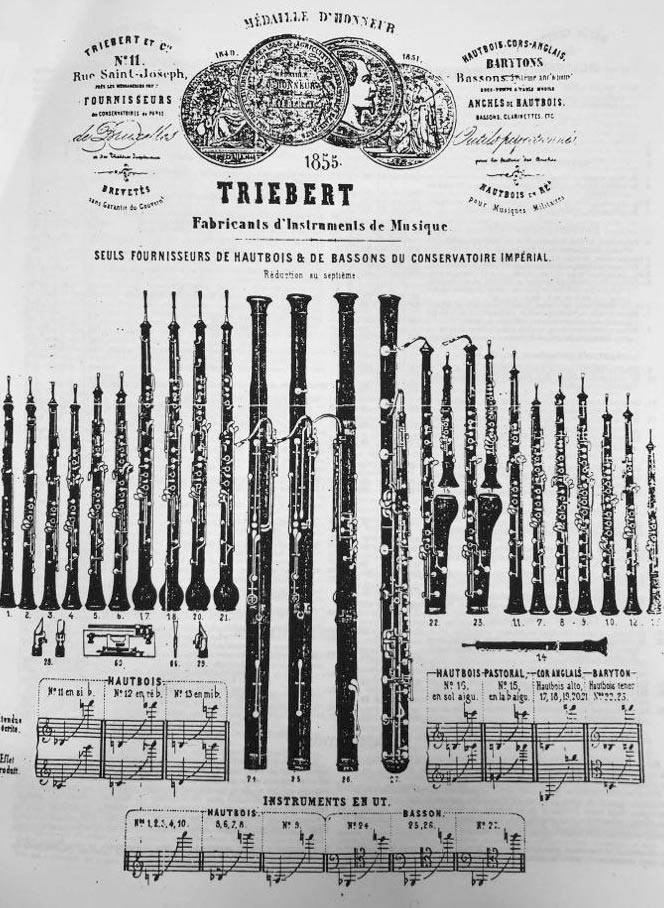

À l’occasion de la vente d’instruments à vent et à cordes pincées du 7 mai 2022, l’exceptionnel ensemble de hautbois réuni fera rejaillir l’histoire de l’instrument au XVIIIème siècle, jusqu’à son apogée au temps de Guillaume et Frédéric Triebert. À travers les figures d’éminents facteurs à l’instar de Charles Bizey, Dominique Porthaux, des Borman, Kinigsperger, Cramer, et bien sûr des Triebert, c’est une partie de l’histoire de la facture européenne du hautbois qui se dessinera sous vos yeux… Cette réunion d’instruments vous donnera aussi l’opportunité de découvrir un superbe baryton de Frédéric Triebert, dont le modèle apparaissait sur le catalogue des instruments de la Maison en 1855…

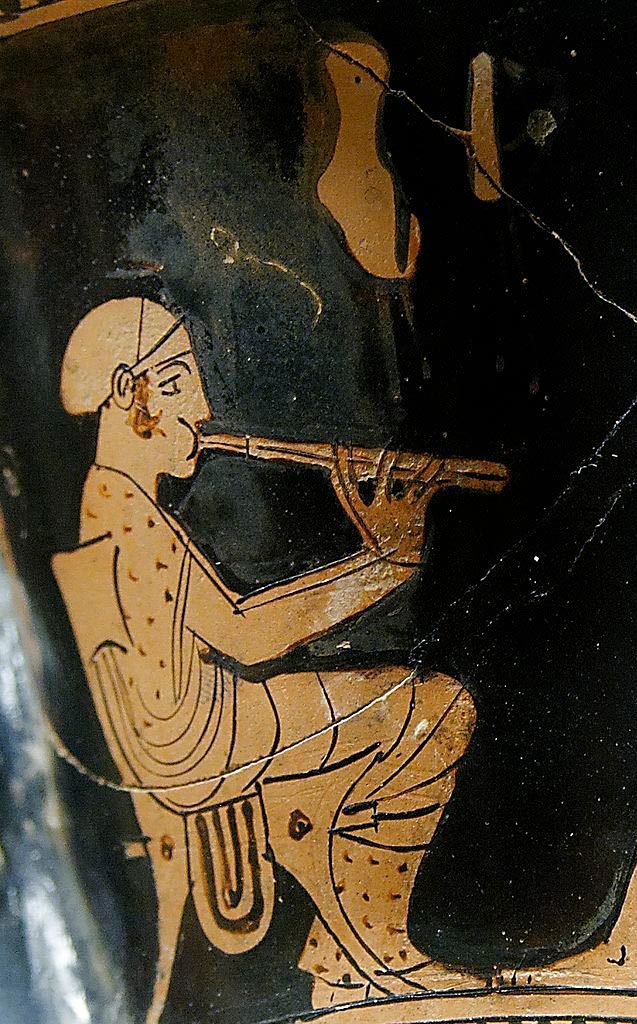

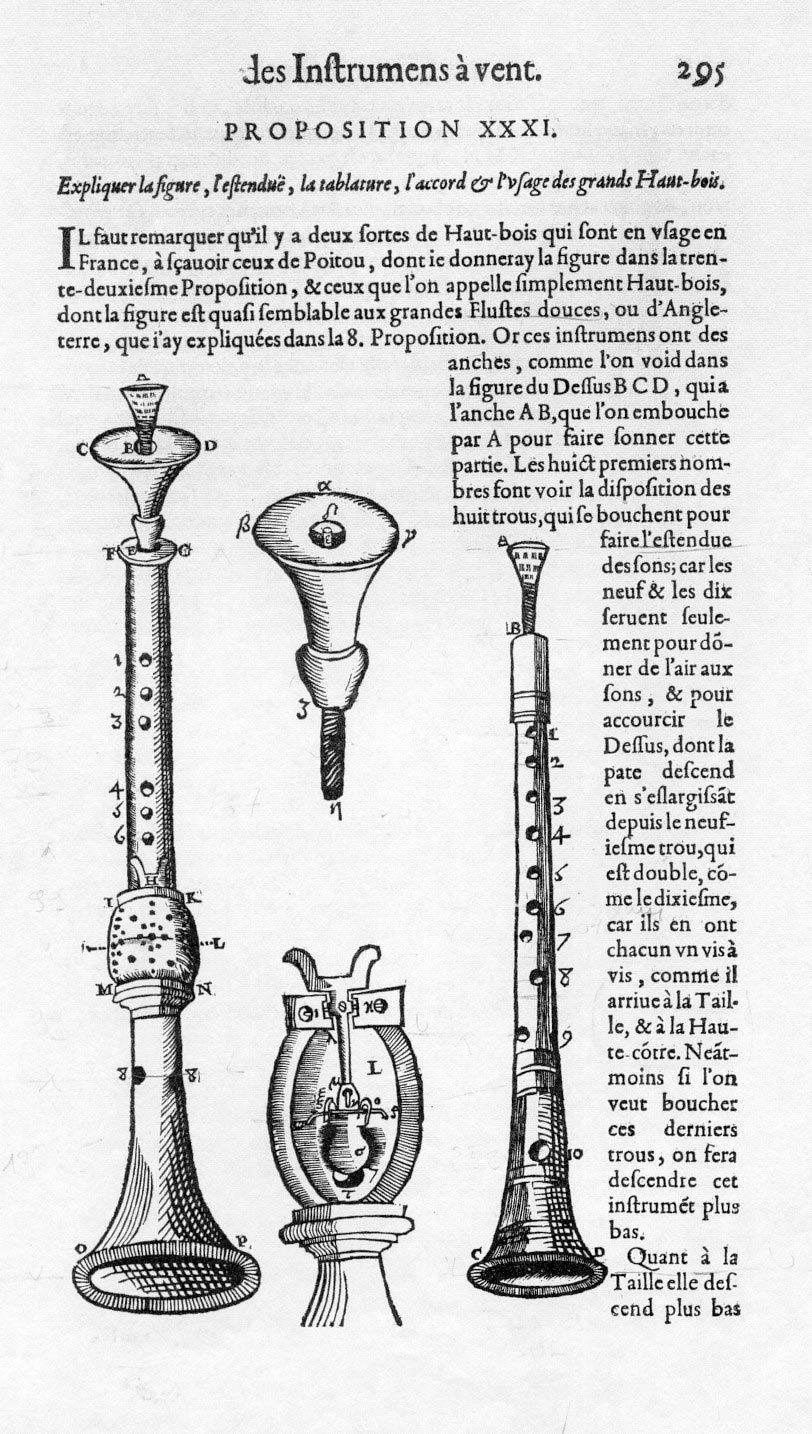

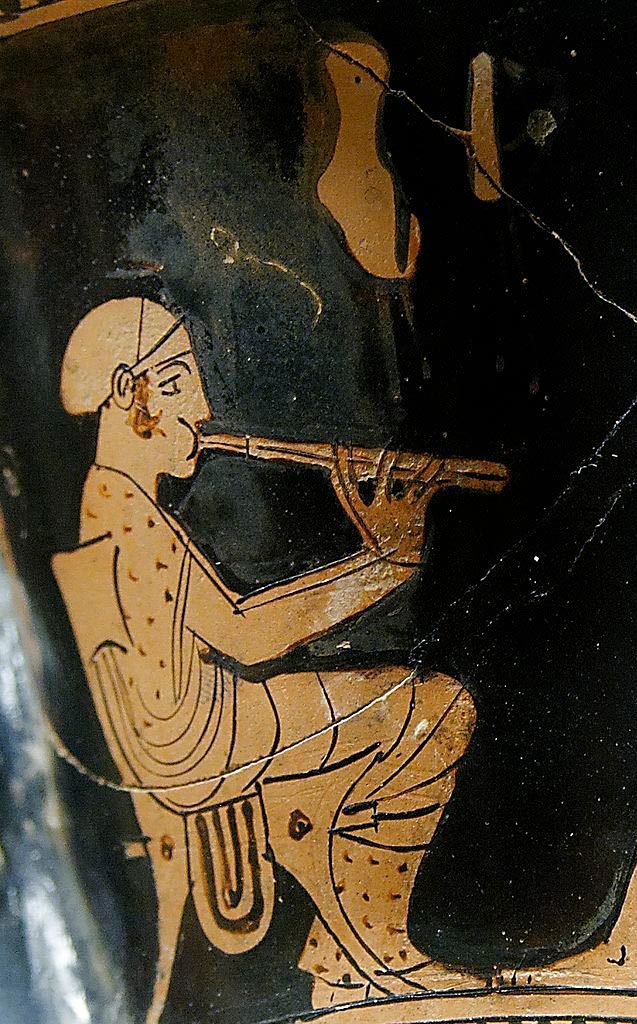

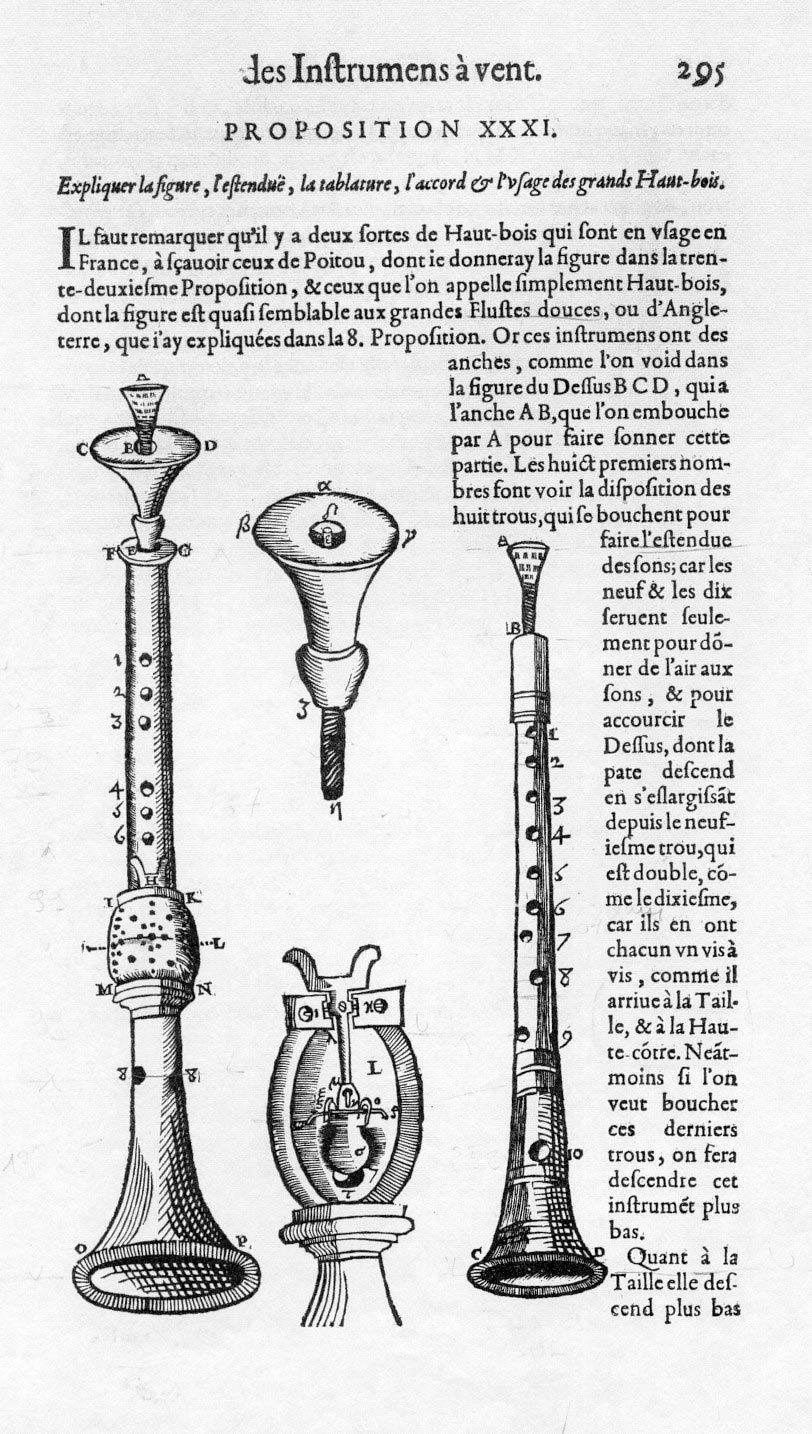

Le hautbois est un instrument de la famille des bois à perce conique et à anche double, connu dès l’Antiquité sous sa forme primitive, notamment l’aulos grec et la tibia romaine, dont l’iconographie nous donne de multiples représentations. Au Moyen-Âge et à la Renaissance, sa variante la plus répandue est la chalemie, tournée en une seule pièce et à pavillon à large perce. Apparaissant fréquemment sur les enluminures, tapisseries et sculptures, elle était jouée dans des contextes précis, pour accompagner des danses ou lors d’hymnes religieux – en atteste le célèbre exemple des Cantigas de Santa Maria (vers 1221-1284) en l’honneur de la Vierge Marie. Cet ancêtre du hautbois fut ainsi très répandu durant le Moyen-Âge et la Renaissance. L’Harmonie Universelle de 1636 de Marin Mersenne offre un beau témoignage du hautbois du XVIIème siècle, peu de temps avec que les Hotteterre et Danican Philidor le fassent évoluer en sa forme baroque autour de 1650.

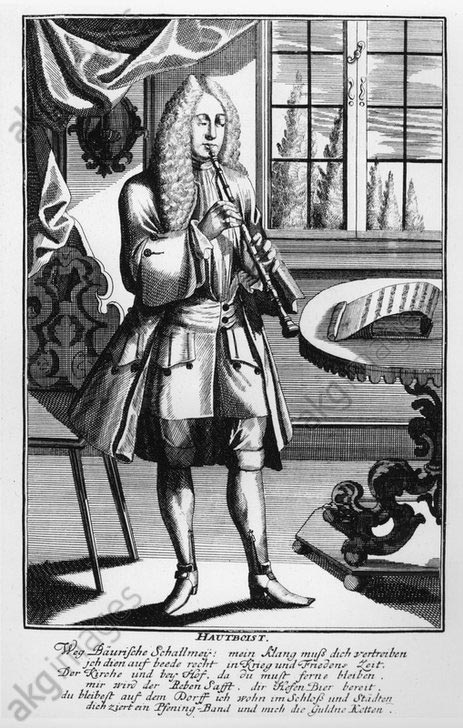

On voit alors apparaître un grand hautbois à une clé, divisé en trois parties, dont la perce est affinée, aux trous de notes ajustés et à décor de moulures. Les musiciens abandonnent aussi la pirouette, petite pièce cylindrique en bois qui entourait l’anche. L’instrument est dénommé “cromorne” à la Cour. Selon Henri Prunières, on doit à Jean-Baptiste Lully la première représentation en concert du hautbois dans le ballet de l’Amour Malade de 1657. L’instrument faisait partie de l’univers musical de la cour des rois et, de manière générale, était très répandu en Europe au XVIIème siècle.

“Sa voix haute et claire, sa tessiture importante et son indéniable souplesse d’utilisation lui confèrent un rôle de premier plan aussi bien dans les cérémonies protocolaires, militaires et festives de la haute société, que dans les réjouissances publiques des citadins et des ruraux.”

Marc Ecochard, Les hautbois dans la société française du XVIIe siècle : une approche par l’Harmonie universelle de Marin Mersenne et sa correspondance, mémoire de l’Université de Poitiers, juin 2001, p.79

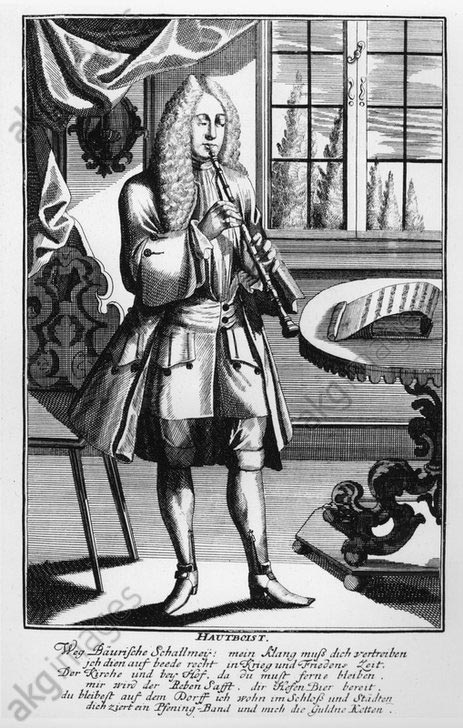

D’une clé, l’instrument passa à deux et trois clés probablement autour de 1670, comme le confirme une représentation gravée de 1672[1]. Le hautbois baroque comportait une clé pour le do grave et une pour le mi bémol. Ce nouvel instrument rencontra un grand succès en France, Angleterre, Allemagne ou encore aux Pays-Bas. À la fin du siècle, Paris était un centre important pour la facture d’instrument et on énumère en 1692 treize maîtres, dont les membres de la famille Hotteterre et Philidor. À partir des années 1720, la facture parisienne connut un nouvel essor, notamment impulsé par l’atelier de Charles Joseph Bizey (c 1695-1758), l’un des meilleurs facteurs du XVIIIème siècle. En 1716, Bizey avait obtenu son brevet de maîtrise de la communauté des facteurs et musiciens de Paris et s’était probablement installé rue Mazarine, avant de déménager dans la rue Dauphine aux alentours de 1745. Il se fit très vite un nom, puisque dès 1721, il fournit deux hautbois à la cour de Munich[2]. En effet, c’est principalement pour ses hautbois qu’il se fit connaître – ces derniers étant jugés exceptionnellement fins. Il fit ainsi des instruments à anches sa spécialité et en produisit des modèles innovants et de la plus haute qualité, marqués de son nom et d’une fleur de lys. À titre d’exemple, il mit au point un nouveau hautbois baryton de grand intérêt, qui fut redessiné par Guillaume Triebert en 1823. Comme on peut le lire dans le Mercure de France de décembre 1749 :

“le sieur Bizey, inventeur de plusieurs instruments à vent, avertit qu’il travaille toujours avec succès et perfectionne plus que jamais ces sortes d’instruments. […] il a même depuis peu inventé des Hautbois qui descendent jusqu’au Gerésol, comme le violon : il en a aussi inventé d’autres qui sont à l’octave des Hautbois ordinaires, imitant parfaitement le Cor-de-Chasse.”

Le Mercure de France, décembre 1749, dans William Waterhouse, The New Langwill, Tony Bingham, 1993, p.34

Malheureusement, peu de ses instruments nous sont parvenus. Le modèle de la vente du 7 mai 2022 en est un rare témoignage. Réalisé vers 1730, il offre un parfait exemple de l’excellent savoir-faire de Bizey et annonce la facture des modèles de la fin du siècle. En buis de bonne qualité, il est estampillé sur tous les corps d’une fleur de lys.

[1] Charles Emmanuel Borjon de Scellery, Traité de la musette, 1672, voir le frontispice

[2] Susannah Cleveland, Eighteenth-Century French Oboes: A Comparative Study. Master of Music (Musicology), Mai 2001, p.14

Bizey est le premier d’une dynastie de facteurs de grande renommée installés dans l’atelier de la rue Dauphine, puisque celui-ci fut repris par son élève Prudent avant d’être racheté par Dominique Porthaux – tous deux mariés à un membre de la famille de Bizey. Dominique Antony Porthaux est né vers 1751 et est mort à Paris le 3 février 1839. En 1777, il épousa Elizabeth Thieriot, la sœur de Prudent et reprit peu de temps après l’atelier. Ses instruments furent vite réputés et il devint en 1785 le fabricant d’instruments militaires du roi, peu avant la Révolution. En 1787, Etienne Ozi vante la qualité de ses instruments dans sa Méthode nouvelle et raisonnée pour le basson. Ses bassons préfigurent ce que l’on appellera le basson français au XIXe siècle, par opposition au basson allemand. Entre les années 1793 et 1802, Porthaux fut également éditeur et marchand de musique.

En 1808, il publia un “avis aux artistes et amateurs du basson” revendiquant l’antériorité de l’invention d’une crosse en bois, que Savary aurait imitée. Les variations de sa marque comprennent une étoile à cinq branches au-dessus de “PORTHAUX/A PARIS”, une étoile à cinq branches au-dessus de “PORTHAUX/A PARIS/R” et une couronne au-dessus de “PORTHAUX/A PARIS”[1], comme on peut le voir sur l’instrument de la vente Vichy Enchères du 7 mai 2022. Cet instrument est particulièrement rare et intéressant eu égard à la production de Porthaux, car on ne lui connaît que cinq hautbois, contre environ 22 bassons[2]. Ce hautbois est donc un exceptionnel témoignage de sa facture et de son lien avec Charles Bizey.

[1] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill, Tony Bingham, 1993, p.307

[2] Phillip T. Young, 4900 Historical Woodwind Instruments, Tony Bingham, London, 1993, p.180

L’Allemagne fut aussi un centre important pour la facture instrumentale du hautbois. Les premiers ateliers se développèrent autour de facteurs, tels que les Denner, Schell, Oberlender et Löhner à Nuremberg. La ville de Nuremberg devint le premier centre de développement des instruments à vent grâce au travail de Christoph Denner et Johann Schell dans les années 1690, puis de Jacob Denner à partir de 1707. Dresde tint une place également importante dans l’élaboration du nouveau hautbois, puisqu’elle fournit de nombreux facteurs majeurs, tels que Augustin Grenser et Jakob Grundmann, Heinrich Grenser et Floth, à qui on doit l’invention d’un modèle classique qui sera joué dans toute l’Europe jusque vers 1815[1].

La vente du 7 mai 2022 de Vichy Enchères nous donne à voir un remarquable modèle de cette époque, réalisé au début du XIXème siècle par Carl Gottlob Borman. À huit clés en laiton, il témoigne de l’adjonction progressive de clés supplémentaires et des expérimentations menées pour améliorer le son des hautbois. Carl Gottlob Borman s’inscrit dans la lignée des facteurs majeurs de la ville de Dresde précédemment cités, puisqu’il succède en 1808 à J.F. Floth, après que ce dernier ait repris l’atelier de Jakob Grundmann en 1800. À l’image de ce hautbois, les instruments de Dresde étaient très recherchés et furent adoptés dans les autres pays d’Europe. Signalons qu’un très bel hautbois en buis, à quatre bagues en ivoire et douze clés d’argent, réalisé par Johann Christopher Selboe vers 1845, figure également dans le remarquable ensemble des instruments de la vente du 7 mai 2022. Originaire de Copenhague, ce facteur se forma en parcourant l’Allemagne et vécut notamment à Dresde…

Outre Dresde et Nuremberg, la ville de Roding livra aussi de grands facteurs, dont firent partie les membres de la famille Kinigsperger, aussi orthographiée Königsberger, Koenigsperger, Kinigspergr, ou Kenigsperger. Le fondateur de la dynastie est Johann Andreas Kinigsperger (d. 1753-1757). Ce dernier s’installa en 1699 à Roding, après avoir vécu à Kirchenrohrbach. Dans le registre paroissial de la ville, il est inscrit comme facteur de flûtes et de bassons. En réalité, il semble qu’il fut tourneur en bois de formation, au même titre que le célèbre facteur de flûte Johann Heitz, dont une flûte piccolo lui étant attribuée est au catalogue de la vente le 7 mai 2022. Andreas Kinigsperger jouissait d’une certaine position sociale et semble avoir été une personnalité importante de la ville, puisqu’il fut notamment membre du conseil de Roding.

Les instruments d’Andreas Kinigsperger sont particulièrement importants pour leur valeur historique et esthétique. Le modèle de la vente du 7 mai 2022 est un hautbois ténor en bois fruitier, à trois clés en laiton et estampillé sur le pavillon de la marque du facteur “A. KINIGSPERGR” et sur les corps d’une fleur de lys. Daté de la première moitié du XVIIIème siècle, il s’agit de l’un des rares instruments de la famille Kinigsperger parvenu jusqu’à nous, et qui plus est en bon état. La dernière vente d’un de leurs instruments remonte à 2011, lorsque nous adjugions 25,000 euros une superbe taille de hautbois réalisée par Johann Wolfgang Königsberger.

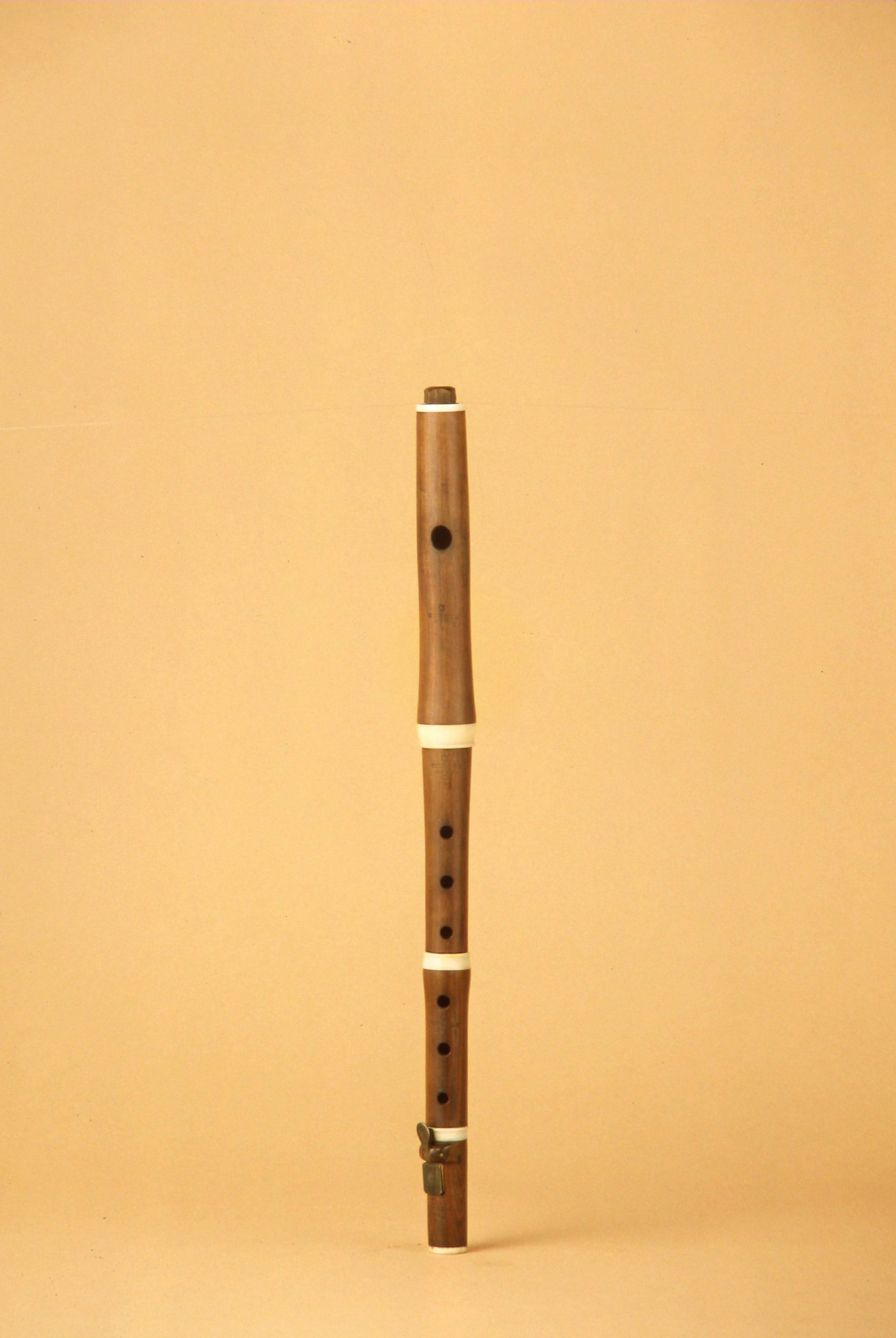

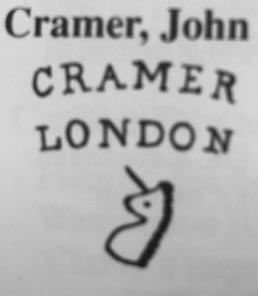

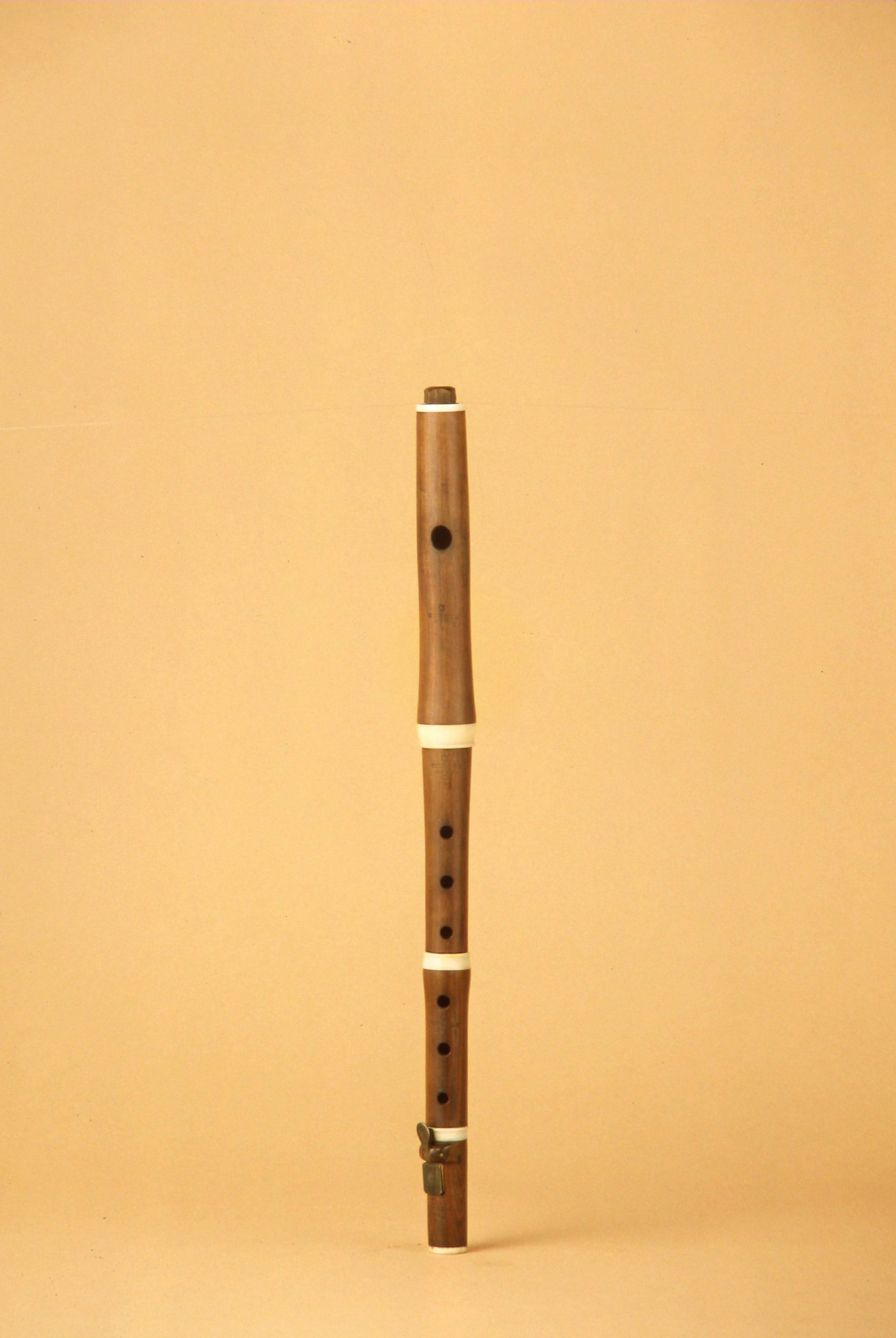

Principalement à partir du modèle français, le hautbois fut diffusé dans chaque pays avec ses propres spécificités, notamment concernant le diapason pouvant considérablement varier en fonction des pays et des époques. Pour ce qui est de l’Angleterre, le hautbois baroque se répandit dès les années 1670, en partie grâce à des compositeurs français, à l’instar de Jacques Paisible ou par le biais de facteurs dont Pierre Jaillard – dit Peter Bressan (1663-1732) – est l’exemple le plus fameux. Comme nous l’avons entrevu, c’est vers 1750 que le hautbois évolua de façon significative, sous l’influence conjuguée des changements de goûts musicaux et des demandes des musiciens et compositeurs. La perce devint plus étroite, les parois s’amincirent et les trous d’accord devinrent plus petits, donnant à l’instrument une sonorité plus claire et nuancée. À cette époque, Londres rassemblait un grand nombre d’ateliers, dont celui de Cramer. John Cramer travailla avec G. Miller de 1790 à 1796 au “3 Dacre St, Westmisnter”[1] et fut répertorié comme facteur en 1794. Entre 1796 et 1802, on le retrouve au 20 Charing Cross.

[1] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill, Tony Bingham, 1993, p.75

En 1799, il est qualifié de facteur d’instruments pour leurs Majestés (“musical inst. maker to their Majesties”) et en 1799-1803 de “Martial Mus. Inst. Mkr.”. Ses instruments sont estampillés “CRAMER/LONDON” avec le symbole d’une tête de licorne. Comme l’indique l’estampille de l’instrument de la vente du 7 mai 2022 “CRAMER London (unicorn head), Dacre strt Westr”, ce superbe hautbois en buis à deux clés a été réalisé très tôt, probablement vers 1790-1796, alors que Cramer travaillait au 3 Dacre St.

Autour de 1805-07, l’atelier de Cramer collabore avec T. Key et les instruments sont marqués “Cramer & Key”[1]. John Cramer était spécialisé dans la facture d’instruments à vent et ces derniers étaient très appréciés, à en juger par les critiques de l’époque. À titre d’exemple, le chef d’orchestre John Pearce écrivit avoir “appris de la meilleure autorité que… les clarinettes Cramer et Milhouse [W. Milhouse] sont réputées être supérieures à toutes les autres”. En outre, on peut lire dans la British Encyclopedia de 1809 que : “‘it is a great pity that very few bassoons are perfectly in tune; those made by Barker [=Parker], Wood, Millhouse [=Milhouse], and Cramer are generally preferred”.

[1] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill, Tony Bingham, 1993, p.75

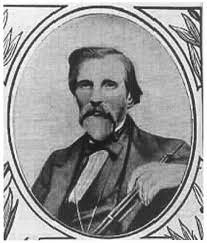

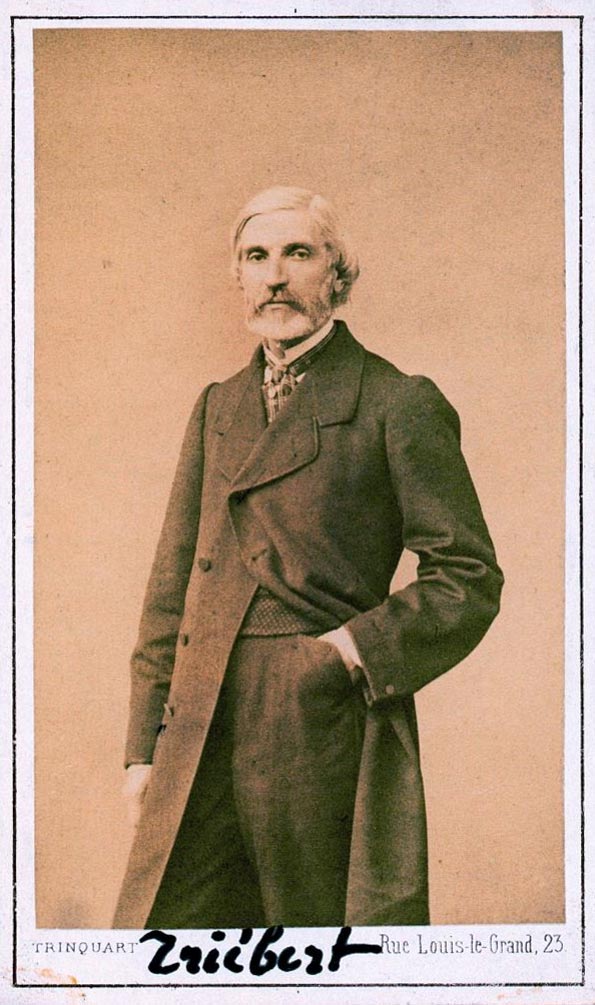

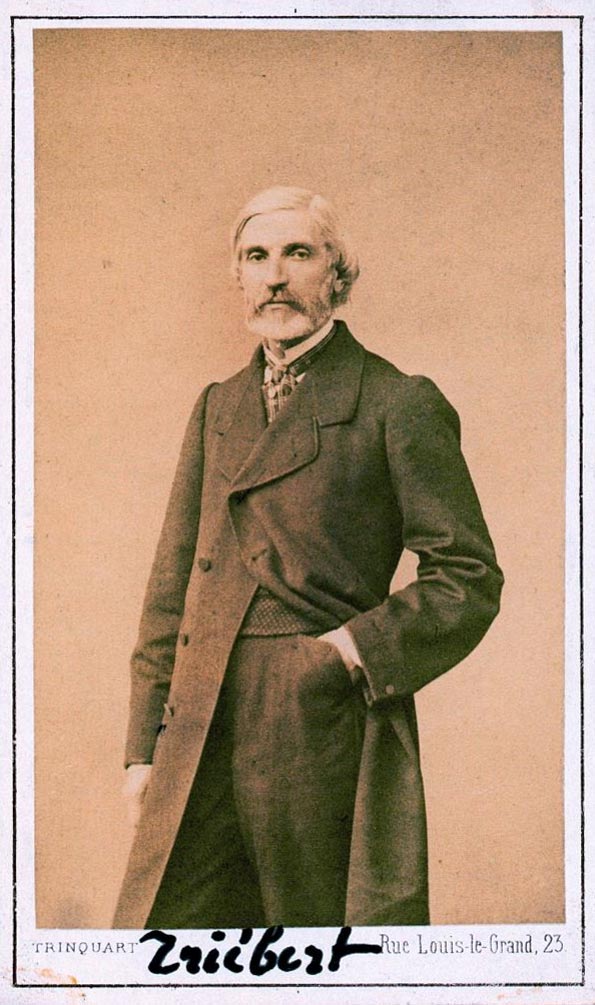

À la fin du XVIIIème siècle et durant le XIXème siècle, les Triebert jouèrent un rôle déterminant dans l’évolution et le perfectionnement du hautbois. À tel point qu’ils restent aujourd’hui considérés comme les pères du hautbois moderne. Il faut bien reconnaître qu’au XIXème siècle, Guillaume Triebert (1770-1848) et son fils Frédéric (1813-1878) – plus que nul autre – jouissent d’une renommée internationale et d’une estime leur valant de multiples récompenses et hommages.

Originaire d’Allemagne et plus précisément de Stockdorf bei Alsfeld dans la Hesse, Guillaume Triebert – de son vrai nom Georg Ludwig Wihelm – gagna Paris à pieds en 1804, après une formation d’ébéniste. Ainsi installé en France, il francisa son nom et se fit appeler Guillaume. Il ne s’établit à son compte qu’en 1810, après avoir travaillé en tant qu’ébéniste et pour le facteur d’instruments à vent Nicolas Viennen. Il rencontra très vite le succès et travailla pour les musiciens les plus en vue de l’époque, à l’instar de l’hautboïste Gustave Vogt, pour qui il redessina en 1823 le célèbre baryton inventé par Charles Bizey (cf plus haut). Ce baryton, percé de 11 trous dont 8 bouchés par des clés, remporta une médaille de bronze à l’exposition de 1827. Au même moment, Triebert réalisa un très bel hautbois à huit clés en laiton qui sera vendu le 7 mai 2022 à Vichy Enchères. Estampillé “Triebert à Paris” au-dessus de la tour à trois merlons, celui-ci nous offre un remarquable témoignage du savoir-faire de Guillaume Triebert à cette époque.

Son succès ne s’arrêta pas là, puisque ses instruments furent jugés “exceptionnels” aux différentes expositions internationales. Ainsi, à l’Exposition de Paris de 1834, ses hautbois furent qualifiés de supérieurs à tous les autres.

Ce succès s’explique par toutes les innovations qu’il mit en œuvre pour perfectionner le hautbois.

Il expose deux cors anglais (hautbois alto), instrument peu connu, il y a quelques années, et notablement perfectionné par M. Triebert. On remarquera aussi quatre hautbois de divers genres et de systèmes différens [sic], dont l’un est fabriqué d’après une nouvelle méthode, et les clés sont placées de manière à rendre l’exécution plus complète et plus sûre. Ces instruments ont été fournis à l’école de musique par M. Triebert.

Notice des produits de l’industrie française, précédée d’un historique des expositions antérieures et d’un coup d’oeil général sur l’Exposition actuelle, 1834, p.165

C’est ainsi le premier à introduire la mécanisation du hautbois à partir d’un mécanisme inspiré du système Boehm, composé “d’un nombre variable de clefs et de la lunette de fa#” qu’il nomme « système 3 »” . Le deuxième instrument de la vente du 7 mai 2022 de Guillaume Triebert s’inscrit pleinement dans cette période, puisqu’il a été réalisé vers 1835. En bon état, ce hautbois de grande qualité est en buis teinté et présente quatre bagues d’ivoire et onze clés en laiton. Il est estampillé “Triebert à Paris” au-dessus de la marque de la famille : la tour à trois ou quatre merlons.

C’est grâce à l’application au hautbois de la perce de Boehm, perfectionnée par M. Triébert, que cet instrument n’est pas resté en arrière des progrès de toute la facture.

Oscar Comettant, La musique, les musiciens et les instruments de musique, Archives complètes de tous les documents qui se rattachent à l’Exposition internationale de 1867, Michel Lévy Frères, 1869 p.713

Guillaume Triebert eut plusieurs enfants, dont le célèbre hautboïste, compositeur et professeur au Conservatoire de Paris : Charles-Louis Triebert (1810-1867). Il est peu probable que ce dernier ait joué un rôle important dans l’atelier, à la différence de son frère Frédéric. Musicien également – il fut second hautbois à l’Opéra-Comique -, Frédéric remplaça Guillaume Triebert à son départ à la retraite en 1845. Avec lui, les instruments Triebert atteignirent le plus haut degré de perfectionnement et la plus haute reconnaissance. Reprenant l’invention du “système 3” de son père, il en améliora toutefois la conception, comme en témoigne le hautbois en grenadille “système 3”, réalisé vers 1850, de la vente Vichy Enchères du 7 mai 2022.

Ses améliorations du “système 3” l’amenèrent à créer le “système 4” en 1843, qui fut notamment utilisé par son frère Charles au Conservatoire de Paris. Toute sa vie, il travailla sur de nouveaux systèmes de clétage pour perfectionner le hautbois, en collaboration avec des musiciens, tels que Apollon Marie-Rose Barret (système 5, 1849), Georges Gillet (système 6, 1875) ou Eugène Jancourt. Fort de toutes ses innovations, il acquit une renommée internationale et exporta de nombreux instruments, notamment en Angleterre, où le système “thumbplate” (système 5) est encore utilisé aujourd’hui.[1] Les grands musiciens de son temps jouèrent ainsi sur des instruments Triebert, à l’instar d’Albert Delabarre (1809-1885) au Théâtre de la Monnaie de Bruxelles. Après avoir remporté des médailles à l’exposition de Paris de 1827, 1839, 1844, la Maison Triebert continua d’être célébrée sous la direction de Frédéric en 1849, 1851 (Londres), 1855, 1862 (Londres) et 1867.[2]

[1] Robert Howe, “On the Dating of Instruments Marked “Triebert””, Journal of the American Musical Instrument Society, 2019, p.1

[2] Robert Howe, “On the Dating of Instruments Marked “Triebert””, Journal of the American Musical Instrument Society, 2019, p.3

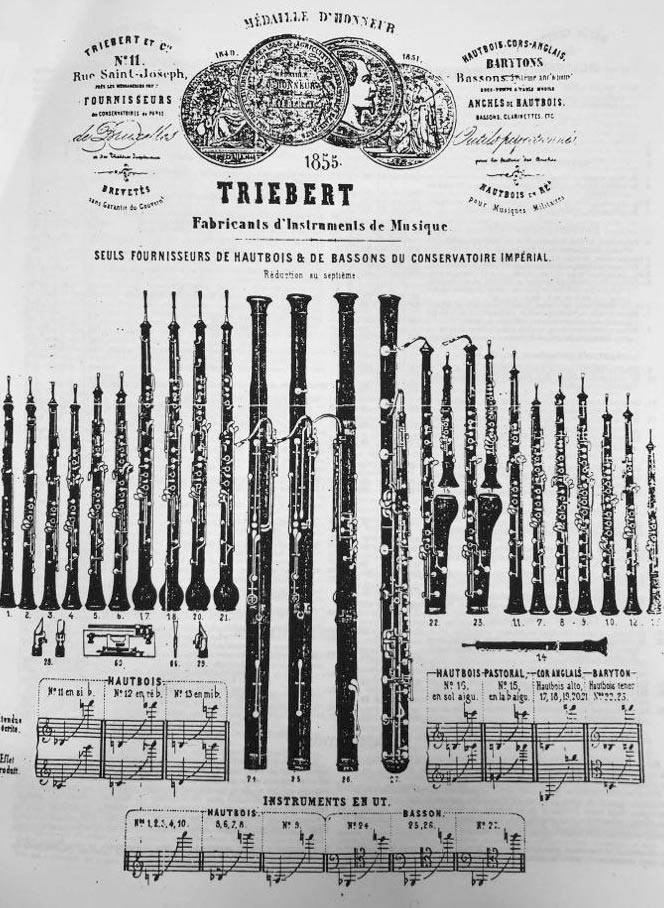

La vente du 7 mai 2022 présente un magnifique instrument de Frédéric Triebert peu courant : un hautbois baryton. Ce modèle en grenadille est composé de treize clés en maillechort et estampillé sur tous les corps de la tour à quatre merlons. À la différence des tours à trois merlons présentes sur les autres instruments de la vente, celle-ci est utilisée dès 1825 pour les barytons, cors anglais courbes et les bassons. Cependant, comme le souligne Robert Howe dans son étude sur la datation des instruments de la Maison Triebert, le mécanisme et la marque indiquent qu’il date au moins de 1845[1], puisqu’il est marqué “BREVETE”. Cette marque était rendue obligatoire depuis une loi de 1844. Par ailleurs, la mention “F. Paris Succr” n’apparaît pas, ce qui signifie que l’instrument est antérieur à 1870. Autre élément très intéressant, en 1855, le catalogue d’instruments Triebert mettait à l’honneur, en couverture, deux barytons dont un modèle similaire (n°22) à celui de la vente Vichy Enchères. À son propos, Triebert soulignait que sa “qualité de son est belle et [qu’il] ne manque pas de puissance.” Il ajoutait que selon lui, la baryton avait un rôle important à jouer.

[1] Nous remercions Robert Howe pour ces observations

Cette remarque, conjuguée au fait que l’instrument soit en couverture, indique que le baryton était cher à Frédéric Triebert. Son travail sur l’instrument fut d’ailleurs salué par la critique, puisque le rapport du jury de l’Exposition universelle de la même année 1855 affirma :

“On doit aussi, aux mêmes facteurs, la résurrection du ténor de hautbois, auquel ils ont donné le nom de baryton, et qu’ils ont construit dans des conditions analogues à celles du hautbois et du cor anglais. La sonorité de l’instrument est très-satisfaisante et bien identique à celle du soprano et du contralto de la même famille”.

Exposition universelle de 1855 : Rapports du jury mixte international, Volume 2, 1856, p.661

En outre, lors de l’Exposition universelle de 1862, l’instrument fut très apprécié et qualifié de “fort remarquable et fort remarqué par la pureté de ses intonations.”[2] Le modèle en vente le 7 mai 2022 est donc particulièrement intéressant et reste rare, malgré l’importance que Frédéric Triebert lui accordé et les éloges dont il fut l’objet au milieu du XIXème siècle.

[2] Adolphe Le Doulcet marquis de Pontécoulant, Douze jours à Londres, voyage d’un mélomane à travers l’Exposition universelle, F. Henry, 1862, p.233

Rendez-vous lors des journées d’exposition pour contempler ces merveilles de l’histoire de la facture instrumentale du hautbois, et le samedi 7 mai 2022 pour leur vente !

Our sale of wind and plucked string instruments on 7 May 2022 will bring together an exceptional set of oboes that spans the history of the instrument in the 18th century, until its peak in the time of Guillaume and Frederic Triebert. Through instruments by important makers such as Charles Bizey, Dominique Porthaux, the Bormans, Kinigsperger, Cramer, and of course Trieberts, part of the history of European oboe making will reveal itself before your eyes. This set of instruments will also provide an opportunity to discover a superb baritone oboe by Frédéric Triebert, based on a model that appeared in the instruments catalogue of the House in 1855.

The oboe is an instrument of the woodwind family, with a conical bore and a double reed, known since the Antiquity in its primitive form, in particular the Greek aulos and the Roman tibia, and which is often represented in the art of these civilizations. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, its most widespread form was the shawm, turned in one piece and with a large bore bell. Frequently appearing on manuscripts, tapestries and sculptures, it was played on particular occasions, often to accompany dances or religious hymns – as in the famous case of the Cantigas de Santa Maria (aroub 1221-1284) in honour of the Virgin Mary. This predecessor to the oboe was therefore very widespread during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. The Harmonie Universelle of 1636 by Marin Mersenne provides a comprehensive overview of the oboe in the 17th century, shortly before the Hotteterres and Danican Philidor made it evolve into its baroque form around 1650.

We then see a large one-key oboe appear, divided into three parts, with a refined bore, modified note holes and decorated with mouldings. Musicians also abandoned the “pirouette”, a small cylindrical piece of wood that surrounded the reed. The instrument was called “cromorne” at Court. According to Henri Prunières, we owe Jean-Baptiste Lully the first concert performance of the oboe in the ballet of the Amour Malade of 1657. The instrument made regular appearances in Court music and, more generally, was widespread in Europe in the 17th century.

“Its high and clear voice, its wide range and its undeniable versatility explain why it took a leading role in formal, military and festive ceremonies in high society, as well as in public celebrations in towns and villages.”

Marc Ecochard, Les hautbois dans la société française du XVIIe siècle : une approche par l’Harmonie universelle de Marin Mersenne et sa correspondance, mémoire de l’Université de Poitiers, juin 2001, p.79

From one key, the instrument transitioned to two and three keys, probably around 1670, as confirmed by an engraving of 1672[1]. The baroque oboe had a key for the low C and one for the E flat. This new instrument was very popular in France, England, Germany and the Netherlands. At the end of the century, Paris was an important centre for instrument making and in 1692 thirteen master makers were listed there, including members of the Hotteterre and Philidor families. From the 1720s, Parisian making experienced a new boom, driven in particular by the workshop of Charles Joseph Bizey (c 1695-1758), one of the best makers of the 18th century. In 1716, Bizey obtained his master’s degree from the community of makers and musicians of Paris and probably settled on rue Mazarine, before moving to a nearby street, rue Dauphine, around 1745. He quickly made a name for himself, and, in 1721, supplied two oboes to the court of Munich[2]. He became known mainly for his oboes, which were considered exceptionally fine. As a result, he focused his production on reed instruments and created innovative models of the highest quality, branded with his name and a fleur-de-lys. For instance, he developed a new baritone oboe of great merit, which was modified by Guillaume Triebert in 1823. As published in the Mercure de France of December 1749:

“Sir Bizey, inventor of several wind instruments, states that he always achieves results in his work and endeavours to bring perfection to these kinds of instruments more than ever before. […] he even recently invented oboes that go down to the G below middle C, like the violin: he also invented others which are an octave below ordinary oboes, perfectly imitating the hunting horn.”

Le Mercure de France, décembre 1749, dans William Waterhouse, The New Langwill, Tony Bingham, 1993, p.34

Unfortunately, few of his instruments have survived. The instrument by him in the sale of 7 May 2022 is a rare example. Made around 1730, it offers a perfect example of Bizey’s excellent craftsmanship and heralds the making of the models of the end of the century. It is made from good quality boxwood, and is stamped on all its parts with a fleur-de-lys.

[1] Charles Emmanuel Borjon de Scellery, Traité de la musette, 1672, voir le frontispice

[2] Susannah Cleveland, Eighteenth-Century French Oboes: A Comparative Study. Master of Music (Musicology), Mai 2001, p.14

Bizey is the first of a dynasty of renowned makers established in the workshop on rue Dauphine, which was first taken over by his pupil Prudent before being bought by Dominique Porthaux – both of whom married a member of the Bizey family. Dominique Antony Porthaux was born around 1751 and died in Paris on 3 February 1839. In 1777, he married Elizabeth Thieriot, Prudent’s sister, and shortly afterwards took over the workshop. His instruments were quickly in demand and in 1785, shortly before the Revolution, he became the king’s manufacturer of military musical instruments. In 1787, Etienne Ozi praised the quality of his instruments in his Methode nouvelle et raisonnee pour le basson. His bassoons herald what will be called the French bassoon in the 19th century, in opposition to the German bassoon. Between 1793 and 1802, Porthaux was also a music publisher and seller.d de musique.

In 1808, he published a “notice to artists and lovers of the bassoon” claiming the invention of a wooden cross, which Savary would have imitated. Variations of its brand include a five-pointed star above “PORTHAUX/A PARIS”, a five-pointed star above “PORTHAUX/A PARIS/R” and a crown above “PORTHAUX/A PARIS”[1], as featured on the instrument in the Vichy Enchères sale of 7 May 2022. This instrument is particularly rare and interesting in light of Porthaux’s output, since only five oboes are known to have been made by him, versus about 22 bassoons[2]. This oboe is therefore an exceptional testimony to his craftsmanship and his connection with Charles Bizey.

[1] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill, Tony Bingham, 1993, p.307

[2] Phillip T. Young, 4900 Historical Woodwind Instruments, Tony Bingham, London, 1993, p.180

Germany was also an important centre for oboe making. The first workshops were established in Nuremberg by family of makers such as the Denners, Schells, Oberlenders and Löhners. The city of Nuremberg became the foremost centre for wind instrument making thanks to the work of Christoph Denner and Johann Schell in the 1690s, and then of Jacob Denner from 1707. Dresden held an equally important place in the development of the new oboe, since many important makers were established there, as for instance Augustin Grenser, Jakob Grundmann, Heinrich Grenser and Floth, to whom we owe the invention of a classical model which was played throughout Europe until around 1815[1].

The Vichy Enchères sale on 7 May 2022 includes a remarkable example from this period, made at the beginning of the 19th century by Carl Gottlob Borman. Its eight brass keys bear witness to the gradual inclusion of additional keys and to the experiments carried out to improve the sound of oboes. Carl Gottlob Borman is part of the important Dresden makers mentioned above, since he succeeded J.F. Floth in 1808, after the latter had taken over Jakob Grundmann’s workshop in 1800. Oboes made in Dresden such as these were much sought after and were widespread in other European countries. It’s worth mentioning that a very beautiful boxwood oboe, with four ivory rings and twelve silver keys, made by Johann Christopher Selboe around 1845, is also part of the remarkable set of instruments on sale on 7 May 2022. Originally from Copenhagen, this maker trained during his travels through Germany and in particular in Dresden where he lived.

In addition to Dresden and Nuremberg, the city of Roding also produced important makers, including the members of the Kinigsperger family, whose name is also spelled Königsberger, Koenigsperger, Kinigspergr and Kenigsperger. The founder of the dynasty is Johann Andreas Kinigsperger (d. 1753-1757). He settled in Roding in 1699, having previously lived in Kirchenrohrbach. In the parish register of the city, he is listed as a flute and bassoon maker. In reality, it appears he trained as a woodturner, like the famous flute maker Johann Heitz; a piccolo flute attributed to him is also included in sale of 7 May 2022. Andreas Kinigsperger attained a certain social status and seems to have been an important figure of the city, since he was a member of the council of Roding.

Andreas Kinigsperger’s instruments are particularly important for their historical and aesthetic value. The example in the 7 May 2022 sale is a tenor oboe in fruitwood, with three brass keys, and is stamped on the pavilion with the maker’s brand “A. KINIGSPERGR” and on the body parts with a fleur-de-lis. Dating from the first half of the 18th century, it is one of the rare instruments of the Kinigsperger family to have survived to this day, and to have done so in good condition. The last sale of one of their instruments dates back to 2011, when a large size oboe made by Johann Wolfgang Königsberger sold for 25,000 euros.

While it mainly followed the French model, the oboe developed in each country with its own regional variations, in particular regarding its pitch, which could vary considerably depending on the country and the time. In England, the baroque oboe spread from the 1670s, in part thanks to French composers like Jacques Paisible, but also instrument makers, of which Pierre Jaillard – known as Peter Bressan (1663-1732) – was the most famous. As discussed previously, it was around 1750 that the oboe evolved significantly, under the combined influence of changes in musical tastes and the demands of musicians and composers. The bore became narrower, the walls thinner, and the note holes became smaller, giving the instrument a clearer and more nuanced sound. At that time, London counted a large number of workshops, including that of Cramer. John Cramer worked with G. Miller from 1790 to 1796 at “3 Dacre St, Westmisnter”[1] and was registered as an instrument maker in 1794. Between 1796 and 1802 he could be found at 20 Charing Cross.

[1] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill, Tony Bingham, 1993, p.75

In 1799, he was granted the title of “musical inst. maker to their Majesties” and in 1799-1803 that of “Martial Mus. Inst. Mkr.”. His instruments are stamped “CRAMER/LONDON” with the addition of a unicorn head symbol. As indicated by the stamp on the instrument on sale on 7 May 2022 which reads “CRAMER London (unicorn head), Dacre strt Westr”, this superb boxwood oboe with two keys was made very early, probably around 1790-1796, while Cramer was still working at 3 Dacre St.

Around 1805-1807, Cramer’s workshop collaborated with T. Key and the corresponding instruments were branded “Cramer & Key”[1]. John Cramer specialized in making wind instruments and they were highly regarded, judging by the comments from the critics of the time. For example, conductor John Pearce wrote that he “gathered from the best authority that (…) the Cramer and Milhouse clarinets [W. Milhouse] are deemed to be superior to all others”?. In addition, the British Encyclopedia of 1809 reads: “‘it is a great pity that very few bassoons are perfectly in tune; those made by Barker [=Parker], Wood, Millhouse [=Milhouse], and Cramer are generally preferred”.

[1] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill, Tony Bingham, 1993, p.75

At the end of the 18th century and during the 19th century, the Trieberts played a decisive role in the development and improvement of the oboe, so much so that they are still considered today as the inventors of the modern oboe. Indeed, in the 19th century, Guillaume Triebert (1770-1848) and his son Frédéric (1813-1878) enjoyed international fame and esteem which earned them multiple awards and tributes.

Originally from Germany, and more specifically from Stockdorf bei Alsfeld in Hesse, Guillaume Triebert – whose real name is Georg Ludwig Wilhelm – reached Paris on foot in 1804, after training as a cabinetmaker. After settling in France, he changed his name to a French sounding one. He set up on his own in 1810, after working as a cabinetmaker and for the wind instrument maker Nicolas Viennen. He quickly found success and worked for the most prominent musicians of the time, such as the oboist Gustave Vogt, for whom he redesigned in 1823 the famous baritone oboe created by Charles Bizey (see above). This baritone oboe, featuring 11 holes, eight of which are operated by keys, won a bronze medal at the 1827 exhibition. Around the same time, Triebert made a very beautiful oboe with eight brass keys which will be auctioned by Vichy Encheres on 7 May 2022. It is stamped “Triebert a Paris” above the barbican-tower with three merlons, and provides us with a remarkable example of the craftsmanship of Guillaume Triebert at that time.

His success did not stop there, and his instruments were judged to be “exceptional” at various international exhibitions. For instance, at the Paris Exhibition of 1834, his oboes were judged to be superior to all others.

This success can be explained by all the innovations he implemented to improve the oboe.

He exhibits two cors anglais (alto oboe), an instrument little known a few years ago, and perfected in particular by Mr. Triebert. Please note also four oboes of various types and with different systems, one of which is made according to a new system, in which the keys are placed in such a way as to make playing more complete and assured. These instruments were supplied to the music school by Mr. Triebert.

Notice des produits de l’industrie française, précédée d’un historique des expositions antérieures et d’un coup d’oeil général sur l’Exposition actuelle, 1834, p.165

He was therefore the first to mechanize the oboe with a system inspired by that of Boehm, featuring “a variable number of keys and an F# bezel”, which he called “system 3”. The second instrument in the sale of 7 May 2022 by Guillaume Triebert is typical of this period, having been made around 1835. This high quality oboe in good condition is made of tinted boxwood and has four ivory rings and 11 brass keys. It is stamped “Triebert a Paris” above the family trademark: the barbican-tower with three or four merlons.

“Thanks to the implementation of Boehm’s bore, perfected by M. Triébert, onto this oboe, it has not become obsolete in the face of the progress made in the manufacturing of the instrument since then.“

Guillaume Triebert had several children, including Charles-Louis Triebert (1810-1867), the famous oboist, composer and professor at the Paris Conservatoire. It is unlikely that the latter played an important role in the workshop, unlike his brother Frédéric. A musician too – he was second oboe at the Opéra-Comique – it was he who replaced Guillaume Triebert when he retired in 1845. Under him, Triebert instruments reached the peak of perfection and received the highest accolades. He revisited the invention of his father, the “system 3”, and improved its design, as evidenced by the “system 3” oboe in grenadilla made around 1850, which is in the Vichy Enchères sale of 7 May 2022.

His improvements to the “system 3” led him to create a “system 4” in 1843, which was used in particular by his brother Charles at the Paris Conservatoire. All his life, he worked on new key systems to improve the oboe, in collaboration with musicians, such as Apollon Marie-Rose Barret (“system 5”, 1849), Georges Gillet (“system 6”, 1875) and Eugène Jancourt. Thanks to all his innovations, he acquired an international reputation and exported many instruments, in particular to England, where the thumbplate system (“system 5”) is still in use today.[1] The great musicians of his time therefore played on his instruments, like Albert Delabarre (1809-1885) at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels. After winning his first medal at the Paris Exhibition of 1827, others followed in 1839, 1844, 1849, 1851 (London), 1855, 1862 (London) and 1867.[2]

[1] Robert Howe, “On the Dating of Instruments Marked “Triebert””, Journal of the American Musical Instrument Society, 2019, p.1

[2] Robert Howe, “On the Dating of Instruments Marked “Triebert””, Journal of the American Musical Instrument Society, 2019, p.3

The sale of 7 May 2022 includes a magnificent and unusual instrument by Frédéric Triebert: a baritone oboe. This grenadilla example features 13 nickel silver keys and is stamped on all the body parts of the barbican-tower with four merlons. Unlike the towers with three merlons of the other instruments in the sale, this type was used from 1825 for baritones, curved cors anglais and bassoons. However, as Robert Howe points out in his study on the dating of Maison Triebert instruments, the mechanism and the brand indicate that it dates from at least 1845[1], ], since it is branded “BREVETE” (patented). This mention was compulsory by law in 1844. In addition, the mention “F. Paris Succr” does not appear, which means that the instrument is prior to 1870. Another very interesting element is the fact that the 1855 catalogue of Triebert instruments featured on its cover two baritones, including an example (n°22) similar to the one in the Vichy Enchères sale. In reference to it, Triebert pointed out that its “sound quality is beautiful and [it] does not lack power.” He added that, in his opinion, the baritone oboe had an important role to play.

[1] Nous remercions Robert Howe pour ces observations

This mention, combined with the fact that the instrument is on the cover, indicates that the baritone was dear to Frédéric Triebert. His work on the instrument was also praised by critics, as the report of the jury of the Universal Exhibition of that same year, 1855, attests:

“We also owe, to the same makers, the revival of the tenor oboe, which they named baritone, and which they constructed in similar conditions to those of the oboe and the cor anglais. The sound of the instrument is very satisfying and very similar to that of the soprano and contralto instruments of the same family“.

Exposition universelle de 1855 : Rapports du jury mixte international, Volume 2, 1856, p.661

In addition, during the Universal Exhibition of 1862, the instrument was highly praised and described as “very remarkable and distinctive for the purity of its intonation.”[2] The example on sale on 7 May 2022 is therefore particularly interesting and rare, despite being very important to Frédéric Triebert and highly praised in the middle of the 19th century.

[2] Adolphe Le Doulcet marquis de Pontécoulant, Douze jours à Londres, voyage d’un mélomane à travers l’Exposition universelle, F. Henry, 1862, p.233

We invite you to join us on the viewing days to admire these wonders of the history of oboe making, and on Saturday 7 May 2022 for their sale.