Dès sa première époque, Fagnola s’attache particulièrement à perfectionner ses vernis, cherchant à obtenir un fini lumineux et transparent, ajoutant parfois quelques ornements aux instruments pour en parfaire l’esthétique. Durant les années 1920, la carrière de Fagnola connaît une ascension fulgurante et sa capacité à réinterpréter et à ajouter sa touche personnelle aux techniques des maîtres anciens lui permit d’affirmer son style. Cela en fait une figure emblématique de la lutherie du XXe siècle, perpétuant la grande tradition de l’école piémontaise.

Annibale Fagnola est né le 28 décembre 1866 à Montiglio, une petite ville située dans les collines du Monferrato, à cinquante kilomètres à l’est de Turin. Son acte de baptême constitue le premier document officiel le concernant. Son acte de naissance civil indique que la famille Fagnola vivait dans la Regione Convento et que son père, Domenico, était agriculteur.

Bien que la famille Fagnola ne figure pas parmi les plus anciennes de Montiglio, Giovanni Fagnola, le grand-père d’Annibale, y résidait bien avant 1850. La famille, d’origine probablement modeste, était composée de dix enfants – Annibale étant l’aîné. Ses études primaires furent probablement interrompues pour aider sa famille, ce qui explique son écriture parfois approximative.

Vers l’âge de vingt ans, Annibale Fagnola est actif en tant que boulanger à Montiglio, comme le fut Giuseppe Rocca dans les années 1820. En 1918, alors qu’il a déjà la cinquantaine, il se marie à Cattarina Risso à Turin, mais cette dernière décède l’année suivante, motivant Annibale Fagnola à retourner à Montiglio, où il travaille un temps avec Riccardo Genovese.

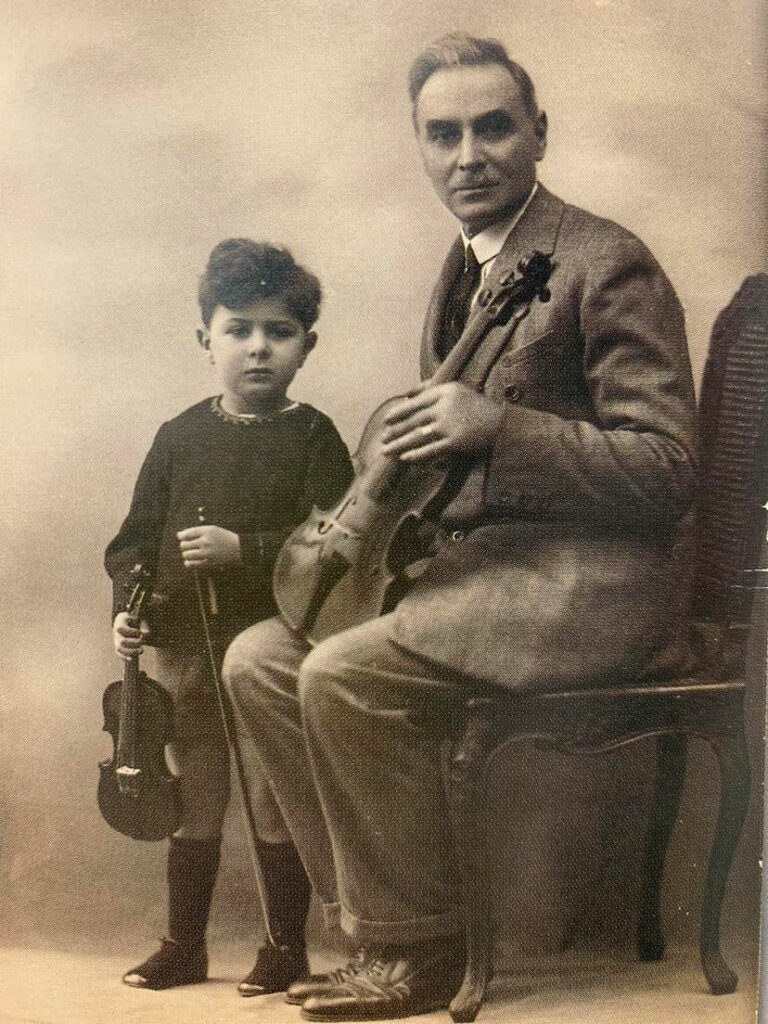

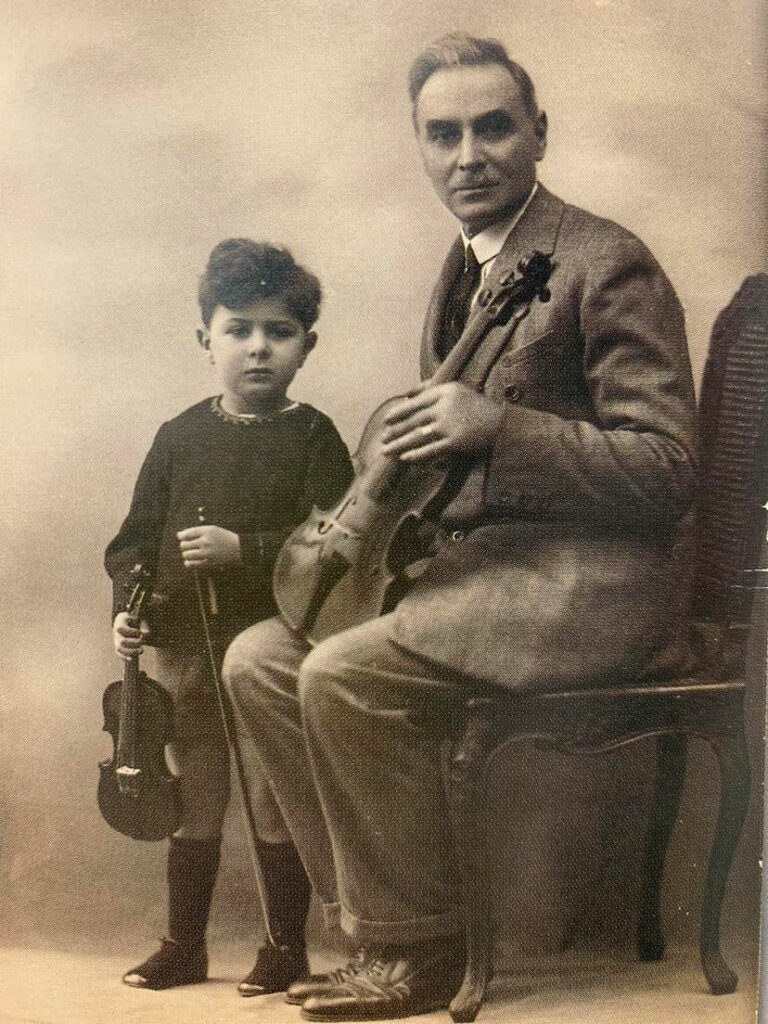

En 1921, il se remarie à Montiglio avec Elvira Danzena, qui lui donne un fils, Roberto, né la même année à Turin. Annibale portait beaucoup d’espoirs en ce fils unique puisqu’il espérait établir une lignée de luthiers. Certainement guidé par ce dessein, il lui fabrique dès son plus jeune âge des instruments, dont un petit violon ou encore un violoncelle. Malheureusement pour Annibale Fagnola, ce rêve de transmettre l’amour du métier à son fils ne s’est pas concrétisé.

Infos tirées de Giovanni Accornero, Ivan Epicoco, Eraldo Guerci, Liuteria Piemontese, Annibale Fagnola, Annibalotto Fagnola, Stefana Vittoria Fasciolo, Riccardo Genovese, 1999, edizioni I

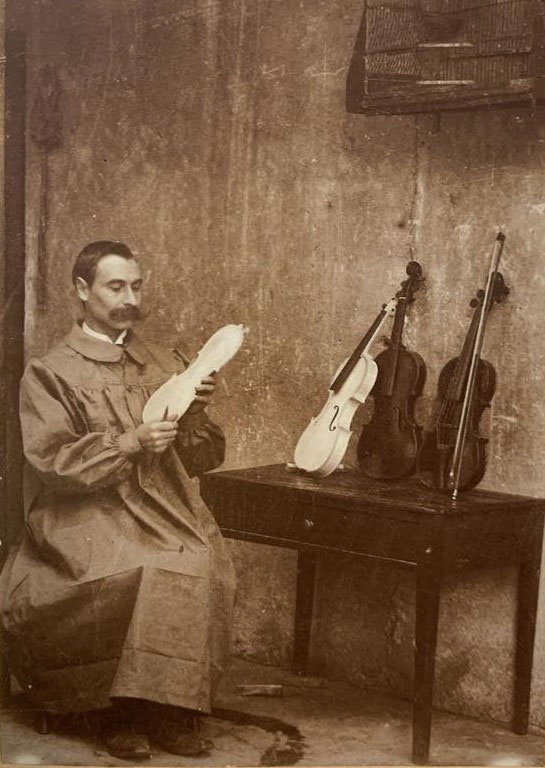

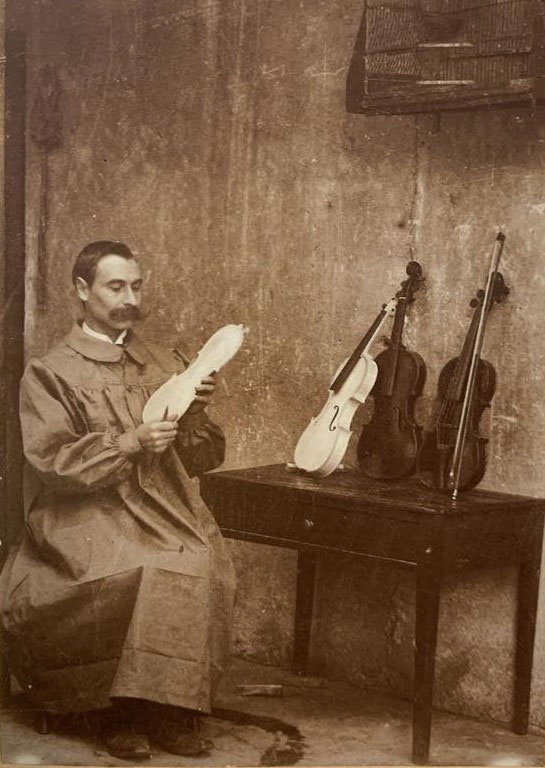

En 1894, à l’âge de vingt-sept ans, Fagnola déménage à Turin, intégrant rapidement le milieu de la lutherie. En effet, un an seulement après son installation à Turin, il se déclare « fabricant d’instruments de musique » et ouvrira probablement cette même année 1895 son premier atelier. Plusieurs hypothèses existent concernant son apprentissage. Les unes suggèrent une formation auprès de son père, les autres supposent qu’il aurait étudié avec Enrico Marchetti peu après son arrivée à Turin en 1894. Pourtant, tout laisse à croire qu’il était autodidacte. Son aptitude naturelle pour le travail du bois pourrait s’expliquer par sa jeunesse à Montiglio, où beaucoup d’artisans locaux travaillaient ce matériau et où la musique était présente. Au début de sa carrière, il se considérait davantage comme un “fabricant d’instruments” que comme un luthier à proprement parler. C’est au tournant du XIXe siècle, suite à son installation à Turin, qu’il va progressivement se perfectionner, et ce principalement grâce à l’avocat et collectionneur d’instruments Orazio Roggiero, qui lui permit d’accéder et d’étudier une riche collection d’instruments à cordes.

En 1899, Annibale Fagnola apparaît pour la première fois dans l’annuaire commercial majeur de Turin, le Paravia, sous le titre de « Constructeur d’instruments de musique ». Malgré une absence entre 1900 et 1902, il réapparaît en 1903 en tant que “luthier” et y sera par la suite constamment mentionné jusqu’à sa mort en 1939.

A partir de 1903, son activité prend un essor rapide et gagne en réputation. La demande s’intensifie alors et Fagnola embauche plusieurs assistants et élèves renommés. Des luthiers tels que Riccardo Genovese et Stefano Vittorio Fasciolo vont travailler sous sa direction, tout comme son propre neveu, Annibalotto Fagnola.

Toutefois, c’est avec Evasio Guerra qu’il va établir l’une de ses plus fructueuses collaborations. Celle-ci est aujourd’hui très perceptible sur certains de leurs modèles qui présentent de nombreuses similitudes. A la mort d’Annibale Fagnola le 16 octobre 1939 à Turin, son atelier et ses outils sont légués à Annibalotto. Malgré l’importance qu’eut son atelier, celui-ci cessa d’exister après 1945. Son fils, Roberto, ne souhaitait pas faire carrière dans la lutherie et Annibalotto était trop inexpérimenté pour en reprendre la direction. En ce qui concerne ses élèves, tels que Riccardo Genovese et Stefano Fasciolo, ils décédèrent respectivement en 1935 et 1944.

C’est en 1906 qu’Annibale Fagnola reçoit ses premières distinctions, à l’occasion des expositions de Gênes et de Milan, au cours desquelles il remporte des diplômes et médailles. Plus que celle de Gênes, l’Exposition Internationale de Milan est un véritable succès pour Fagnola qui parvient à vendre tous les violons exposés. Peu de temps après, il étend son activité et déménage son atelier Via San Tommaso. Cependant, c’est réellement en 1911, à l’Exposition Universelle de Turin, que le travail de Fagnola est couronné de succès. En effet, à l’occasion du 50ème anniversaire de l’unification italienne, Fagnola est récompensé de la médaille d’or – affirmant sa place parmi les maîtres luthiers internationaux. Suite à cette consécration, les commandes d’instruments grimperont en flèche. Fagnola était particulièrement apprécié en Angleterre et jouissait d’une très bonne réputation dès le début de sa carrière. Il travailla là-bas en collaboration avec plusieurs grandes maisons à l’instar de W. E. Hill and Sons ou J. and A. Beare.

Alors qu’il rentre dans la quarantaine, Annibale Fagnola s’engage dans la lutherie. Les années 1905-1910 peuvent ainsi être qualifiées de “période de jeunesse” ou de “première époque”. Au début de sa carrière, il est très proche d’Orazio Roggiero qui lui permet d’observer et d’étudier les instruments de maîtres anciens, qu’il commence à imiter. Probablement autodidacte, le luthier apprend par tâtonnements, en faisant des essais et des erreurs, ce qui est parfois perceptible dans la simplicité de certaines de ses premières œuvres.

Néanmoins, grâce à un talent inné et à l’expérience acquise, Fagnola se perfectionne rapidement et dès le début de sa production, ses oeuvres sont reconnues par ses pairs et les experts. L’Exposition Universelle de 1911 de Turin en est un bon exemple puisqu’elle a vu la consécration des instruments de Fagnola et l’affirmation de son identité stylistique, mélangeant modèle personnel et références aux luthiers de Turin – principalement Pressenda, Rocca et Guadagnini. Dès sa première époque, Fagnola s’attache particulièrement à perfectionner ses vernis, cherchant à obtenir un fini lumineux et transparent, ajoutant parfois quelques ornements aux instruments pour en parfaire l’esthétique.

Durant les années 1920, la carrière de Fagnola connaît une ascension fulgurante et, pour répondre à la demande croissante d’instruments à l’international, le luthier s’appuie sur plusieurs collaborateurs, parmi lesquels on retrouve Riccardo Genovese et son neveu Annibalotto, ou encore Evasio Guerra. Significatif de l’estime dont jouissait Fagnola dans les années 20, le dictionnaire des luthiers anciens et modernes d’Henri Poidras en fait l’éloge suivante en 1929 :

“Sa renommée comme l’un des meilleurs luthiers de notre époque est quasi mondiale. Fils de ses œuvres, il ne se réclame d’aucun maître. Les modèles de Guadagnini et de Pressenda lui permirent, en les reproduisant souvent, de devenir le copiste distingué que l’on sait.”

Henri Poidras, Dictionnaire des luthiers anciens et modernes, critique et documentaire, tome additif (vol. II), 1929

La mention de “copiste” est ici intéressante, puisque Fagnola faisait précisément la distinction entre le fait de « copier » et d’ « imiter » un instrument. Pour lui, copier une œuvre permettait de conserver son propre style, tandis qu’imiter nécessitait de s’effacer derrière le maître pour garantir une fidélité minutieuse à l’original, et ce jusque dans les moindres détails, de telle sorte que certains des travaux d’imitation de Fagnola étaient si parfaits qu’il est aujourd’hui presque impossible de les discerner des originaux. Toutefois, bien qu’il puisse être tentant de vouloir étiqueter Fagnola d’imitateur, sa capacité à réinterpréter et à ajouter sa touche personnelle aux techniques des maîtres anciens lui permit d’affirmer son style. Cela en fait une figure emblématique de la lutherie du XXe siècle, perpétuant la grande tradition de l’école piémontaise.

“It would be unjust to consider Fagnola only as a copyist or imitator. Due to his skill in reinterpreting the technical and stylistic lessons of Guadagnini. Pressenda and Rocca without ever losing his own identity, Annibale Fagnola was the natural successor to the great tradition of the Piedmontese school, proving himself to be a fundamental figure in twentieth-century violin making.”

Giovanni Accornero, Ivan Epicoco, Eraldo Guerci, Liuteria Piemontese, Annibale Fagnola, Annibalotto Fagnola, Stefana Vittoria Fasciolo, Riccardo Genovese, 1999, edizioni Il Salabue

Dans les années 1930, Fagnola cherche constamment à s’améliorer et, malgré son succès en tant que luthier au style affirmé, consacre beaucoup de son temps à réaliser des copies fidèles. Fagnola menait principalement des recherches sur le vernis, visant à reproduire les originaux ou à leur donner un aspect vieilli. Cependant, certaines de ses dernières œuvres montrent les marques de l’âge et de la maladie qui l’a finalement emporté.

En 1931, il déménage son atelier pour la dernière fois. Les années 30 sont aussi marquées par son amitié avec le professeur Vincenzo Tommasini, une figure importante de la scène musicale de l’époque, avec qui il entretient une longue correspondance. Plusieurs lettres de Tommasini font l’éloge des instruments de Fagnola. Ainsi en 1937, il écrit :

“I have to tell you that your violin has such a good sound and I like it so much that I put away my old violins and only play on yours”

Giovanni Accornero, Ivan Epicoco, Eraldo Guerci, Liuteria Piemontese, Annibale Fagnola, Annibalotto Fagnola, Stefana Vittoria Fasciolo, Riccardo Genovese, 1999, edizioni Il Salabue

Very early on, Fagnola paid particular attention to the quality of his varnishes, seeking to obtain a luminous and transparent finish, and sometimes added a few ornaments to the instruments to further improve their visual appearance. During the 1920s, Fagnola’s career experienced a meteoric rise and his ability to re-interpret and add his personal touch to the work of the old masters allowed him to assert his own style. This makes him an emblematic figure of 20th century violin making, who perpetuated the great tradition of the Piedmontese school.

Annibale Fagnola was born on 28 December 1866 in Montiglio, a small town located in the Monferrato hills, 50km east of Turin. His baptism certificate is the first official document we have about him. His civil birth certificate indicates that the Fagnola family lived in the Regione Convento and that his father, Domenico, was a farmer.

Although the Fagnola family is not amongst the oldest in Montiglio, Giovanni Fagnola, Annibale’s grandfather, resided there well before 1850. The family, probably of modest origins, included 10 children, Annibale being the eldest. His primary school studies were most likely interrupted so he could help his family, which might explain his approximate use of the written language at times.

Around the age of 20, Annibale Fagnola was active as a baker in Montiglio, as was Giuseppe Rocca in the 1820s. In 1918, when he was already in his fifties, he married Cattarina Risso in Turin, but she died the following year, prompting Annibale Fagnola to return to Montiglio, where he worked for a time with Riccardo Genovese.

n 1921, he re-married in Montiglio with Elvira Danzena, who gave him a son, Roberto, born the same year in Turin. Annibale had high expectations for his only son, and hoped it would be the start of a dynasty of violin makers. With this in mind, he made instruments for his son when he was still very young, including a small violin and a cello. Unfortunately for Annibale Fagnola, his aspiration of passing on the love of the craft to his son did not materialise.

Information extracted from Giovanni Accornero, Ivan Epicoco, Eraldo Guerci, Liuteria Piemontese, Annibale Fagnola, Annibalotto

In 1894, at the age of 27, Fagnola moved to Turin, and quickly entered the world of violin making. Indeed, only one year after his move, he declared himself a “musical instrument maker” and probably opened his first workshop that same year, in 1895. Several theories exist as to his training. Some believe he might have trained with his father, while others think that he studied with Enrico Marchetti shortly after his arrival in Turin in 1894. However, all the evidence points to him having been self-taught. His natural talent for wood working could be explained by his early years in Montiglio, where many local artisans worked this material and music was present. At the start of his career, he considered himself an “instrument maker” rather than a violin maker specifically. It was at the turn of the 19th century, following his move to Turin, that he gradually specialised and perfected his craft, mainly thanks to the lawyer and instrument collector Orazio Roggiero, who gave him access to his great collection of stringed instruments.

In 1899, Annibale Fagnola appeared for the first time in Turin’s main business directory, Paravia, as « Musical Instrument Manufacturer ». He was not listed there between 1900 and 1902, but reappeared in 1903 as a “violin maker” and was included thereafter without interruption until his death in 1939.

From 1903, his activity grew rapidly and gained in reputation. Demand for his instruments intensified and Fagnola hired several renowned assistants and apprentices. Makers such as Riccardo Genovese and Stefano Vittorio Fasciolo worked under his wing, as would his nephew, Annibalotto Fagnola.

However, his most fruitful collaboration was with Evasio Guerra. This is very noticeable today when comparing some of their models, as they are very similar. When Annibale Fagnola died on 16 October 1939 in Turin, his workshop and tools were passed on to Annibalotto. Despite the workshop’s success, it closed its doors after 1945. His son Roberto did not want a career in violin making, and Annibalotto was too inexperienced to take over the running of the workshop. As for his pupils, Riccardo Genovese and Stefano Fasciolo, they died in 1935 and 1944 respectively.

Annibale Fagnola received his first awards in 1906, at the exhibitions in Genoa and Milan, in which he won diplomas and medals. The Milan International Exhibition was particularly successful for Fagnola, as he managed to sell all the violins he exhibited. Shortly afterwards, he expanded his business and moved his workshop to Via San Tommaso. However, it was really in 1911, at the Universal Exhibition in Turin, that Fagnola’s work was crowned with success. Indeed, in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of the Italian unification, Fagnola was awarded the gold medal – confirming his place amongst the best violin makers worldwide. Following this great success, the demand for his instruments skyrocketed. Fagnola was particularly appreciated in England, where he had a very good reputation from the start. He collaborated with several large establishments there, including W. E. Hill and Sons and J. and A. Beare.

Annibale Fagnola started his violin making career as he entered his forties. The period 1905-1910 can therefore be described as his first or early period. At the start of his career, he was very close to Orazio Roggiero, who allowed him to examine and study instruments by the old masters, which he began to imitate. As he was probably self-taught, he learned through trial and error, which is sometimes in evidence in the rudimentary nature of some of his early works.

Nevertheless, thanks to an innate talent and his growing experience, Fagnola improved quickly, and from the start, his instruments were praised by his peers and the experts. This was in evidence at the Universal Exhibition of 1911 in Turin, which saw Fagnola’s instruments rewarded for their individual style, which combined a personal model with elements from the makers of Turin – mainly Pressenda, Rocca and Guadagnini. Very early on, Fagnola paid particular attention to the quality of his varnishes, seeking to obtain a luminous and transparent finish, and sometimes added a few ornaments to the instruments to further improve their visual appearance.

During the 1920s, Fagnola’s career experienced a meteoric rise and, to meet the growing international demand for his instruments, he relied increasingly on assistance from several other makers, including Riccardo Genovese, his nephew Annibalotto and again Evasio Guerra. A good testimony of the esteem in which Fagnola was held in the 1920s can be found in Henri Poidras’s dictionary of ancient and modern violin makers, which praised him as follows in 1929:

“His reputation as one of the best makers of our time is almost universal. He is the son of his works, and claims no master. By often reproducing the models of Guadagnini and Pressenda, he became the distinguished copyist that we know.”

Henri Poidras, Dictionnaire des luthiers anciens et modernes, critique et documentaire, tome additif (vol. II), 1929

The mention of “copyist” here is interesting, since Fagnola made a clear distinction between “copying” and “imitating” an instrument. According to him, copying someone else’s work allowed one to maintain one’s own style, whilst imitating required one to step in the master’s shoes to meticulously reproduce the original, down to the smallest details, so much so that, today, some of Fagnola’s imitations are almost impossible to distinguish from the originals. Whilst it may be tempting to think of Fagnola as a pure imitator, his ability to re-interpret and add his personal touch to the work of the old masters allowed him to assert his own style. This makes him an emblematic figure of 20th century violin making, who perpetuated the great tradition of the Piedmontese school.

“It would be unfair to consider Fagnola as a mere copyist or imitator. Thanks to his ability to re-interpret the technical and stylistic learnings from Guadagnini, Pressenda and Rocca, without ever losing his own identity, Annibale Fagnola was the natural successor to the great tradition of the Piedmontese school, proving himself to be a key figure in 20th century violin making.”

Giovanni Accornero, Ivan Epicoco, Eraldo Guerci, Liuteria Piemontese, Annibale Fagnola, Annibalotto Fagnola, Stefana Vittoria Fasciolo, Riccardo Genovese, 1999, edizioni Il Salabue

In the 1930s, Fagnola constantly sought to improve and, despite his success as a maker of individual style, he devoted much of his time to making faithful reproductions. Fagnola mainly focused his research on varnish, aiming to reproduce that of the original instruments and give them an antique appearance. However, some of his later works betray the signs of age, and the illness from which he died eventually.

In 1931, he moved his workshop for the last time. The 1930s were also marked by his friendship with Professor Vincenzo Tommasini, an important figure on the musical scene of the time, with whom he corresponded for a while. Several letters from Tommasini praise Fagnola’s instruments. For instance, in 1937, he wrote:

“I have to tell you that your violin has such a good sound and I like it so much that I put away my old violins and only play on yours”

Giovanni Accornero, Ivan Epicoco, Eraldo Guerci, Liuteria Piemontese, Annibale Fagnola, Annibalotto Fagnola, Stefana Vittoria Fasciolo, Riccardo Genovese, 1999, edizioni Il Salabue