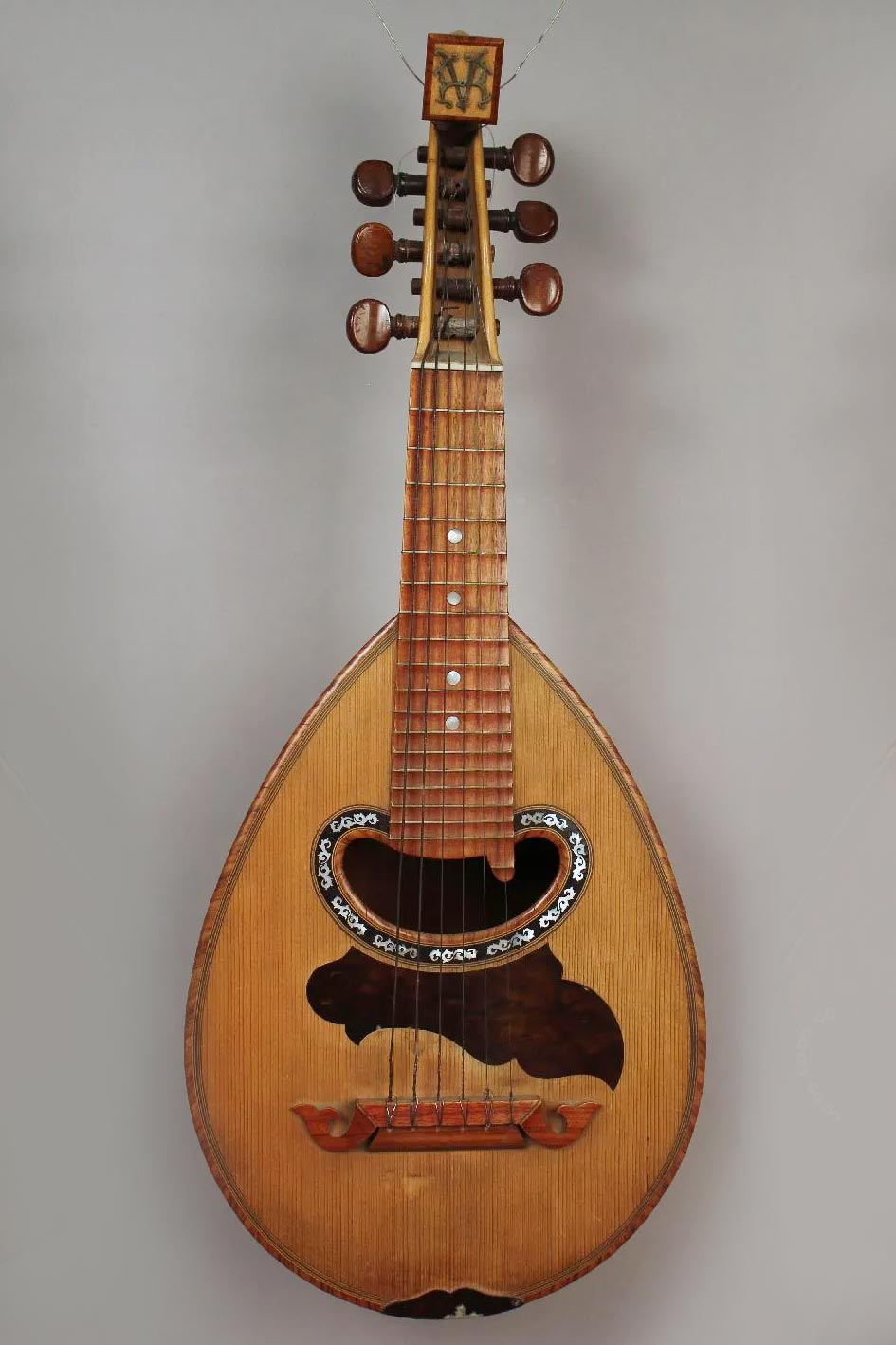

Vichy Enchères vous donne rendez-vous le 5 novembre 2022 pour la vente de cette exceptionnelle mandoline d’Antonio Vinaccia. Daté 1771, il s’agit de l’unique modèle connu présentant la marque du luthier. Également rarissime par son décor et raffinement, ce modèle évoque les plus belles heures de l’instrument à la cour des Bourbon-Siciles.

S’il est une famille qui a marqué l’histoire de la mandoline, c’est bien celle des Vinaccia. Cette dynastie de luthiers œuvra durant deux siècles au développement et à la renommée de l’instrument. Grâce à leur travail, le regard porté sur celui-ci changea et virtuoses et grands commanditaires commencèrent réellement à s’y intéresser durant le dernier tiers du XVIIIème siècle. L’histoire de la mandoline est à rattacher à celle du luth, très en vogue en Occident médiéval mais dont l’origine est orientale. Les Arabes découvrent le luth persan au VIème siècle et l’instrument est introduit en Europe via l’Espagne mauresque. Au cours du XVIIème siècle, déjà plusieurs instruments de la famille des luths préfigurant la mandoline et déclinés en différentes tailles étaient en usage. Ces premières mandolines, dîtes baroques ou mandolino, furent essentiellement conçues à Milan et se distinguent du luth par leur taille plus petite, leur caisse davantage bombée, leur manche plus court muni de frettes, mais aussi par leur tête qui n’est plus “cassée” vers l’arrière comme celle du luth.

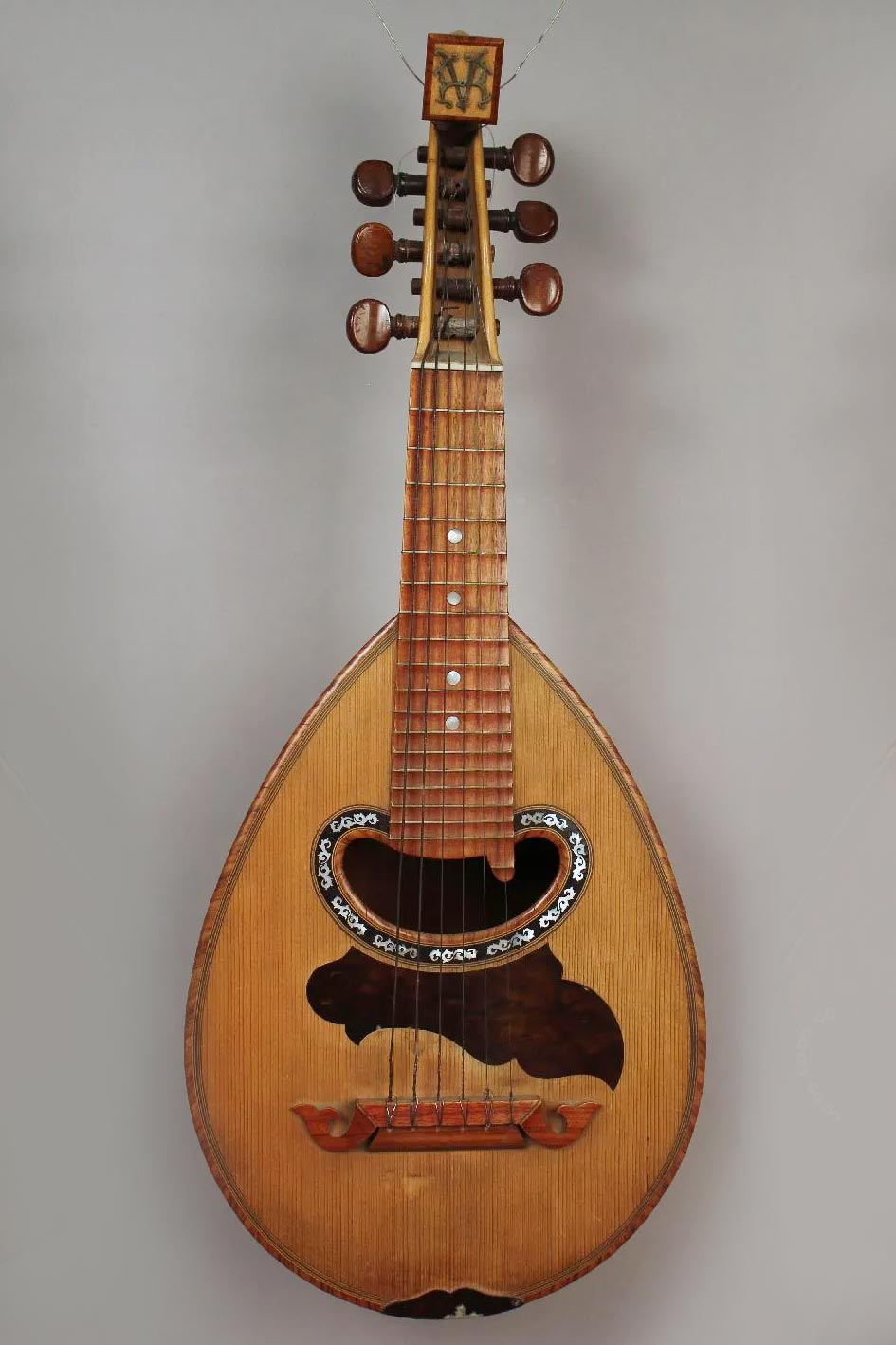

Leur corps est en forme d’amande et l’instrument présente un chevillier caractéristique en forme de “virgule”. La mandoline milanaise compte généralement six chœurs en boyau, joués avec les doigts et accordés en quartes et une tierce. C’est seulement durant la seconde moitié du XVIIIème siècle, et ce principalement à Naples, que l’instrument baroque évolue. Par opposition à la mandoline milanaise, ces nouveaux modèles sont dès lors qualifiés de mandolines napolitaines. Dans la culture commune, il est couramment admis que ce type d’instrument a été développé par la famille Vinaccia, et tout particulièrement par Gennaro et Antonio. Parmi les modèles napolitains les plus anciens parvenus jusqu’à nous, on trouve ainsi un instrument de 1759 étiqueté « Antonius Vinaccia filius January », conservé au musée de l’Université d’Edinburgh, au style plutôt sévère et dépouillé.

Dans son article sur la famille Vinaccia paru en 2017 dans le numéro 87 du magazine GuitArt, Raffaele Carpino fait le point sur les différents membres de la famille[1]. On s’accorde généralement sur le fait que la dynastie de luthiers remonte à Gennaro [I] Vinaccia (c.1710 – c.1781), actif à partir de 1734, probable disciple de l’atelier de Gagliano. Sa production comprenait guitares, violons et mandolines et il en fut de même pour ses fils. Gennero eut en effet trois fils luthiers : Antonio (actif vers 1753-1785), Giovanni (actif vers 1750-1780) et Vincenzo (actif vers 1752-1795).

[1] Raffaele Carpino, “La famiglia Vinaccia. Storia e approfondimenti dalle origini al XIX sec.”, GuitArt, n°87, 2017

Antonio Vinaccia est considéré comme le luthier le plus brillant et accompli de la dynastie. Déjà de son vivant, ses mandolines étaient très recherchées par les plus prestigieux commanditaires. Tout comme son père, il eut à son tour trois fils luthiers : Nicolas (actif vers 1770-1808), Mariano (actif vers 1775-1810) et Gaetano [I] (actif vers 1779-1848), dont la production se concentra essentiellement sur les guitares. Sans être exhaustif, citons enfin Pasquale, le fils de Gaetano, actif environ de 1828 à 1883 et dont l’œuvre eut une grande influence dans l’histoire de la mandoline moderne.

“The Vinaccia family have undoubtedly been the greatest artists in the construction of mandolines. […] Their workmanship and designs place them considerably beyond the reach of their opponents. The tone and finish of their mandolines are irreproachable. A real Vinaccia fratelli is the “Strad” of mandolines”

Richard Harrison, “The mandoline”, in The Bazaar, The Exchange and Mart, 3 janv. 1894, pp.24-25.

Les Vinaccia furent de grands innovateurs et tinrent un rôle déterminant dans l’histoire de la mandoline. Gennaro et Antonio furent parmi les premiers à revoir les proportions de l’instrument baroque. Il a été observé que les mandolines d’Antonio Vinaccia – que beaucoup considèrent comme les plus abouties – sont légèrement plus grandes que celles de Gennaro. De manière générale, ce nouveau modèle de mandoline se distingue par sa table élargie et son chevalet rehaussé (il était jusque-là positionné très bas). Entre le chevalet et la bouche, on trouve désormais une plaque d’écailles ou de bois, de manière à éviter à ce que l’instrument ne subisse des dommages. En effet, celui-ci est à présent joué à l’aide d’un plectre car ses cordes en boyau ont été remplacées par des métalliques, accordées en quintes comme le violon – facilitant son jeu pour un grand nombre de musiciens. La caisse est construite à partir de bois courbé appelé “côte”, et la table d’harmonie – auparavant plate – s’incline à partir du chevalet, au niveau de sa largeur maximale. La tête si caractéristique de la mandoline milanaise est devenue trapézoïdale, à la manière de celles des guitares. Enfin, des frettes supplémentaires ont été ajoutées pour étendre la gamme de l’instrument.

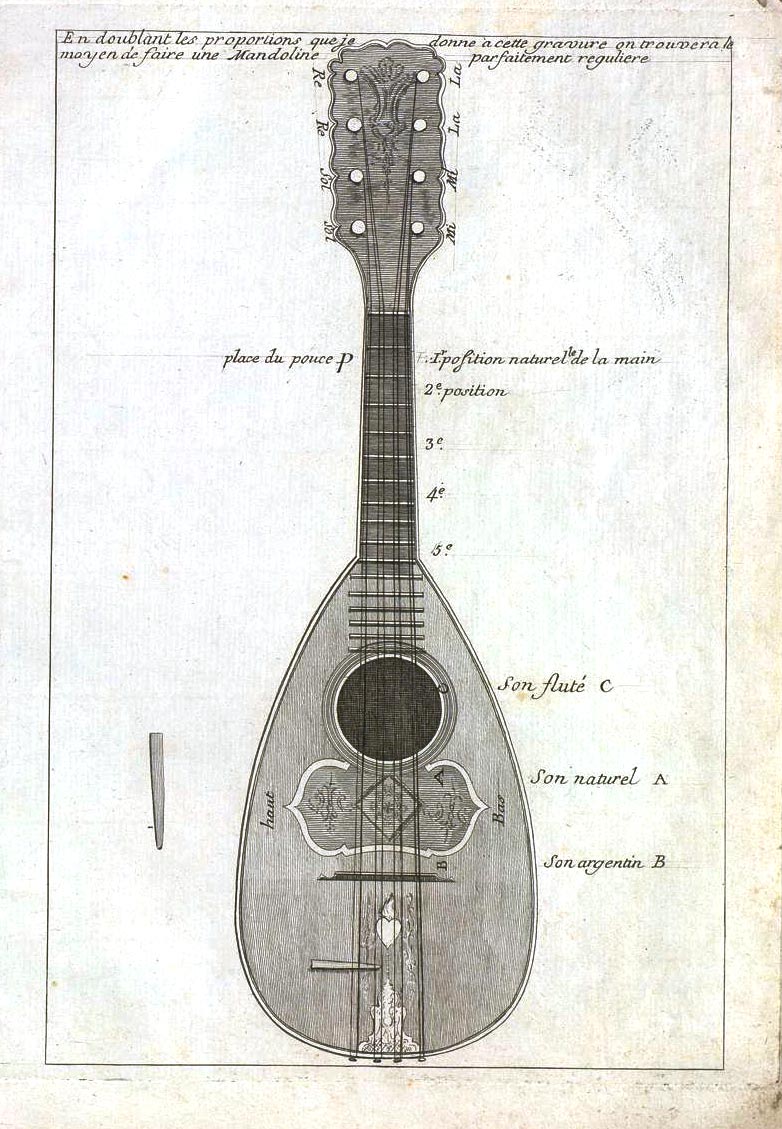

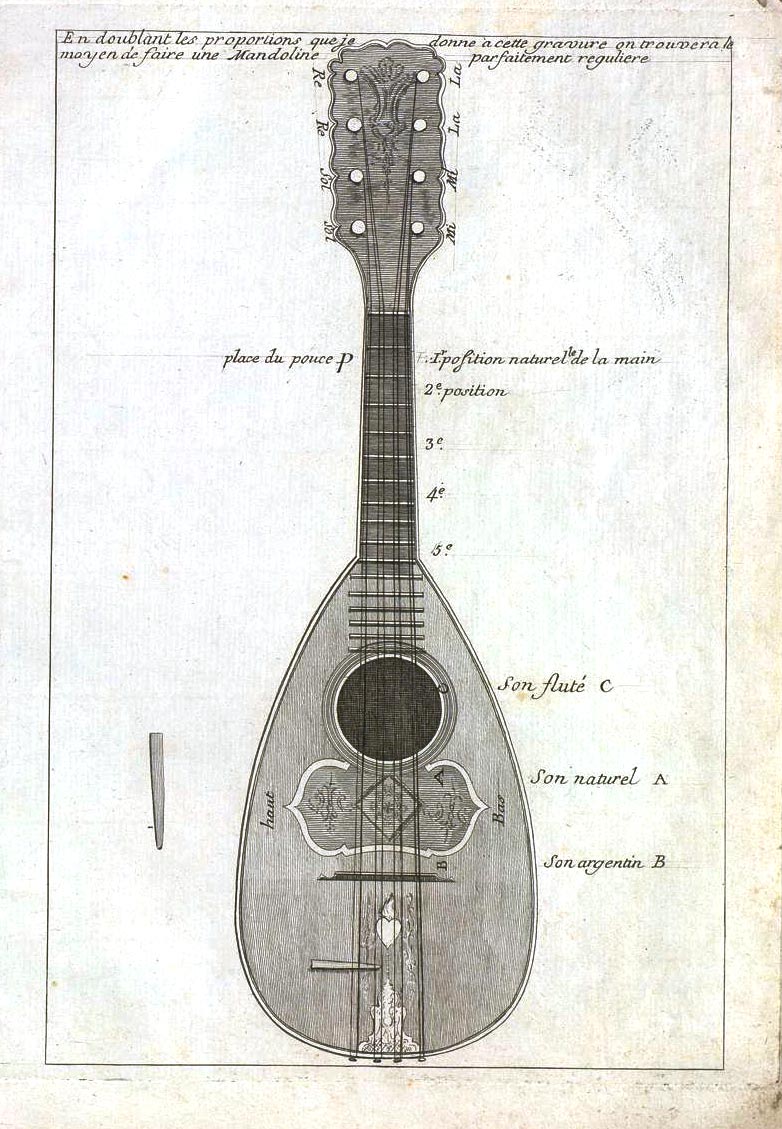

Toutes ces innovations ont permis à la mandoline, pourtant jusque-là boudée par les illustres institutions qu’étaient les quatre conservatoires napolitains, d’attirer l’attention des compositeurs et musiciens et d’entrer à l’orchestre de l’opéra. Signe de la nouvelle estime dont jouissait alors l’instrument, des méthodes pour mandoline apparaissent simultanément à cette époque. L’une des plus connues, celle de Gabriele Leone publiée en 1768 – soit trois ans avant la construction du modèle d’Antonio Vinaccia de la vente du 5 novembre 2022 – présente une gravure du nouvel instrument qui, au regard de celui en vente, ne laisse aucun doute sur le rôle d’Antonio Vinaccia dans l’élaboration de la mandoline napolitaine. Durant la seconde moitié du XVIIIème siècle, ce nouveau type de mandoline fit de nombreux adeptes dans ce qui devint le Royaume des Deux-Siciles. Elle rencontra également un certain succès en France, Allemagne et dans les pays voisins[1]. Ainsi, grâce aux Vinaccia, Naples s’affirma comme la “capitale” de la mandoline et vit l’essor de musiciens professionnels. Véritable reflet de ce succès, un répertoire de musique savante pour mandoline se développa sous la plume de Vivaldi, Verdi, Charpentier, Mozart ou encore Beethoven, qui composèrent pour elle. Du rang d’instrument populaire, elle fut élevée à celui de soliste

[1] Alfred Woll, The Art of Mandolin Making, Welzheim, Mando, 2021, pp17-20.

En bonne partie grâce à Antonio Vinaccia, la mandoline gagna ses lettres de noblesse et conquit une nouvelle clientèle de musiciens professionnels et d’aristocrates. L’instrument fit en effet son entrée dans les cours et salons européens et les femmes, comme de coutume au XVIIIème siècle, en devinrent le principal agent de diffusion. Les dames de l’aristocratie et de la haute bourgeoisie s’éprirent de ce nouvel instrument à la pointe de la modernité, comme en témoigne une riche iconographie. Il faut dire que l’exemple fut donné au plus haut degré de la cour de France par la reine Marie-Antoinette, qui prit pour habitude de faire jouer la mandoline après dîner au Trianon – ce qui ne manqua pas d’attirer la convoitise des laissés-pour-compte[1]. Parallèlement, la fille du roi de Sardaigne et épouse du futur Louis XVIII, Marie-Joséphine princesse de Savoie, choisit de se faire portraiturer en 1777 par Jean-Baptiste André Gautier-Dagoty au côté de sa mandoline.

[1] Lafont d’Aussonne, Mémoires secrets et universels des malheurs et de la mort de la reine de France, Paris, Philippe, 1836

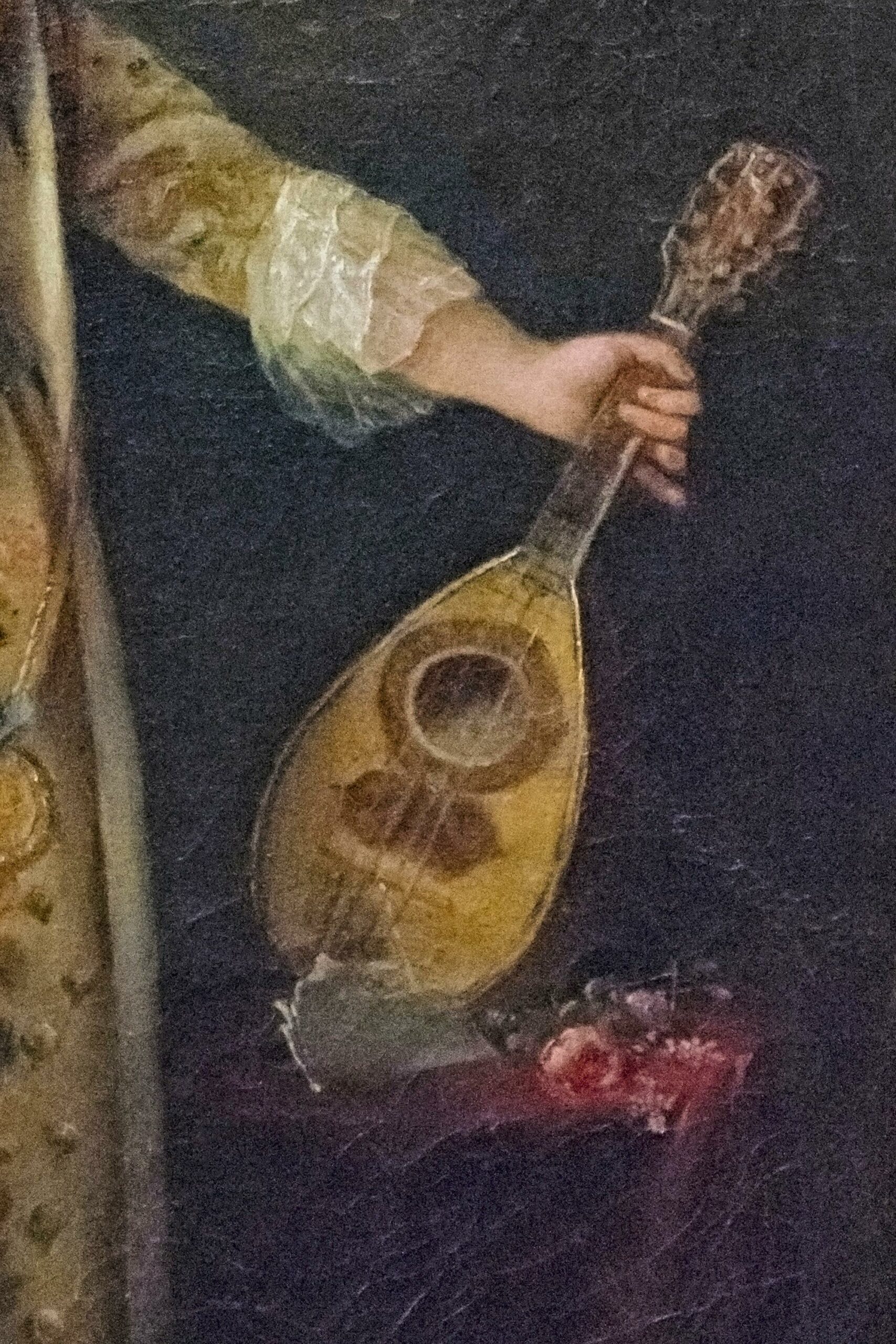

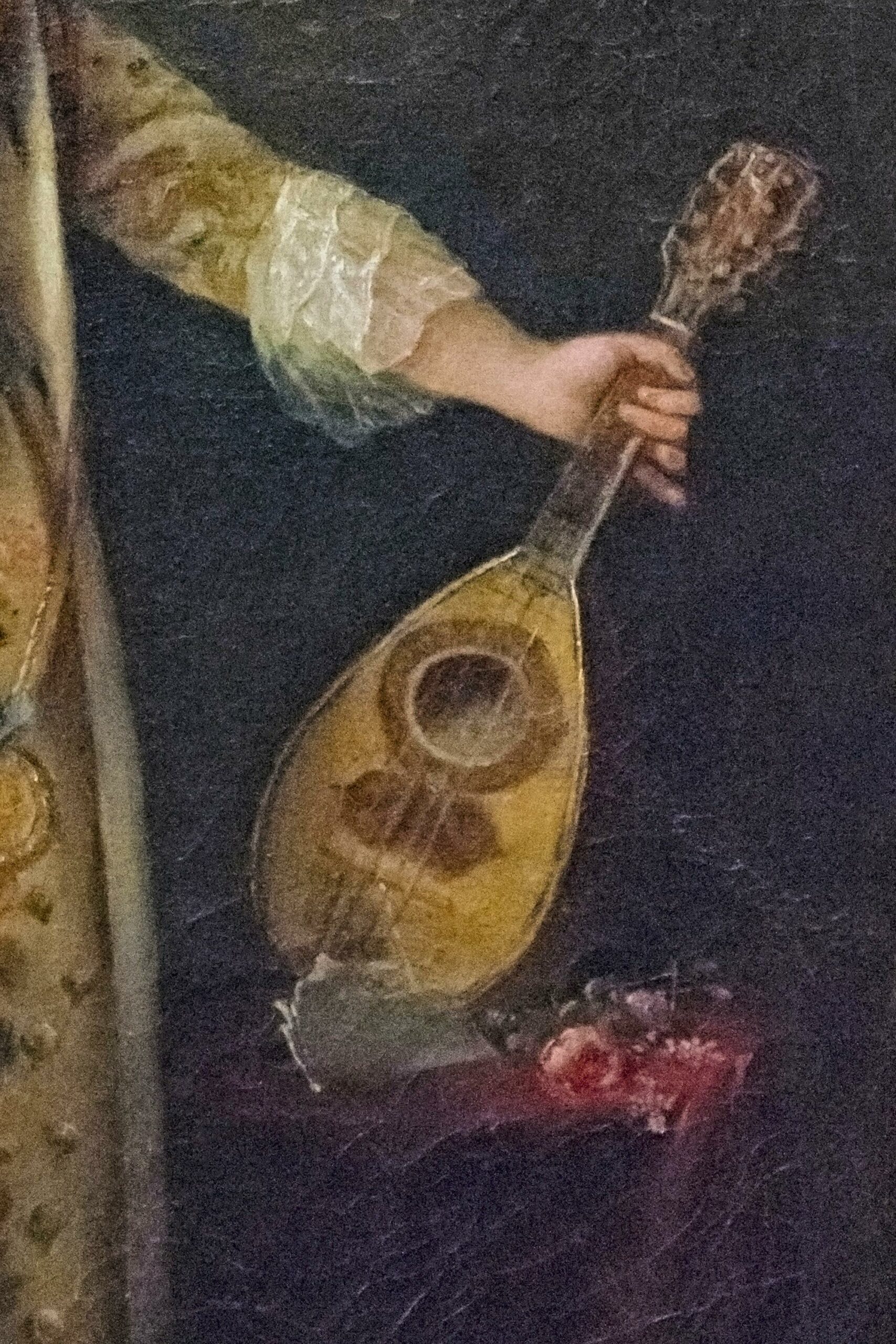

Les témoignages picturaux ne manquent pas pour attester de la nouvelle vogue de la mandoline auprès des dames de qualité. Madame Louis de Chénier – l’épouse du célèbre diplomate de Louis XVI – posa ainsi pour Cazes Fils avec un modèle de mandoline comparable à celui d’Antonio Vinaccia du Musée de la Musique de Paris, daté vers 1770.

La peinture permet également d’observer le changement de statut opéré par l’instrument à la fin du siècle puisqu’en 1755-60, Tiepolo portraiturait une femme aux allures de bohémienne jouant de la mandoline baroque, quand environ vingt ans plus tard, David Martin dépeignait une jeune aristocrate, plectre en main, faisant résonner sa mandoline napolitaine.

Les mandolines d’Antonio Vinaccia furent en partie commandées pour la cour de Charles III[1] (1716-1788) et de son fils Ferdinand Ier (1751-1825), issus de la maison de Bourbon-Siciles, la branche italienne de la maison de Bourbon régnant sur les royaumes de Naples, de Sicile puis des Deux-Siciles. En 1734 et 1735, Charles – l’arrière-petit-fils de Louis XIV – fut consécutivement sacré roi de Naples puis de Sicile, avant de ceindre la couronne d’Espagne en 1759 sous le nom de Charles III, cédant dès lors les royaumes à son troisième fils, Ferdinand – cousin de Louis XVI et de Marie-Antoinette. C’est ce dernier qui est à l’origine de leur unification en 1816 et de la création du royaume des Deux-Siciles, le plus grand État de la péninsule italienne, l’amenant à prendre le nom de Ferdinand Ier roi des Deux-Siciles. A cette époque et principalement grâce à Charles III, Naples connaît une période de renaissance économique et culturelle. Elle devint ainsi l’une des plus importantes villes d’Europe et se rapprocha de la cour de France.

[1] Voir Giovanni de Piccolellis, Liutai antichi e moderni, 1885 ; Wilhelm Heyer, Musikhistorisches Museum in Cöln. Katalog von Georg Kinsky, 1912 ; A. Galante, Giuseppe Accorretti, Ugo Orlandi, Il periodo d’oro del mandolino, 1996

C’est dans ce contexte qu’Antonio Vinaccia fut sollicité par les monarques de son temps afin de réaliser les instruments des membres de leurs différentes cours. En 1912, Heyer signalait ainsi que :

“Les meilleures mandolines du XVIIIe siècle étaient fabriquées par la famille Vinaccia à Naples, à l’instar de Gennaro et ses trois fils Giovanni, Antonio et Vincenzo V. – qui étaient très appréciés en Italie pour leurs instruments d’excellente facture et joliment décorés […]. Les magnifiques mandolines fabriquées par Antonio Vinaccia pour le roi Charles III d’Espagne, aujourd’hui conservées au « Museo spanuolo » de Naples, sont bien connues.”

Traduction libre de Wilhelm Heyer, Musikhistorisches Museum in Cöln. Katalog von Georg Kinsky, 1912, p.214

Le Museo Spagnuolo (ou Musée espagnol de Naples) avait été fondé par Charles III dans les années 1750 et fut également le siège de l’Université de la ville. En 1885, dans son ouvrage sur la lutherie ancienne et moderne, Giovanni de Piccolellis mentionnait déjà que des instruments réalisés par Antonio Vinaccia pour Caroline d’Autriche, Ferdinand IV et Charles II de Bourbon, étaient conservés dans ce musée[1].

[1] Giovanni de Piccolellis, Liutai antichi e moderni, 1885, p. 91

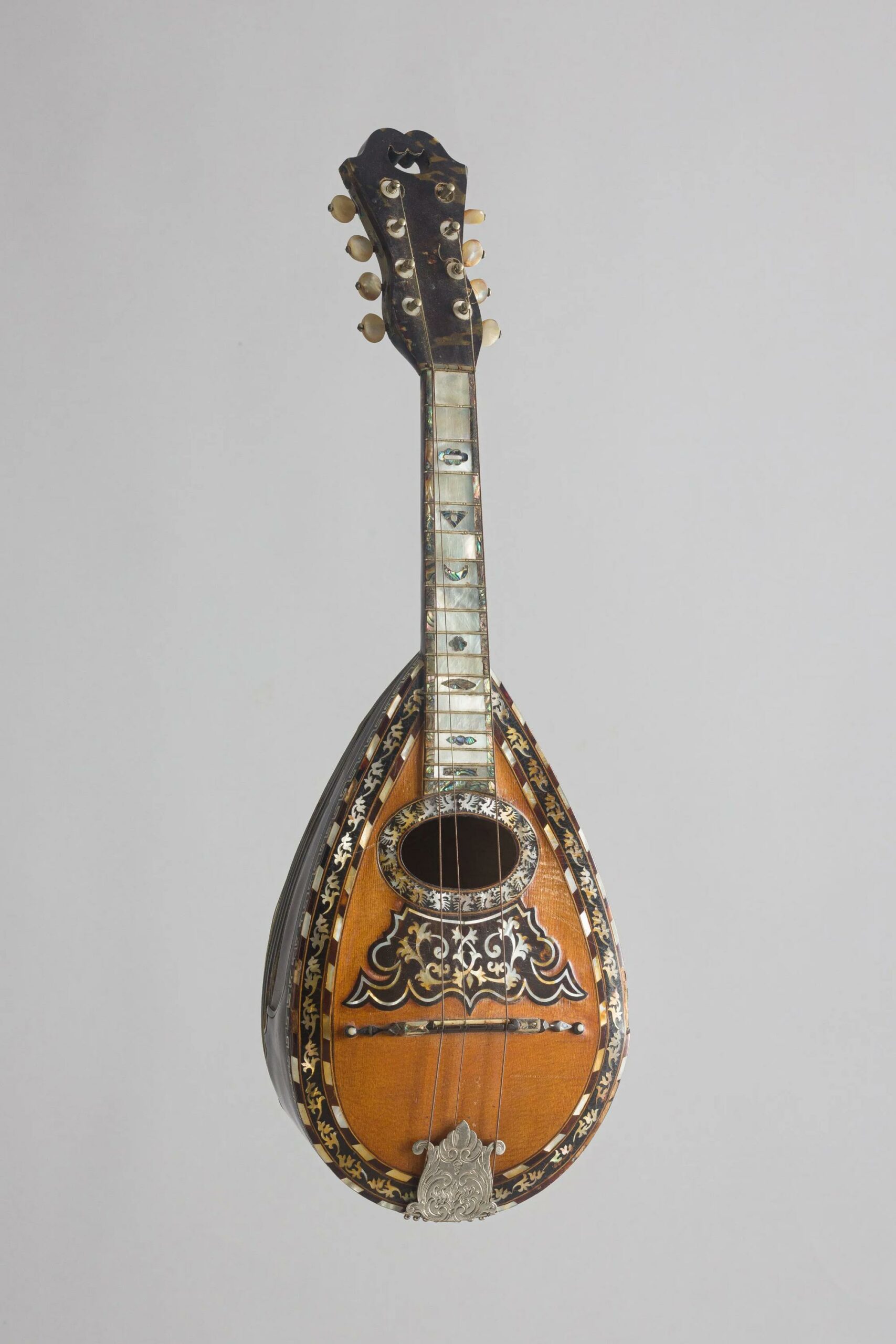

Malheureusement, nous avons perdu la trace des instruments auparavant conservés au Museo Spagnuolo del Palazzo degli Studi – aujourd’hui Musée archéologique de la ville de Naples. Cependant, le degré de raffinement de certaines mandolines d’Antonio Vinaccia, en comparaison avec d’autres modèles beaucoup plus modestes, suggère de nobles provenances. Rappelons qu’au XVIIIème siècle, la préciosité et la finesse des œuvres d’art reflétaient la position sociale de leur commanditaire. En ce qui concerne la mandoline de la vente du 5 novembre 2022 et au regard de la production de Vinaccia, ses éléments décoratifs et son délicat traitement du manche et de la tête – à l’allure et l’élégance peu fréquente -, la placent parmi ses instruments les plus raffinés et nous permettent d’envisager une commande de Cour.

De plus, la comparaison de cet instrument avec des modèles plus rudimentaires apparaissant sur plusieurs portraits de dames de qualité (à l’exemple des tableaux mentionnés plus haut), nous conduit à penser que la mandoline de la vente Vichy Enchères fut réalisée pour une personnalité au moins du même acabit.

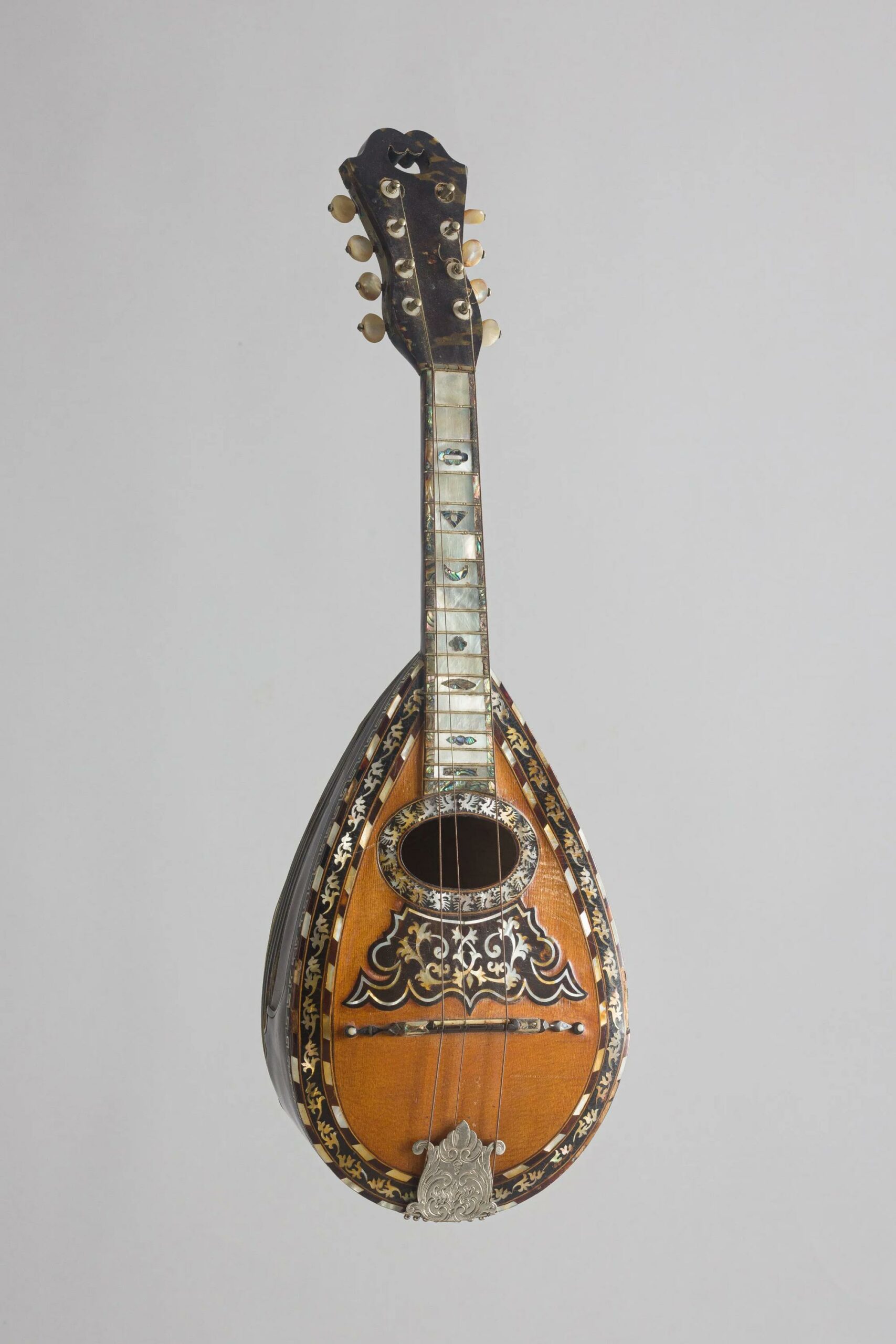

A titre de comparaison, parmi les rares instruments d’Antonio Vinaccia dont nous connaissons la provenance historique, on conserve au Landesmuseum de Stuttgart une mandoline ayant appartenu à la femme de Ferdinand Ier, Marie-Caroline d’Autriche, la reine de Naples et de Sicile et soeur aînée de Marie-Antoinette. Son somptueux décor et ses incrustations d’écailles de tortue et de nacre témoignent indubitablement de la différence de traitement portée à l’instrument en fonction de son propriétaire. Bien que les ornements de la mandoline de la vente Vichy Enchères soient moins développés que ceux de l’instrument de Marie-Caroline d’Autriche, on peut tout à fait présumer que notre mandoline ait appartenu à une personnalité gravitant autour de l’une des cours pour lesquelles œuvra Antonio Vinaccia.

Si la majorité des instruments conçus par Antonio Vinaccia pour des figures de cour sont aujourd’hui méconnus, nous connaissons toutefois un exceptionnel modèle réalisé pour l’un des plus prestigieux commanditaires de l’époque qu’il soit : la fille aînée de Ferdinand Ier des Deux-Siciles et de Marie-Caroline d’Autriche, Marie-Thérèse de Bourbon-Naples[1] – dernière impératrice du Saint-Empire, reine de Germanie, de Bohême et de Hongrie et archiduchesse d’Autriche. Conservé en collection privée, ce chef-d’œuvre du genre est particulièrement intéressant en ce qui nous concerne, puisque c’est le seul à présenter une tête stylistiquement comparable à celle du modèle en vente le 5 novembre 2022.

[1] Giovanni Accornero, Prezioso Strumenti, Illustri Personaggi, Liuteria e Musica tra Seicento e Nocevento in Europa, Edizioni Il Salabue, 2018, pp.156-161

Ces deux têtes sont composées d’une succession d’arcs cintrés et de petits cercles et présentent en leur sommet une fleur stylisée à trois ramifications identiquement divisées, évoquant la fleur de lys, symbole des Bourbon – probablement judicieusement choisi dans le cas de l’instrument de Marie-Thérèse de Bourbon-Naples. Rappelons qu’habituellement, les têtes des instruments de Vinaccia sont plus classiques et trapézoïdales et que seuls de rares modèles, plus raffinés, arborent une tête sophistiquée mais davantage en forme de palmettes. La forme de la tête de l’instrument en vente le 5 novembre 2022 est donc très rare et il n’est pas anodin que l’exemple connu le plus proche soit celui de la mandoline de l’impératrice du Saint-Empire.

Sur le dos, on observe également la même jonction triangulaire entre la tête et le manche, que ce soit sur l’instrument de l’impératrice ou sur celui de la vente du 5 novembre 2022.

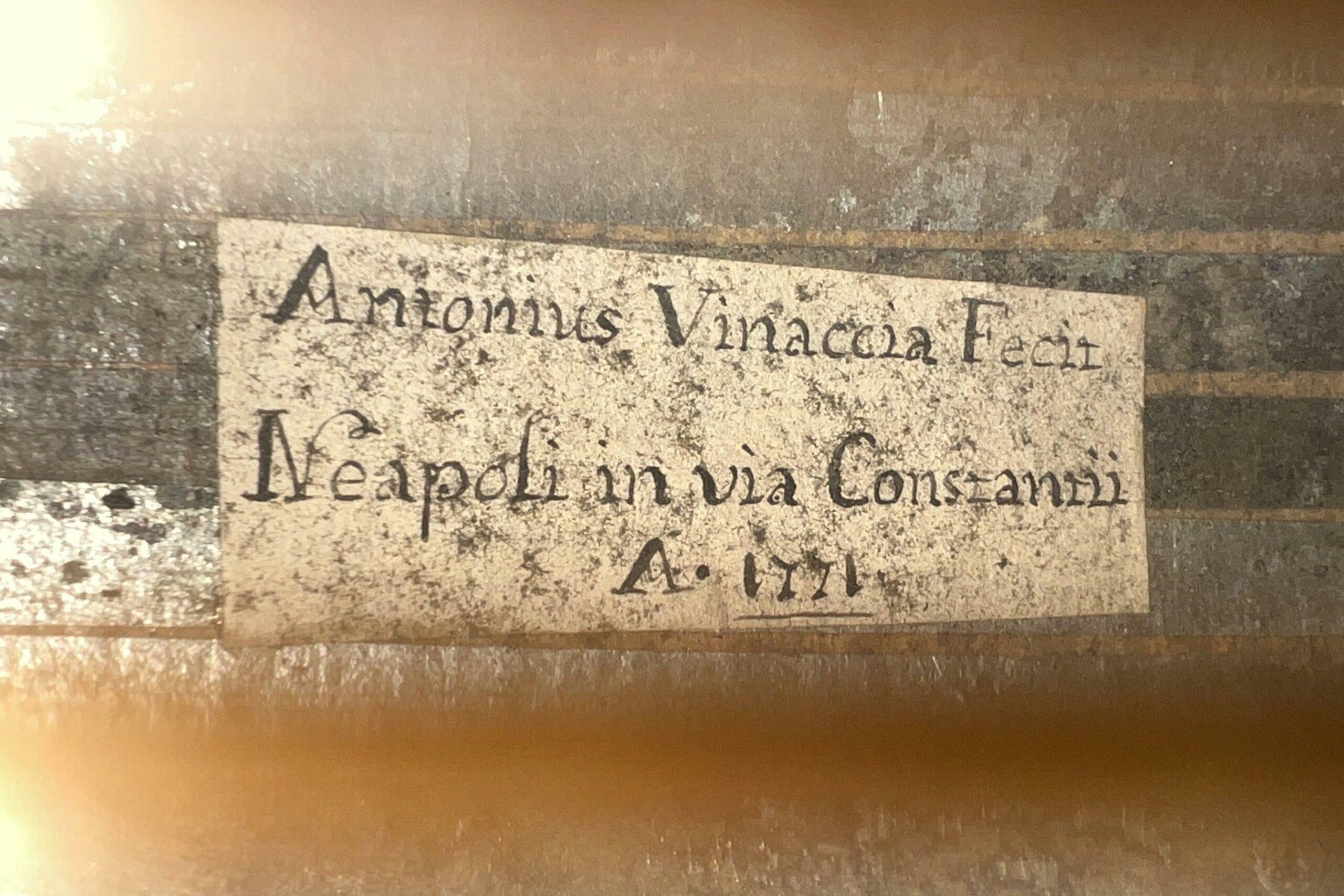

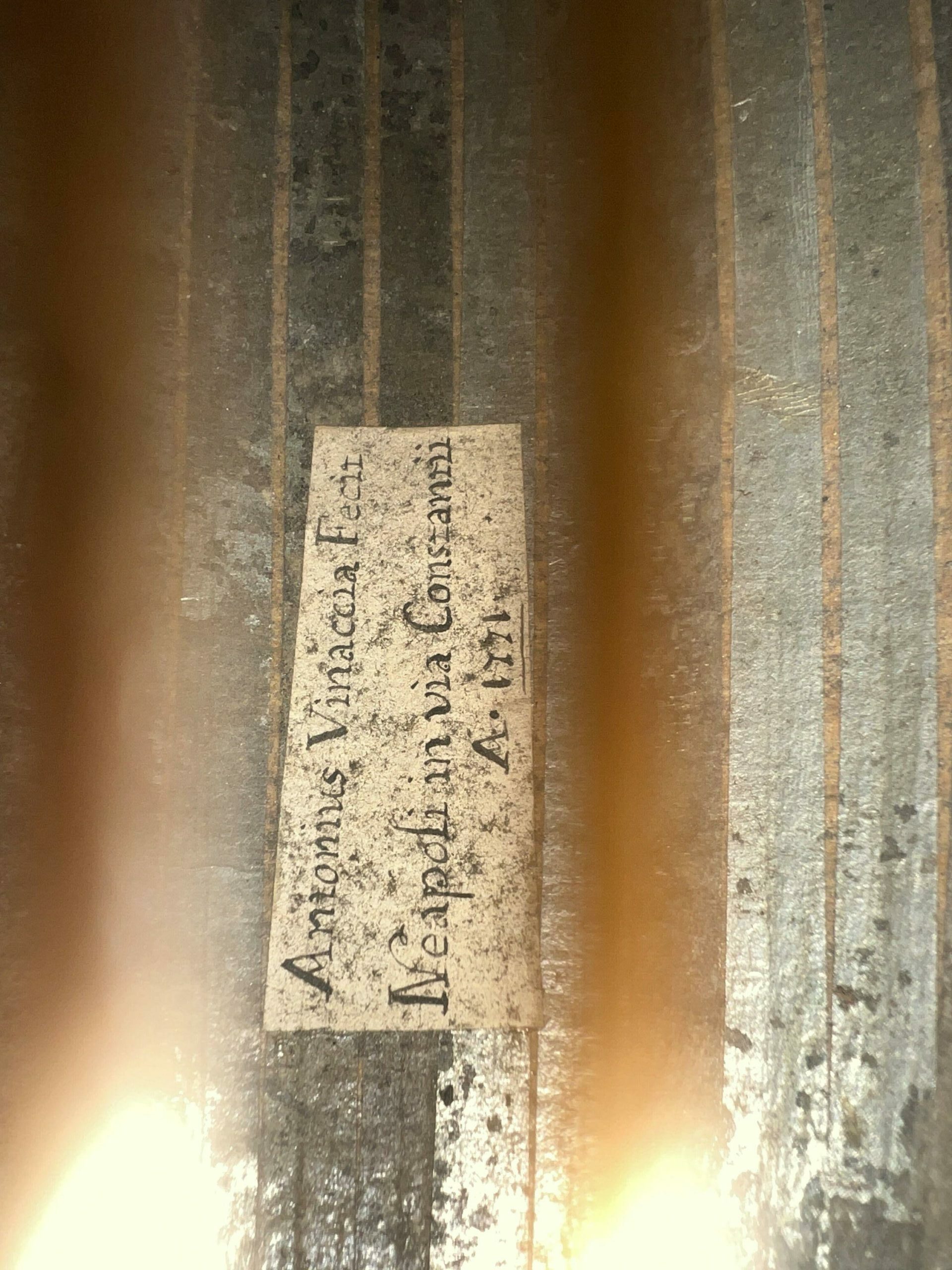

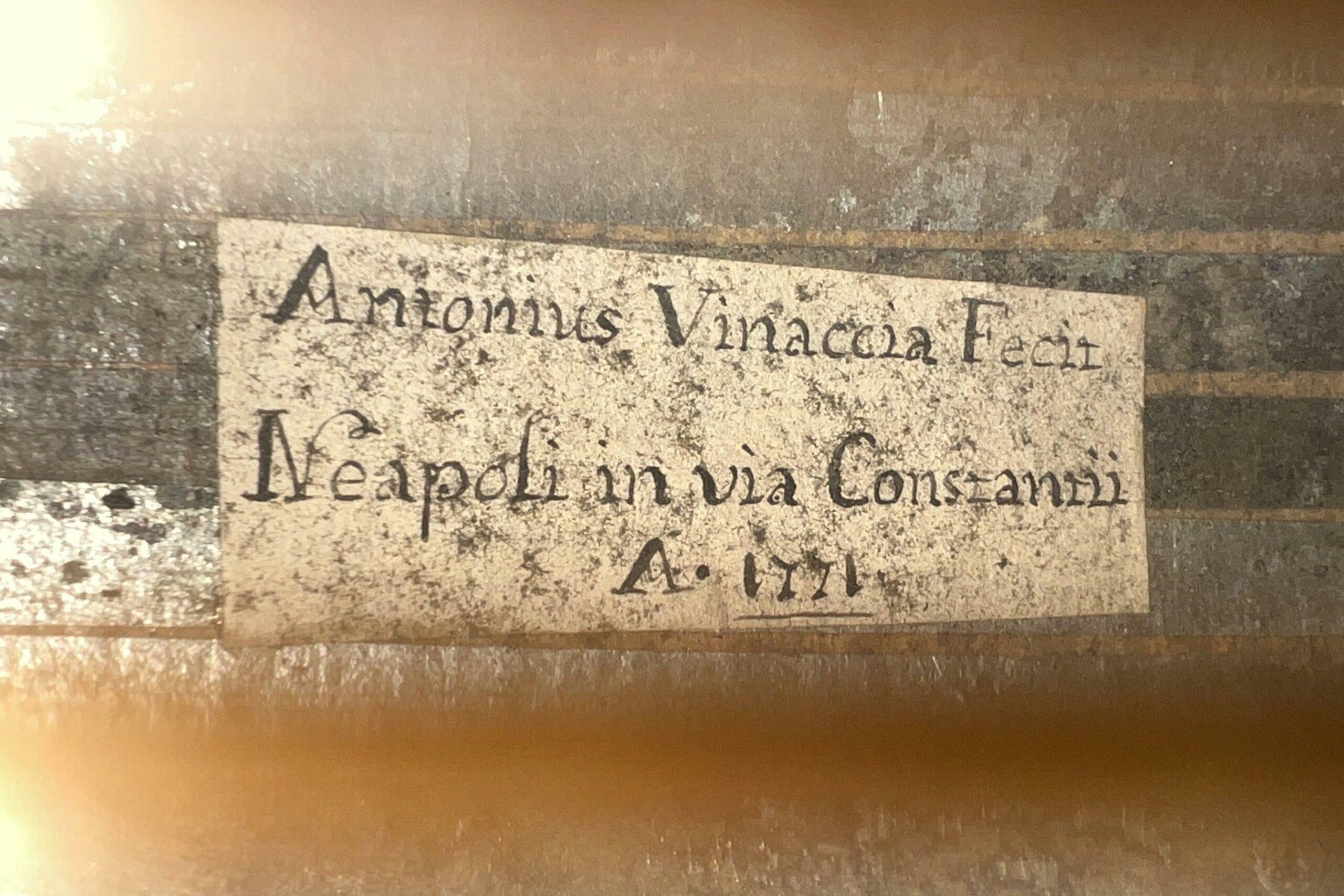

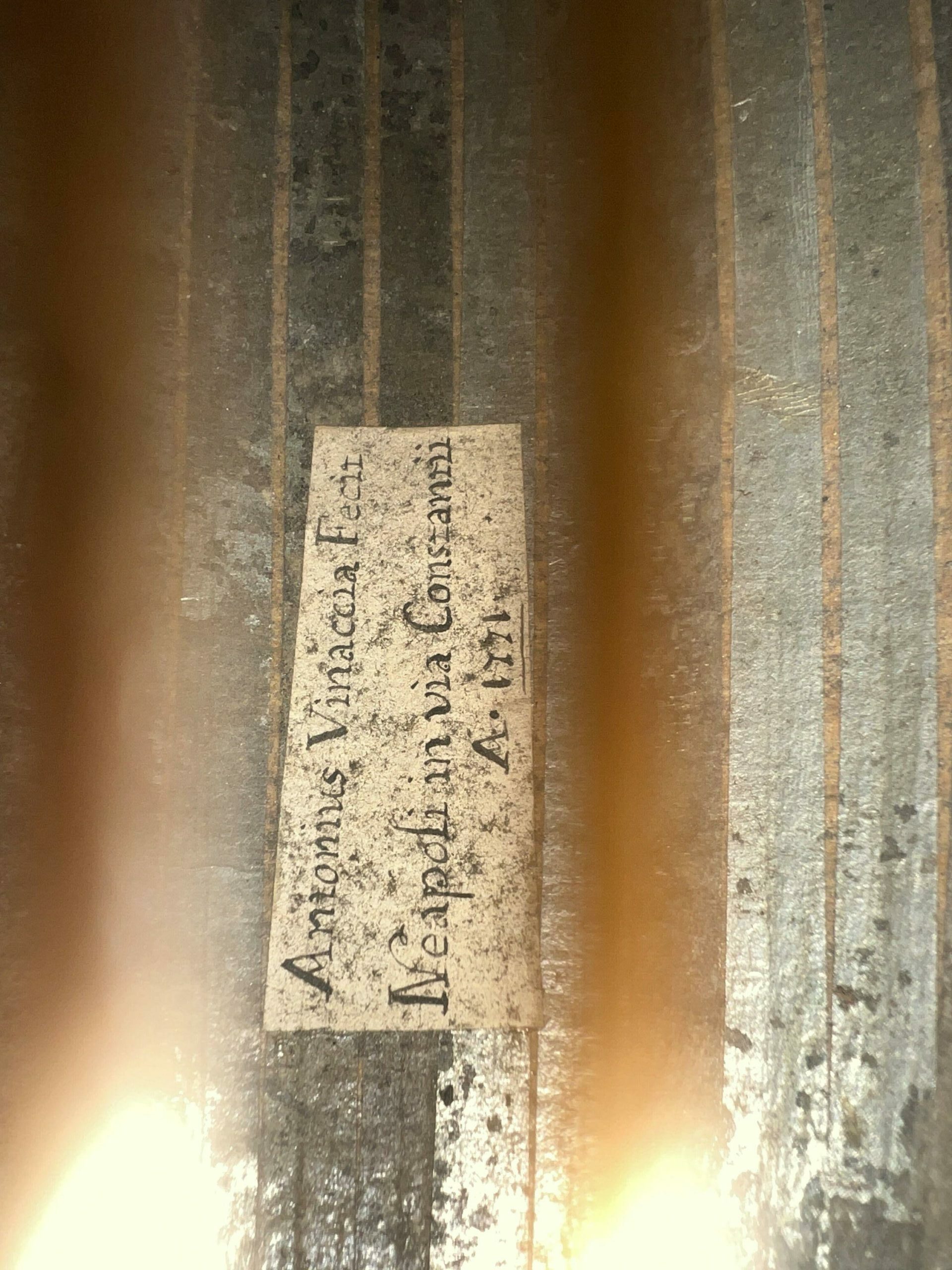

Cette mandoline est également exceptionnelle car il s’agit, à notre connaissance, du seul instrument portant la marque au fer d’Antonio Vinaccia. Apposée de manière apparente dans un cartouche situé sur la brague en-dessous de l’accroche des cordes, elle se compose de la mention suivante :

“ANT. VINACCIA* F. NEAP”.

Cette caractéristique confirme le caractère unique de cette mandoline qui se distinguait déjà par ses ornements et sa remarquable tête. Qu’Antonio Vinaccia appose sa marque précisément sur cet instrument laisse penser que celui-ci avait une importance particulière dans sa production.

Il pourrait également s’agir d’une demande spécifique provenant d’un commanditaire particulièrement exigeant et désireux d’afficher le nom de ce luthier de renom.

Outre la présence de cette marque, l’instrument porte l’étiquette couramment utilisée par Antonio Vinaccia lorsqu’il œuvrait Via Constantii à Naples. Rappelons en effet qu’après avoir travaillé dans l’atelier de son père, rue Catalana à Naples, notre luthier déménagea en 1768 Via Constantii. Daté 1771, l’instrument confirme ces éléments biographiques par son étiquette interne inscrite : “Antonius Vinaccia Fecit / Neapoli in via Constantii / A. 1771”.

Cette mandoline a fait l’objet d’un travail délicat et raffiné, en témoignent ses éléments décoratifs et matériaux. Comme on peut l’observer sur ses plus beaux modèles, l’intérieur de l’instrument est recouvert de bandes d’argent collées verticalement.

Sa table d’harmonie est finement décorée d’incrustations de nacre et d’écailles de tortue que l’on retrouve également sur le manche, la tête et la plaque de protection. Sous la nacre, on peut observer des feuilles d’or plaquées dans le but d’apporter luminosité et préciosité à l’instrument.

Sur la base de la table, au niveau de l’accroche des cordes, se déploie un motif floral incrusté de points en corail que l’on retrouve également sur le manche et la tête. Comble du raffinement, ces ornements sont rehaussés par des incisions donnant du relief et de la précision aux différents éléments figurés.

“Le travail en piqué, particulièrement utilisé à Naples, est une technique qui consiste à insérer dans une plaque d’écaille de tortue de petites et fines décorations en or ou autres métaux. Pour ce faire, on ramollissait l’écaille de tortue dans de l’eau bouillante et de l’huile d’olive, puis on y pressait les décorations.”

Traduction libre de Giovanni Accornero, Prezioso Strumenti, Illustri Personaggi, Liuteria e Musica tra Seicento e Nocevento in Europa, Edizioni Il Salabue, 2018, p.159

Signalons enfin qu’un seul et même filet de nacre se prolonge sur le pourtour de la table, du manche et de la tête. La caisse est constituée de vingt-et-unes côtes creuses en érable ondé, chacune flanquée de filets d’os et d’ébène.

Le dos de la mandoline est quant à lui recouvert d’une brague finement ciselée en ronde bosse d’une rare finesse dans la production de Vinaccia. En effet, une rapide comparaison avec les modèles conservés au Musée de la Musique confirme le haut degré de raffinement de la brague de l’instrument en vente.

En outre, la comparaison de ce décor avec une très remarquable mandoline ayant appartenu à la princesse della Cisterna, Maria Beatrice Barbiano di Belgiojoso d’Este (1763-1782), est édifiante puisqu’elle rend compte d’un traitement et répertoire ornemental similaire composé de formes géométriques et de motifs végétaux.

Maria Beatrice descendait de la branche cadette de la dynastie des ducs de Modène. Elle était la fille du prince Alberico Barbiano de Belgioioso et de la princesse Ricciarda d’Este, et fut mariée à l’un des membres les plus importants de la cour de Savoie, le prince Giuseppe Alfonso Dal Pozzo de Cisterna[1]. Enfin, et cela est assez rare pour être souligné, notre instrument conserve son chevalet d’origine finement ouvragé, en bois avec un filet d’os, stylistiquement comparable à celui de la mandoline de la princesse.

[1] Giovanni Accornero, Prezioso Strumenti, Illustri Personaggi, Liuteria e Musica tra Seicento e Nocevento in Europa, Edizioni Il Salabue, 2018, pp.150-159

Cette mandoline d’Antonio Vinaccia est seulement le deuxième modèle connu conjuguant des motifs floraux typiquement baroques avec des formes géométriques propres au nouveau goût néoclassique. En effet, ce répertoire stylistique de transition entre le baroque et le néoclassicisme est également présent sur l’instrument de la princesse Maria Beatrice Barbiano di Belgioioso d’Este (cf paragraphe ci-dessus).

Ces éléments décoratifs sont particulièrement visibles sur le dos des deux instruments, au niveau de la brague, et se composent d’entrelacs végétalisant à la sinuosité entrecoupée par des angles droits, dessinant des formes géométriques évoquant le motif antique de la clé grecque.

Ce répertoire ornemental s’inscrit pleinement dans le contexte artistique de l’époque des Lumières – celui du néoclassicisme qui émerge dans les années 1750 pour atteindre son apogée vers 1780. On le retrouve ainsi sur différentes effigies de Charles III d’Espagne, à l’exemple d’une gravure de Giovanni Morghen présentant le profil du roi dans un médaillon relié à son pendant par des formes évoquant également la clé grecque.

Cette rigueur néoclassique est aussi perceptible sur notre mandoline au niveau de la rosace à larges bandes d’écailles de tortue, divisées symétriquement par des inclusions de nacre. En outre, le portrait en pied de Charles III réalisé vers 1765 par le chef de file de la peinture néoclassique, Anton Raphaël Mengs, le dépeint devant ses armoiries encadrées d’une guirlande composée de palmettes, feuilles d’acanthes et coquilles – autant de motifs dont s’inspire Vinaccia pour la décoration de la mandoline en vente le 5 novembre 2022 à Vichy Enchères.

Enfin, signalons une intéressante gravure de Filippo Morghen conservée au Prado et figurant Charles III devant tout un attirail symbolique, dont un casque à visage barbu, qui n’est pas sans rappeler les deux grotesques affrontés se fondant dans le décor de la table de notre mandoline.

Principalement grâce aux Vinaccia, Naples devint le centre majeur de production des mandolines aux XVIIIème et XIXème siècles. Malgré l’existence d’autres foyers de création, la mandoline napolitaine parvint à occulter les autres modèles. Naples s’affirma en tant que capitale incontestée de la mandoline et les instruments de la famille Vinaccia acquirent et conservèrent une haute réputation à l’international.

“[The] instruments built by the Vinaccia family still had the highest international reputation. The core of the family business had occupied the same premises in the rua Catalana since the mid-eighteenth century, until increased demand finally forced most of them to relocate to a larger building in the 1890s”

Paul Sparks, The Classical Mandolin, Oxford University Press, 2005

Antonio Vinaccia fut certes l’un des principaux représentants de la dynastie, son petit-fils Pasquale Vinaccia (1806-1882) fit basculer l’instrument dans la modernité au XIXème siècle. En effet, autour de 1830, il redessina complètement la mandoline en introduisant des techniques de construction novatrices. Il s’intéressa notamment aux mécaniques et aux cordes en acier haute tension qui furent par la suite généralement utilisées. Il étendit également la touche à 17 frettes, augmentant la gamme de l’instrument. Parmi les premiers luthiers à développer la mandoline aux côtés des Vinaccia au XVIIIème siècle, il faut citer Luigi Salsedo, également de Naples, un luthier de premier rang dont le modèle “is somewhat smaller than the Vinaccia, and the build is a little heavier, but the workmanship is admirable – the tone and intonation alike are good.”[1]

[1] Richard Harrison, “The mandoline”, in The Bazaar, The Exchange and Mart, 3 janv. 1894, pp.24-25.

Par ailleurs, durant les XVIIIème et XIXème siècles, on compte parmi les fabricants les plus importants de mandoline napolitaine aux côtés des Vinaccia, les Calace, Fabricatore ou encore Filano. A partir de 1770, on constate une tendance à l’augmentation du volume de la caisse des instruments, notamment perceptible dans la production de Giovanni Battista Fabricatore. Le 5 novembre 2022, vous pourrez notamment retrouver une belle mandoline de ce luthier, réalisée en 1789 et provenant de la collection Calas. Au cours du XIXème, les Vinaccia firent également face à de sérieux concurrents comme les Calace.

Musiciens et luthiers, Raffaele (1863-1934) et son frère Nicola Calace (1859-1923) introduisirent des améliorations dans les techniques de construction qui modernisèrent la mandoline, allongeant notamment la touche et augmentant l’étendue de l’instrument. Le style napolitain de construction des mandolines fut adopté et développé par d’autres luthiers, notamment à Rome avec Giovanni De Santis, Giovanni Battista Maldura ou Luigi Embergher. Ce dernier, particulièrement inventif, réalisa notamment une mandoline cubiste totalement subversive dans le domaine et unique modèle connu. Véritable œuvre d’art, l’instrument a été vendu à Vichy Enchères en 2012.

Après avoir été à la mode dans les cours européennes au XVIIIème siècle, la mandoline devint davantage populaire au XIXème siècle, symbolisant la sérénade amoureuse. Toutefois, le mécénat de la reine d’Italie Marguerite de Savoie contribua à la revalorisation de l’instrument et à sa diffusion, avec la création de plusieurs orchestres. Une fois de plus, c’est aux Vinaccia qu’une reine fera appel pour la réalisation de ses instruments personnels… Rendez-vous le 5 novembre 2022 pour la vente de cette exceptionnelle mandoline d’Antonio Vinaccia.

On 5 November 2022, Vichy Enchères invites you to the sale of this exceptional mandolin by Antonio Vinaccia. It is dated 1771 and is the only known example bearing this maker’s brand. It is also unique for its lavish decoration and refinement, and is testimony to the golden age of the instrument at the court of the Bourbon-Two Sicilies.

If there is one family that has marked the history of the mandolin, it is the Vinaccias. This dynasty of makers contributed for two centuries to the development and fame of the instrument. Their work changed the way in which the instrument was considered, and virtuosos and wealthy patrons really began to take an interest in it during the last third of the 18th century. The history of the mandolin is linked to that of the lute, which was very popular in medieval Western culture, but whose origin is oriental. The Arabs discovered the Persian lute in the 6th century, and the instrument was introduced to Europe via Moorish Spain. During the 17th century, several instruments of the lute family, predating the mandolin and available in different sizes, were already in use. These first mandolins, called baroque mandolins or mandolino, were first created in Milan and distinguishable from the lutes by their smaller size, their more curved body, their shorter neck with frets, and also by their head, which was no longer « broken” backward like that of the lute.

Their body is almond-shaped and the instrument has a characteristic “comma” shaped peg box. The Milanese mandolin usually had six gut courses, played with the fingers and tuned in fourths and a third. It was only during the second half of the 18th century, and mainly in Naples, that the baroque instrument evolved. These new instruments were called Neapolitan mandolins to distinguish them from the Milanese ones. It is generally accepted that this type of instrument was developed by the Vinaccia family, and especially by Gennaro and Antonio. One of the oldest Neapolitan examples to have come down to us is an instrument from 1759 labelled “Antonius Vinaccia filius January”, kept in the museum of the University of Edinburgh, which is of rather austere appearance, and devoid of ornamentation.

In his article on the Vinaccia family, published in 2017 in issue 87 of GuitArt magazine, Raffaele Carpino provide an overview of the different members of the family[1]. It is generally accepted that this dynasty of makers goes back to Gennaro [I] Vinaccia (c.1710 – c.1781), active from 1734, and a likely pupil of Gagliano. His output included guitars, violins and mandolins, and so did his sons’. Gennaro had three sons who were also makers: Antonio (active around 1753-1785), Giovanni (active around 1750-1780) and Vincenzo (active around 1752-1795).

[1] Raffaele Carpino, “La famiglia Vinaccia. Storia e approfondimenti dalle origini al XIX sec.”, GuitArt, n°87, 2017

Antonio Vinaccia is considered the most skilled and successful maker of the dynasty. His mandolins were highly sought after by the most prestigious patrons during his lifetime. Like his father, he in turn had three sons who became makers: Nicola (active around 1770-1808), Mariano (active around 1775-1810) and Gaetano [I] (active around 1779-1848), whose production included mainly guitars. We should finally mention Pasquale, the son of Gaetano, active from approximately 1828 to 1883, whose work had a great influence on the history of the modern mandolin.

“The Vinaccia family have undoubtedly been the greatest artists in the construction of mandolines. […] Their workmanship and designs place them considerably beyond the reach of their opponents. The tone and finish of their mandolines are irreproachable. A real Vinaccia fratelli is the “Strad” of mandolins.”

Richard Harrison, “The mandoline”, in The Bazaar, The Exchange and Mart, 3 janv. 1894, pp.24-25.

The Vinaccias were great innovators and played a key role in the history of the mandolin. Gennaro and Antonio were among the first to modify the proportions of the baroque instrument. Antonio Vinaccia’s mandolins – considered by many to be the finest – are slightly larger than Gennaro’s. In general, this new model of mandolin was distinguishable by its widened front and its higher bridge (it was previously positioned very low). Between the bridge and the sound hole, there was now a scratch plate made of tortoiseshell or wood, in order to protect the instrument from damage. Indeed, it was now played with a plectrum because its gut strings had been replaced by metallic ones, and tuned in fifths like the violin – making it easier to play it for most musicians. The body was constructed from bent wood called “rib”, and the soundboard – which was previously flat – tilted from the bridge, at its maximum width. The head, which was so distinctive in Milanese mandolins, became trapezoidal, like those of guitars. Finally, additional frets were added to extend the range of the instrument.

All these innovations allowed the mandolin, which until then had been shunned by the illustrious institutions that were the four Neapolitan conservatories, to attract the attention of composers and musicians and to enter the opera orchestra. Several methods for the mandolin appeared simultaneously at this time, a sign of the new esteem in which the instrument was held. Amongst the best known, that of Gabriele Leone, published in 1768 – i.e. three years before the completion of Antonio Vinaccia’s instrument in the sale of 5 November 2022 – includes a print of the new instrument, which, when compared to the instrument on sale, leaves no doubt as to the role of Antonio Vinaccia in the development of the Neapolitan mandolin. During the second half of the 18th century, this new type of mandolin attracted many followers in what became the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. It also met with some success in France, Germany and their neighbouring countries[1]. Therefore, thanks to the Vinaccias, Naples asserted itself as the capital of the mandolin and contributed to the rise of professional musicians on this instrument. A true reflection of this success is the repertoire of scholarly music for mandolin composed by Vivaldi, Verdi, Charpentier, Mozart and even Beethoven. Under their pen, it rose from a popular instrument to that of a soloist.

[1] Alfred Woll, The Art of Mandolin Making, Welzheim, Mando, 2021, pp17-20.

Thanks in large part to Antonio Vinaccia, the mandolin won its letters of nobility and conquered a new clientele of professional musicians and aristocrats. The instrument entered European courts and salons, and quickly spread within these circles through women, as was the custom in the 18th century. Ladies of the aristocracy and the upper middle class fell in love with this new instrument at the forefront of modernity, as evidenced by a number of paintings of that period. The trend was set at the highest level of the Court of France by Queen Marie-Antoinette, who was in the habit of playing the mandolin after dinner at the Trianon – which attracted envy from those left behind[1]. At the same time, the daughter of the King of Sardinia and wife of the future Louis XVIII, Marie-Joséphine Princess of Savoy, chose to be portrayed in 1777 by Jean-Baptiste André Gautier-Dagoty alongside her mandolin.

[1] Lafont d’Aussonne, Memoires secrets et universels des malheurs et de la mort de la reine de France, Paris, Philippe, 1836

There is no shortage of paintings attesting to the new vogue for the mandolin amongst ladies of rank. Madame Louis de Chénier – the wife of the famous diplomat of Louis XVI – posed for Cazes Fils with a mandolin similar to the one by Antonio Vinaccia in the Musée de la Musique in Paris, dating from around 1770.

The painting also highlights the change in status of the instrument at the end of the century compared to the period 1755-60; Tiepolo portrayed a woman of bohemian appearance playing the baroque mandolin, while, approximately 20 years later, David Martin depicted a young aristocrat, plectrum in hand, playing her Neapolitan mandolin.

Some of Antonio Vinaccia’s mandolins were commissioned by the court of Charles III[1] (1716-1788) and his son Ferdinand I (1751-1825), from the House of Bourbon-Two Sicilies, the Italian branch of the House of Bourbon that reigned over the kingdoms of Naples, Sicily and then the Two Sicilies. Charles – the great-grandson of Louis XIV – was crowned King of Naples in 1734, and of Sicily in 1735, before being crowned King of Spain in 1759 under the name of Charles III, therefore ceding the kingdoms to his third son, Ferdinand – cousin of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. It was Ferdinand who led to their unification in 1816 and the creation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, the largest state on the Italian peninsula, and in doing so became Ferdinand I, King of the Two Sicilies. At that time and mainly thanks to Charles III, Naples experienced a period of economic and cultural renaissance. It became one of the most important cities in Europe and formed close ties with the court of France.

[1] Voir Giovanni de Piccolellis, Liutai antichi e moderni, 1885 ; Wilhelm Heyer, Musikhistorisches Museum in Cöln. Katalog von Georg Kinsky, 1912 ; A. Galante, Giuseppe Accorretti, Ugo Orlandi, Il periodo d’oro del mandolino, 1996

It is in this context that Antonio Vinaccia was asked by the monarchs of his time to make instruments for various court members. In 1912, Heyer pointed out that:

“The best 18th century mandolins were made by the Vinaccia family in Naples, like Gennaro and his three sons Giovanni, Antonio and Vincenzo V. – who were highly regarded in Italy for their exquisitely crafted and beautifully decorated instruments […]. The magnificent mandolins made by Antonio Vinaccia for King Charles III of Spain, now housed in the « Museo spanuolo » in Naples, are well known”

Traduction libre de Wilhelm Heyer, Musikhistorisches Museum in Cöln. Katalog von Georg Kinsky, 1912, p.214

The Museo Spagnuolo (aka the Spanish Museum of Naples) was founded by Charles III in the 1750s and was also the seat of the city’s university. In 1885, in his book on ancient and modern violin making, Giovanni de Piccolellis mentioned that instruments made by Antonio Vinaccia for Caroline of Austria, Ferdinand IV and Charles II of Bourbon, were already kept in this museum[1].

[1] Giovanni de Piccolellis, Liutai antichi e moderni, 1885, p. 91

Unfortunately, we have lost track of the instruments previously kept in the Museo Spagnuolo del Palazzo degli Studi – now the Archaeological Museum of the City of Naples. However, the degree of refinement of certain Antonio Vinaccia mandolins, in comparison with other much more basic models, suggests a noble provenance. It is worth remembering that in the 18th century, the richness of ornamentation and the refinement of works of art reflected the social position of their patron. When compared to the rest of Vinaccia’s output, the mandolin in the sale of 5 November 2022, with its decorative elements and its delicate treatment of the neck and the head – which have a distinctive appearance and elegance – can be counted amongst his most refined instruments and therefore could have been a court commission.

Moreover, the comparison of this instrument with more basic examples featured on several portraits of ladies of rank (such as the paintings mentioned above), leads us to believe that the mandolin in the Vichy Enchères sale was made for a person of at least equal social status.

As another point of comparison, amongst the rare instruments by Antonio Vinaccia whose historical provenance we know, there is a mandolin in the Landesmuseum in Stuttgart that belonged to the wife of Ferdinand I, Maria-Carolina of Austria, the Queen of Naples and Sicily and older sister of Marie-Antoinette. Its sumptuous decoration and inlays of tortoiseshell and mother-of-pearl undoubtedly attest to the level of ornamentation of instruments depending on its owner. Although the ornamentation of the mandolin in the Vichy Enchères sale is less elaborate than that of Marie-Caroline of Austria’s instrument, it is not unreasonable to presume that our mandolin belonged to a member of the high classes for which Antonio Vinaccia worked.

While little is known today of the majority of instruments made by Antonio Vinaccia for court members, we do know of an exceptional example made for one of the most prestigious patrons of the time: the eldest daughter of Ferdinand I of the Two Sicilies and Marie-Caroline of Austria, Marie-Thérèse of Bourbon-Naples[1] – last Empress of the Holy Empire, Queen of Germany, Bohemia and Hungary and Archduchess of Austria. Kept in a private collection, this masterpiece is particularly interesting to us since it is the only mandolin to feature a head stylistically comparable to that of the example in the sale on 5 November 2022.

[1] Giovanni Accornero, Prezioso Strumenti, Illustri Personaggi, Liuteria e Musica tra Seicento e Nocevento in Europa, Edizioni Il Salabue, 2018, pp.156-161

Both these heads feature a series of curved arches and small circles and, at their top, a stylized flower with three equal ramifications, reminiscent of the fleur-de-lys, symbol of the Bourbons – which was a judicious choice in the case of the instrument of Marie-Thérèse of Bourbon-Naples. It is worth remembering that, usually, the heads of Vinaccia instruments are more traditional and trapezoidal and that only rare, more refined, examples feature a more sophisticated, and palm-shaped, head. The shape of the head of the instrument for sale on 5 November 2022 is therefore very unusual, and it is not insignificant that the closest known example is that of the mandolin of the Empress of the Holy Empire. Also, at the back, both the Empress’s instrument and the one in the 5 November 2022 sale have the same triangular joint between the head and the neck.

Cette mandoline est également exceptionnelle car il s’agit, à notre connaissance, du seul instrument portant la marque au fer d’Antonio Vinaccia. Apposée de manière apparente dans un cartouche située sur la brague en-dessous de l’accroche des cordes, elle se compose de la mention suivante :

“ANT. VINACCIA* F. NEAP”.

This brand confirms the unique character of this mandolin, which is already distinctive due to its ornaments and remarkable head. The fact that Antonio Vinaccia decided to brand this instrument suggests that it had a particular importance in his production.

It could also have been an express request from a very particular patron who wanted the name of this renowned maker to appear on the instrument.

In addition to the presence of this brand, the instrument bears the label commonly used by Antonio Vinaccia when he worked via Constantii in Naples. It is worth remembering that after working in his father’s workshop, rua Catalana in Naples, he moved to via Constantii in 1768. The instrument, which is dated 1771, corroborates these facts as its label reads: “Antonius Vinaccia Fecit / Neapoli in via Constantii / A. 1771”.

This mandolin features delicate and refined work, which is most in evidence in its decorative elements and the materials used. As is the case with the most beautiful examples by this maker, the inside of the instrument is covered with silver strips glued vertically.

Its front is finely decorated with mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell inlays that are also found on the neck, headstock and pick guard. Under the mother-of-pearl, gold leaf plating was applied in order to bring luminosity and preciousness to the instrument.

The lower part of the front, near the string pegs, features a floral motif encrusted with coral dots that can also be found on the neck and the headstock. To elevate these ornaments even further, they are enhanced by incisions giving relief and precision to the various figurative elements.

“Piqué work, which was particularly typical of Naples, is a technique that consists of inserting small and fine decorations in gold or other metals into a plate of tortoiseshell. This was done by softening the tortoiseshell in boiling water and olive oil, then pressing the decorations into it.”

Traduction libre de Giovanni Accornero, Prezioso Strumenti, Illustri Personaggi, Liuteria e Musica tra Seicento e Nocevento in Europa, Edizioni Il Salabue, 2018, p.159

Finally, a single strip of mother-of-pearl extends around the edge of the front, the neck and the headstock. The body is made up of twenty-one concave curly maple ribs, separated from each other by bone and ebony purfling.

The back of the mandolin is covered with a finely carved ‘in the round’ motif of an intricacy unusual in Vinaccia’s production. Indeed, a quick comparison with other examples kept at the Musée de la Musique highlights the high degree of refinement of the decoration of the instrument on sale.

A further comparison of this decoration with that of a very remarkable mandolin having belonged to Princess della Cisterna, Maria Beatrice Barbiano di Belgiojoso d’Este (1763-1782), is most enlightening since they feature similar ornamentation, both in extent and style, including geometric shapes and floral motifs.

Maria Beatrice descended from the younger branch of the dynasty of the Dukes of Modena. She was the daughter of Prince Alberico Barbiano de Belgioioso and Princess Ricciarda d’Este, and was married to one of the most important members of the Savoy court, Prince Giuseppe Alfonso Dal Pozzo de Cisterna[1]. Finally, and this is worth pointing out as it is very rare, the instrument retains its finely crafted original bridge, in wood with a bone purfling strip, stylistically similar to that of the Princess’s mandolin.

[1] Giovanni Accornero, Prezioso Strumenti, Illustri Personaggi, Liuteria e Musica tra Seicento e Nocevento in Europa, Edizioni Il Salabue, 2018, pp.150-159

This mandolin by Antonio Vinaccia is only the second known example combining typically Baroque floral motifs with geometric shapes specific to the new neoclassical taste. Indeed, this decorative style, between Baroque and Neoclassicism, is also present on the instrument of Princess Maria Beatrice Barbiano di Belgioioso d’Este (see paragraph above).

These decorative elements are particularly visible on the back of the two instruments, at their bottom, and consist of sinuous plant designs intersected by right angles, drawing geometric shapes reminiscent of the ancient motif of the Greek key.

This array of ornamentation is entirely consistent with the artistic movement of the Age of Enlightenment, in other words the Neoclassicism which emerged in the 1750s and reached its peak around 1780. Evidence of it can be found on various representations of Charles III of Spain, for instance on an engraving by Giovanni Morghen showing the king’s profile on a medallion pendant connected to its chain by shapes also reminiscent of the Greek key.

This Neoclassical style is also noticeable on our mandolin in the large rosette with wide strips of tortoiseshell, divided symmetrically by mother-of-pearl inlays. In addition, the full-length portrait of Charles III produced around 1765 by the foremost neoclassical painter Anton Raphaël Mengs, depicts him in front of his coat of arms framed by a scroll made up of palm leaves, acanthus leaves and shells, motifs from which Vinaccia drew inspiration for the decoration of the mandolin for sale on 5 November 2022 at Vichy Enchères.

Finally, we should mention an interesting engraving by Filippo Morghen kept in the Prado museum and depicting Charles III in front of various symbolic items, including a bearded face with a helmet, which is reminiscent of the two grotesque figures merging into the decoration of the front of our mandolin.

Mainly thanks to the Vinaccias, Naples became the preeminent centre of mandolin making in the 18th and 19th centuries. There were other production centres, but Naples overshadowed them and asserted itself as the undisputed capital of the mandolin, and the instruments of the Vinaccia family acquired and maintained a high reputation internationally.

“[The] instruments built by the Vinaccia family still had the highest international reputation. The core of the family business had occupied the same premises in the rua Catalana since the mid-eighteenth century, until increased demand finally forced most of them to relocate to a larger building in the 1890s”

Paul Sparks, The Classical Mandolin, Oxford University Press, 2005

If Antonio Vinaccia was no boubt one of the main representatives of the dynasty, it is his grandson Pasquale Vinaccia (1806-1882) who took the instrument into the modern era in the 19th century. Indeed, around 1830, he completely redesigned the mandolin by introducing technical innovations. He was particularly interested in machine heads and high-tension steel strings, which subsequently became the standard. He also extended the fingerboard to 17 frets, increasing the range of the instrument. Amongst the first makers to develop the mandolin alongside the Vinaccias in the 18th century, we must mention Luigi Salsedo, also from Naples, a first-class maker whose model “is somewhat smaller than the Vinaccia, and the build is a little heavier, but the workmanship is admirable – the tone and intonation alike are good.”[1]

[1] Richard Harrison, “The mandoline”, in The Bazaar, The Exchange and Mart, 3 janv. 1894, pp.24-25.

Furthermore, alongside the Vinaccias in the 18th and 19th centuries, the most important manufacturers of Neapolitan mandolins included the Calaces, Fabricatores and Filanos. From 1770, the volume of the instrument’s body started to increase, which is particularly noticeable in the production of Giovanni Battista Fabricatore. On 5 November 2022, you will be able to view a beautiful mandolin by this maker, made in 1789, originating from the Calas collection. During the 19th century, the Vinaccias also faced serious competition from the likes of the Calaces.

Both musicians and makers, Raffaele (1863-1934) and his brother Nicola (1859-1923) Calace introduced improvements in construction that modernized the mandolin, in particular by lengthening the fingerboard and therefore increasing the range of the instrument. The Neapolitan style of mandolin making was adopted and developed by makers in other centres, in particular Rome with Giovanni De Santis, Giovanni Battista Maldura and Luigi Embergher. The latter, a particularly innovative maker, produced a cubist mandolin that was totally groundbreaking and which remains the only known example of its kind. A true work of art, this instrument was sold at Vichy Enchères in 2012.

After being fashionable at European courts in the 18th century, the mandolin became more popular in the 19th century, becoming a symbol of the love serenade. However, the patronage of the Queen of Italy Margaret of Savoy contributed to the reevaluation of the instrument and its spread, with the creation of several orchestras playing on the instrument. Once again, the queen called upon the Vinaccias for the commission of her personal instruments… See you on 5 November 2022 for the sale of this exceptional mandolin by Antonio Vinaccia.