Du 1er au 3 décembre 2020 se sont tenues à Vichy Enchères les ventes d’instruments de prestige. C’est en beauté que celles-ci se sont achevées le jeudi 3, par une sélection d’instruments des plus grands Maîtres – essentiellement des violons et archets – mais aussi des surprises, dont un violoncelle qui n’est pas passé inaperçu…

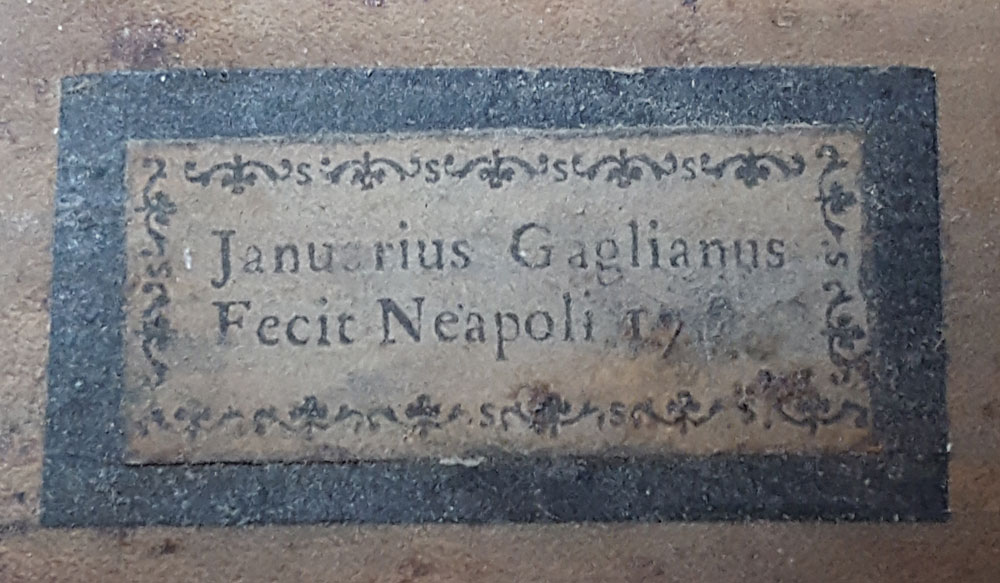

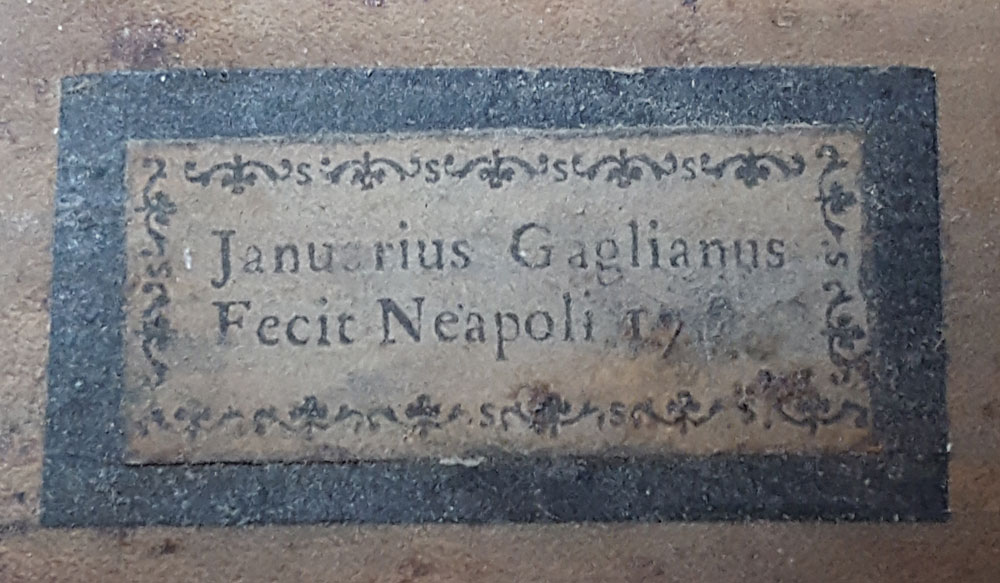

Un coup d’oeil suffit à percevoir l’intérêt de l’instrument. Un intérêt d’abord esthétique, puisqu’on est frappé par sa beauté, mais aussi historique, comme le suggère son état remarquable. Une question se pose alors : qui en est l’auteur ? L’étiquette originale, par chance sauvegardée, porte mention de “Januarius Gagliano”. Gagliano, c’est le nom de l’une des dynasties de luthiers napolitains les plus importantes des XVIIIème et XIXème siècles. La tradition de la lutherie à Naples semble dater de la fin du XVIIème siècle. L’un des tout premiers Maîtres est Mattio Poppella. Alessandro Gagliano, fondateur de la dynastie bien connue en aurait été le disciple. Cette tradition va s’ancrer de plus en plus tout au long du XVIIIème siècle. Outre les Gaglianos, d’autres dynasties vont bientôt émerger (Les Ventapane, les Vinaccia). Au sein de la famille Gagliano, Gennaro (c.1740 – c.1780), fils d’Alessandro et frère de Nicola, est considéré comme l’un des plus grands.

Son style allie à la fois finesse et élégance dans le dessin de ses modèles, précision dans la réalisation technique (la pose du filet, la découpe des ouïes sont toujours impeccables) et robustesse notamment dans la conception des voûtes de ses instruments. Les volutes aux profils élancés, le vernis légèrement sec aux teintes allant du jaune-orangé à l’orangé-brun plus soutenu sont là pour rappeler que si Gennaro sut développer un style propre à lui, son oeuvre reste tout de même très marquée par la tradition napolitaine.

Autant des détails qui font de ses instruments de véritables oeuvres d’art très prisées aujourd’hui par les musiciens et les amoureux de l’école italienne du XVIIIème siècle.

Ses violoncelles sont particulièrement appréciés des musiciens car il a su développer un modèle personnel aux qualités acoustiques indéniables.

L’école napolitaine a longtemps été considérée – à tort – comme une école de moindre importance en comparaison des écoles de Milan, de Venise et surtout de Crémone. Il est vrai que l’on peut parfois rencontrer au sein même de la dynastie Gagliano, des instruments de qualité inférieure dans leur réalisation qui étaient à n’en pas douter destinés à une clientèle de dilettanti ou de musiciens de rue. Mais il existe aussi de somptueux instruments, réalisés avec tout le savoir-faire et la maîtrise que l’on peut attendre d’un luthier qui possède son art. Ce violoncelle en est un parfait exemple, puisqu’il combine le savoir-faire de l’école napolitaine et une approche stylistique personnelle. En outre, l’influence des grands Maîtres de l’âge d’or de la lutherie italienne est ici perceptible. Nul doute que ce violoncelle ait été conçu pour un musicien exigeant ou un collectionneur important. Les bois utilisés sont de premier ordre. Le fond d’une pièce (très rare pour un violoncelle) est d’un érable légèrement moucheté à ondes très vives particulièrement séduisant.

Les zones où les ondes se font plus discrètes (au centre) ont été rehaussées à l’encre de chine. Coquetterie de l’auteur ou volonté de produire un instrument visuellement irréprochable ?La tête d’un bel érable à ondes régulières est magnifiquement sculptée. Elle est agrémentée d’un chanfrein noirci, autre détail que l’on rencontre habituellement peu à Naples et qui vient encore souligner l’importance que devait avoir le dédicataire de ce violoncelle ainsi que la volonté de l’artisan de s’employer au mieux à honorer cette commande prestigieuse. Les vernis employés habituellement par les luthiers napolitains n’avaient pas la complexité ni la richesse de teintes de ceux que l’on retrouve à Venise ou Crémone. Néanmoins, celui appliqué par Gennaro sur son violoncelle et d’une qualité irréprochable. Il est plus épais et de consistance plus souple, ce qui lui a permis de ne pas se craqueler au fur et à mesure des années. Incroyablement préservé dans sa quasi totalité, d’un orangé soutenu tirant sur le jaune d’or dans les zones légèrement dégradées…

Ce violoncelle, on l’aura compris, est d’un intérêt considérable d’un point de vue « technique » mais également artistique. À instrument exceptionnel, musicien exceptionnel. À qui pouvait-il appartenir ? La provenance peut conférer une dimension supplémentaire, cette fois-ci historique, à l’instrument en le liant à une figure de l’histoire de la musique. Dans le cas du violoncelle de Gennaro Gagliano, sa provenance est véritablement prestigieuse. Il fut, en effet, l’instrument de Sir John Barbirolli qui, avant de devenir le chef d’orchestre acclamé, avait débuté sa carrière en tant que violoncelliste. S’imaginer que Barbirolli joua avec cet instrument le concerto pour violoncelle d’Elgar sous la direction du compositeur est renversant !

L’incroyable carrière de Barbirolli en tant que chef d’orchestre l’a certainement conduit à délaisser la pratique instrumentale pour la direction. Cela pourrait expliquer le remarquable état de conservation du violoncelle (que l’on peut mesurer à la préservation presque intégrale du chanfrein noir sur la tête – fait très rare pour des instruments de cet âge). Réalisé vers 1760 (l’étiquette donne une date peu lisible), ce violoncelle, après Sir John Barbirolli, appartint à deux autres musiciens, dont un français, particulièrement soigneux.

Aujourd’hui, à qui serait destiné un tel instrument ? Sans conteste à un très bon musicien – le violoncelle étant d’une admirable qualité. Néanmoins, son intérêt historique et artistique, combiné à son remarquable état de conservation, en font une rareté, et ainsi, un objet de collection.

Né en 1899 à Londres, Giovanni Barbirolli est issu d’une famille franco-italienne. Chef d’orchestre et violoncelliste, il s’initie au violon dès l’âge de quatre ans, puis débute le violoncelle à dix ans avant d’intégrer le Trinity College of Music de Londres en 1910. Il obtient rapidement une bourse lui permettant de se former à la Royal Academy of Music de Londres, de 1912 à 1916. C’est au cours de son engagement dans l’armée, en 1917, qu’il dirige pour la première fois un ensemble instrumental. Aspirant à devenir chef d’orchestre, il participe à la fondation – à Chelsea en 1924 – de la Guild of Singers and Players Chamber Orchestra, dont il prend la tête. En 1926, The British National Opera Company l’invite à diriger son orchestre lors d’une tournée. Il continue à le diriger ponctuellement jusqu’en 1929, faisant ainsi ses preuves sur de grands classiques, tels que Madame Butterfly de Puccini. De 1929 à 1933, il est le premier chef de la Covent Garden Touring Company, qu’il délaisse pour prendre la direction du Scottish Orchestra de Glasgow, et ce jusqu’en 1936.

C’est aux États-Unis que sa carrière va réellement s’envoler, au milieu des années trente. En effet, en 1936, il succède à Arturo Toscanini, le célèbre chef d’orchestre italien, au Philharmonique de New York.

Ses concerts connaissent un tel succès que l’orchestre lui propose de devenir chef permanent. Il se mesure à des oeuvres contemporaines majeures et en assure les premières mondiales, dont celle de la Sinfonia da requiem de Britten. Il quitte son poste en 1942 et rentre en Angleterre, bien que le Los Angeles Philharmonic lui propose de devenir son chef principal.

A son retour en Europe, Barbirolli collabore avec le Hallé Orchestra de Manchester et débute un mandat qui durera jusqu’à sa mort – soit vingt-sept ans. Sa notoriété et son expertise le conduisent à diriger, parallèlement à son activité à Manchester, des orchestres aux quatre coins du monde – notamment à Berlin, Vienne et Rome. Il retourne également aux Etats-Unis et succède à Leopold Stokowski à la tête du Houston Symphony Orchestra, de 1960 à 1967.

Enfin, notons que John Barbirolli fait partie des grandes figures de l’histoire du disque, puisque des centaines de galettes ont été éditées par EMI, l’une des majors du disque de l’époque. Passionné et perfectionniste, il meurt en 1970 – quasiment derrière son pupitre – à la veille d’une répétition avec le New Philharmonia Orchestra de Londres, en vue d’une tournée au Japon. Sir John Barbirolli compte parmi les plus grands chefs d’orchestre de l’histoire, en atteste son vaste répertoire, de Schubert à Sibelius, en passant par Mahler, Corelli ou encore Stravinsky.

Un texte de Jean-Jacques RAMPAL & Jonathan MAROLLE (Maison VATELOT-RAMPAL) / Vichy Enchères

© Christophe DARBELET / Maison VATELOT-RAMPAL

From 1st to 3rd December 2020, Vichy Enchères organized its fine musical instruments auction. It ended in style on Thursday 3rd with a selection of instruments, mainly violins and bows, by the greatest masters, but also some surprises, including a cello that did not go unnoticed…

It is immediately apparent why this instrument is so interesting. Its striking beauty is the first thing that one might notice, but its interest is also historical, as hinted at by its remarkable state of preservation. The question arises: who is its maker? The original label, fortunately still present inside the instrument, reads “Januarius Gagliano”. Gagliano is the family name of one of the most important Neapolitan dynasties of violin makers in the 18th and 19th century. The beginning of the violin making tradition in Naples seems to date back to the end of the 17th century. One of its very first masters was Mattio Poppella; Alessandro Gagliano, the founder of the dynasty, is thought to have been his pupil. This tradition developed in the 18th century, and, apart from the Gaglianos, other dynasties emerged (the Ventapanes, the Vinaccias). Within the Gagliano family, Gennaro (c.1740 – c.1780), son of Alessandro and brother of Nicola, is considered to be one of the best makers.

His style combines fineness and elegance in the design of his models, and precision in the technical execution (the insertion of the purfling and cut of the f-holes is always flawless), with boldness, in particular in the design of the archings of his instruments. The scrolls, with a slender profile, and the slightly dry varnish with a tint going from a yellow-orange to a deeper orange-brown, remind us that, although Gennaro developed his own distinctive style, he was heavily influenced by the Neapolitan tradition.

All these details make his instruments true works of art, very sought after today by musicians and lovers of the 18th century Italian school alike.

His cellos are particularly prized by musicians due to the sound quality of the unique model he developed.

The Neapolitan school of violin making has long been considered, incorrectly, as a minor school in comparison with the schools of Milan and Venice, but mostly Cremona. It is true that, amongst the output of the Gagliano family, one can occasionally come across instruments of lesser quality, which were probably destined for the dilletanti or street musicians. However, there are also examples of the highest order, clearly made by makers that had a great understanding of their art and were in full command technically. This cello is a good example of the latter, as it combines the technical expertise of the Neapolitan school with a personal stylistic approach. Moreover, the influence of the great masters of the golden age of violin making can be felt here. This cello was undoubtedly made for a demanding musician or an important collector. The wood used is of the best quality. The back, in one piece (which is rare for a cello), is from slightly speckled maple with an attractive strong figure.

In the areas where the figure is more subtle (in the centre) China ink was used to recreate a stronger flame. Was it an affectation on the part of its maker or the desire to produce an instrument visually flawless? The head of handsome maple with regular figure is wonderfully carved. It is embellished by blackened chamfers, a detail that is seldom encountered in Naples and denotes the importance of the person for whom this cello was made, as well as the desire of the craftsman to work to the highest standards for this prestigious commission. The varnishes normally used by the Neapolitan violin makers did not have the complexity or richness of tint of those found on instruments from Venice or Cremona. However, the one applied by Gennaro on this cello is of indisputable quality. It is thicker and softer in its consistency, which is why it has not crackled over the years. It is incredibly well preserved on almost all the instrument, and of a deep orange turning into golden yellow in the slightly worn areas.

As previously mentioned, this cello is of considerable interest not only from a ‘technical’ standpoint but also an artistic one. An exceptional instrument calls for an exceptional musician. To whom could it have belonged? Provenance can bestow further significance, this time historical, to an instrument, by linking it with a prominent figure in the history of music. In the case of this cello by Gennaro Gagliano, its provenance is truly prestigious indeed: it was the instrument of Sir John Barbirolli, who, before becoming an acclaimed conductor, started his career as a cellist. To think that Barbirolli played on this instrument when performing the Elgar cello concerto under the direction of the composer himself is truly astounding.

The incredible career of Barbirolli as an orchestra conductor inevitably led him to neglect instrumental practice in favour of conducting. This could explain the incredible state of preservation of this cello (which is best demonstrated by the almost perfect preservation of the black paint on the scroll chamfers, something which is very rare for instruments of this age). Made in 1760 (although the date on the label is hard to read), this cello belonged to other musicians after Sir John Barbirolli, amongst them a French one who took particularly good care of it.

For whom could this cello be destined today? Without doubt a very good musician, the cello being of such outstanding quality. However, its historical and artistic significance, combined with its remarkable state of preservation, make such a cello a rare piece and, as such, a collector’s piece.

Giovanni Barbirolli was born in 1899 in London into a Franco-Italian family. The orchestra conductor and cellist started learning the violin at the tender age of four and switched to the cello aged 10, before being admitted to Trinity College of Music in London in 1910. He quickly obtained a scholarship allowing him to pursue his studies at the Royal Academy of Music in London from 1912 to 1916. It is during his time in the army, in 1917, that he conducted for the first time an instrumental ensemble. Aspiring to becoming a conductor, he took part in the creation in 1924 in Chelsea of the Guild of Singers and Players Chamber Orchestra, of which he became director. In 1926, the British National Opera Company invited him to conduct its orchestra during a tour. He continued to conduct this company from time to time until 1929, which gave him an opportunity to hone his skills on the great classics, such as Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. From 1929 to 1933, he was chief conductor of the Covent Garden Touring Company, which he then left to take the helm at the Scottish Orchestra in Glasgow, where he remained until 1936.

It was in the United States in the mid 30s that his career took off in earnest. Indeed, in 1936 he succeeded Arturo Toscanini, the famous Italian conductor, at the New York Philharmonic.

His early concerts were so successful that the orchestra offered him a permanent position. He took on major contemporary music pieces and premiered them worldwide, including Britten’s Sinfonia da Requiem. He left his position there in 1942 and returned to England, despite an offer from the Los Angeles Philharmonic to become its chief conductor.

On his return to Europe, Barbirolli collaborated with the Hallé Orchestra in Manchester, and took up a position there that he held for 20 years, until his death. In parallel with his activities in Manchester, his fame and expertise led him to several orchestras in all corners of the world – notably Berlin, Vienna and Rome. He also returned to the U.S. and succeeded Leopold Stokowski as chief conductor of the Houston Symphony Orchestra from 1960 to 1967.

Finally, we should point out that John Barbirolli is an important figure in the history of music recording, since EMI, one of the major record labels during his time, produced hundreds of his recordings. A passionate perfectionist, he died in 1970 – almost at his conductor stand – on the eve of a rehearsal with the New Philharmonia Orchestra in London, in preparation for a tour of Japan. Sir John Barbirolli is amongst the greatest conductors of our times, as his vast musical repertoire – from Schubert to Sibelius, to Malher, Corelli or Stravinsky – attests.

An article by Jean-Jacques RAMPAL & Jonathan MAROLLE (Maison VATELOT-RAMPAL) / Vichy Enchères

© Christophe DARBELET / Maison VATELOT-RAMPAL

Translation by Marc BUTTERLIN