Pas moins de cinq archets d’Étienne Pajeot seront vendus à Vichy Enchères le jeudi 2 décembre 2021. Cette importante réunion d’instruments du maître mirecurtien nous donne l’occasion de redécouvrir sa production, l’évolution de son style et ses innovations. Parmi ces modèles, vous trouverez deux archets de violoncelle, un d’alto et deux de violon. Outre leur état remarquable, ces instruments ont de belles provenances – parfois des plus prestigieuses – puisque deux archets appartenaient respectivement au violoncelliste Anner Bylsma (1934-2019) et au violoniste Luben Yordanoff (1926-2011)…

Étienne Pajeot est l’un des plus brillants archetiers de sa génération et l’une des figures majeures de Mirecourt. Alors qu’il aurait pu rejoindre Paris, à la manière d’un grand nombre de luthiers et d’archetiers mirecurtiens dont l’exemple le plus fameux est Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, il n’en fit rien. Au contraire, il resta toute sa vie fidèle à la ville qui le vit naître en 1791. Pourtant, il y mena une vie personnelle difficile, puisque sa mère mourut peu de temps après sa naissance, qu’il perdit son père à l’âge de treize ans et qu’il décéda lui-même précocement en 1849 – âgé seulement de 58 ans.

Son père, Louis Simon Pajeot, était également archetier et tout porte à croire qu’Étienne se forma auprès de lui de ses 10 à 13 ans. Une chose est sûre, son style est très influencé par celui de Louis Simon et cela pendant toute la première partie de sa carrière – nous y reviendrons. Comme un clin d’œil historique, un archet du père, réalisé vers 1790, sera également vendu le 2 décembre 2021 aux côtés des instruments du fils…

Bien que son acte de décès ne fasse mention d’aucune activité professionnelle, Étienne Pajeot fut à la tête d’un atelier florissant qui vit passer d’importantes figures de l’archeterie, dont certainement Nicolas Maire qui développa un style très proche de celui de Pajeot dans sa première époque (voir à ce sujet, notre article sur Nicolas Maire). Les deux hommes travaillèrent probablement ensemble lors de la crise économique de 1830 et fournirent des ateliers parisiens, dont la maison Gand[1].

[1] Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.128

On retrouve notamment chez Maire et Pajeot, la même utilisation du retour à la coulisse et l’usage de la double nacre sur la hausse. Étienne Pajeot étant déjà un luthier accompli dès 1810-1815, on peut penser qu’il a influencé Nicolas Maire et non l’inverse. Le 2 décembre 2021, cinq archets de ce dernier seront mis en vente à Vichy Enchères et offriront un bel aperçu de sa production.

L’atelier de Pajeot fut également fréquenté par Joseph Fonclause, comme en témoigne la proximité stylistique de ses archets avec ceux du maître et particulièrement “son style de tête assez élevée des années 1830-35”[1].

[1] Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.16

Complétant ce beau panorama de l’école de Pajeot, un archet de Fonclause de cette époque sera vendu le 2 décembre 2021 à Vichy Enchères.

Comme il a été précédemment souligné, les cinq archets de la vente du 2 décembre 2021 sont tous caractéristiques du travail d’Étienne Pajeot à différents moments de sa carrière. Au début de son activité et ce jusque dans les années 1820, notre archetier est fortement influencé par le travail de son père et les deux archets de violoncelle de la vente en sont de bons exemples. Réalisés vers 1820, ils présentent un bec large très creusé sur les côtés, leur donnant une forme triangulaire typique de sa première époque.

Les hausses ont un dégorgement petit et court, des lignes peu profondes et un passant également assez court. Leur volume est plein et trapu. Comme le soulignent les experts Sylvain Bigot et Yannick Le Canu, cet aspect très ramassé des hausses s’explique certainement par le “souci de solidité et la volonté d’Étienne Pajeot d’inscrire ses archets dans la durabilité. C’était quelqu’un de très technique et réfléchi”.

En outre, ces archets présentent des viroles fines et étroites, comme on en trouve fréquemment durant sa première époque.

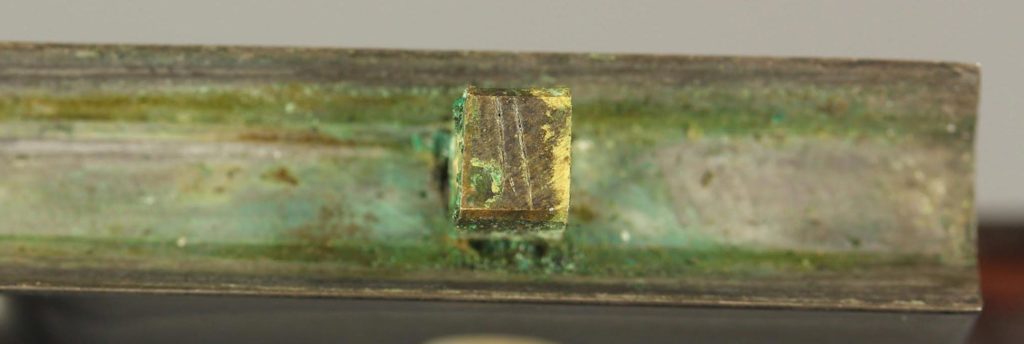

Notons enfin que ces viroles ne sont pas rondes mais martelées en forme d’octogones.

“Ces deux archets s’inscrivent dans la continuité du style du père d’Étienne Pajeot, Louis Simon, et sont caractéristiques de sa première période. L’archetier, toujours à la recherche de l’archet le plus abouti, n’hésite pas à se compliquer le travail en martelant ses viroles et en montant ses boutons octogone/octogone.”

Sylvain Bigot, Yannick Le Canu, experts en archets

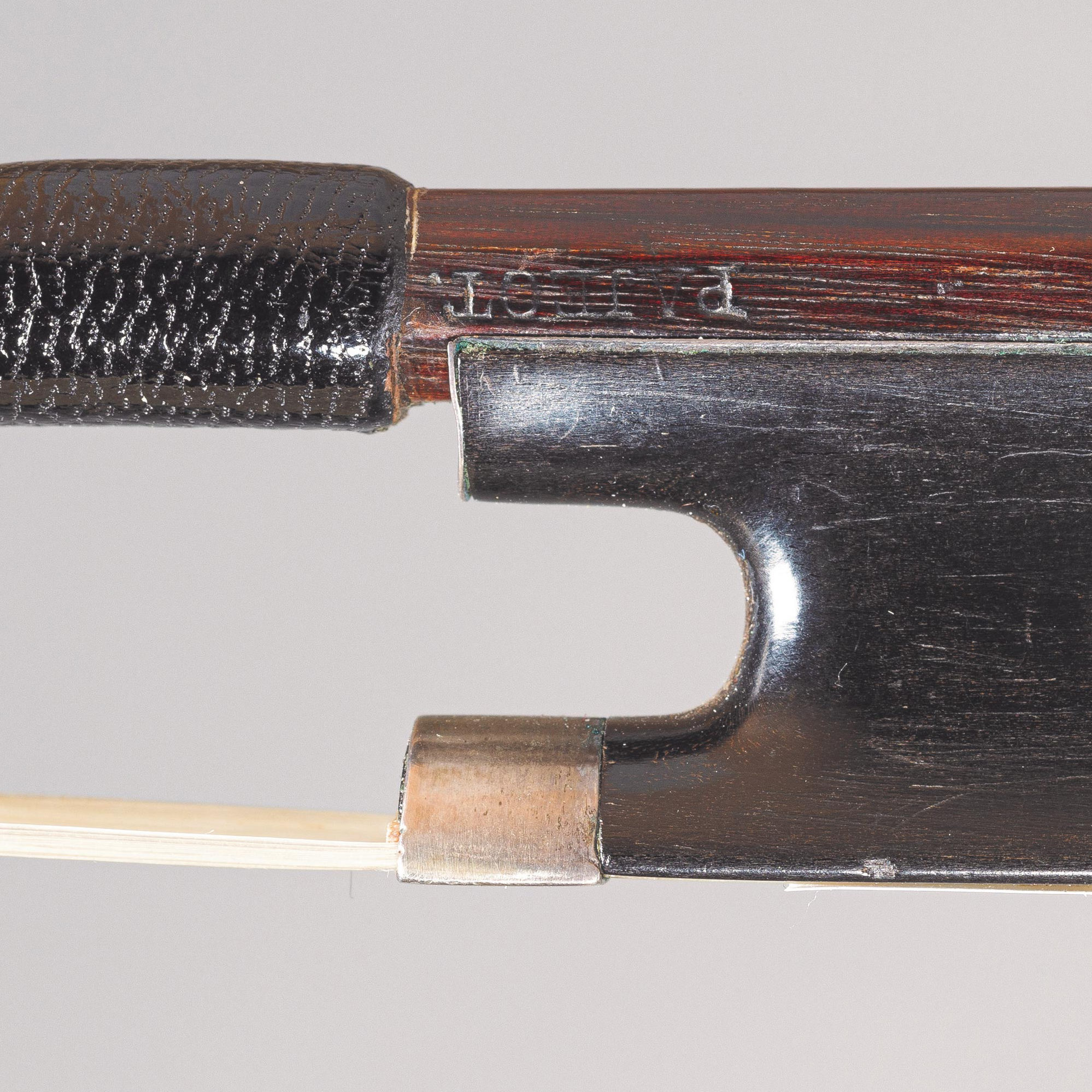

Dans les années 1830, ses archets évoluent et gagnent en raffinement. Très à l’affût des innovations, Étienne Pajeot s’intéresse à la coulisse inventée par François Lupot et au maillechort – ce nouveau métal dont le brevet fut déposé le 22 juin 1827 par Philibert Maillot, manufacturier de couverts de table au 16 quai Saint Antoine à Lyon. Bien que le maillechort ne soit commercialisé qu’au début des années 1830 et que son prix reste élevé, Étienne Pajeot fait partie des premiers à l’utiliser. Le maillechort étant réputé pour sa dureté, il choisit de l’utiliser comme renfort sur les points d’usures et les zones de frottement afin de protéger l’archet et éviter les fractures.

“Il utilise à son tour la coulisse métal, mais en l’adaptant à sa convenance: il place un retour en maillechort sur les hausses montées en argent et en cuivre sur celles montées en or […]. Il soude aussi un retour métallique sur la partie avant de ses boutons argent ou or […], comme l’avait fait précédemment F. Tourte sur ceux montés en or ; il le fait même quelquefois sur la virole arrière.”

Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.15

Prenant en compte les moindres détails, Pajeot est le premier à confectionner des vis en acier bleui pour solidifier le système et éviter la rouille, et ce dès les années 1830.

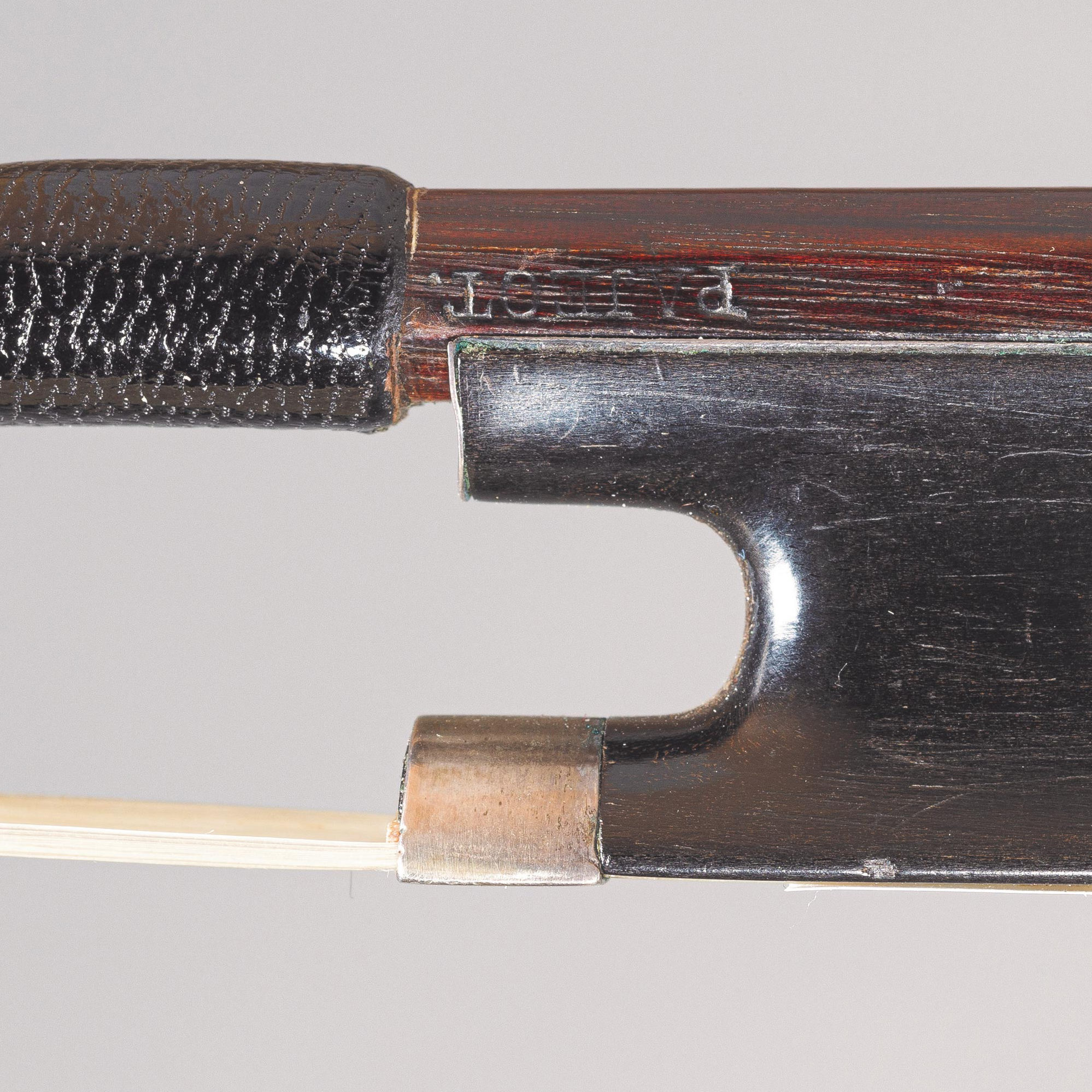

L’archet de violon réalisé vers 1835 et provenant de la collection du célèbre violoniste Luben Yordanoff (1926-2011) est un très bel exemple de modèle de cette époque et est le seul à présenter un retour à la coulisse en argent. En remarquable état, la préciosité de cet instrument l’inscrit déjà dans ce qu’on appellera sa période dorée…

Bien qu’il soit difficile de diviser chronologiquement la production de Pajeot en périodes stylistiques – l’archetier aimant à revenir à ses premiers modèles et à transgresser les règles – on observe un type d’archet plus féminin vers 1835-1845. Rappelons que notre homme meurt en 1849, certainement des suites d’une maladie l’ayant contraint à cesser son activité, ce qui expliquerait que son acte de décès ne mentionne aucune activité professionnelle.

L’archet de violon de la collection Yordanoff, la baguette d’archet de violoncelle ayant appartenue à Anner Byslma, et l’archet d’alto de la vente du 2 décembre 2021, sont caractéristiques de cette période dorée. Les archets ont gagné en élégance, en complexité et en soin.

“Ces trois archets sont très beaux et délicats. On sent qu’Étienne Pajeot est au summum de ses capacités et qu’il s’attache aux moindres détails. Non seulement ils sont en bon état, mais les matériaux utilisés sont de tout premier ordre. La sélection de bois est peu commune et splendide.”

Sylvain Bigot, Yannick Le Canu, experts en archets

En effet, durant cette période, Pajeot soigne particulièrement la qualité de ses matériaux et spécialement de son pernambouc qui s’avère souvent exceptionnel, d’une couleur rouge orangé à rouge foncé. Cette exigence qualitative contribue à anoblir l’archet et ne se limite pas aux essences de bois, mais concerne également le choix de l’ivoire, de la nacre ou encore de l’écaille.

De manière générale, on observe également que les viroles sont plus grandes, réduisant ainsi la place de l’ébène sur le bouton.

“Etienne Pajeot, on le voit, excelle dans l’innovation, comme dans la décoration de bon goût.”

Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.16

En choisissant de rester à Mirecourt, Étienne Pajeot aurait pu passer à côté d’innovations majeures. Au lieu de cela, il se tint informé des découvertes parisiennes et en fit lui-même de remarquables. Ses échanges commerciaux avec Charles François Gand expliquent certainement en partie sa connaissance des avancées techniques de ses contemporains parisiens. Par ailleurs, il participe à une exposition parisienne en 1819. Son travail n’est pas isolé, mais rencontre une renommée en France et à l’étranger. Outre avec Gand, il a probablement collaboré avec Nicolas Vuillaume pour qui il réalise des archets signés “Stentor” (A ce propos, retrouvez plusieurs instruments de Nicolas Vuillaume lors de notre vente du 2 décembre 2021). Malgré sa situation à Mirecourt, notre archetier était donc très intégré au réseau de l’époque et jouissait d’une solide réputation, garantie par la grande qualité de ses archets et les innovations qu’il mit en œuvre.

“Toutes ces innovations font évoluer considérablement la génération d’archetiers de cette époque ; ceux de Mirecourt, mais également certains Parisiens qui ne manquent pas de les adopter à leur tour”

Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.16

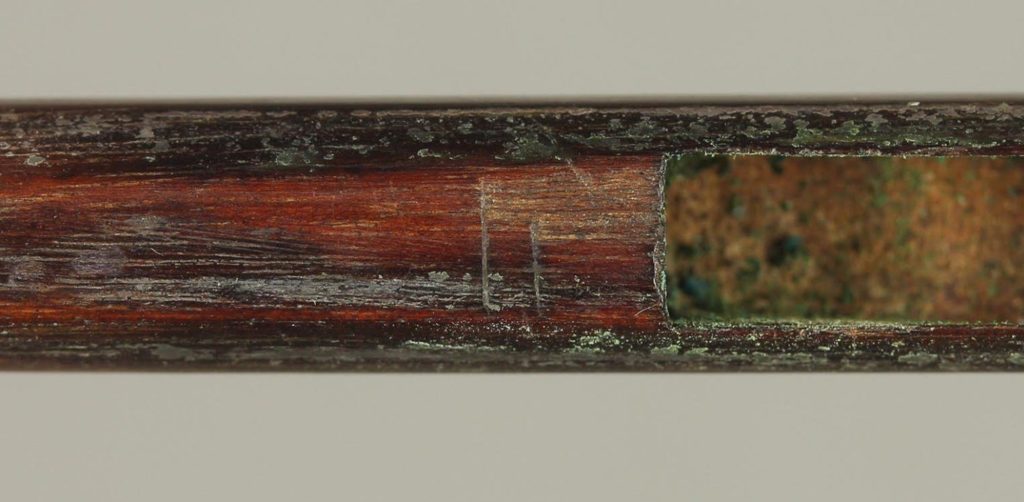

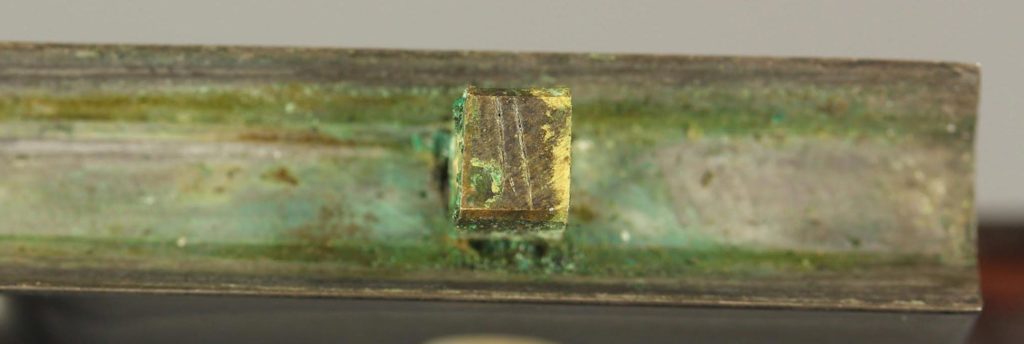

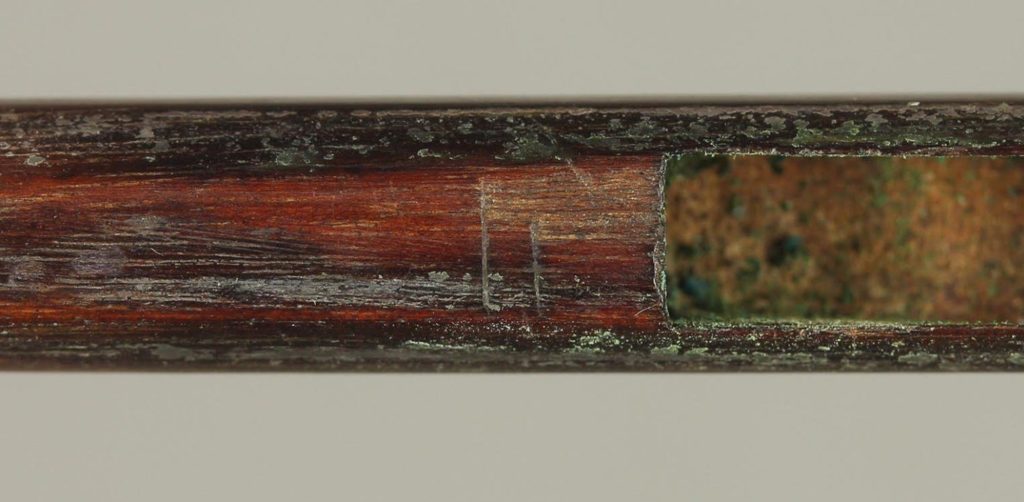

Archetier ingénieux, Étienne Pajeot inventa un système de numérotage que l’on ne retrouve nulle part ailleurs. Il apposa des numéros sur les différentes parties des archets, permettant de les monter sans risquer de les mélanger. En règle générale, les numéros sont en chiffres romains et se trouvent sur l’écrou, la gorge et sur la baguette au niveau de la mortaise. On ne connaît pas d’autres auteurs ayant utilisé ce type de numérotage. Cependant, ce système n’est pas systématique puisque Pajeot ne semble avoir procédé ainsi que sur une courte période.

De plus, peu d’instruments portent les trois numéros. À ce titre, l’archet d’alto n°200 de la vente de Vichy Enchères du 2 décembre 2021 est très intéressant, puisqu’il fait partie des rares modèles numérotés sur les trois parties. En effet, on retrouve bien le numéro “II” sur la baguette, l’écrou et la gorge. Outre le fait d’être caractéristique de la période dorée de Pajeot, cet archet est donc un rare témoignage de son habile système de numérotage.

Insatiable inventeur, Étienne Pajeot mit au point dans les années 1830 l’archet à mèches interchangeables. Bien que cette invention soit associée à Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, il est presque certain qu’Étienne Pajeot et son atelier en soient à l’origine.

On sait notamment qu’il réalise, dès 1834, plusieurs modèles de hausses à mèches interchangeables. En 2015, Vichy Enchères vendait précisément un archet de Pajeot en modèle expérimental à mèches interchangeables.

En outre, on retrouve ce type d’archets dans la production de Nicolas Maire[1] ou Claude Joseph Fonclause – tous deux réputés avoir été élèves de Pajeot. Néanmoins, c’est Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume qui, le 30 novembre 1835, dépose le brevet d’invention de l’archet à mèches interchangeables qu’il produira pendant 15 ans.

“L’intérêt de ce système profite aux musiciens qui n’ont pas l’opportunité de se rendre fréquemment dans les grandes villes. Ils peuvent ainsi remécher eux-mêmes leur archet.”

Voir notre article sur les archets à mèches interchangeables

“Etienne Pajeot demeure l’un des artisans les plus géniaux de sa génération. Il nous laisse une grande quantité d’archets de remarquable qualité, que les musiciens apprécient pour leur jeu et que les collectionneurs affectionnent tout particulièrement pour leur esthétique.”

Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.16

Les instruments de Pajeot sont très prisés pour leurs qualités sonores, ainsi que pour leurs caractéristiques esthétiques. Ils se distinguent notamment par leurs plaques de têtes très marquées et souvent différentes les unes des autres. En début de carrière, les pointes de têtes dessinent des courbes continues tendant vers l’infini, avec une alternance progressive du pernambouc, de l’ébène et de l’ivoire.

En deuxième partie de carrière, on trouve des plaques de têtes présentant des ruptures nettes entre les différents matériaux. Toutefois, rien n’est jamais définitif chez Pajeot puisqu’on le voit jongler entre ces différents types durant toute sa vie.

La comparaison de l’archet d’alto, à la tête rythmée par une succession d’angles, avec celui de la collection Yordanoff, au dessin beaucoup plus doux, est très significative.

Au cours des dernières années, un grand nombre d’instruments de Pajeot vendus à Vichy Enchères sont venus attester du style très affirmé et prononcé propre à l’archetier (voir les quelques exemples suivants).

Enfin, ses archets ont la particularité d’être quasiment tous conçus sous le mode du talon en une seule pièce et présentent, de manière quasiment systématique, un dégorgement court que l’on retrouve davantage en première époque mais qui perdure durant toute sa carrière.

Présentant chacun de multiples intérêts, la réunion de ces cinq archets nous offre un superbe témoignage de la carrière de celui qui fut sans conteste l’un des plus ingénieux maîtres de Mirecourt. Rendez-vous à Paris chez nos experts pour découvrir ces archets, puis à Vichy lors de nos expositions du 28 novembre au 2 décembre 2021. La vente de ces instruments se déroulera le 2 décembre !

No fewer than five Etienne Pajeot bows will for sale at Vichy Enchères on Thursday 2 December 2021. This important collection of bows by the master from Mirecourt gives us an opportunity to re-examine his output, the evolution of his style and his innovations. The items for sale include two cello, one viola and two violin bows. In addition to being in remarkable condition, these bows have notable – sometimes very prestigious – provenance, with two of them having belonged to the cellist Anner Bylsma (1934-2019) and the violinist Luben Yordanoff (1926-2011).

Étienne Pajeot is one of the most accomplished bow makers of his generation and one of Mirecourt’s major figures. While he could have gone to Paris, as did a large number of violin and bow makers from Mirecourt, the most famous being Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, he did not. Instead, he remained faithful all his life to the city where he was born in 1791. He faced many difficulties in his personal life: his mother died shortly after his birth, he lost his father at the age of 13, and he himself died early in 1849 – aged only 58.

His father, Louis Simon Pajeot, was also a bow maker, and everything points to Etienne having trained with him when he was between 10 and 13 years old. One thing is certain: his style was very influenced by that of Louis Simon during the whole of the first part of his career – we will come back to that. In a nod to history, a bow by his father, made around 1790, will also for sale on 2 December 2021, alongside the son’s bows.

Although his death certificate makes no mention of any professional activity, Étienne Pajeot was at the helm of a thriving workshop which employed important names in bow making, most likely including Nicolas Maire, who developed a style very close to that of Pajeot in his early period (on this topic see our article on Nicolas Maire). The two men probably worked together during the economic crisis of 1830 and supplied Parisian workshops, including Maison Gand[1].

[1] Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.128

In particular, Maire and Pajeot both used of the same type of metal plate on the bottom slide, as well as double mother-of-pearl on the frog. Étienne Pajeot was already an accomplished bow maker by 1810-1815, and therefore it is likely he is the one who influenced Nicolas Maire, not the other way around. On 2 December 2021, five bows by the latter will be for sale at Vichy Enchères, providing a good overview of his production.

The Pajeot workshop was also visited by Joseph Fonclause, as evidenced by the stylistic similarity between his bows and those of the master, in particular “his rather high style of heads in the period 1830-35”[1].

[1] Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.16

Completing the impressive array of Pajeot school bows for sale on 2 December 2021 at Vichy Enchères, a Fonclause bow from this period will also be included.

As previously noted, the five bows in the sale on 2 December 2021 are each typical of the period of Etienne Pajeot’s career in which they were made. From the start of his activity until the 1820s, he was heavily influenced by his father’s work, and the two cello bows on sale are good examples of that. Made around 1820, they feature large tips, deeply carved out on the sides, giving them a triangular shape typical of his early period.

The frogs have small and shallow throats, not very hollowed out, and the ferrule is also rather short. Their appearance is full and stocky. As experts Sylvain Bigot and Yannick Le Canu point out, this very compact appearance of the frogs probably stems from “Etienne Pajeot’s focus on strength and ensuring his bows would stand the test of time. He was a very technical and thoughtful individual.”

In addition, these bows have fine and narrow buttons, as often found in his first period.

Finally, it is worth noting that these ferrules are octagonal, not round.

“These two bows are a continuation of the style of Etienne Pajeot’s father, Louis Simon, and are typical of his first period. The bow maker, in his constant quest for the most successful bow, did not shy away from making extra work for himself by hammering his button rings and mounting them on an octagon / octagon pattern.”

Sylvain Bigot, Yannick Le Canu, experts en archets

In the 1830s, his bows evolved and gained in refinement. Always on the lookout for innovations, Étienne Pajeot took an interest in the bottom slide invented by François Lupot, which was made of nickel silver – a new metal whose patent was filed on 22 June 1827 by Philibert Maillot, manufacturer of tableware, 16 quai Saint Antoine in Lyon.

Although nickel silver was not commercially available until the early 1830s and its price remained high, Étienne Pajeot was among the first to use it. As nickel silver is renowned for its hardness, he chose to use it as reinforcement in areas of heavy wear and rubbing in order to protect the bow and prevent cracks.

“He also used the metal slide, but made adjustments to it: he fitted nickel silver plates on his silver mounted frogs and copper ones on his gold mounted ones […]. He also weld a metallic reinforcement on the front of his silver or gold buttons […], as F. Tourte had done previously on his gold mounted bows; he even sometimes did it on the rear button ring.”

Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.15

Pajeot gave great consideration to every detail, and, from the 1830s, was the first to make screws from blued steel to strengthen the mechanism and protect it from rust.

The violin bow made around 1835 and from the collection of the famous violinist Luben Yordanoff (1926-2011) is a very fine example from this period and the only one to feature a silver plate on the bottom slide. It is in remarkable condition, and the quality of its craftsmanship signals the start of what would later be referred to as the maker’s golden period.

Although it is difficult to divide Pajeot’s production chronologically into stylistic periods – the bow maker being fond of reverting to early models or deviating from the rules of a particular period – a more ‘feminine’ type of bow emerged around 1835-1845. It’s worth remembering that Pajeot died in 1849, probably as a result of an illness that forced him to cease his professional activity, which would explain why his death certificate does not mention any. The violin bow from the Yordanoff collection, the cello bow stick that belonged to Anner Byslma, and the viola bow from the 2 December 2021 sale are all typical of this golden period. The bows gained in elegance, complexity and quality of execution.

“These three bows are very beautiful and delicate. You can feel that Étienne Pajeot was at the peak of his abilities and that he paid attention to the smallest details. Not only are they in good condition, but the materials used are of the highest calibre. The wood used is unusual and of superb quality.”

Sylvain Bigot, Yannick Le Canu, experts en archets

Indeed, during this period, Pajeot paid particular attention to the quality of his materials and especially his pernambuco, which is often exceptional, ranging from orange-red to dark red in colour. His high standards in selecting wood, but also ivory, tortoiseshell and mother-of-pearl contributed to elevating his bows.

In addition, we note that the button rings became larger, thus reducing the width of the ebony on the button.

“Etienne Pajeot, as we can see, excelled as an innovator, as well as in the tasteful ornamentation of his bows.”

Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.16

By choosing to stay in Mirecourt, Étienne Pajeot could have missed out on major innovations. Instead, he kept abreast of discoveries made in Paris and made some remarkable ones himself. His trade relations with Charles François Gand certainly explain in part his knowledge of the technical advances of his Parisian contemporaries. He also took part in an exhibition in Paris in 1819. His work was not carried out in isolation, and found success in France and abroad. Besides Gand, he probably collaborated with Nicolas Vuillaume, for whom he made bows stamped “Stentor” (in relation to this, please note that you can find several instruments by Nicolas Vuillaume in our sale on 2 December 2021). Despite being based in Mirecourt, Pajeot was therefore well connected in the violin making circles of the time and enjoyed a solid reputation, stemming from the high quality of his bows and the innovations he implemented. en œuvre.

“All of these innovations contributed significantly to the evolution of bow making at that time, and had a profound influence on his contemporaries, whether in Mirecourt or Paris, who were quick to incorporate his innovations into their work.”

Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.16

Étienne Pajeot was an ingenious bow maker who invented a unique numbering system. He placed numbers on the different parts of the bows, to mitigate the risk of assembling non matching parts. Usually, the numbers are in Roman numerals and are found on the eyelet (frog), collar (button and screw), and eyelet and screw mortice (stick). No other maker is known to have used this type of system. However, it was not used consistently, and was only in place for a short period of time it seems.

Moreover, few bows carry all three numbers. Therefore, the viola bow, lot no. 200 in the Vichy Enchères sale on 2 December 2021, is very interesting, since it is one of the few numbered examples to carry the number on all three parts. The number “II” can indeed be found on the stick, eyelet and collar. Besides being typical of Pajeot’s golden period, this bow is therefore a rare testimony into his clever numbering system.

Étienne Pajeot continually innovated, and one of his innovations in the 1830s was a bow with interchangeable hair. Although this invention is associated with Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume, it is almost certain that it originated from the workshop of Etienne Pajeot.

In particular, we know for a fact that he produced, from 1834, several examples with interchangeable hair. In 2015, Vichy Enchères sold one such Pajeot bow, an experimental example with interchangeable hair.

In addition, we find this type of bow in the production of Nicolas Maire[1] and Claude Joseph Fonclause – both makers thought to have been pupils of Pajeot. Nevertheless, it was Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume who, on 30 November 1835, filed the patent for this invention, which he produced for 15 years.

“This system is particularly useful to musicians who do not have the opportunity to travel frequently to large cities. It allows them to re-hair their bow themselves”

See our article on bows with interchangeable hair

“Etienne Pajeot remains one of the most brilliant craftsmen of his generation. He left us a large quantity of bows of remarkable quality, which musicians appreciate for their playing and which collectors particularly prize for their aesthetics.”

Bernard Millant, Jean-François Raffin, L’Archet, Paris, L’Archet Editions, 2000, tome II, p.16

Pajeot’s bows are highly prized for their acoustic qualities, as well as for their aesthetics. They are distinguishable in particular by their very bold head facings, which are often different from each other. In his first period, the head tips draw continuous curves tending to infinity, with a gradual alternation of pernambuco, ebony and ivory.

In his second period, we find head facings with a clear delineation between the different materials. However, nothing is ever definitive with Pajeot, and he alternated between these different types of head facings throughout his life.

The comparison of the viola bow, with its head shaped by a succession of angles, with the bow from the Yordanoff collection, whose head has a much softer design, is very instructive.

In recent years, the large number of Pajeot bows sold at Vichy Enchères has provided evidence of the very assertive and individual style of this bow maker (see the few examples below).

Finally, his bows have the particularity of being almost always designed with a one-piece heel, and almost invariably have a shallow throat, a feature that is more common in his first period, but persisted throughout his career.

Each worthy in their own right, the coming together of these five bows offers us a superb testimony into the career of, undoubtedly, one of the most ingenious masters of Mirecourt. Visit our experts in Paris to discover these bows, then in Vichy during our exhibitions from November 28 to December 2, 2021. The sale of these instruments will take place on December 2nd !