Quel est le plus vieux piano réalisé en France ? C’est à cette question que la découverte d’un instrument inédit de Jean-Kilien Mercken (1743-1819) nous invite à réfléchir. Inconnu jusque-là, ce “pianoforte en forme de clavecin” – ainsi qu’on appelait les pianos à queue avant le XIXème siècle – remet en perspective l’histoire de la facture française de pianos et vient éclairer un autre pan de la production de Mercken, uniquement connu pour ses pianofortes carrés. Vichy Enchères vous propose de lever le voile sur ce modèle énigmatique – probablement le premier piano à queue français -, à la lumière de l’histoire de l’émergence de l’instrument au XVIIIème siècle.

De la famille des instruments à cordes et à clavier, le piano est en quelque sorte la mécanisation du tympanon, instrument à cordes frappées, ce qui lui permet une expression dynamique, impossible avec des cordes pincées. Son cousin le clavicorde, dont les cordes sont excitées à leur extrémité par des lames métalliques appelées “tangentes”, possède déjà des possibilités dynamiques mais son faible volume sonore ne lui permet pas la concurrence d’autres instruments. C’est autour de 1700, à Florence, que l’instrument naquit dans l’atelier de Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655-1731). Alors au service du prince Ferdinand de Médicis, Cristofori inventa le mécanisme du pianoforte dont allait hériter le piano moderne. Ce mécanisme repose sur des cordes frappées par des marteaux recouverts de peau reliés à la touche, et sur un système d’échappement permettant au marteau de retomber loin après avoir frappé les cordes, plutôt que de rester près.

Ces nouveautés furent décisives puisqu’elles permirent de passer graduellement de la nuance piano à forte, d’où l’appellation pianoforte. Dans une inventaire de 1700, les premiers pianofortes de Cristofori sont qualifiés par le terme “arpicembalo” (ou “harpe-clavecin”) car ces derniers sonnaient comme la harpe. En 1711, Scipione Maffei publia un article dans le Giornale de’ letterati d’Italia décrivant un “Gravicembalo [grand clavecin] col piano, e forte” et diffusant le dessin de sa mécanique. Cristofori le perfectionna dans les années 1720 et ce modèle rencontra un certain succès en Italie et également au Portugal et en Espagne, où il fut introduit par Domenico Scarlatti et Carlo Brosi, dit Farinelli.

C’est en Saxe que s’opéra réellement la diffusion et le développement du nouvel instrument. En 1705, Pantaleon Hebenstreit (1668-1750) fabriqua un tympanon géant qu’il présenta à la cour de Louis XIV. Les auditeurs furent éblouis par la variété des sons produits avec les marteaux soit en bois dur, soit garnis de laine, et surtout par l’effet de résonance des cordes non étouffées. Le roi, non moins charmé, décida de nommer l’instrument “Pantalon” en l’honneur de son inventeur. Simultanément, l’allemand Christopher Schröter construisit en 1717 deux modèles inachevés de pianos à mécanique à marteaux et en présenta à la cour de Saxe en 1721. L’ancêtre du piano moderne fut réellement diffusé par des facteurs d’orgues allemands (qui construisaient également clavecins et clavicordes), dont le plus célèbre est Gottfried Silbermann (1683-1753). C’est à lui que s’adressa Hebenstreit pour la fabrication exclusive de ses “Pantalons” et parallèlement, Silbermann eut l’idée de construire quelques pianofortes en forme de clavecin, probablement munis de mécaniques basées sur le dessin de Cristofori – publié en Allemagne en 1725.

Johann Sebastien Bach les essaya mais les jugea trop lourds et lents, ce qui encouragea Silbermann à changer la mécanique et à introduire des manettes pour lever les étouffoirs, afin de produire un effet proche de celui tant apprécié du “pantalon”. Ce modèle reçut l’approbation de Bach et fut offert en 1746 en quatre exemplaires au roi Frederick, à Potsdam. Gottfried Silbermann sera longtemps considéré comme l’inventeur du piano-forte et plus tard, son neveu Johann Heinrich Silbermann, installé aux côtés de son frère Johann Andreas à Strasbourg, reprendra l’essentiel de ce modèle. En parallèle des travaux des Silbermann, axés sur le piano en forme de clavecin dans la tradition de Cristofori, d’autres facteurs d’orgues s’inspirèrent des timbres du “pantalon” et fabriquèrent des instruments émettant un “arc-en-ciel sonore” à l’aide de marteaux en bois dur ou garnis de peau. Jugeant la mécanique à échappement trop lourde et trop lente, ils firent des mécaniques sans échappement, certes moins riches en nuances, mais extrêmement rapides. Vers 1758, un élève de Gottfried Silbermann, Christian Ernst Friederici (1709-1780) eut l’idée de combiner les possibilités du pantalon avec la forme du clavicorde et nomma cet instrument le “Fortbien”.

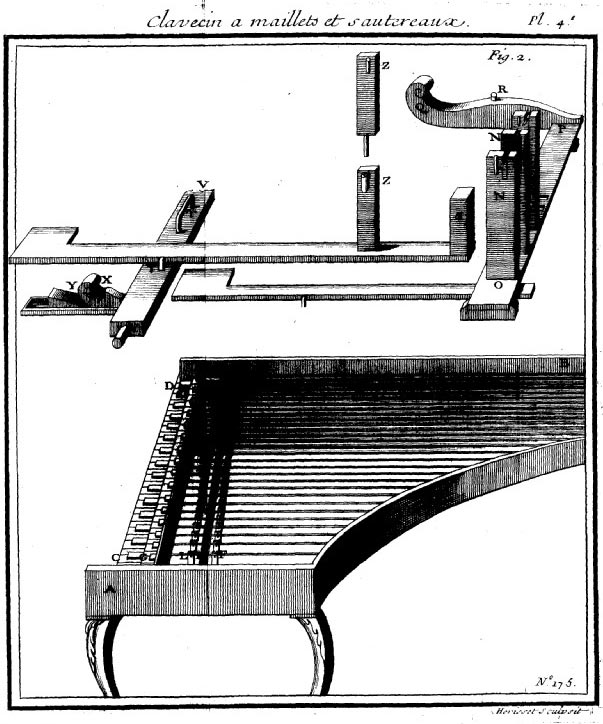

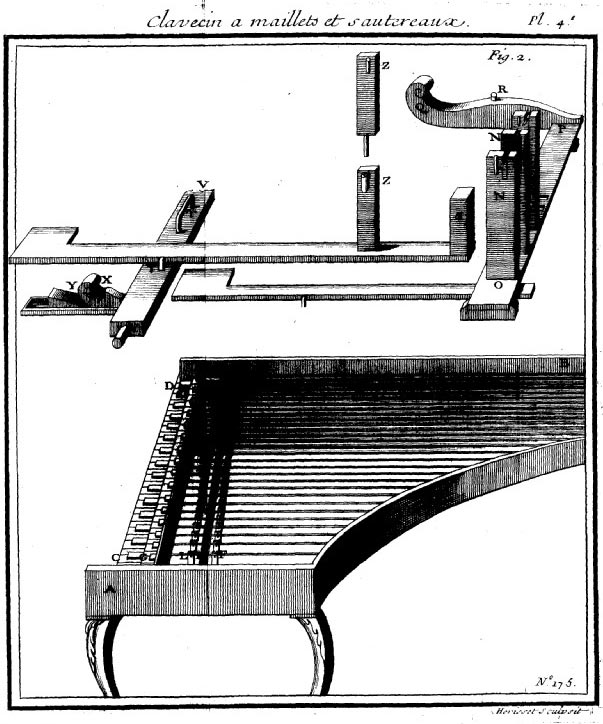

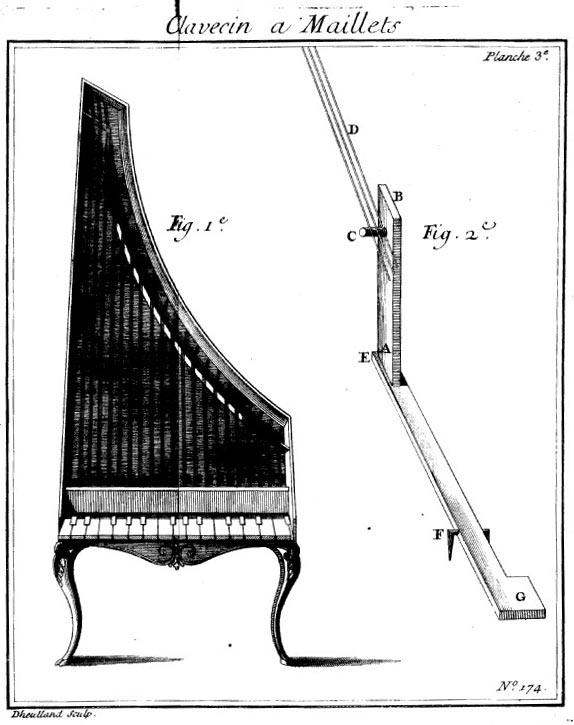

Contrairement aux facteurs allemands, rompus aux claviers expressifs et aux timbres variés, les facteurs français furent moins polyvalents et innovants et restèrent très attachés à la production de clavecins et épinettes durant les trois premiers tiers du XVIIIème siècle. Le clavicorde demeura inconnu en France. Notons toutefois qu’en 1716, le facteur Jean Marius présenta à l’Académie des Sciences de Paris quatre instruments au mécanisme substituant les marteaux aux sautereaux, qu’il appella “clavecins à maillets” – mais qu’il ne fit pas construire faute d’appartenir à la Communauté des Maîtres Faiseurs d’Instruments de Musique. Ainsi, en France, lorsque l’on souhaitait se procurer un pianoforte, on faisait appel aux facteurs allemands et alsaciens pour les modèles en forme de clavecin, et à partir de 1765, aux Anglais pour ceux carrés. A contrario, les facteurs de pianofortes produisant en France, à l’image de Mercken, étaient particulièrement rares. De ce fait, le plus vieux piano à queue conservé en France, au Musée de la musique, n’a pas été réalisé en France mais provient de Suisse où il a été fabriqué en 1763 par Johann Ludwig Hellen.

Comme l’indiquent Marie-Christine et Jean-François Weber dans l’ouvrage de référence sur Mercken, le premier pianoforte connu construit à Paris est un modèle carré de Mercken daté de 1770 et conservé au Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers de Paris. Léon Pillaut écrivait dès 1889 dans le catalogue de l’Exposition universelle :

Le plus vieux piano est un français de Mercken (Paris 1770) ; il est d’une facture très soignée et très élégante.

La découverte de ce pianoforte en forme de clavecin vient remettre les choses en perspective, puisque ce nouvel instrument a très certainement été réalisé avant celui des Arts et Métiers, vers 1767-68. Il serait donc le plus ancien piano à queue français parvenu jusqu’à nous. C’est également le seul instrument connu de Mercken qui épouse cette forme de clavecin. Mis à part ce piano à queue, peu d’autres modèles français de cette époque nous sont connus. Pascal Taskin en réalisa plusieurs qu’il présenta à l’Académie des Sciences, mais seulement entre 1776 et 1791.

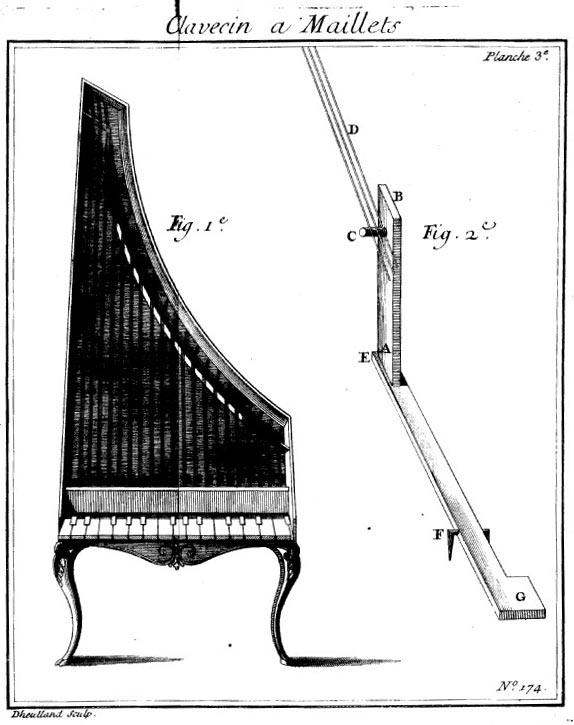

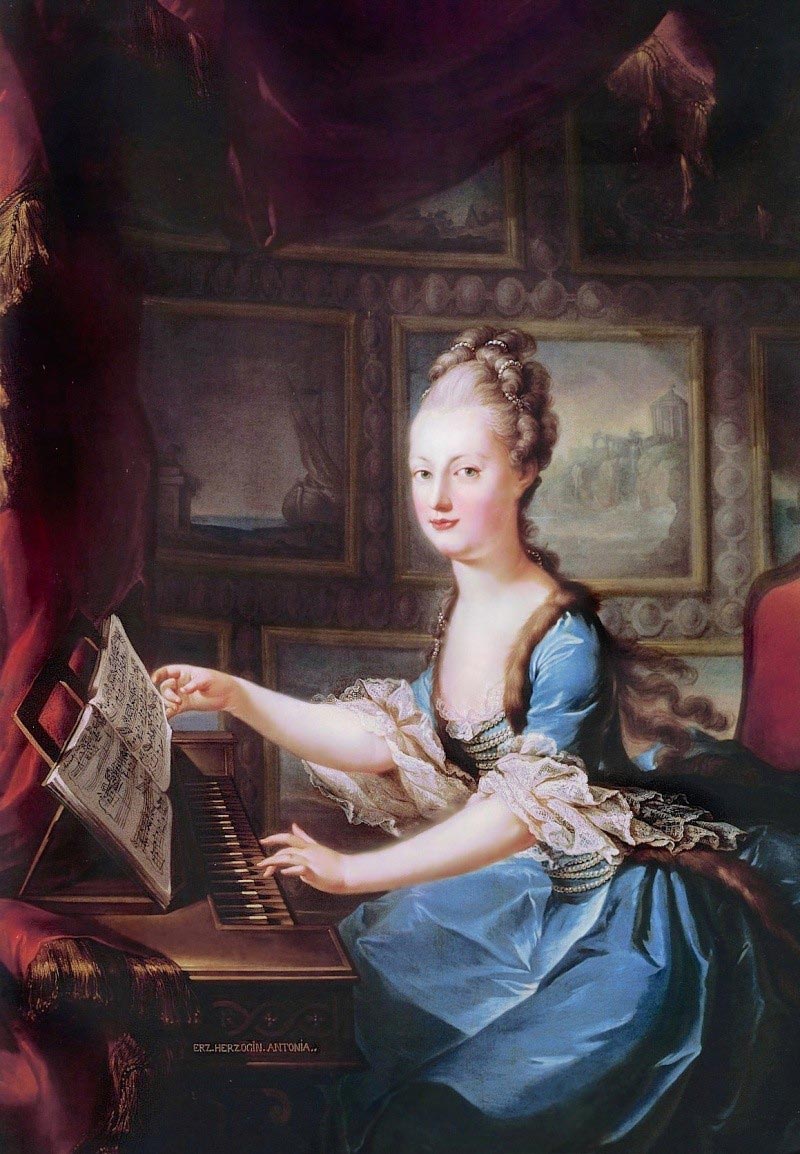

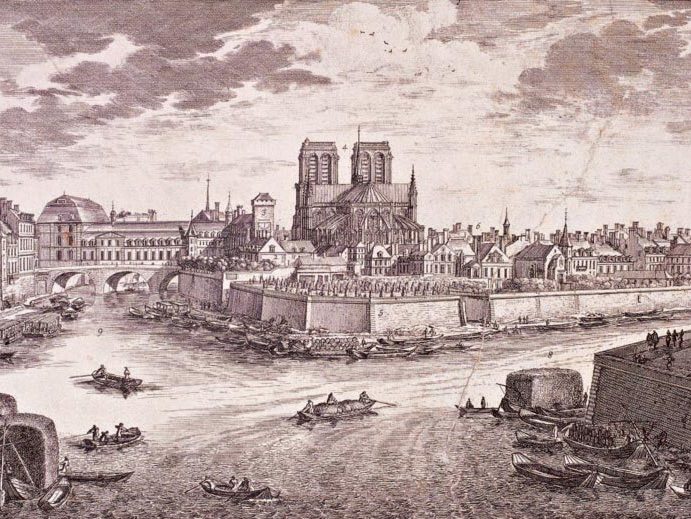

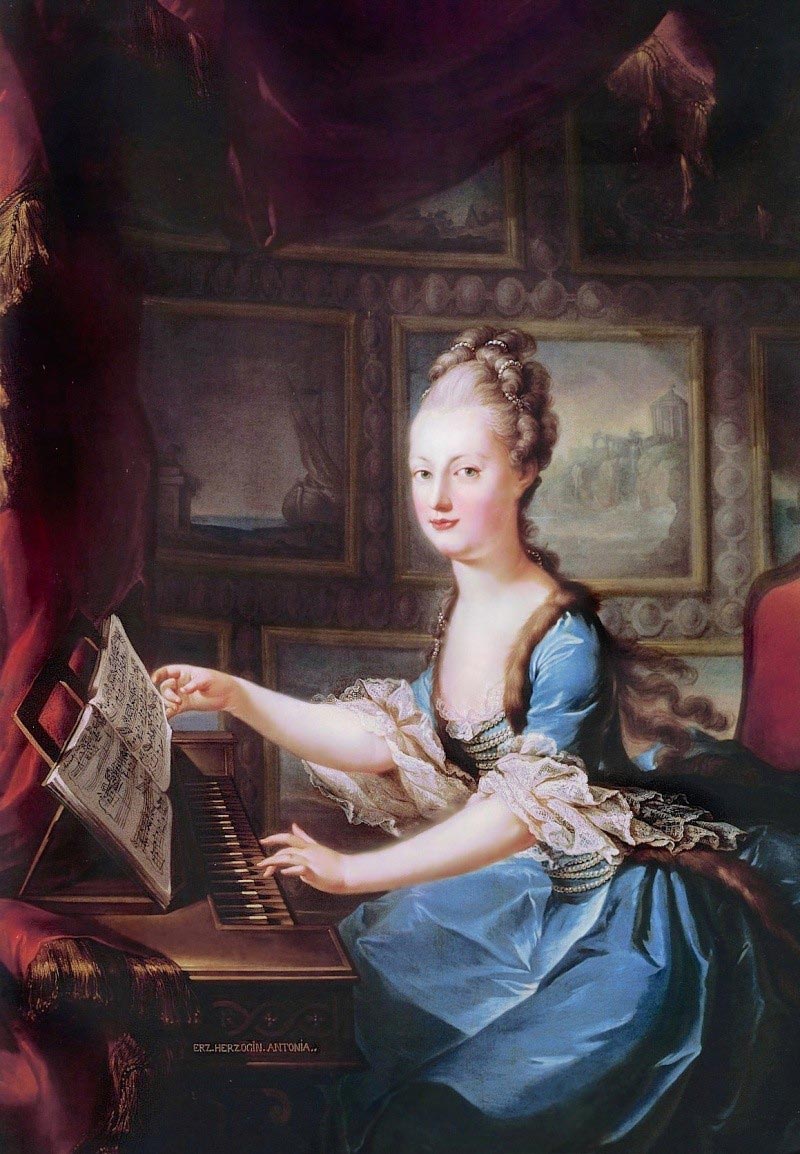

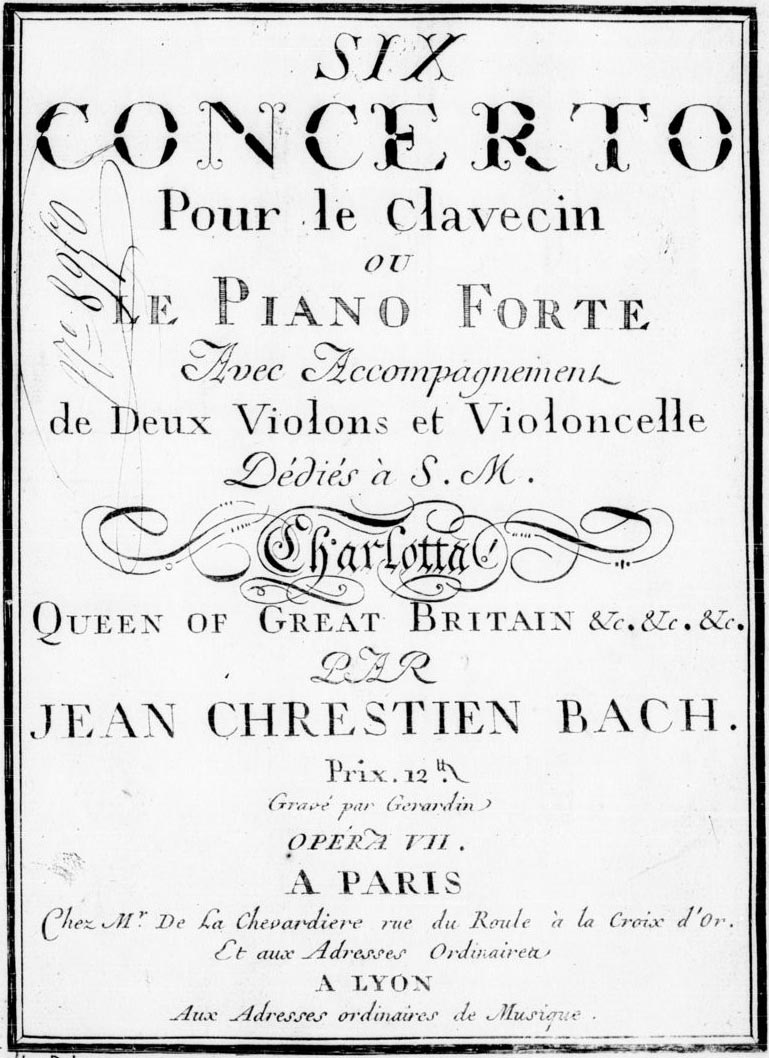

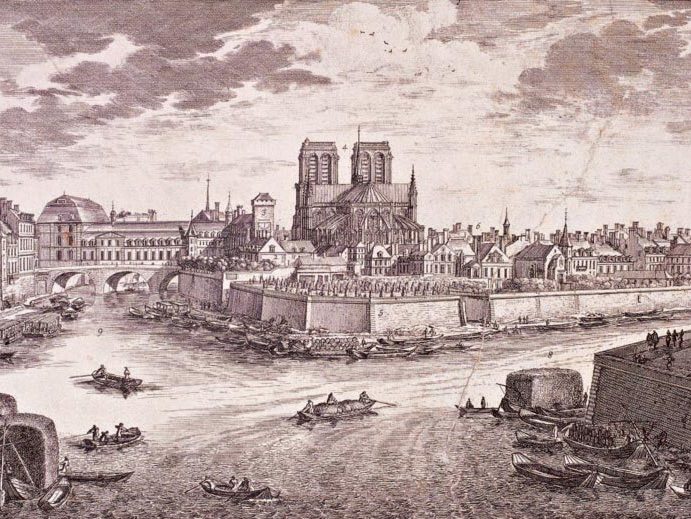

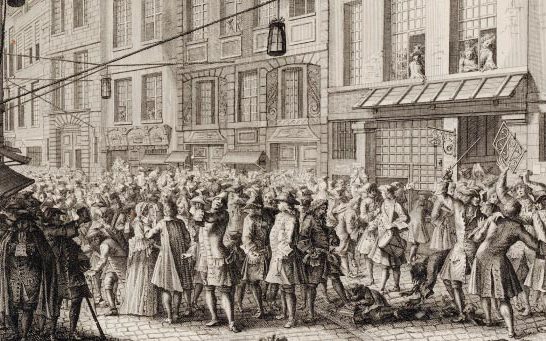

Si aux XVIIème et XVIIIème siècles, le clavecin est en vogue dans la musique et les cours européennes, le pianoforte lui prit la vedette à partir du dernier tiers du XVIIIème siècle. Néanmoins, c’est bien au clavecin que Marie Antoinette se fait portraiturer en 1769 par Franz Xaver Wagenschön, et l’instrument est encore présent dans la Conversation musicale de Trinquesse datée de 1774. Il faut dire qu’avant les années 1770, le pianoforte restait assez rare sur le sol français. Toutefois, vers 1765, l’allemand Johannes Zumpe commença à fabriquer des petits pianos carrés à Londres, inspirés par le “Fortbien” de Friederici et dotés d’une mécanique simplifiée sans échappement avec des marteaux garnis de peau. Ces instruments sont les premiers pianos conçus pour être produits en série. Les musiciens et amateurs, aristocrates et bourgeois anglais, suivis de peu par les Français, furent presque instantanément séduits par leur charmante sonorité, leur prix trois fois moins élevé que le clavecin, leur élégance et leur petite taille. Le premier concert public à Paris fut donné en 1768, au Concert Spirituel[1] et Jean-Chrétien Bach composa aussitôt des concertos pour clavecin ou pianoforte. Madame Brillon de Jouy, grande virtuose du clavier, fut l’une des premières clientes. Ainsi, dès les années 1770, les annonces de pianofortes se firent plus fréquentes dans les journaux français et les rapports entre le clavecin et le piano s’inversèrent, conduisant à l’abandon progressif du clavecin à la fin du siècle.

Le phénomène du pianoforte carré fut en partie sociétal, puisque l’instrument devint un symbole distinctif de bon goût et de haute position dans la société, dont usa notamment la bourgeoisie pour atteindre ses prétentions.

Une sorte de galerie de femmes du monde posant au pianoforte se développe ainsi avant la Révolution, montrant combien l’instrument est l’indispensable accessoire de la modernité et d’une mode féminine qui s’inscrit dans la descendance des portraits au clavecin que nous avions observés entre 1690 et 1770. Remarquons que le modèle dominant d’instrument est sans conteste le piano carré.

Florence Gétreau. Les images de pianistes en France, 1780-1820. Musique, images, instruments, Paris: Ed. Klincksieck; Paris: Laboratoire d’organologie et d’iconographie musicale CNRS, 2009, Le pianoforte en France 1780-1820, 11, pp.136-149.

[1] Marie-Adélaïde de Place. Le piano-forte en France de 1760 à 1812. In: École pratique des hautes études. 4e section, Sciences historiques et philologiques. Annuaire 1976-1977, p.1117.

Mercken semble être le premier facteur parisien à avoir copié les pianos carrés anglais, pariant avec clairvoyance sur un marché en pleine expansion. L’ouvrage de référence des Weber sur le facteur ne mentionne ainsi que des pianos carrés, dont un beau modèle de 1781, signé “Johannes Kilianus Mercken Parisiis fecit 1781 / Rue du Chantre, près le Louvre”, que Vichy Enchères aura également l’honneur de présenter à la vente le 7 mai 2022, à côté du piano à queue.” Avant la découverte du modèle de la vente Vichy Enchères de mai 2022, on ne lui connaissait en effet aucun pianoforte en forme de clavecin. Il faudra attendre les années 1790 et Erard pour que le piano à queue prenne son essor – Haydn et Beethoven feront partie de ses premiers partisans. Si Erard choisit d’adopter ce type de pianos, ce fut principalement pour permettre à l’instrument d’intégrer l’orchestre en lui donnant plus de puissance.

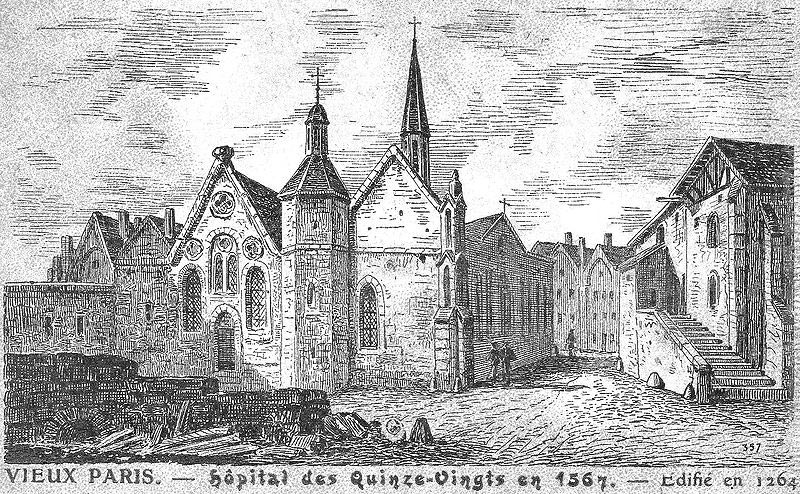

Jean-Kilien Mercken (1743-1819), dit aussi Johann Kilian Mercken ou Johannes Kilianus Mercken, est né à Übach, au nord d’Aix-la-Chapelle, alors possession de l’Autriche. Comme beaucoup de facteurs d’instruments allemands, Mercken émigre en France. On le retrouve à Paris vers 1767, à l’âge de 25 ans[1]. Ses origines et son parcours ne lui permettent pas d’exercer librement son métier, régi par la Communauté des faiseurs d’instruments de Musique. D’abord installé dans l’enclos protégé de l’Hôpital Royal des Quinze-Vingts comme facteur de clavecin – tout comme Joseph Raoux – , il déménage vers 1780 rue du Chantre, comme nous pouvons le lire sur l’inscription du pianoforte carré de 1785 conservé au Musée de la Musique.

[1] Marie-Christine et Jean-François Weber, J.K. Mercken, Premier facteur parisien de forte-pianos, Editions Delatour, 2008, p. 44.

En 1789, il change à nouveau d’adresse pour le n°666 de le rue Saint-Honoré, ce que précise une annonce publiée le 28 novembre le qualifiant de “facteur de forte-piano” et non plus de clavecin. Il est certainement un temps le maître de Paul Guillaume Dackweiller (1750-1801)[1] et fréquente le voisinage de Cousineau, Naderman ou encore des Zimmermann. En 1775, il se marie avec Marie-Sophie Gossens et trois filles naîtront de cette union, dont Sophie Mercken-Hartmann – musicienne à l’origine de Six romances pour le piano et la voix. En 1776, il devient membre de la nouvelle Corporation des Tabletiers, Luthiers et Éventaillistes, dont il sera le dernier syndic en 1789, après Georges Cousineau et François Henri Clicquot.

[1] Marie-Christine et Jean-François Weber, J.K. Mercken, Premier facteur parisien de forte-pianos, Editions Delatour, 2008, p. 15

Cette célébrité des syndics luthiers qui ont précédé Mercken en cette qualité, témoigne de l’importance réelle qu’avait Mercken dans son milieu professionnel en 1788-1789. Il était devenu une référence de qualité comme en témoigne le souci de Dackweiller de mentionner sur ses pianos qu’il est son élève.

Marie-Christine et Jean-François Weber, J.K. Mercken, Premier facteur parisien de forte-pianos, Editions Delatour, 2008, p. 64

Vers 1808, il quitte Paris pour Versailles, rue d’Anjou, afin de rejoindre sa fille et son gendre Eigenschenck. Son deuxième gendre Beckers, facteur de harpes, lui succède rue Saint-Honoré puis n°3 rue du Roule, en 1818.

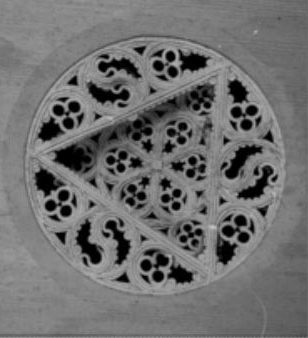

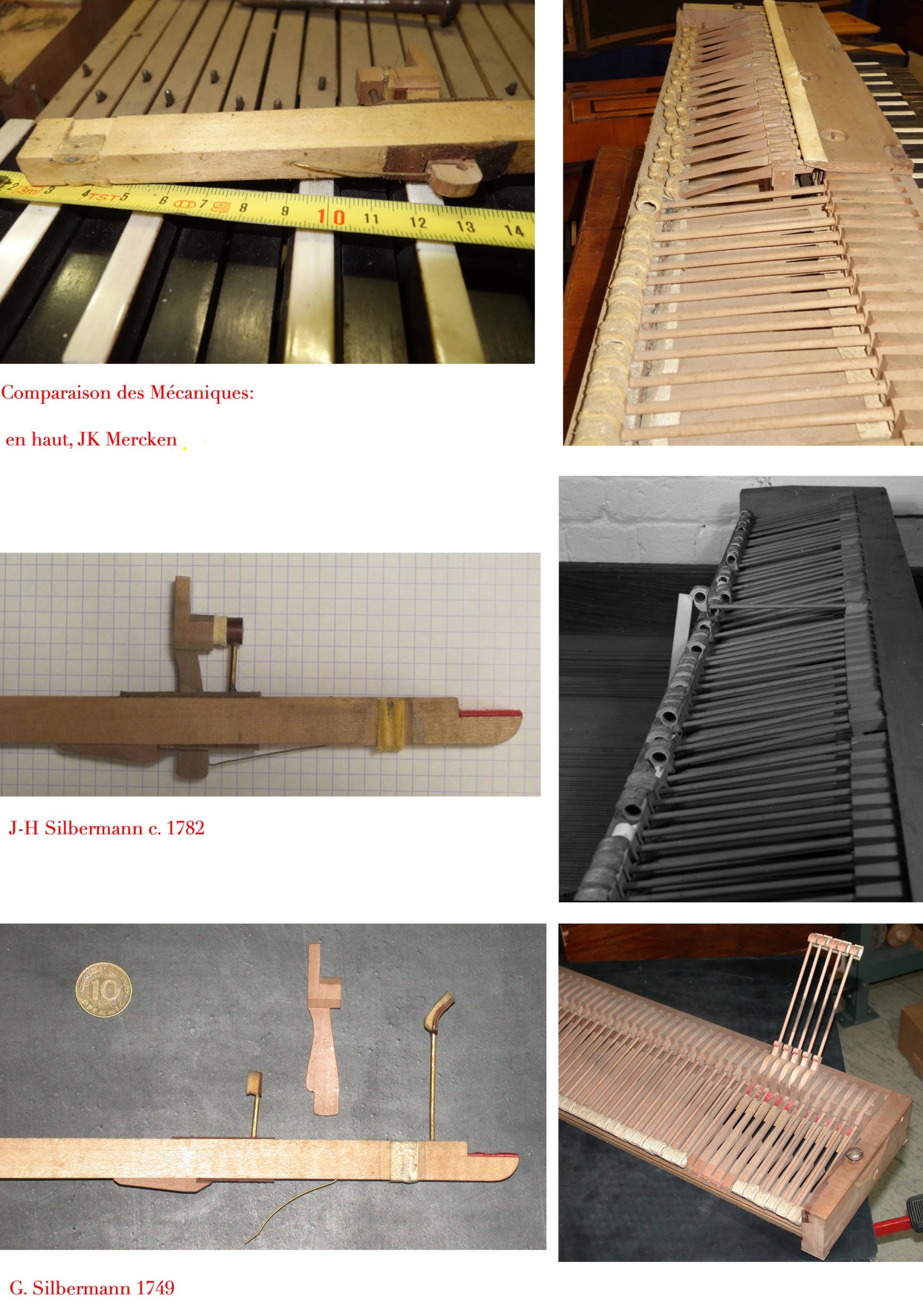

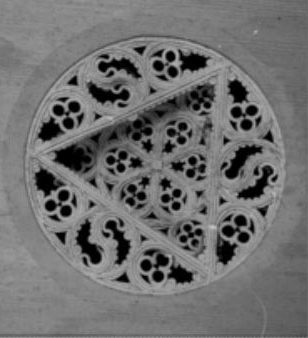

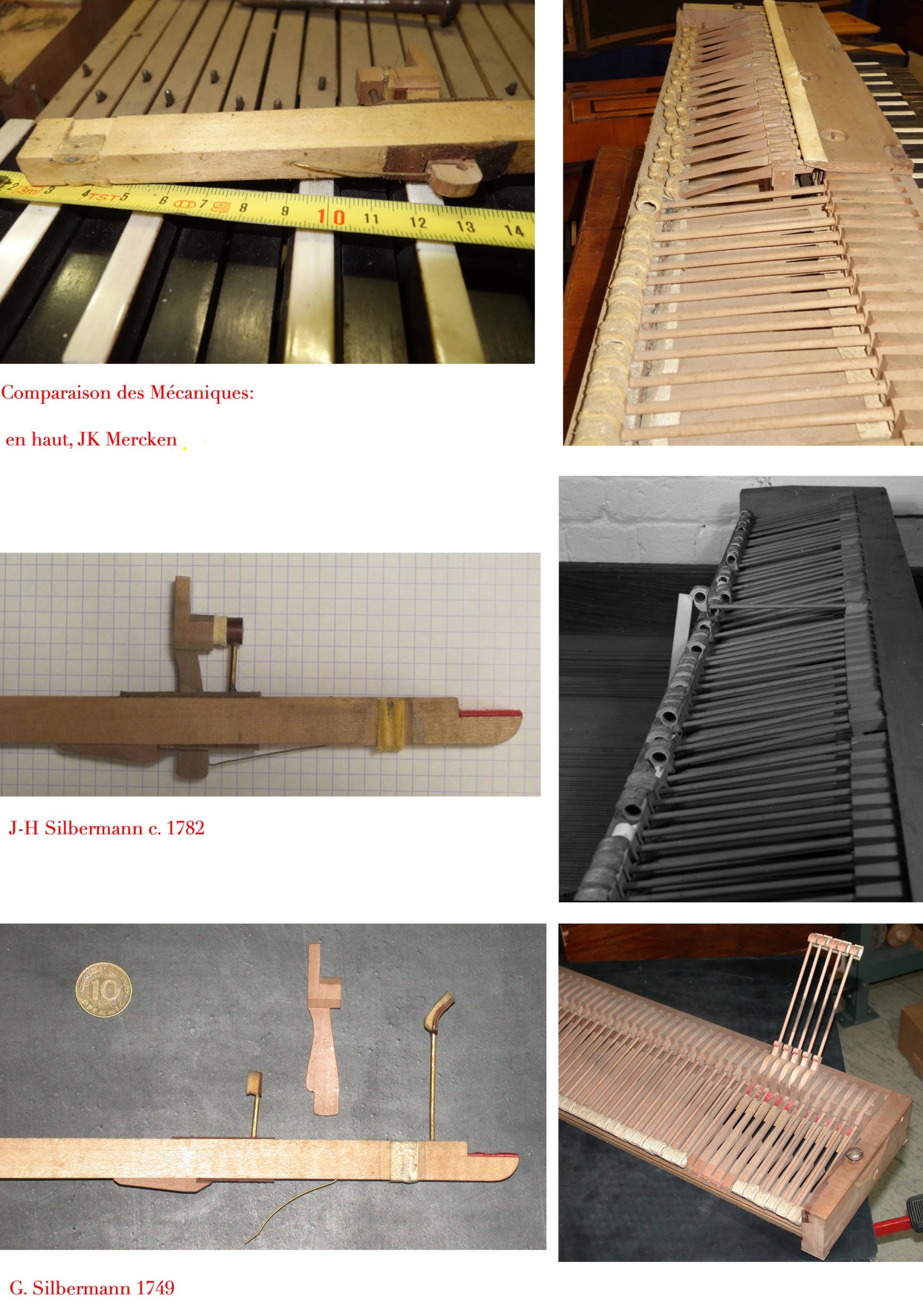

Aucune archive ne nous renseigne sur la formation de Mercken. Originaire d’Aix-la-Chapelle, plusieurs historiens considèrent qu’il pourrait avoir été en relation avec les Silbermann, et notamment sa branche strasbourgeoise[1]. De prime abord, la parenté de l’instrument en forme de clavecin de la vente Vichy Enchères avec ceux des Silbermann est incontestable. Comme le souligne l’expert Christopher Clarke, la mécanique de la moitié inférieure de son étendue est presque identique à celle des instruments de Jean-Henri Silbermann. Ces similitudes laissent penser que Mercken aurait observé des modèles Silbermann – notons qu’il y en avait quatre à Paris dès 1761. Ainsi, tout comme les modèles des Silbermann, ce piano en forme de clavecin à la “caisse plaquée de noyer, [le] sommier inversé, [les] cordes espacées régulièrement (l’espace entre unissons est quasi égale à l’espace entre deux notes) avec des étouffoirs en sautereau qui sont guidés entre les unissons, une belle rosace en trois couches de carton.”[2].

[1] Marie-Christine et Jean-François Weber, J.K. Mercken, Premier facteur parisien de forte-pianos, Editions Delatour, 2008, p. 42

[2] Christopher Clarke, étude du piano en forme de clavecin de Mercken, novembre 2021

La forme de la queue du piano en pan coupé est typique du travail de Johann Heinrich Silbermann et l’aspect de la caisse lui doit également beaucoup. Toutefois, malgré ces similitudes, Mercken s’affirme par une facture personnelle et un mode de construction différent. Ainsi, la structure interne de l’instrument de Mercken de la vente du 7 mai 2022 diffère considérablement de celle de Silbermann. Le clavier en ébène de ce piano en forme de clavecin a une mesure d’octave moins large que ceux des Silbermann. De plus, à la différence des chevalets de Silbermann, qui ont des contre-pointes sur toute l’étendue, celui de Mercken a des pointes simples pour les 23 premières notes de l’aigu. Enfin, la rosace de Mercken est plate, tandis que celles de Johann Heinrich Silbermann ont une partie centrale plus profonde. Au regard de cet instrument, Christopher Clarke estime que l’hypothèse selon laquelle Mercken aurait été en formation dans l’atelier de Silbermann est improbable, mais qu’il est possible qu’il ait examiné ou travaillé sur quelques modèles et en ait retenu certains principes constructifs.

Cet instrument nous renseigne également sur la relation de Mercken avec Christian Baumann. Ce dernier travailla pour la cour du très francophile duc Christian IV de Deux-Ponts à partir de 1766 et les 14 pianofortes de Baumann retrouvés en France – trois quarts de ses instruments connus – ont probablement été vendus grâce à l’appui du duc pendant ses séjours à Paris. Il n’est pas impensable que le duc ait ensuite pris Mercken sous son patronage. Pour Christopher Clarke, il est fort probable que Mercken ait travaillé chez Baumann en tant qu’ouvrier compagnon, Deux-Ponts se trouvant à mi-chemin entre Übach – la ville d’origine de notre facteur – et Paris. Baumann jouissait déjà d’une grande renommée, à tel point que Mozart recommanda ses pianofortes. Il eut donc l’honneur de faire partie des trois rares facteurs cités par le jeune compositeur.

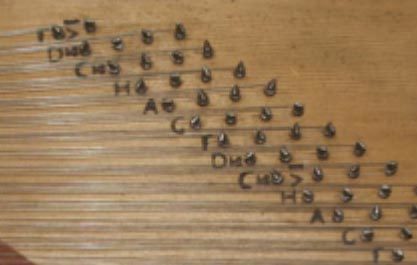

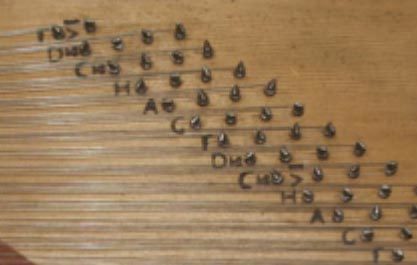

Toujours est-il que le piano en forme de clavecin de Mercken de la vente du 7 mai 2022 témoigne d’une grande connaissance du travail de Baumann. Contrairement à ceux de Silbermann, son clavier est quasiment identique à ceux des instruments de Baumann, que ce soit dans ses formes ou sa dimension de 471mm pour trois octaves. Mercken a également repris de Baumann la nomenclature et les formes des notes marquées à côté des chevilles d’accord. Les notes sont estampillées à la manière de Baumann qui les marquait au fer, alors qu’il était courant que celles-ci soient seulement inscrites à la plume. Par ailleurs, le traitement des kapseln (fourches montées sur les touches dans lesquelles pivotent les marteaux) dans la mécanique de la moitié aiguë du clavier est identique à celui mis en œuvre par Baumann :

Baumann avait une façon très particulière de faire les axes de pivotement des marteaux; un faisceau de fibres de soie non filées est collé dans une branche de la fourche en poirier, pour passer ensuite librement dans un trou un peu plus grand dans la tige du marteau prise entre les bras, puis passer dans l’autre bras sur l’extérieur duquel les fibres sont éparpillées en étoile et collées. […] Cette façon de faire est presque une marque de fabrique de Baumann. Mercken a reproduit ce procédé à la perfection.

Christopher Clarke, étude du piano en forme de clavecin de Mercken, novembre 2021

L’expert souligne également que la construction particulière du fond de caisse est analogue à celle de Baumann pour ses pianos carrés jusque vers 1785. De plus, on note que les genouillères des pianos carrés de Mercken se déplacent horizontalement comme celles de Baumann et non verticalement comme c’était l’usage. Hypothèse inédite, Christopher Clarke suggère que Baumann ait à son tour repris plusieurs inventions de Mercken. En effet, un piano carré de Baumann, probablement de 1793, possède la même mécanique aiguë que ce piano en forme de clavecin de Mercken. En outre, “il est curieux de voir que la butée des marteaux (le Prell-leiste) est garnie de peau suivant exactement les mêmes procédés que Mercken”. Cette ressemblance est particulièrement intéressante puisqu’elle donne une idée du type de pianos à queue que pouvait construire Baumann – ces derniers ayant tous disparus.

Mercken est un bel exemple de réussite sociale puisqu’il mena une vie prospère tout en jouissant de la considération des autres facteurs et musiciens. L’un des plus beaux exemples de ce succès est le tableau réalisé en 1794 par François-André Vincent figurant la célèbre cantatrice Rosalie Duplant assise devant un piano commandé à Mercken, sur lequel on peut lire “Merken Parisiis fecit 1785”. Cette inscription témoigne de la renommée dont jouissait le facteur à la fin du XVIIIème siècle, digne d’apparaître sur le portrait de la chanteuse qui bénéficiait depuis plusieurs années d’une grande notoriété. Notons également qu’il est très rare que les noms des facteurs apparaissent sur les portraits de musiciens. Véritable signe de reconnaissance, une autre peinture exposée au Salon de 1800, un portrait du compositeur François-Adrien Boieldieu par Boilly aujourd’hui conservé au Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, le représente devant un pianoforte inscrit “Mer…” – le reste étant caché par la main du portraituré. La fidélité des détails du piano amène à penser que l’instrument est également un Mercken. Enfin, la presse de l’époque rend également compte de la reconnaissance dont Mercken faisait l’objet :

Il existe […] à Paris, un Facteur nommé Mercken, demeurant aux Quinze-vingts, dont les Forte-piano sont excellents, & qui, pour la solidité et la bonté du clavier, sont préférables, on ose le dire, à la plupart de ceux d’Angleterre ; la partie du clavier surtout, si essentielle & si négligée ordinairement, y est traitée avec une perfection qui ne laisse presque rien à désirer : c’est l’aveu de tous les connaisseurs qui ont examiné les Instruments du sieur Mercken.

Journal de Paris, 24 Mars 1780, n° 84, p. 347.

Par ailleurs, ses instruments font souvent l’objet d’un grand raffinement qui témoigne d’importantes commandes. Ainsi, en 1782, Mercken fait appel à Antoine Rascalon pour orner un pianoforte d’un décor de rinceaux en verre églomisé. En ce qui concerne l’instrument en forme de clavecin de la vente Vichy Enchères du 7 mai 2022, il rend compte d’un souci certain de recherche dans le décor. Il est doté de pieds cannelés et sa remarquable marqueterie, composée de grands panneaux centraux en noyer ronceux et entourés de larges bandes transversales en arêtes de hareng, est similaire à celle de deux pianos carrés de Baumann de 1782. Ce piano de Mercken présente une marqueterie très travaillée, avec une table d’harmonie en épicéa de bonne qualité et comportant une grande et belle rosace faite de trois couches de carton dans le style rhénan. Nul doute qu’il ait été conçu pour une occasion particulière.

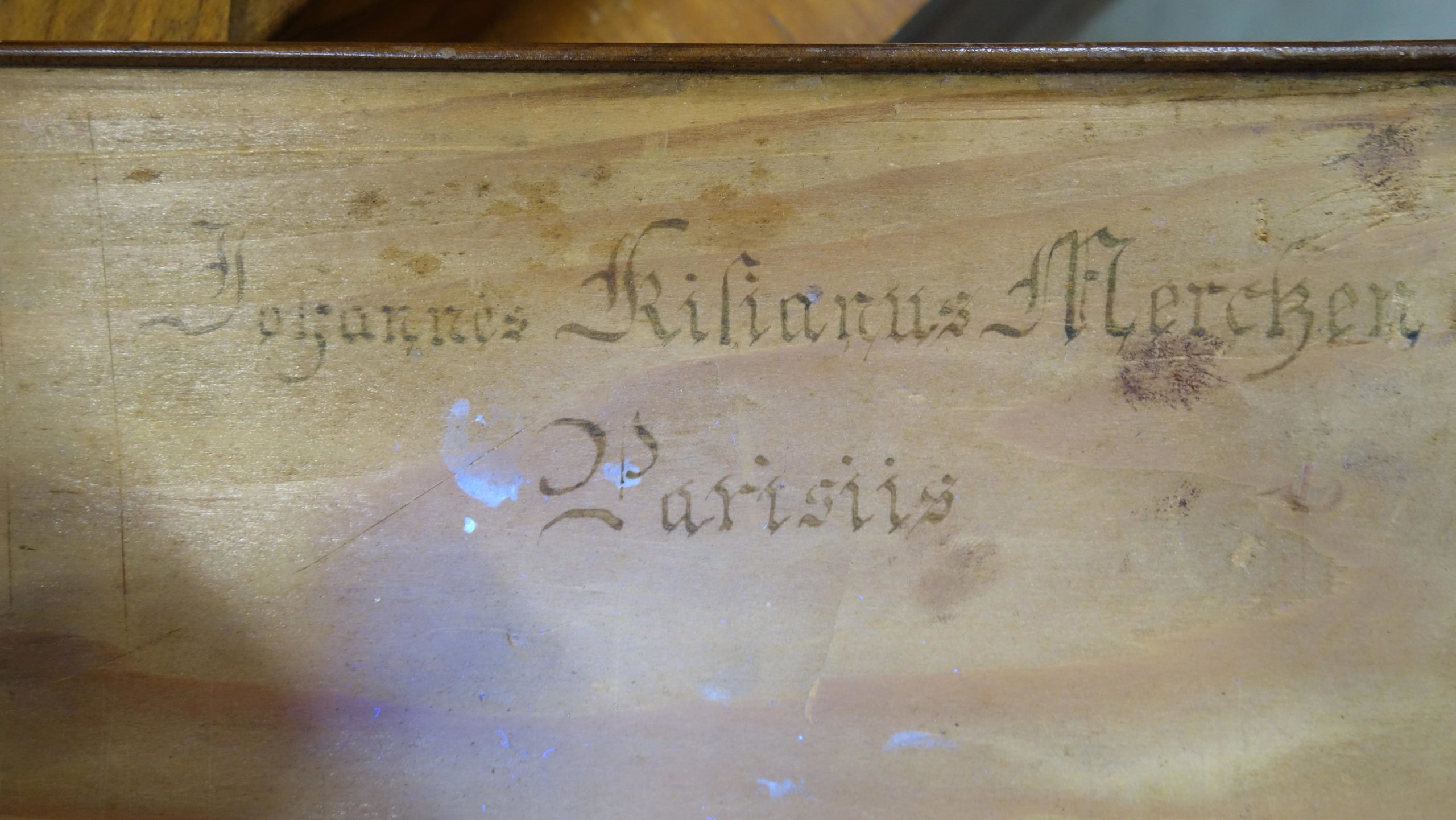

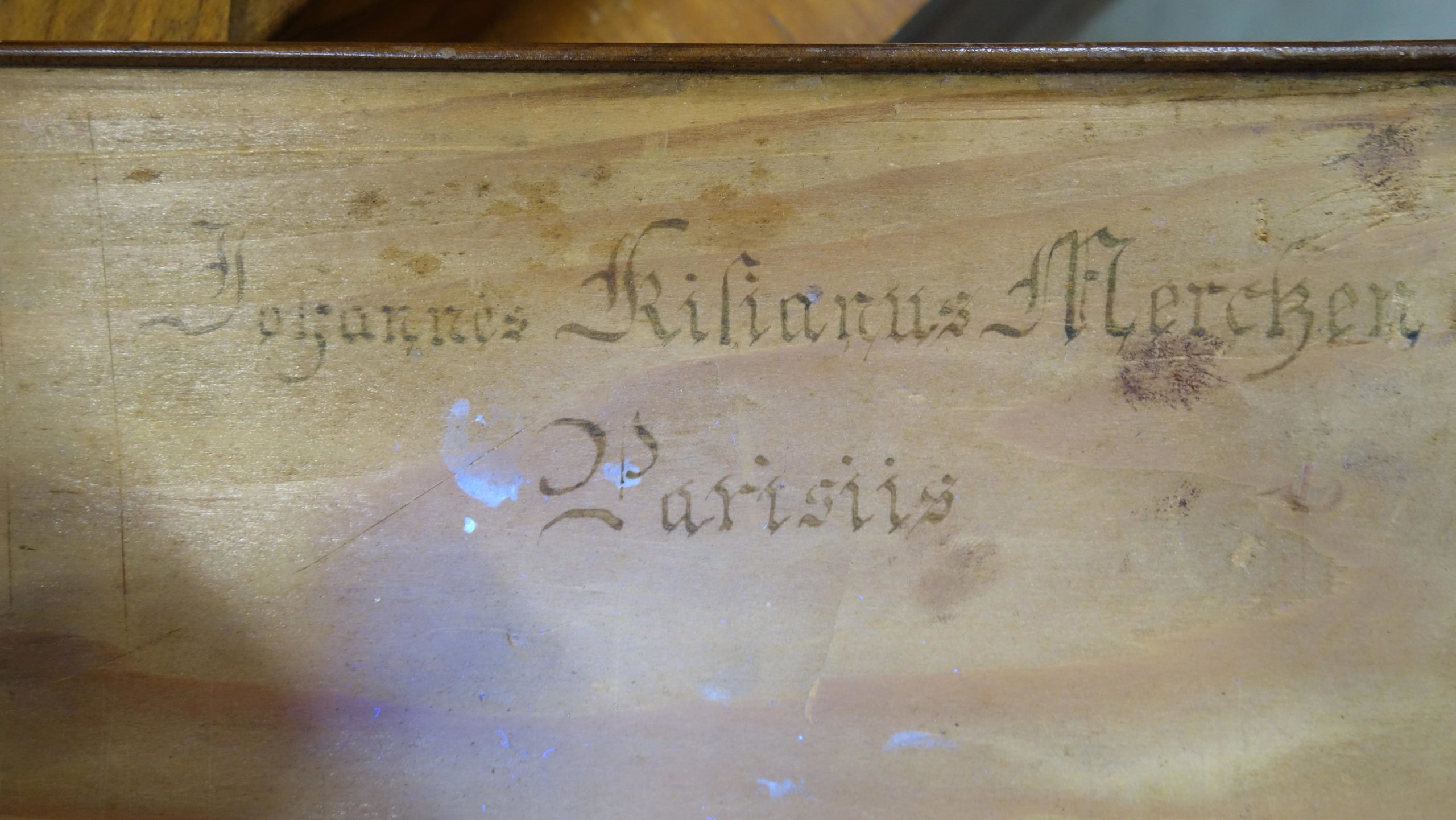

L’instrument est signé d’une belle écriture à l’encre, à l’arrière de la planche d’adresse, en haut du côté des graves : «Johannes Kilianus Mercken/Parisiis». Cette façon de faire est typique des facteurs allemands et alsaciens qui signaient parfois à la main d’une façon peu apparente et réalisaient surtout des rosaces au dessin caractéristique faisant office de signature.

Comme nous l’apprend Christopher Clarke, sur les trois pianofortes signés ayant survécu de l’atelier de Jean-Henri Silbermann – respectivement datés de 1776, 1782 et 1789 – seul l’instrument de 1782 porte une étiquette sur la table d’harmonie. Celle du modèle de 1776 se trouve sur la mécanique et celle du piano de 1789 est collée sous le couvercle de la boîte à outils. Il en est de même pour les instruments de Gottfried Silbermann, discrètement signés manuscritement à l’intérieur.

“Je ne pense pas que Mercken ait voulu cacher sa signature; il n’a fait que respecter les conventions propres à ce genre d’instrument (rosace en carton, signature à l’intérieur de l’instrument), tout comme il a scrupuleusement respecté les conventions propres au piano-fortes carrés anglais, signés, eux, avec ostentation sur le devant de la planche du clavier.”

Christopher Clarke, étude du piano en forme de clavecin de Mercken, novembre 2021

Malgré sa signature, l’instrument n’est pas daté mais plusieurs indices dans la facture laissent supposer que le piano a été réalisé en tout début de carrière, lors de l’installation de Mercken à Paris, vers 1767. L’expert Christopher Clarke estime qu’il s’agit très certainement d’un instrument prototype, puisque la facture de Mercken n’est pas encore entièrement assurée, d’où quelques maladresses et hésitations observables. Signalons que les mesures correspondent au pied du Roi – celles suivies par des facteurs allemands et alsaciens comme J.H. Silbermann, C. Zell ou J.A. Stein – dont Mercken semble s’inspirer en début de carrière.

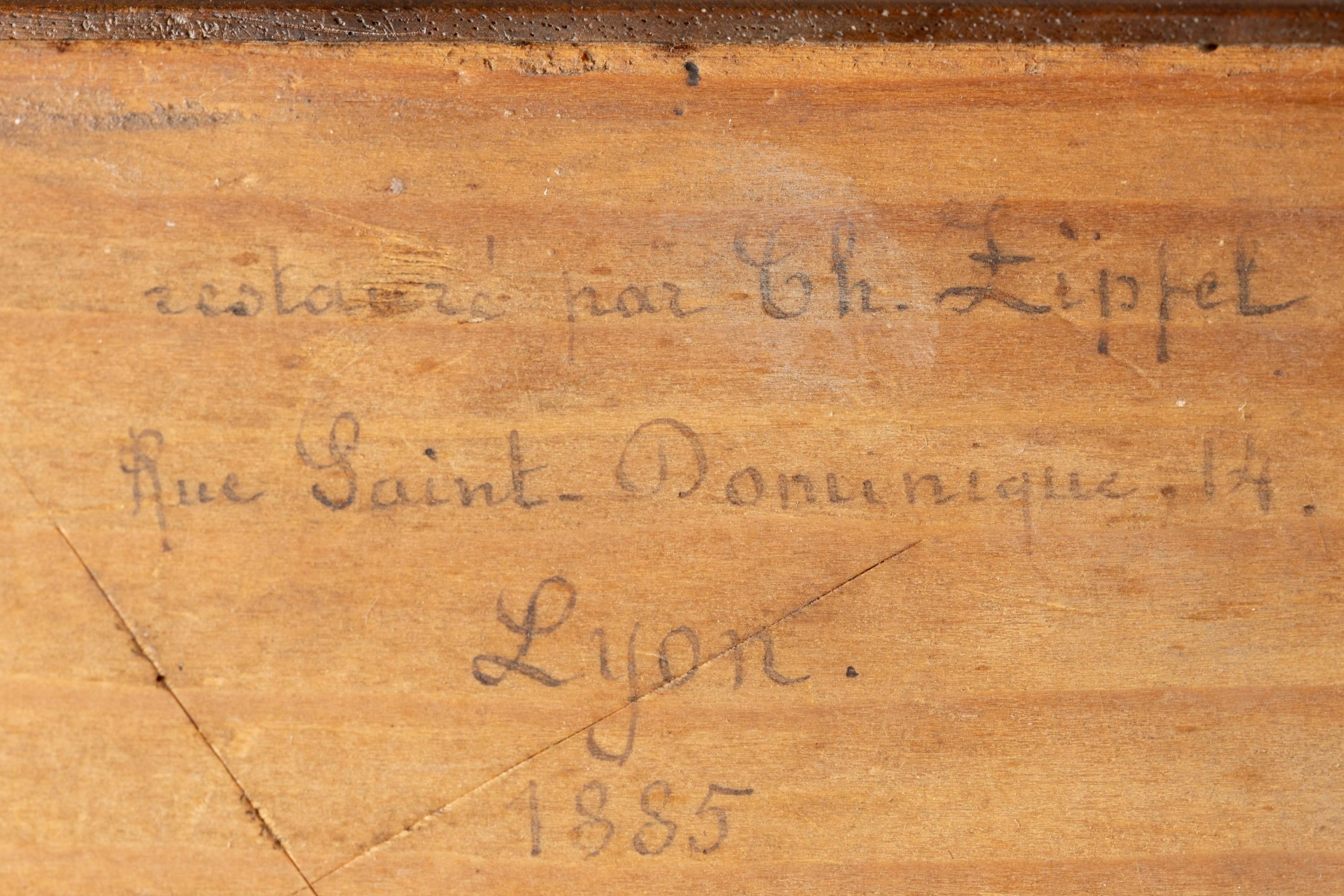

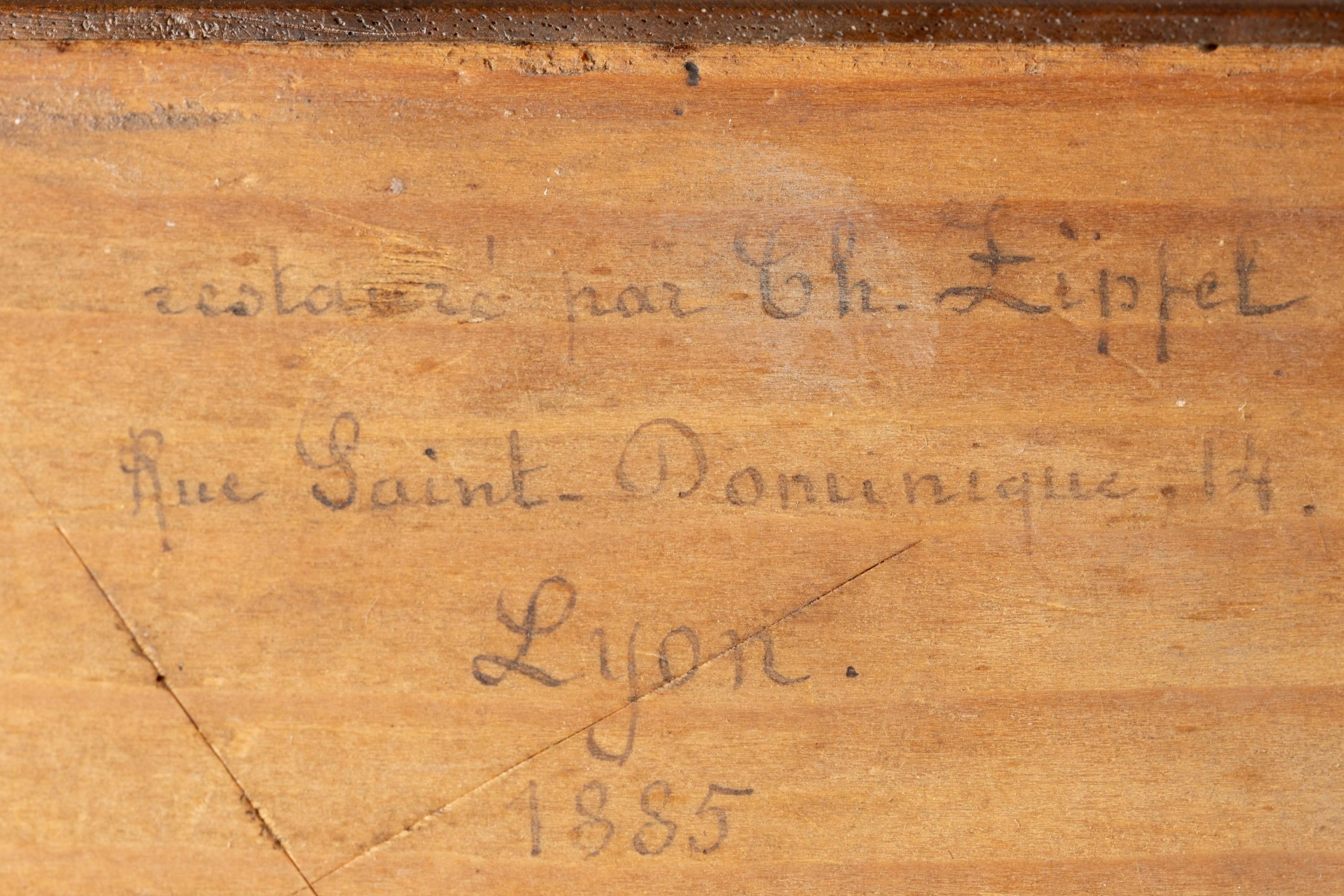

Toujours selon l’expert, une seconde hypothèse pourrait être que ce piano ait été réalisé comme chef-d’œuvre d’entrée dans la Corporation des Tabletiers, Luthiers et Éventaillistes en 1776. Cependant, les quelques hésitations et lacunes observées sur l’instrument, ainsi que la nomenclature à l’allemande des notes écrites près des chevilles d’accord, éloignent cette éventualité. Kerstin Schwarz, spécialiste reconnue des Silbermann, considère également que l‘instrument est l’œuvre d’un jeune homme. Signalons que l’instrument a été restauré par Zipfel en 1885, comme nous l’apprend l’inscription à l’encre «restauré par Ch. Zipfel/Rue Saint-Dominique 14/Lyon./1885».

Stylistiquement, ce piano est proche du travail allemand, que ce soit dans son style de caisse, de rosace et jusque dans sa nomenclature allemande. Autour des années 1760-1770 en France, les pianofortes sont encore considérés comme des instruments étrangers et ceux en forme de clavecins sont traditionnellement allemands. D’origine allemande et fraichement installé aux Quinze-Vingts à Paris probablement en 1767, il n’est pas étonnant que Mercken ait réalisé ce superbe instrument dans un style germanique.

La facture de son piano en forme de clavecin est entièrement compatible avec une construction à cette date ; plusieurs indices suggèrent que Mercken, fraîchement arrivé dans la capitale, aurait voulu frapper les esprits en présentant un grand instrument, ambitieux sur les plans décoratifs et musicaux.

Christopher Clarke, Etude du pianoforte en forme de clavecin de Mercken

Le fort empreint germanique, que ce soit dans sa conception, sa rosace, sa nomenclature des notes estampillées sur le sommier de chevilles, oriente vers une datation juste après l’arrivée de Mercken à Paris en 1767, avant qu’il ne se conforme au goût parisien. Compte tenu de son style et de ses principes constructifs propres au travail de Baumann, Christopher Clarke estime qu’il est probable que Mercken ait réalisé cet instrument à son arrivée à Paris, peut-être dans une caisse construite au préalable en Allemagne, directement après sa sortie de l’atelier de Baumann. Il n’est pas impossible, si tel était le cas, que la construction de ce pianoforte ait été encouragée à Paris par le duc Christian IV. Cet instrument serait ainsi une œuvre de jeunesse, car dès 1770, Merken ne fabrique plus que des pianos carrés d’inspiration anglaise, du type de celui de 1781 de la vente Vichy Enchères du 7 mai 2022.

Qu’il ait ensuite modifié son style de travail pour s’adapter au marché parisien n’est pas surprenant, et il existe de nombreux exemples contemporains de fabricants émigrés adoptant le style de leur nouveau pays, tels que Zumpe à Londres et Taskin à Paris.

En outre, ce piano est le théâtre d’expérimentations menées par notre facteur. Sur le plan musical, il offre notamment une étendue exceptionnelle pour l’époque, puisqu’il possède un sol aigu. Ces expérimentations laissent penser que l’instrument a été réalisé tôt dans sa carrière, à un moment où Mercken cherchait les moyens de mettre en forme l’instrument idéal.

Cet pianoforte en forme de clavecin de Mercken est également unique par la cohabitation de deux types de mécaniques de piano : dans la moitié basse, une mécanique à échappement similaire à celles des Silbermann, et dans la moitié aiguës, une mécanique sans échappement de type Prellmechanik. Cette dernière fonctionne avec un emploi de têtes pleines “à la place des rouleaux en carton” que l’on trouve encore dans la moitié grave, permettant “une meilleure émission sonore des notes aiguës”. D’après Christopher Clarke, ce mécanisme a sans doute été installé par Mercken pour remplacer la mécanique à la Silbermann à cet endroit. Un peigne compatible avec les marteaux d’une mécanique de type Silbermann est visible, mais désuet. Mercken a probablement réalisé ce premier système vers 1768, avant de le modifier, certainement dans l’optique de contrer les critiques de l’époque jugeant ce type de mécaniques à échappement trop lourds, lents et fatigants à jouer. En 1767, on pouvait effectivement lire dans la presse :

Depuis un certain temps on fait venir à Paris des clavecins à marteau, appelés forte-piano, travaillés très-artisement, à Strasbourg, par le fameux Silbermann. Ces clavecins […] sont fort agréables à entendre, […] mais ils sont plus pénibles à jouer, à cause de la pesanteur du marteau, qui fatigue les doigts, & qui même rend la main lourde avec le temps.

«Facteur de Clavecins» écrit par M. du Moutier pour le «Dictionnaire portatif des Arts et Métiers» publiée à Amsterdam en 1767

Ainsi, ce type de critiques a pu conduire Mercken à modifier la mécanique des aiguës afin de proposer un piano adapté au goût des Français, avec un jeu plus léger et rapide. Selon Christopher Clarke, il se pourrait que cette transformation ait été réalisée avant que l’instrument ne quitte l’atelier et il est certain qu’elle est l’œuvre de Mercken :

The Prell-leiste is made from the same rather unusually-figured pearwood as was used for parts of the keyframe and the treble hammer-heads are worked in a similar manner to the saddles that receive the cardboard rolls of the bass hammer-heads.

A grand piano by J. K. Mercken, Paris c.1768: context and comparison with instruments by G. & J-H. Silbermann and C. Baumann

Ces observations, ainsi que la belle signature certainement calligraphiée par un professionnel, permettent également de réfuter l’idée selon laquelle Mercken aurait modifié le piano d’un autre facteur. Le piano présente une mécanique divisée à la fois rare et étonnante, qui semble à nouveau tisser un lien avec Christian Baumann, puisque le seul autre piano connu possédant des mécaniques distinctes pour les graves et les aiguës est un modèle carré de Baumann, daté vers 1790[1].

[1] Christopher Clarke, Etude du pianoforte en forme de clavecin de Mercken. Le piano de Baumann appartient à la collection Pooya Radbon, Allemagne. Cette collection renferme également un piano carré de Mercken, 1785

La découverte de ce nouvel instrument de Jean-Kilien Mercken est d’une grande importance pour l’histoire de la facture française de pianos. Elle éclaire également une nouvelle partie de la production de Mercken – le premier facteur parisien de pianofortes – puisqu’aucun clavecin ou piano en forme de clavecin ne lui était connu jusque-là. Cet instrument pourrait ainsi être le premier pianoforte de France. Vichy Enchères vous donne rendez-vous le samedi 7 mai 2022 pour assister à la vente de cet instrument historique.

Which is the oldest piano made in France? It is on this question that the discovery of a previously unknown instrument by Jean-Kilien Mercken (1743-1819) invites us to reflect. This “pianoforte in the form of a harpsichord” – as grand pianos were called before the 19th century – puts the history of French piano making into perspective and sheds light on a new aspect of the production of Mercken, who was known only for his square pianofortes. Vichy Enchères invites you to lift the veil on this enigmatic example – probably the first French grand piano – in the context of the history of the emergence of the instrument in the 18th century.

Within the family of string and keyboard instruments, the piano is in a way the result of the mechanization of the tympanon, a struck strings instrument, which allowed for dynamic expression, something that couldn’t be achieved with plucked strings. Its cousin the clavichord, whose strings are struck at one end by metal blades called “tangents”, already had dynamic possibilities but its quiet sound was a weakness compared to other instruments. It was around 1700, in Florence, that the pianoforte was born in the workshop of Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655-1731). While in the service of Prince Ferdinando de’ Medici, Cristofori invented the mechanism still in use on the modern piano. With this mechanism, strings are struck by skin-covered hammer-heads connected to the keys, and a release system allows the hammer-heads to fall far back after striking the strings, rather than staying close.

These innovations were significant since they made it possible to gradually increase the dynamic from piano to forte, hence the name pianoforte. In an inventory of 1700, the first pianofortes of Cristofori are named “arpicembalo” (or “harp-harpsichord”) because they sounded like the harp. In 1711, Scipione Maffei published an article in the Giornale de’ letterati d’Italia which described a “Gravicembalo [grand harpsichord] col piano, e forte” and included the design of its mechanism. Cristofori perfected it in the 1720s and this model met with some success in Italy and also in Portugal and Spain, where it was introduced by Domenico Scarlatti and Carlo Brosi, known as Farinelli.

It was in Saxony that the new instrument really spread and developed. In 1705, Pantaleon Hebenstreit (1668-1750) made a giant tympanon which he presented to the court of Louis XIV. The audience was dazzled by the variety of sounds produced with the hammer-heads, which were either made of hard wood or lined with wool, and especially by the resonance of the un-muted strings. The king, who was also impressed, decided to name the instrument “Pantalon” after its inventor. At the same time, the German Christopher Schröter made two unfinished models of mechanical pianos with hammer-heads in 1717 and presented them to the court of Saxony in 1721. The ancestor of the modern piano was actually distributed by German organ makers (who also made harpsichords and clavichords), the most famous of which was Gottfried Silbermann (1683–1753). It was to him that Hebenstreit turned for the exclusive manufacture of his “Pantalons” and, at the same time, Silbermann had the idea of making some pianofortes in the shape of harpsichords, probably fitted with mechanisms based on the design by Cristofori – which was published in Germany in 1725.

Johann Sebastian Bach tried them but found them too heavy and slow, which led Silbermann to modify the mechanisms and introduce levers to lift the dampers, in order to produce a sound reminiscent of the much appreciated one of the “pantalon”. This model received Bach’s approval and four examples of it were presented in 1746 to King Frederick in Potsdam. Gottfried Silbermann was for long considered the inventor of the pianoforte, and his nephew Johann Heinrich Silbermann, established with his brother Johann Andreas in Strasbourg, later reproduced most aspects of this model. In parallel with the work of the Silbermanns, which centred on the harpsichord-shaped piano in the tradition of Cristofori, other organ builders were inspired by the timbres of the “pantalon” and made instruments producing a “sonic rainbow” using hardwood or leather-lined hammer-heads. Judging the mechanisms with the release device too heavy and slow, they made them without release, poorer in nuances as a result, but extremely fast. Around 1758, a pupil of Gottfried Silbermann, Christian Ernst Friederici (1709-1780), had the idea of combining the possibilities of the “pantalon” with the shape of the clavichord and named this new instrument the “Fortbien”.

Unlike German makers, who had experience with expressive keyboards and varied timbres, French makers were less versatile and innovative and continued to produce exclusively harpsichords and spinets during the first two thirds of the 18th century. The clavichord remained unknown in France. However, in 1716, organ builder Jean Marius presented to the Paris Academy of Sciences four instruments with a mechanism featuring jacks instead of hammer-heads, which he called “mallet harpsichords” – but which he did not produce as he was not a member of the Community of Master Makers of Musical Instruments. Therefore, in France, those interested in purchasing a pianoforte had to source it from German and Alsatian makers for harpsichord-shaped models, and from 1765, from English makers for square-shaped ones. Conversely, makers producing pianofortes in France, like Mercken, were particularly rare. As a result, the oldest grand piano preserved in France, at the Musee de la Musique, was not made in France but comes from Switzerland, where it was made in 1763 by Johann Ludwig Hellen.

As Marie-Christine and Jean-François Weber indicate in their reference work on Mercken, the first known pianoforte built in Paris is a square model by Mercken dated 1770 and kept at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers de Paris. Léon Pillaut wrote, as early as 1889, in the catalogue of the Universal Exhibition:

The oldest piano is a French one by Mercken (Paris 1770); it is of meticulous craftsmanship and very elegant.

The discovery of this pianoforte in the shape of a harpsichord puts things into perspective, since this instrument was most probably made before the one in the collection of the Arts et Métiers, around 1767-68. It would therefore be the oldest French grand piano to have emerged. It is also the only instrument known by Mercken that is in the form of a harpsichord. Apart from this grand piano, few other French examples from this period are known to us. Pascal Taskin made several that he presented to the Academy of Sciences, but only between 1776 and 1791.

Whilst the harpsichord was in vogue in European music and courts in the 17th and 18th centuries, the pianoforte took centre stage from the last third of the 18th century. Nevertheless, it was at the harpsichord that Marie Antoinette was portrayed in 1769 by Franz Xaver Wagenschön, and the instrument was still present in the Conversation musicale of Trinquesse dated 1774. It is worth noting that, before the 1770s, the pianoforte remained quite rare on French soil. However, around 1765, the German Johannes Zumpe began to manufacture small square pianos in London, inspired by Friederici’s “Fortbien” and fitted them with a simplified mechanism without release and hammer-heads covered with hide. These instruments were the first pianos designed for mass production. Musicians and amateurs, English aristocrats and bourgeois, shortly followed by the French, were almost instantly seduced by their charming sound, their price three times lower than the harpsichord, their elegance and their small size. The first public concert in Paris featuring a piano was given in 1768, at the Concert Spirituel[1] and immediately afterwards Jean-Chrétien Bach composed concertos for harpsichord or pianoforte. Madame Brillon de Jouy, a great keyboard virtuoso, was one of the first owners of such instrument. From the 1770s, advertisements for pianofortes became more common in French newspapers and the piano gradually replaced the harpsichord, leading to the disuse of the latter by the end of the century.

The phenomenon of the square pianoforte was in part social, as the instrument became a distinctive symbol of good taste and high social status, particularly within the bourgeoisie.

Increasingly before the Revolution, women of the world were being portrayed at the pianoforte, which shows how much the instrument was seen as an indispensable accessory of modernity and of feminine fashion, superseding the previous tradition of portraits at the harpsichord in vogue between 1690 and 1770. It is worth noting that the dominant model of instrument pictured is unquestionably the square piano.

Florence Getreau. Les images de pianistes en France, 1780-1820. Musique, images, instruments, Paris: Ed. Klincksieck; Paris: Laboratoire d’organologie et d’iconographie musicale CNRS, 2009, Le pianoforte en France 1780-1820, 11, pp.136-149.

[1] Marie-Adélaïde de Place. Le piano-forte en France de 1760 à 1812. In: École pratique des hautes études. 4e section, Sciences historiques et philologiques. Annuaire 1976-1977, p.1117.

Mercken seems to be the first Parisian maker to have copied English square pianos, anticipating, with foresight, a booming market. Before the discovery of the example in the Vichy Enchères sale of May 2022, we were not aware of any pianoforte by him in the form of a harpsichord. It was not until the 1790s and Erard that the grand piano took off – with Haydn and Beethoven being amongst its earliest proponents. If Erard chose to adopt this type of piano, it was mainly to produce a more powerful instrument that could rival other instruments in the orchestra.

Jean-Kilien Mercken (1743-1819), also known as Johann Kilian Mercken or Johannes Kilianus Mercken, was born in Übach, north of Aix-la-Chapelle, which was then part of Austria. Like many German instrument makers, Mercken migrated to France. He settled in Paris around 1767, aged 25[1]. His origins and his career path up to that point did not allow him to freely exercise his trade, which was governed by the Community of Musical Instrument Makers. He first set up shop as a harpsichord maker in the protected enclosure of the Royal Quinze-Vingts Hospital – just like Joseph Raoux – and moved to rue du Chantre around 1780, as evidenced by the inscription on the square pianoforte of 1785 kept at the Musee de la Musique.

[1] Marie-Christine et Jean-François Weber, J.K. Mercken, Premier facteur parisien de forte-pianos, Editions Delatour, 2008, p. 44.

He moved again in 1789, to n°666 rue Saint-Honoré, as indicated in an advertisement published on 28 November, which referred to him as a “forte-piano maker” and no longer a harpsichord maker. He was at some point the tutor of Paul Guillaume Dackweiller (1750-1801)[1] and mixed in the circles of Cousineau, Naderman and even the Zimmermanns. In 1775 he married Marie-Sophie Gossens and three daughters were born of this union, including Sophie Mercken-Hartmann – the composer of Six romances for piano and voice. In 1776 he became a member of the new Corporation des Tabletiers, Luthiers and Eventaillistes, of which he was the last trustee in 1789, after Georges Cousineau and François Henri Clicquot.

[1] Marie-Christine et Jean-François Weber, J.K. Mercken, Premier facteur parisien de forte-pianos, Editions Delatour, 2008, p. 15

The famous makers who preceded Mercken in the role of trustee attest to the status that Mercken had attained in his professional circles in 1788-1789. He had become a reference for quality, as evidenced by Dackweiller’s proud mention on his pianos that he was a pupil of his.

Marie-Christine et Jean-François Weber, J.K. Mercken, Premier facteur parisien de forte-pianos, Editions Delatour, 2008, p. 64

Around 1808, he left Paris for Versailles, settling on rue d’Anjou, to join his daughter and son-in-law Eigenschenck there. His second son-in-law, Beckers, a harp maker, succeeded him at rue Saint-Honoré and then, in 1818, at n°3 rue du Roule.

There are no records regarding the training of Mercken. He was originally from Aix-la-Chapelle, and several historians consider that he could have been in contact with the Silbermanns, and in particular the Strasbourg branch of the family[1]. ]. Indeed, one is immediately struck by the similarity between the harpsichord-shaped instrument in the Vichy Enchères sale and those of the Silbermanns. As expert Christopher Clarke points out, the mechanism of the lower half of its range is almost identical to those of Jean-Henri Silbermann’s instruments. These similarities suggest that Mercken studied Silbermann examples – and it is worth noting there were four of them in Paris as early as 1761. Therefore, just like the Silbermann examples, this harpsichord-shaped piano has a “walnut veneered body, inverted soundboard, regularly spaced strings (the space between unisons is almost equal to the space between two notes) with jack dampers which are guided between the unisons, and a beautiful rosette with three layers of cardboard.”[2].

[1] Marie-Christine et Jean-François Weber, J.K. Mercken, Premier facteur parisien de forte-pianos, Editions Delatour, 2008, p. 42

[2] Christopher Clarke, étude du piano en forme de clavecin de Mercken, novembre 2021

The shape of the tail of the cutaway piano is typical of the work of Johann Heinrich Silbermann and the appearance of the body also owes him a lot. However, despite these similarities, Mercken asserted himself through an individual approach and a different method of construction. Therefore, the internal structure of the Mercken instrument in the sale of 7 May 2022 sale differs significantly from that of Silbermann’s production. The ebony keyboard of this harpsichord-shaped piano has a smaller number of octaves than Silbermann’s instruments. In addition, unlike the Silbermann bridges, which have two pins per note across the entire range, the Mercken bridge has single pins for the first 23 treble notes. Finally, Mercken’s rosette is flat, while those of Johann Heinrich Silbermann have a deeper central part. In light of this instrument, Christopher Clarke considers the theory that Mercken would have trained in Silbermann’s workshop improbable, and that is it more likely he would have examined or worked on a few examples and adopted some of their principles of construction..

This instrument also tells us about Mercken’s relationship with Christian Baumann. The latter worked for the court of the very Francophile Duke Christian IV of Deux-Ponts from 1766 and the 14 pianofortes of Baumann found in France – three quarters of his known instruments – were probably sold thanks to the support of the Duke during his stays in Paris. It is not impossible that the Duke then took Mercken under his wing. According to Christopher Clarke, it is very likely that Mercken worked at Baumann’s as a journeyman, Deux-Ponts being halfway between Übach – our maker’s home town – and Paris. Baumann already enjoyed a great reputation, so much so that Mozart recommended his pianofortes; he had the rare privilege of being one of three makers referenced by the young composer.

Regardless, the piano in the shape of a harpsichord by Mercken in the sale of 7 May 2022 demonstrates a great understanding of Baumann’s work. Contrary to those of Silbermann, its keyboard is almost identical to those of Baumann’s instruments, whether in its form or dimension of 471mm for three octaves. Mercken also took from Baumann the nomenclature and shapes of the notes placed next to the tuning pegs. The notes are branded in the manner of Baumann, with an iron, whereas it was common for these to be only inscribed in ink. Moreover, the construction of the kapseln (forks mounted to the keys on which the hammer-heads rotate) in the mechanism of the treble half of the keyboard is identical to that of Baumann:

Baumann had a very particular way of making the rotating axes of the hammer-heads; a bundle of unspun silk fibres is glued to one of the tines of the pearwood fork, so it can pass freely through a slightly larger hole in the shaft of the hammer-head caught between the arms, and then pass through the other arm on the outside of which the fibres are scattered in the shape of a star and glued. […] This way of doing things is almost a trademark of Baumann. Mercken has reproduced this process to perfection.

Christopher Clarke, Analysis of a harpsichord-shaped piano by Mercken, November 2021

The expert also points out that the particular construction of the bottom of the body is similar to that of Baumann’s square pianos until around 1785. In addition, the knee levers of Mercken’s square pianos move horizontally like those of Baumann and not vertically as was customary at the time. Christopher Clarke put forward the new theory that Baumann in turn copied several innovations by Mercken. Indeed, a square piano by Baumann, probably from 1793, has the same treble mechanism as our harpsichord-shaped piano by Mercken. In addition, “it is odd to see that the stops of the hammer-heads (the Prell-leiste) are lined with hide, a innovation pioneered by Mercken”. This similarity is particularly interesting since it gives an idea of the type of grand pianos Baumann used to make; the actual instruments have unfortunately not survived.

Mercken is a fine example of social success since he led a prosperous life and was well respected by other makers and musicians. One of the finest examples of this success is the painting produced in 1794 by François-André Vincent depicting the famous singer Rosalie Duplant seated in front of a piano commissioned from Mercken, on which we can read the inscription “Merken Parisiis fecit 1785”. This inscription attests to the fame enjoyed by the maker at the end of the 18th century, as his name was worthy of appearing on the portrait of a singer who had enjoyed great success for several years. It is also worth noting that it is very rare for the names of the instrument makers to appear on the portraits of musicians. A further sign of recognition is another painting exhibited at the Salon de 1800, a portrait of the composer François-Adrien Boieldieu by Boilly now kept at the Museum of Fine Arts in Rouen, representing him in front of a pianoforte with the inscription “Mer…” – the rest being hidden by the hand of the sitter. The detailed representation of the piano points to the instrument also being a Mercken. The celebrity that Mercken enjoyed is also in evidence in the press of the time:

There is […] in Paris, a maker named Mercken, residing in the Quinze-vingts, whose Forte-pianos are excellent, & which, for the strength and the sound quality of the keyboard, are preferable, one dares to say, to most of those from England; the part of the keyboard especially, so essential & so often neglected, is manufactured with a perfection that leaves almost nothing to be desired: this is the confession of all the connoisseurs who have examined the Instruments of Sieur Mercken.

Journal de Paris, March 24, 1780, n° 84, p. 347.

In addition, his instruments are often very refined which suggests they were important commissions. For instance, in 1782, Mercken called upon Antoine Rascalon to decorate a pianoforte with a gilded glass scroll. Similarly, the harpsichord-shaped instrument in the Vichy Enchères sale of 7 May 2022 shows a focus on its ornamentation. It has fluted legs, and its remarkable inlays, composed of large central panels of burr walnut framed by wide transverse herringbone strips, is similar to that of two square pianos by Baumann from 1782. This Mercken piano has a very elaborate inlay design, with a soundboard in good quality spruce and featuring a large and beautiful rosette made of three layers of cardboard in the Rhenish style. It was undoubtedly made for a special occasion.

The instrument is signed “Johannes Kilianus Mercken/Parisiis” in beautiful ink handwriting, on the back of the address plate at the top of the bass side. This style of signature is typical of German and Alsatian makers who sometimes signed by hand in an inconspicuous manner, and most often made rosettes with a characteristic design that acted as a signature.

As Christopher Clarke tells us, of the three surviving signed fortepianos from the workshop of Jean-Henri Silbermann – dated 1776, 1782 and 1789 – only the 1782 instrument bears a label on the soundboard. The label of the 1776 instrument is on the mechanism and the one of the 1789 piano is glued under the lid of the toolbox. The same goes for Gottfried Silbermann’s instruments, discreetly signed by hand on the inside.

“I don’t think Mercken wanted to hide his signature; he only followed the conventions attached to this type of instrument (cardboard rosette, signature inside the instrument), just as he scrupulously followed the specific conventions for the English square pianofortes, signed, on the other hand, ostentatiously on the front of the keyboard panel.”

Christopher Clarke, Analysis of a harpsichord-shaped piano by Mercken, November 2021

Despite being signed, the instrument is not dated, but several clues in its manufacture suggest that the piano was made at the very beginning of Mercken’s career, when he first settled in Paris around 1767. The expert Christopher Clarke believes that it is most likely a prototype instrument, based on the fact that Mercken’s craftsmanship is not yet fully assured, hence some noticeable clumsiness and hesitation in its making. It is worth noting that the measurement system used here is the King’s foot – those followed by German and Alsatian makers such as J.H. Silbermann, C. Zell or J.A. Stein – which Mercken seems to have used at the start of his career.

Still according to our expert, a second theory could be that this piano was made as a masterpiece for entry into the Corporation des Tabletiers, Luthiers et Eventaillistes in 1776. However, the few hesitations and shortcomings visible on the instrument, as well as the German-style nomenclature of the notes written near the tuning pegs, rule out this theory. Kerstin Schwarz, an acknowledged specialist on Silbermann, also considers the instrument to be the work of a young man. The instrument was restored by Zipfel in 1885, as the inscription in ink “restaure par Ch. Zipfel/Rue Saint-Dominique 14/Lyon./1885” indicates.

Stylistically, this piano is close to German work, from the style of its body, or its rosette to its German nomenclature. Around the years 1760-1770 in France, pianofortes were still considered foreign instruments and those in the form of harpsichords were traditionally German. Being of German descent himself, and having only just arrived in Paris at the Quinze-Vingts probably in 1767, it is not surprising that Mercken would have made this superb instrument in the German style.

The craftsmanship of his harpsichord-shaped piano is entirely compatible with a construction of this date; several clues suggest that Mercken, having freshly arrived in the capital, would have liked to make a striking appearance by presenting a large instrument, ambitious both decoratively and musically.

Christopher Clarke, Analysis of a harpsichord-shaped piano by Mercken, November 2021

The strong Germanic influence, whether in the design, the rosette, and the nomenclature of the notes branded next to the tuning pegs, points to a manufacturing date of just after Mercken’s arrival in Paris in 1767, before he conformed to the Parisian taste. Given that its style and construction methods are akin to Baumann’s work, Christopher Clarke believes that it is likely that Mercken made this instrument when he arrived in Paris, perhaps using a body previously built in Germany, just after leaving Baumann’s workshop. It is possible, if this were the case, that the construction of this pianoforte was encouraged in Paris by Duke Christian IV. This instrument would therefore be an early work, since, from 1770, Mercken only manufactured square pianos in the English style.

That he later changed his style of instrument to suit the Parisian market is not surprising, and there are many examples at that time of migrant makers adopting the style of their adopted country, such as Zumpe in London and Taskin in Paris.

In addition, this piano was an opportunity to experiment for our maker. Musically, it is notable in offering an exceptionally large musical range for the time, up to a high G. These experiments suggest that the instrument was made early in his career, at a time when Mercken was looking for ways to produce the ideal instrument.

This harpsichord-shaped pianoforte by Mercken is also unique for incorporating two types of piano mechanisms: in the bass half, a release mechanism similar to those of the Silbermanns, and in the treble half, a mechanism without release of the Prellmechanik type. The latter operates with the use of solid heads, “instead of the cardboard rolls” found in the bass half, allowing “better sound production of the high notes”. According to Christopher Clarke, this mechanism was probably fitted by Mercken to replace the Silbermann mechanism that was there previously. A comb, compatible with the hammer-heads of a Silbermann-type mechanism, is visible but obsolete. Mercken probably first made this system around 1768, before modifying it, probably to appease the critics of the time who deemed this type of release mechanism too heavy, slow and tiring to play. Indeed, in 1767, one could read in the press:

For some time now hammer-head harpsichords, called fortepianos, have been brought to Paris, very artistically worked in Strasbourg by the famous Silbermann. These harpsichords […] are very pleasant to listen to, […] but they are more difficult to play, because of the weight of the hammer-head, which tires the fingers, & which even makes the hand heavy over time.

“Facteur de Clavecins” written by M. du Moutier for the “Dictionnaire portatif des Arts et Metiers” published in Amsterdam in 1767

Therefore, this type of criticism may have led Mercken to modify the treble mechanism in order to offer a piano adapted to French tastes, allowing lighter and faster play. According to Christopher Clarke, these modifications could have been carried out before the instrument left the workshop and it is without doubt the work of Mercken:

The Prell-leiste is made from the same rather unusually-figured pearwood as was used for parts of the keyframe and the treble hammer-heads are worked in a similar manner to the saddles that receive the cardboard rolls of the bass hammer-heads.

A grand piano by J. K. Mercken, Paris c.1768: context and comparison with instruments by G. & J-H. Silbermann and C. Baumann

These observations, as well as the beautifully calligraphed signature probably made by a professional, allow us to dismiss the idea that Mercken would have modified a piano made by another maker. In any case, this piano features a split mechanism that is both rare and surprising, which again seems to create a connection with Christian Baumann, since the only other known piano with distinct mechanisms for the bass and treble sides is a square model by Baumann, dated circa 1790[1].

[1] Christopher Clarke, Analysis of a harpsichord-shaped piano by Mercken, November 2021. The piano by Baumann belongs to the Pooya Radbon Collection in Germany. This collection also contains a square piano by Mercken, dated 1785

The discovery of this new instrument by Jean-Kilien Mercken is of great importance for the history of French piano making. It also sheds light on a previously unknown aspect of the production of Mercken – the first Parisian maker of pianofortes – since no harpsichord or harpsichord-shaped piano was known to have been made by him until now. This instrument could therefore be the first French pianoforte. Vichy Enchères hopes to see you on Saturday 7 May 2022 for the sale of this historic instrument.