Provenant d’une importante collection européenne, un remarquable cistre de Gérard Joseph Deleplanque sera vendu à Vichy Enchères le 13 avril 2024. De belle facture, ce cistre a la particularité d’être le seul instrument connu de Deleplanque daté de 1784. Or, cette date à son importance, puisqu’il s’agit de l’année de mort du luthier. L’instrument serait donc le dernier modèle connu à avoir été réalisé avec certitude par Deleplanque, alors au sommet de son art.

Découvrez cet ultime cistre qui, à l’aube de la disparition du mythique luthier lillois, allait aussi sonner le glas de l’instrument…

Gérard Joseph Deleplanque est le luthier lillois du XVIIIème siècle par excellence. De sa naissance en 1723, à sa mort en 1784, il demeure en effet toute sa vie à Lille. Né dans la paroisse Saint Etienne, on ne connaît malheureusement que peu de choses sur sa vie. Sa famille était originaire de Roubaix et son père, François Deleplanque, était musicien et marchand grossiste. En 1736, alors âgé de 12 ans, il commence un apprentissage de sculpteur auprès de Pierre Antoine Fremin et devient apprenti de la corporation des sculpteurs de Lille. En 1742, il présente son chef-d’œuvre, obtenant ainsi le statut de maître-artisan à l’âge de 19 ans. Compte tenu de l’absence de corporation de facteurs d’instruments, Deleplanque restera toute sa vie un membre actif de la corporation des tailleurs d’image, qui regroupait une variété de sculpteurs sur bois et sur pierre.

Le 27 avril 1745, il épouse Marie Caroline Joseph Lambelin, avec qui il aura six enfants, mais dont seuls Marie Marguerite Joseph et Amable François Joseph survivront. Ce dernier se fera connaître en tant que professeur de harpe et compositeur à Paris.

A partir de 1758, les archives qualifient Gérard Deleplanque de “faiseur d’instruments”, “luthier” ou encore de “maître luthier”, et ce jusqu’à sa mort. En réalité, il pourrait avoir été luthier bien avant 1758, puisqu’il est le témoin de mariage du luthier Maximilien Delannoy, en 1750.

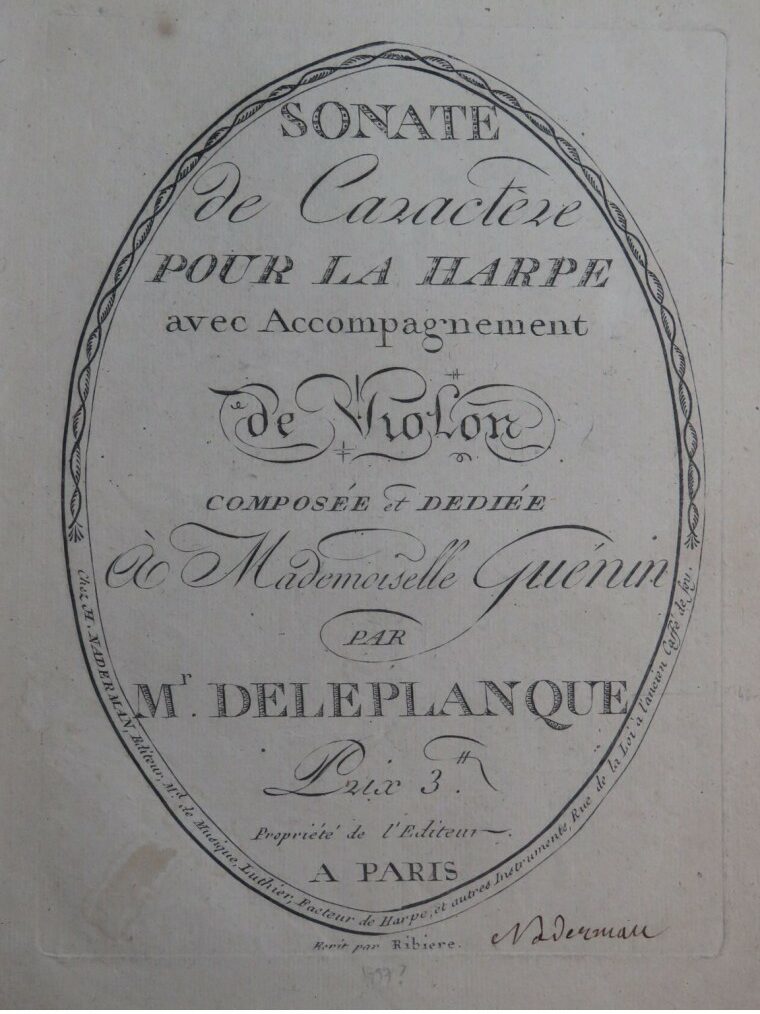

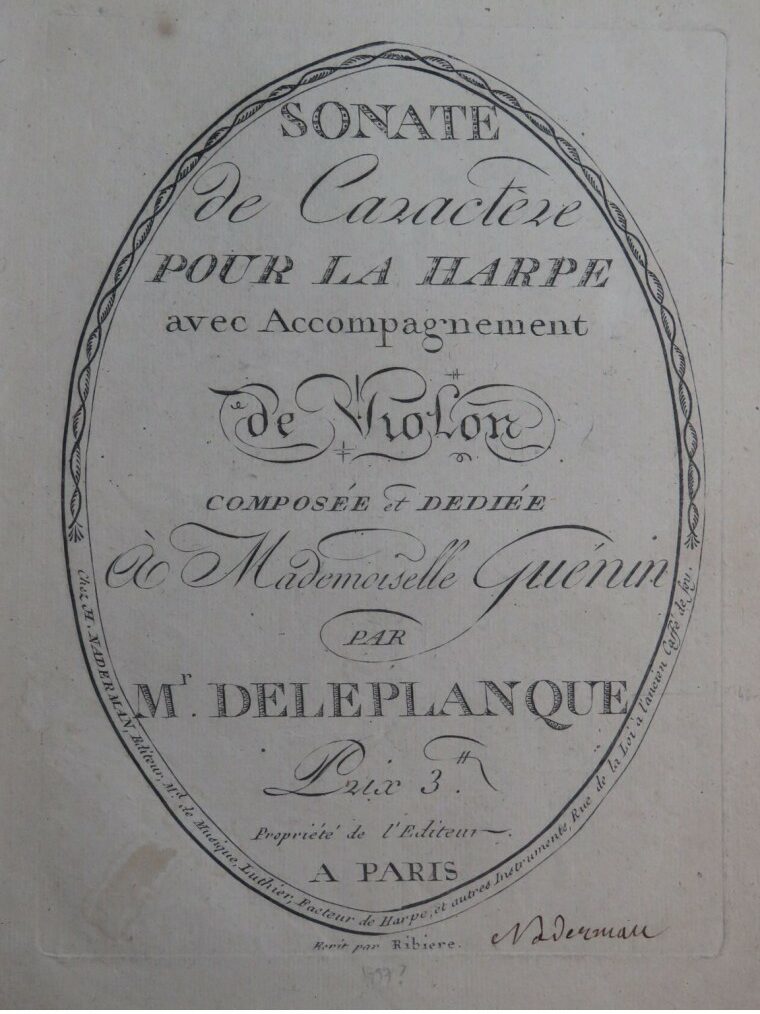

Comme il était fréquent au XVIIIe siècle, Deleplanque cumulait les activités et diverses archives nous renseignent sur son statut de marchand grossiste, entre 1746 et 1756. Le nom de Deleplanque est également mentionné sur les couvertures de livres de musique, laissant supposer qu’une partie de son activité consistait à distribuer des partitions. Notons enfin que son acte de décès le décrit en tant que “marchand luthier et maître sculpteur”[1].

[1] Informations biographiques provenant de Christine Hemmy, Philippe Bruguière, Jean-Philippe Echard, “New Insights into the Life and Instruments of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, Maker in Eighteenth-Century Lille”

Galpin Society Journal, n°71, march 2018

Les archives nous permettent de situer l’atelier de Deleplanque au “Marché aux Poulets, près le marché aux poissons” (dit aussi Marché aux Entes) de 1758 à 1766-1768, puis à la “Grande Chaussée, au coin de celle des Dominicains” environ de 1768 à 1776, et enfin sur la “Place de Ribour, près l’Hôtel de Ville”.

En 1767, sa fille Marie Marguerite épouse Pierre Joseph Peerens, horloger de métier. Chose intéressante, son acte de mariage précise qu’il est “horloger musicien”[1].

Peerens pourrait avoir rejoint l’atelier de Deleplanque peu après son mariage, apportant avec lui ses compétences d’horloger, utiles notamment pour la fabrication de mécaniques innovantes. Au décès de Deleplanque en 1784, à l’âge de 61 ans, Peerens assiste la veuve du luthier, Marie Caroline, dans la reprise de l’atelier puis, à la mort de celle-ci survenue autour de 1788-89, il poursuit la production jusqu’à sa propre disparition en 1819. En revanche, l’absence de stock de bois semble indiquer que durant cette époque, Peerens ne fabriquait plus d’instruments lui-même, ce qui pourrait expliquer le peu d’instruments connus de la période “Peerens-Deleplanque”.

[1] Christine Hemmy, Philippe Bruguière, Jean-Philippe Echard, “New Insights into the Life and Instruments of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, Maker in Eighteenth-Century Lille”. Galpin Society Journal, n°71, march 2018

L’étude réalisée sur le luthier et publiée en 2018 dans le Galpin Society Journal[1] a permis d’établir un premier corpus d’instruments fabriqués par l’atelier Deleplanque, comptant plus d’une soixantaine de modèles. En comparaison avec les autres luthiers de province connus au XVIIIème siècle, la production de Deleplanque était très importante. L’inventaire des oeuvres de Deleplanque a également permis de distinguer les différences entre les instruments fabriqués par Gérard Joseph Deleplanque de 1758 à 1784, de ceux de l’atelier Deleplanque dirigé par sa veuve et son gendre Peerens de 1784 à 1789, et ceux de Pierre Joseph Peerens de 1789 à 1819. L’instrument le plus ancien que nous connaissons est une guitare de 1761, conservée au Musée de Bruxelles (MIM). Cette dernière porte l’étiquette “Gérard Joseph DELEPLANQUE Luthier au Marché aux poulets à Lille. 1761”.

[1] Christine Hemmy, Philippe Bruguière, Jean-Philippe Echard, “New Insights into the Life and Instruments of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, Maker in Eighteenth-Century Lille”. Galpin Society Journal, n°71, march 2018

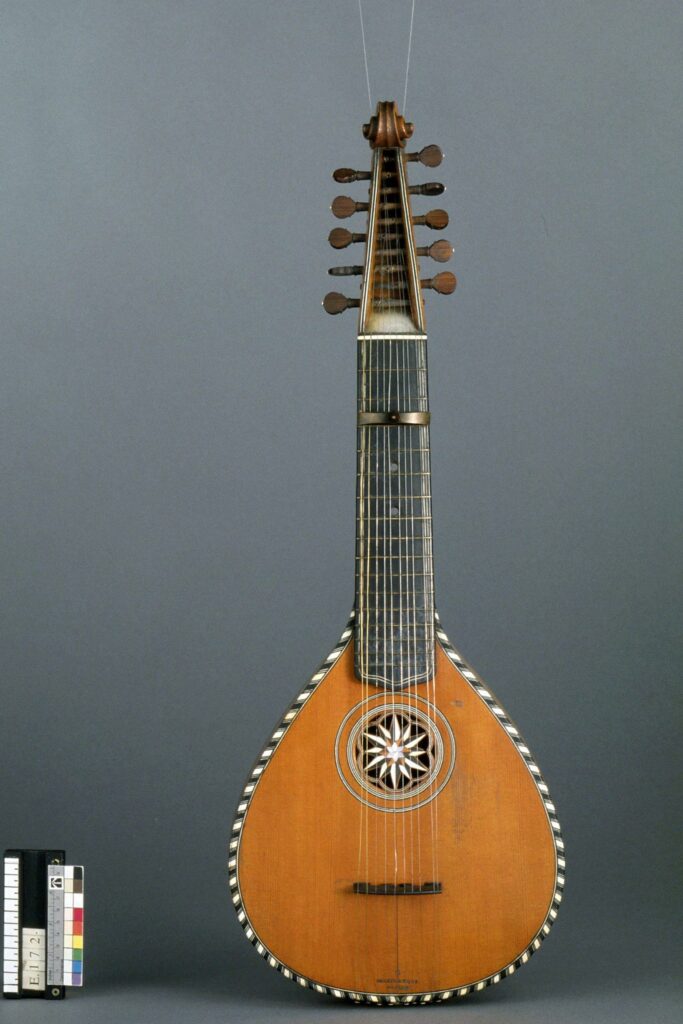

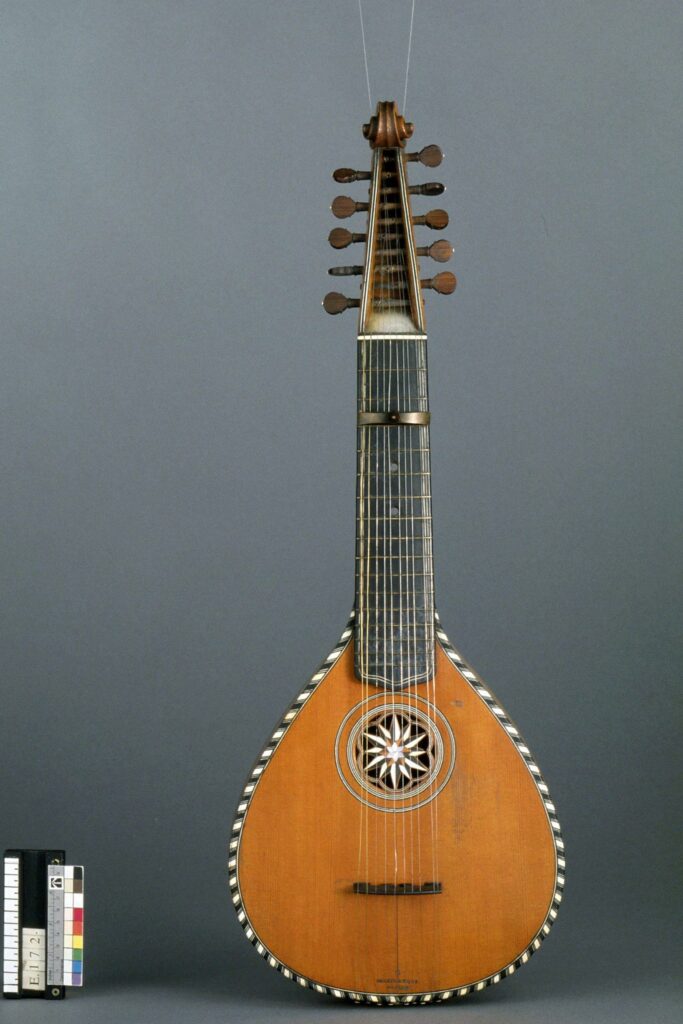

La majorité des instruments connus de Deleplanque sont des instruments à cordes pincées, notamment des cistres, très en vogue à l’époque. Parmi ces instruments, deux modèles réalisés en 1764 sont particulièrement intéressants car ils présentent une caisse en bateau – c’est-à-dire une table plus large que le dos – et témoignent de l’esprit créatif de Deleplanque.

Les cistres, qui représentent la majorité des instruments retrouvés, ont généralement 11 cordes métalliques, bien que certains en aient 10 ou 12. Leur forme varie, avec des corps en forme d’amande ou de luth, à dos plat ou bombé. L’étude minutieuse réalisée en 2018 sur les instruments de Deleplanque a en effet révélé une grande diversité de formes et de dimensions. Cette diversité suggère que Deleplanque n’a pas suivi de modèle standardisé pour fabriquer ses instruments, préférant sans doute une approche plus personnelle et adaptée à chaque pièce. L’examen des chevilliers a également offert un aperçu intéressant de l’évolution des techniques puisque, après l’arrivée de Peerens en 1769, presque tous les cistres semblent équipés d’un mécanisme à clé en laiton remplaçant les traditionnelles chevilles en bois, comme on peut l’observer sur le cistre de la vente Vichy Enchères d’avril 2024. Il est possible que Peerens, horloger de formation, ait joué un rôle significatif dans l’adoption de ce mécanisme semblable à celui des clés de montre. Les plus anciens exemples de ce genre se trouvent en Angleterre, autour des années 1750, et sont justement le fruit d’une collaboration entre un facteur d’instrument et un horloger (Reinerus Liessem et John Basire)[1].

[1] Panagiotis Poulopoulos, Aspects of Technology in Populuxe Musical Instruments of the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries, Deutsches Museum Verlag, 2022

L’atelier de Deleplanque a connu une période de forte production entre le milieu des années 1760 et le début des années 1780, en lien avec le goût pour les cistres anglais et instruments élaborés, tels que les guitares. Installé alors rue de la Grande Chaussée à Lille, au cœur du quartier des affaires, l’atelier proposait une vaste gamme de cistres sophistiqués.

En revanche, après le décès de Deleplanque, plus que quelques cistres semblent avoir été produits par Peerens, tous fabriqués dans les années 1790. En tout, une trentaine de cistres provenant de l’atelier Deleplanque ont été identifiés, majoritairement fabriqués entre 1764 et 1790, période correspondant à la popularité de cet instrument en Europe.

Ce cistre a été réalisé en 1784, l’année de la mort de Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, certainement pour répondre à une commande, comme c’était le cas de ses instruments les plus sophistiqués.

Il fait partie des 44 instruments inventoriés comme étant de la main de Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, sur près de 70 modèles identifiés sortant de son atelier[1]. Il est le seul connu daté de 1784, et le dernier à porter une étiquette datée, avant un cistre de 1790 inscrit “PEERENS – DELEPLANQUE / Marchand Luthier, au coin de / la rue de la Grande-Chaussée, / à Lille, 1790 [90 ms]”.

En effet, après la mort de Gérard Joseph Deleplanque en 1784, l’atelier est repris par sa veuve puis par son genre Peerens jusqu’en 1819, comme l’indique l’étiquette de l’instrument de 1790, ce qui explique l’existence d’instruments postérieurs à 1784. Toutefois, ceux-là ne sont pas de la main de Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, à la différence du cistre de la vente Vichy Enchères du 13 avril 2024. L’étiquette de ce dernier est similaire à celles que l’on retrouve dans trois instruments réalisés à la même époque, en 1782 et 1783. Ces étiquettes sont inscrites, à l’image de celle du cistre de 1784, “Gérard J. Deleplanque / Luthier, Rue de la Grande / Chauffée, coin de celle des / Dominicains, à Lille 178[4]”. En caractères d’imprimerie, seul le dernier chiffre de l’année est écrit à la main à l’encre. Ce type d’étiquette présente également une frise en bordure, composée de fleurs à huit pétales apparaissant par intervalle le long d’une rangée de trois lignes, elle-même ponctuée d’arabesques dans les angles[2].

[1] Christine Hemmy, Philippe Bruguière, Jean-Philippe Echard, “New Insights into the Life and Instruments of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, Maker in Eighteenth-Century Lille”. Galpin Society Journal, n°71, march 2018

[2] Christine Hemmy, Philippe Bruguière, Jean-Philippe Echard, “New Insights into the Life and Instruments of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, Maker in Eighteenth-Century Lille”. Galpin Society Journal, n°71, march 2018

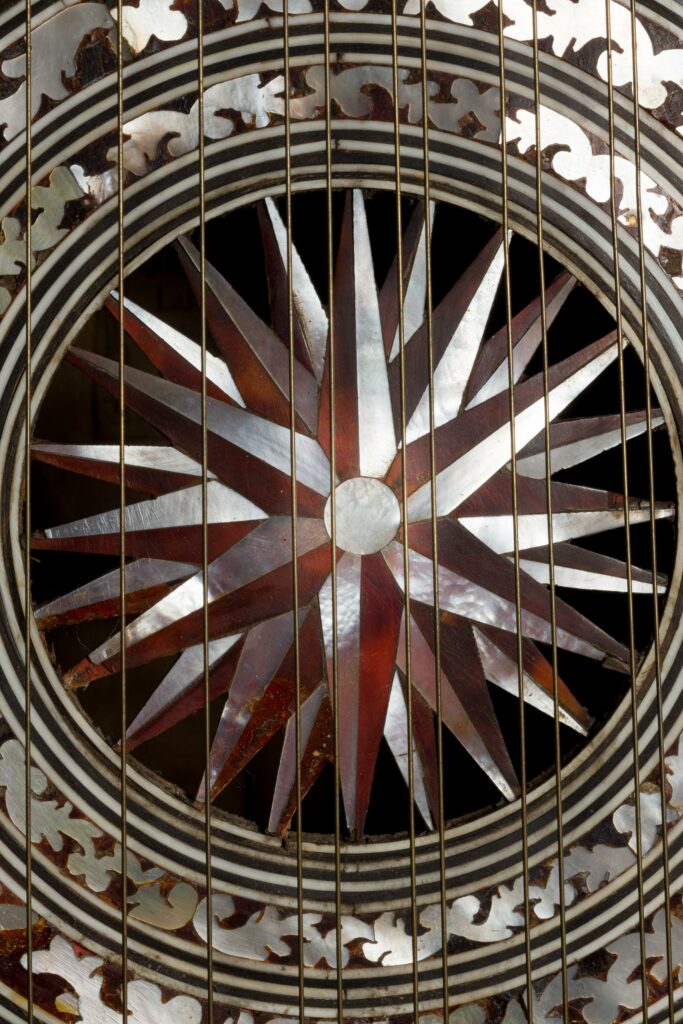

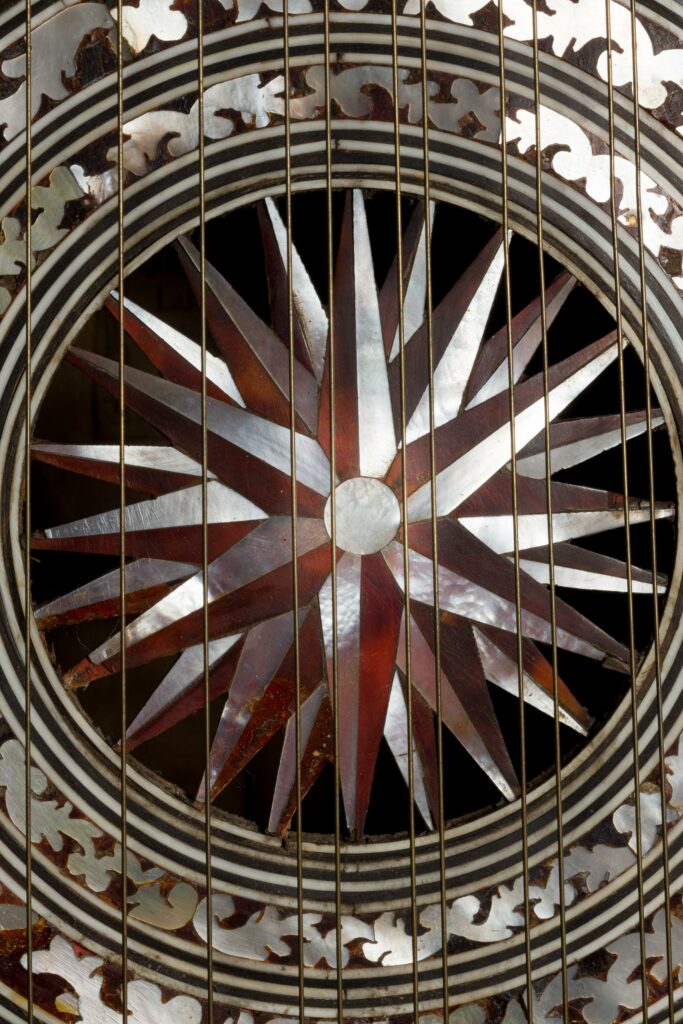

Comme souligné dans l’article de fond sur Deleplanque, la qualité décorative et la sophistication de ses instruments semblent avoir augmenté tout au long de sa carrière, en témoigne l’utilisation de plus en plus complexe de la nacre et de l’écaille, ainsi que l’élaboration de roses extrêmement raffinées à l’image de celle de ce cistre de 1784. Le fond et les éclisses sont ornés de filets en ébène et en ivoire. La table d’harmonie, la rosace et la touche sont incrustées de motifs en nacre et écaille et entourées de filets en ébène et ivoire.

Deux médaillons en nacre sont incrustés sur la tête, l’un étant monogrammé. Ce monogramme pourrait être celui de Gérard Joseph Deleplanque puisqu’il comporte un “D” et figure des têtes d’instruments variés, faisant probablement référence à son atelier. Ce monogramme est, à notre connaissance, unique, puisqu’on ne le retrouve sur aucun autre instrument connu du luthier.

Le cistre, qui était tombé en désuétude au milieu du XVIIème siècle, connaît un regain de popularité vers 1770. L’engouement est particulièrement marqué en Angleterre, comme en témoigne l’iconographie picturale de l’époque. Gérard Joseph Deleplanque se distingue comme l’un des principaux fabricants de cistres et consacre, à cette époque, les deux tiers de sa production à la réalisation de ce type d’instrument. Il fabrique alors parmi ses plus beaux modèles, à l’exemple du cistre de 1777 de la vente Vichy Enchères du 1er mai 2021.

La localisation de son atelier à Lille, capitale des Flandres alors très prospère, a sans doute facilité son commerce avec l’étranger, dont l’Angleterre.

Bien que les archives révèlent la présence de nombreux luthiers à Lille contemporains à Deleplanque, tels que Delannoy, Le Riche ou Le Blond, peu d’instruments de ces artisans sont connus aujourd’hui, à la différence des modèles de Deleplanque qui furent davantage préservés. Comment expliquer cela ? Il se peut que leur aspect décoratif très prononcé ait participé à une tendance plus naturelle à vouloir les protéger. Cela traduit aussi la grande renommée dont jouissait le luthier, puisque cette renommée assura une protection aux instruments jugés dignes de valeur marchande et artistique.

Dès 1780, on observe que les cistres deviennent minoritaires dans la production de Deleplanque, ce dernier ayant certainement senti que l’instrument allait être mis de côté au profit de la guitare. Le cistre de 1784 de la vente Vichy Enchères du 13 avril 2024 est donc l’un des derniers cistres – si ce n’est l’ultime – fabriqués par le luthier à l’aube de sa disparition…et de celle de l’instrument.

Toute l’équipe de Vichy Enchères vous donne rendez-vous le 13 avril 2024 pour la vente de ce dernier cistre de Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, préfigurant la fin du règne fulgurant de ce gracieux instrument…

A remarkable cittern by Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, originating from an important European collection, will be sold at Vichy Enchères on 13 April 2024. This beautifully crafted instrument is notable for being the only known instrument by Deleplanque dated 1784. It is an important year for this maker, as it is that of his death. This cittern could therefore be the last known instrument made by Deleplanque, who was then at the peak of his art. We invite you to discover this late cittern which was made at the dawn of the disappearance of the legendary maker from Lille, and whose advent would more generally coincide with the fall into disuse of the instrument itself.

Gérard Joseph Deleplanque was the 18th century maker from Lille par excellence. From his birth in 1723 to his death in 1784, he never left his city. He was born in the parish of Saint Etienne, and unfortunately little is known about his life. His family was from Roubaix and his father, François Deleplanque, was a musician and wholesale merchant. In 1736, then aged 12, he began an apprenticeship as a sculptor with Pierre Antoine Fremin and became an apprentice to the corporation of sculptors of Lille. In 1742, he submitted his masterpiece, obtaining the status of master craftsman at the age of 19. In the absence of a corporation of instrument makers, Deleplanque remained, throughout his life, an active member of the corporation of “image carvers”, which brought together a variety of wood and stone carvers.

On 27 April 1745, he married Marie Caroline Joseph Lambelin, with whom he had six children, but only Marie Marguerite Joseph and Amable François Joseph survived. The latter became known as a harp teacher and composer in Paris.

From 1758, historical archives describe Gérard Deleplanque as an “instrument maker”, “luthier” or sometimes “master violin maker”, and this until his death. In reality, he could have been a violin maker well before 1758, as suggested by the fact that he was the best man at the wedding of violin maker Maximilien Delannoy in 1750.

As was common in the 18th century, Deleplanque had a portfolio of activities and several historical documents inform us of his profession as a wholesale merchant between 1746 and 1756. The name Deleplanque also features on the covers of music books, suggesting that part of his activity consisted of distributing sheet music. Finally, it is worth noting that his death certificate describes him as an “instrument maker and merchant and master carver”[1].

[1] Informations biographiques provenant de Christine Hemmy, Philippe Bruguière, Jean-Philippe Echard, “New Insights into the Life and Instruments of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, Maker in Eighteenth-Century Lille”

Galpin Society Journal, n°71, march 2018

Historical archives allow us to locate Deleplanque’s workshop at the “Marché aux Poulets, near the fish market” (also known as Marché aux Entes) from 1758 to 1766-1768, then at the “Grande Chaussée, at the corner of that of the Dominicans” approximately from 1768 to 1776, and finally on the “Place de Ribour, near the Hôtel de Ville”..

In 1767, his daughter Marie Marguerite married Pierre Joseph Peerens, a professional watchmaker. Interestingly enough, his marriage certificate indicates that he is a “musician watchmaker”[1].

Peerens may have joined Deleplanque’s workshop shortly after his marriage, bringing with him his skills as a watchmaker, useful in particular for the manufacture of innovative mechanics. When Deleplanque died in 1784, at the age of 61, Peerens assisted the maker’s widow, Marie Caroline, in taking over the workshop and then, when she died around 1788-89, he became sole proprietor until his death in 1819. However, the absence of a stock of wood seems to indicate that during this period, Peerens no longer manufactured instruments, which could explain why there are few instruments known from the “Peerens-Deleplanque” period.

[1] Christine Hemmy, Philippe Bruguière, Jean-Philippe Echard, “New Insights into the Life and Instruments of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, Maker in Eighteenth-Century Lille”. Galpin Society Journal, n°71, march 2018

The research carried out on the maker and published in 2018 in the Galpin Society Journal[1] made it possible to draw an initial list of instruments manufactured by the Deleplanque workshop, including more than 60 examples. In comparison with other provincial makers known in the 18th century, Deleplanque’s production was very significant. The examination of Deleplanque’s output also highlighted differences between the instruments manufactured by Gérard Joseph Deleplanque from 1758 to 1784, those of the Deleplanque workshop run by his widow and his son-in-law Peerens from 1784 to 1789, and those of Pierre Joseph Peerens from 1789 to 1819. The oldest instrument we know is a guitar from 1761, kept at the Musee de Bruxelles (MIM). It bears the label “Gérard Joseph DELEPLANQUE Luthier au Marché aux poulets a Lille. 1761”.

[1] Christine Hemmy, Philippe Bruguière, Jean-Philippe Echard, “New Insights into the Life and Instruments of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, Maker in Eighteenth-Century Lille”. Galpin Society Journal, n°71, march 2018

The majority of known instruments by Deleplanque are plucked string instruments, in particular citterns, which very fashionable at the time. Amongst these instruments, two examples made in 1764 are particularly interesting because they have boat-shaped bodies – in other words, their front is wider than their back – and attest to the creative spirit of Deleplanque.

Citterns, which represent the majority of instruments known to this maker, generally have 11 metal strings, although some have 10 or 12. Their shape varies: they can have almond-shaped or lute-shaped bodies, and flat or rounded backs. The careful study of the instruments by Deleplanque, carried out in 2018, revealed a great diversity of shapes and dimensions. This diversity suggests that Deleplanque did not follow a standardized model to manufacture his instruments, preferring a more tailored approach for each piece. The examination of the headstocks also provided an interesting insight into their technical evolution since, after the arrival of Peerens in 1769, almost all the citterns appear to have been fitted with a brass key mechanism replacing the traditional wooden pegs, as can be observed on the cittern from the Vichy Enchères sale in April 2024. It is possible that Peerens, a trained watchmaker, played a significant role in the adoption of this mechanism, similar to that of watch keys. The oldest examples of this kind of mechanism are found in England, around the 1750s, and are the result of a collaboration between an instrument maker and a watchmaker (Reinerus Liessem and John Basire) [1].

[1] Panagiotis Poulopoulos, Aspects of Technology in Populuxe Musical Instruments of the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries, Deutsches Museum Verlag, 2022

Deleplanque’s workshop experienced a period of high demand between the mid-1760s and early 1780s, following the fashion for English citterns and elaborate instruments, such as guitars. His workshop, which was established at the time on rue de la Grande Chaussée in Lille, in the heart of the business district, offered a wide range of elaborate citterns.

On the other hand, after Deleplanque’s death, only a few citterns appear to have been produced by Peerens, and they were all made in the 1790s. In total, around 30 citterns from the Deleplanque workshop have been identified, mostly made between 1764 and 1790, which coincides with the period when this instrument was most popular in Europe.

This cittern was made in 1784, the year Gérard Joseph Deleplanque died, most probably as a commission, as was the case with his most sophisticated instruments.

It is one of 44 instruments thought to have been made by Gérard Joseph Deleplanque himself, out of nearly 70 examples known to have been produced in his workshop[1]. It is the only one we know that is dated 1784, and the last instrument to bear a dated label, until a cittern from 1790 labelled “PEERENS – DELEPLANQUE / Marchand Luthier, au coin de / la rue de la Grande-Chaussée, / a Lille, 1790 [90ms]”.

Indeed, after the death of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque in 1784, the workshop was taken over by his widow and then by his son-in-law Peerens until 1819, as indicated by the label of the instrument from 1790, which explains the existence of instruments made after 1784. However, these are not by the hand of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, unlike the cittern in the Vichy Enchères sale on 13 April 2024. Its label is similar to those found in three instruments made around the same time, in 1782 and 1783. As with our cittern of 1784, these labels read: “Gérard J. Deleplanque / Luthier, Rue de la Grande / Chauffée, coin of celle des Dominicains, a Lille 178[4]”, all in printed letters, except for the last digit of the year which is handwritten in ink. This type of label also features a decorative frieze around its edges, made up of flowers with eight petals appearing at regular interval along a row of three lines, itself punctuated with arabesques in the corners[2].

[1] Christine Hemmy, Philippe Bruguière, Jean-Philippe Echard, “New Insights into the Life and Instruments of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, Maker in Eighteenth-Century Lille”. Galpin Society Journal, n°71, march 2018

[2] Christine Hemmy, Philippe Bruguière, Jean-Philippe Echard, “New Insights into the Life and Instruments of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, Maker in Eighteenth-Century Lille”. Galpin Society Journal, n°71, march 2018

As highlighted in the in-depth article on Deleplanque, the quality of the decorations and the sophistication of his instruments seem to have increased as the years went by, as evidenced by the increasingly intricate use of mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell, as well as the creation of extremely refined roses like that of this cittern from 1784. The back and sides are decorated with ebony and ivory purfling. The front, rosette and fingerboard are inlaid with mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell patterns and surrounded by ebony and ivory purfling.

Two mother-of-pearl medallions are inlaid on the head, with one featuring a monogram. This monogram could be that of Gérard Joseph Deleplanque since it includes a “D” and represents the heads of various instruments, probably a reference to his workshop. This monogram is, to our knowledge, unique, since it is not found on any other instrument known to this maker.

The cittern, which had fallen into disuse in the middle of the 17th century, experienced a resurgence in popularity around 1770. This was particularly true in England, as evidenced by the paintings of the time. Gérard Joseph Deleplanque was one of the main manufacturers of citterns, devoting, at that time, two thirds of his production to this type of instrument. It was then that he produced some of his most beautiful examples, such as the 1777 cittern in the Vichy Enchères sale on 1 May 2021. The location of his workshop in Lille, the then very prosperous capital of Flanders, undoubtedly facilitated his trade with foreign countries, including England.

Although historical archives reveal the existence of several makers in Lille who were contemporaries of Deleplanque, such as Delannoy, Le Riche or Le Blond, few instruments from these makers have survived, unlike those of Deleplanque which were better preserved. The explanation for this might lie in the fact that their very ornamented appearance encouraged their owners to more carefully preserve them. This could also stem from the great reputation this maker enjoyed, which ensured that instruments made by him were better protected due to their commercial and artistic value.

From 1780, the proportion of citterns in Deleplanque’s production started to decrease, the maker having likely anticipated that the instrument would soon be put aside in favour of the guitar. The 1784 cittern in the Vichy Enchères sale on 13 April 2024 is therefore one of the last – if not the last – cittern made by the maker at the dawn of his disappearance, and that of the instrument itself.

The entire Vichy Enchères team looks forward to seeing you on 13 April 2024 for the sale of this last cittern by Gérard Joseph Deleplanque, foreshadowing the end of the dazzling popularity of this graceful instrument.