in 1610. He probably trained in the tradition of the Fontainebleau school. After training in the provinces, he moved to Paris and obtained his master’s degree at Saint-Germain-des-Prés in 1629. At that time, young painters were prohibited from producing large religious or decorative paintings within the city limits, as it was a privilege reserved for members of the guild of painters and sculptors.

It was in this context that Baugin, influenced by his Flemish colleagues living in Paris, started producing still lifes. This genre was very popular with the Parisian bourgeoisie and sold well in the markets of Faubourg Saint-Germain. However, the number of these works he produced was limited, probably due to his move to Italy, and few have survived.

In 1632, Baugin moved to Italy, stayed in Rome, married, and immersed himself in the classical tradition – particularly that of Guido Reni – which earned him the nickname “little Guido”.

Back in Paris in 1641, he was now considered a history painter. He received commissions for churches, creating Virgins and Child, altarpieces and religious allegories.

A few dozen kilometres from Vichy, there is a masterpiece of the genre attributed to Baugin. It is a large painting of the Descent from the Cross, kept in Luçon Cathedral. This painting, long ignored, has been attributed to Baugin by Jacques Thuillier and Pierre Rosenberg. Far from being a marginal work, this Descent from the Cross reveals Baugin’s mastery of monumental religious painting. He died in 1663 in Paris [1]. Having fallen into oblivion in the 18th century, he was rediscovered in the 20th thanks to research by Charles Sterling and Michel Faré, who authenticated his still lifes and championed the uniqueness of his work.

[1] Pour plus d’informations, voir : Lubin Baugin (vers 1610-1663), un grand maître enfin retrouvé, cat. exp., Orléans, musée des Beaux-Arts, 21 février–19 mai 2002 ; Toulouse, musée des Augustins, 8 juin–9 septembre 2002, sous la dir. de Jacques Thuillier, Annick Notter et Alain Daguerre de Hureaux, Paris, Réunion des musées nationaux, 2002

Art historians long hesitated to attribute Lubin Baugin’s still lifes to the same painter who produced the religious paintings. The main doubt laid with the signature, since the still lifes are signed « BAVGIN » in capital letters, while the history paintings are not. Therefore, some believed in the existence of two Baugins – Lubin, sometimes incorrectly named Antoine or Alexandre, who painted the sacred scenes – and another, who painted the still lifes.

This theory was definitively dismissed by Michel Faré, who demonstrated the stylistic similarities between the two types of works, and the fact that their production was consistent with the known biographical details on the artist [1]. Moreover, some small-size religious paintings do bear Lubin Baugin’s cursive signature. It is now generally accepted that all these works are by the same artist, whose work reflected his circumstances, painting still lifes in his early years and religious works in his later years.

[1] Michel Faré, Le Grand Siècle de la nature morte en France, le XVIIe siècle, Fribourg, 1974

This exceptional still life, which has been brought to the attention of historians and institutions, attests to Lubin Baugin’s pioneering role in the emergence of the French still life genre and enriches our limited knowledge of this genre during the 17th century.