Le 6 juin 2024, à Vichy Enchères, un remarquable violoncelle de Francesco Rugeri sera présenté à la vente, un événement sur le marché. En effet, au cours du XXIème siècle, moins d’un tiers des instruments de Francesco Rugeri passés aux enchères étaient des violoncelles. Ces derniers, pourtant considérés comme le nec plus ultra de sa production, sont ainsi particulièrement rares. L’occasion pour nous de revenir sur l’histoire mystérieuse de ce luthier mythique, tantôt considéré comme l’élève d’Amati et le maître de Stradivari…

Francesco Rugeri – dit aussi Rugger, Ruggeri, Ruggieri – fait partie de ces figures majeures de l’histoire de la lutherie qui, malgré leur renommée, sont loin d’avoir livré tous leurs mystères. Les archives le concernant sont en effet relativement minces – ce qui n’a rien d’étonnant compte tenu de son existence au XVIIème siècle. On ne conserve ainsi que peu d’actes officiels, parmi lesquels son contrat de mariage, en date de 1652, avec Ippolita Ravasi (Crémone, paroisse San Bernardo) et son acte de décès, survenu le 28 octobre 1698 (paroisse San Trinita). Ces éléments permettent donc de situer approximativement sa naissance autour de 1620-1630.

Divers documents nous permettent également de savoir que Francesco Rugeri était surnommé « Il Per », en particulier les étiquettes de certains de ses instruments inscrites « Rugeri detto il Per » et plusieurs archives familiales autour de 1660. Il se pourrait que ce surnom ait été ajouté dans l’optique de se différencier d’autres luthiers, en particulier de la famille Rogeri de Brescia, active à la même époque et dont la production était parfois confondue avec celle de Francesco Rugeri.

Concernant son activité, on sait que Francesco Rugeri a travaillé au numéro 7 de la Contrada Coltellai, hors les murs de Crémone, dans la paroisse San Bernardo. On le retrouve à partir de 1687 dans la paroisse de San Sebastiano, à côté du couvent de San Sigismondo (Crémone). Il est assisté par ses trois fils, Giovanni Battista, Giacinto et Vincenzo, environ à partir de 1670.

Ses instruments étaient réputés pour leurs grandes qualités constructives et sonores, ainsi que pour leur raffinement. Ils passaient parfois pour des œuvres de Niccolò Amati. Une affaire judiciaire de 1685 rend d’ailleurs compte de la plainte du violoniste Tomaso Antonio Vitali auprès du duc de Modène, suite à son achat d’un violon prétendument d’Amati, s’avérant en réalité être de Rugeri. Cet exemple souligne la grande parenté de savoir-faire de ces deux mythiques luthiers.

Francesco Rugeri est traditionnellement considéré comme le premier élève de Niccolò Amati, bien que cet élément soit caution à débat, compte tenu de l’absence de trace de son apprentissage dans les documents de recensement de la maison Amati. Toutefois, il se pourrait que l’absence de document mentionnant le nom de « Rugeri » trouve son explication dans le fait que Francesco Rugeri ne résidait pas chez Amati durant son apprentissage, mais dans son logement personnel. Cela est d’autant plus vraisemblable que nous savons qu’il habitait en périphérie de Crémone. A titre de comparaison, le nom d’Antonio Stradivari, également considéré comme un élève d’Amati, n’apparaît pas non plus dans les archives de l’atelier. Concernant Francesco Rugeri, plusieurs autres indices tendent à penser qu’il aurait bel et bien été l’élève d’Amati. Comme évoqué, on constate une grande proximité stylistique entre certains instruments de Rugeri et ceux d’Amati, ce qui plaide en faveur d’une formation auprès de ce dernier[1]. La famille Rugeri habitait juste à l’extérieur de la ville de Crémone, dans les paroisses San Bernardo et San Sebastiano, et il est donc envisageable que cette localisation ait conduit Rugeri à se former chez Amati. Un petit violon de Niccolò et Girolamo Amati vendu à Vichy Enchères en 2021 tend à soutenir cette hypothèse, puisque celui-ci comportait justement une tête trahissant la main de Francesco Rugeri.

[1] Wurlitzer, W. Henry Hill, Arthur F. Hill and Alfred E. Hill ; with a new introduction by Sydney Beck and new supplementary indexes by Rembert (1963). Antonio Stradivari : his life and work, 1664–1737 (New Dover ed.). New York: Dover. pp. 27 and 31.

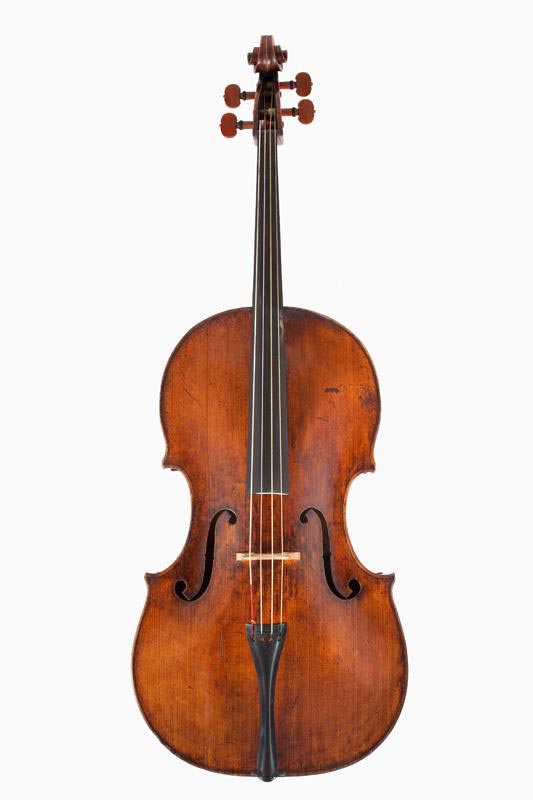

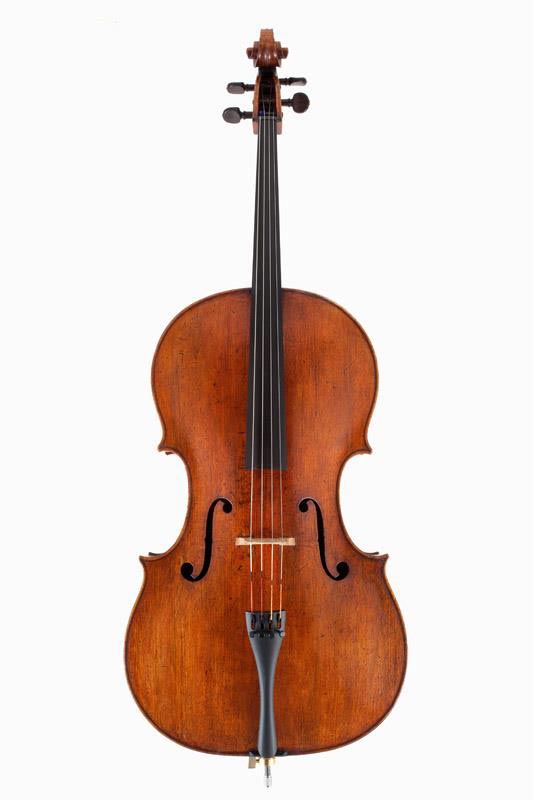

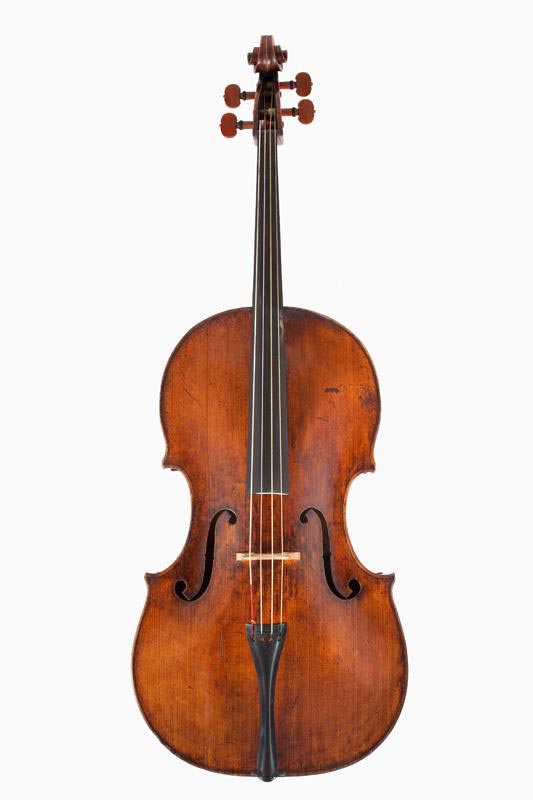

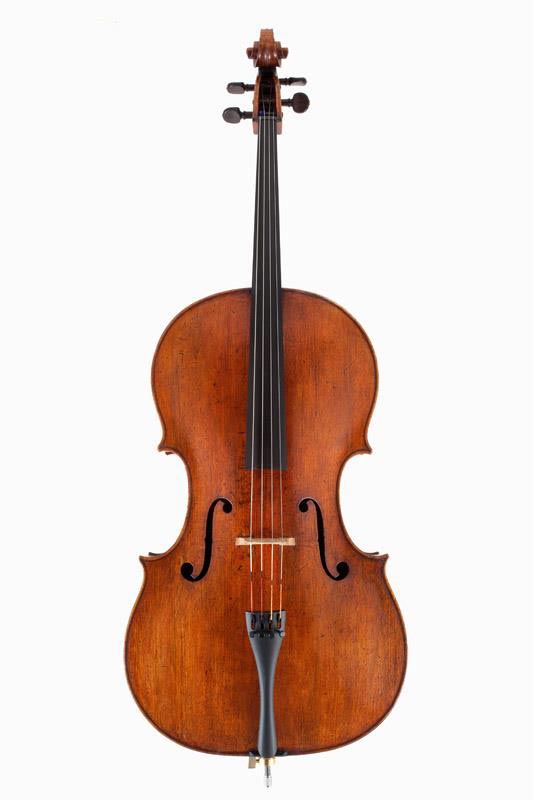

Réalisé vers 1680, le violoncelle de la vente du 6 juin 2024 suggère également une formation chez Amati.

“Rugger aurait été un élève d’Amati et certains détails de ce violoncelle rappellent effectivement le travail d’Amati, notamment en ce qui concerne le traitement des ouïes et de la tête.”

Interview de Jonathan Marolle, Vatelot-Rampal, Paris, luthier, spécialiste des instruments du quatuor à cordes, expert près la Cour d’Appel de Paris.

D’autre part, on conserve des instruments de Rugeri portant des étiquettes inscrites « Alumnus Nicolai Amati », à l’exemple d’un violon de 1663 étiqueté « Francescus Rugerius Alumnus Nicolai Amati fecit Cremonæ 1663 ». Rugeri se présentait ainsi lui-même comme un élève d’Amati. S’agissait-il d’une manière de se revendiquer de l’école d’Amati (lui permettant aussi de mieux vendre), ou d’un véritable fait historique ? La question subsiste.

Une chose est sûre, les familles Rugeri et Amati étaient très proches. Niccolò Amati était en effet le parrain de Giacinto, l’un des fils de Francesco Rugeri, baptisé en 1658. Trois décennies plus tard, en 1689, un petit-fils de Francesco Rugeri eut à son tour pour parrain Girolamo Amati II – alors à la tête de l’atelier familial depuis la mort de son père en 1684.

Parmi les grands mystères entourant la vie de Francesco Rugeri, l’un des plus intrigants est sans doute celui de ses liens avec Antonio Stradivari. Les récentes recherches tendent en effet à considérer qu’Antonio Stradivari aurait en réalité été formé par Francesco Rugeri, et non Niccolò Amati.

Comme il a déjà pu être évoqué, le nom de Stradivari n’apparaît nulle part dans les archives de l’atelier d’Amati – au même titre que celui de Rugeri. En outre, les instruments d’Antonio Stradivari divergent en bien des points de ceux d’Amati, alors que ses premiers modèles partagent des similitudes avec ceux de Francesco Rugeri.

La différence principale entre l’œuvre d’Amati et de Stradivari – sur laquelle s’appuie notamment les chercheurs défendant la thèse d’un apprentissage de Stradivari chez Rugeri -, s’observe sur les dos des instruments d’Amati, percés d’un petit trou en leur centre (utilisé pour graduer les dos). Or, cette technique est caractéristique du travail d’Amati et a été reprise par tous ses élèves connus, à l’exception d’Antonio Stradivari ou de Francesco Rugeri. Ce procédé étant absent de la production de Francesco Rugeri et, compte tenu de la proximité stylistique de ses instruments avec les premières œuvres de Stradivari, l’hypothèse selon laquelle Stradivari aurait été l’élève de Rugeri a donc été proposée. (La différence d’âge entre Rugeri et Stradivari rendant tout à fait plausible cette hypothèse.)

Bien qu’appartenant à l’école d’Amati, l’œuvre de Francesco Rugeri n’en est pas une copie, mais témoigne plutôt d’un esprit libre et novateur. Le luthier était notamment connu pour agrandir légèrement ses modèles et courber ses instruments. Ainsi, bien que ses modèles reprennent parfois des caractéristiques propres à l’art d’Amati, Rugeri les dépasse en mettant au point des techniques de construction uniques et des détails distinctifs rivalisant en qualité avec le savoir-faire d’Amati. Son travail est notamment caractérisé par une exécution délicate, particulièrement visible dans l’application habile et uniforme des vernis éclatants, aux teintes caractéristiques de Crémone, allant de l’orange foncé au jaune-orangé brillant – à l’exemple du violoncelle de la vente Vichy Enchères du 6 juin 2024.

Sa période la plus productive se situe dans les années 1670 et 1680, alors qu’il est assisté par ses trois fils. Son succès atteint son apogée après le déclin de Nicolò Amati et avant la montée en puissance de l’atelier d’Antonio Stradivari. Les instruments de Francesco Rugeri rencontrèrent très vite le succès et furent recherchés en raison de leur haut niveau d’exécution et de leur sonorité. Parmi les grands noms ayant possédé un instrument réalisé par Francesco Rugeri, on peut ainsi citer le comte Cozio di Salabue et le marquis Castiglioni. Cependant, peu de collections publiques conservent des instruments de Francesco Rugeri. On trouve seulement un violon et une basse de viole au Musée de la Musique de Paris (fin XVIIe et 1699) ; deux violoncelles à la Royal Academy of Music Museum (c.1689 et 1695, Londres) ; un violon au Muziekinstrumentenmuseum (1690, Bruxelles) et une viole d’amour au Scenkonstmuseet (1697, Stockholm).

Francesco Rugeri était réellement un inventeur de génie, comme le confirme la pérennité de certaines de ses créations. S’il a durablement marqué l’histoire de la lutherie, c’est principalement grâce à ses magnifiques violoncelles. Il en produisait deux types de tailles différentes, afin de s’adapter au registre musical. Les grands formats étaient davantage prisés pour le répertoire sacré, alors que les petits modèles servaient essentiellement à la musique profane. Le violoncelle de la vente Vichy Enchères du 6 juin 2024 offre un bel exemple du type dit de grande taille. Ses formes pleines et élégantes sont caractéristiques de la facture de Rugeri, et sont sublimées par un vernis délicat.

Ce violoncelle a été réalisé vers 1680 et est l’un des rares modèles parvenus jusqu’à nous. En effet, sur une trentaine d’instruments du maître passés aux enchères au XXIème siècle, moins d’un tiers étaient des violoncelles.

Rugeri est aussi particulièrement connu pour son invention d’un autre modèle, plus petit, devenu par la suite la norme pour l’instrument. Aujourd’hui encore, la taille des violoncelles imaginée par Francesco Rugeri reste en usage. A son époque, celle-ci était révolutionnaire puisqu’il fabriquait des instruments mesurant 10 centimètres de moins que ceux des autres luthiers crémonais. Cette taille réduite fut immédiatement appréciée par les musiciens, puisqu’elle leur permettait de gagner en mobilité et aisance.

Outre cet aspect formel, les violoncelles de Francesco Rugeri étaient réputés pour leur sonorité profonde et enveloppante.

L’œuvre de Francesco Rugeri marqua l’histoire de la lutherie et s’ancra durablement dans le temps grâce à sa qualité et aux innovations qu’elle proposait. Le savoir-faire élaboré par le maître fut aussi diffusé par la suite par ses trois fils luthiers et par ses élèves – dont peut-être Stradivari (voir plus haut).

Parmi les fils de Francesco Rugeri devenus luthiers, on compte d’abord l’aîné, Giovanni Battista Rugeri (1653 – 1711), qui travailla dans l’atelier de son père. Sa production reste peu connue et limitée. L’un de ses fils fut le neveu de Hieronymus Amati II – autre attestation des relations étroites qu’entretinrent ces deux familles.

Le deuxième fils de Francesco Rugeri, prénommé Giacinto (1661 – 1697. A distinguer du neveu de Niccolò Amati qui mourut en bas âge), travailla également dans l’atelier familial. Ses instruments sont, tout comme ceux de son frère, très rares. On sait qu’il eut un fils luthier, mais dont le travail est inconnu.

Enfin, Vincenzo Rugeri (1663 – 1719), le troisième fils de Francesco, était aussi actif dans l’atelier de ce dernier. Il est le plus connu et fut aussi renommé que son père. Il est parfois considéré comme le meilleur luthier de la famille, bien que ses instruments valent le plus souvent ceux de Francesco Rugeri. Vincenzo Rugeri marqua lui aussi l’histoire de la lutherie et aurait notamment été le premier professeur de Carlo Bergonzi.

Tous ont été formés par Francesco Rugeri, dans l’atelier familial, où ils réalisèrent des instruments pour lui ou avec lui. Après cette formation, autour des années 1690, les trois fils s’installèrent à Crémone, dans le voisinage d’Amati, Guarneri et Stradivari, perpétuant ainsi la tradition familiale…

Rendez-vous à Vichy Enchères le 6 juin 2024 pour la vente de ce rare violoncelle de Francesco Rugeri !

On 6 June 2024, a remarkable cello by Francesco Rugeri will be auctioned by Vichy Enchères. This is rare opportunity on the market; indeed, during the 21st century, less than a third of Francesco Rugeri’s instruments sold at auction were cellos. They are the most sought after instruments in his output, and also the rarest. On this occasion, let’s delve into the mysterious history of this legendary maker, believed by some to have been the student of Amati and the master of Stradivari.

Despite Francesco Rugeri’s – also known as Rugger, Ruggeri and Ruggieri – position as one of the preeminent figures in violin making history, details about his life and work remain shrouded in mystery. Historical documents about him are in fact relatively rare – which is not that surprising considering he lived in the 17th century. Only a few official documents relating to him are available today, including his marriage contract, dated 1652, with Ippolita Ravasi (Cremona, parish of San Bernardo) and his death certificate, dated 28 October 1698 (parish of San Trinita). This would date his birth to around 1620-1630.

Various documents also indicate that Francesco Rugeri was nicknamed “Il Per”, in particular the labels in some of his instruments, inscribed “Rugeri detto il Per”, as well as several family documents from around 1660. It is possible that this nickname was added in order to distinguish him from other violin makers, in particular the Rogeri family of Brescia, active at the same time and whose instruments were sometimes mistaken for those of Francesco Rugeri.

Regarding his activity, we know that Francesco Rugeri worked at number 7 Contrada Coltellai, outside the walls of Cremona, in the parish of San Bernardo. From 1687, he was registered in the parish of San Sebastiano, next to the convent of San Sigismondo (Cremona). From around 1670, he was assisted by his three sons, Giovanni Battista, Giacinto and Vincenzo.

His instruments were renowned for their superior craftsmanship and tone, as well as for their refinement. They were sometimes passed off as works by Niccolò Amati. In 1685, violinist Tomaso Antonio Vitali brought a legal case to the Duke of Modena, following his purchase of a violin supposedly by Amati, which turned out to be by Rugeri. This illustrates the great similarity of making styles between these two legendary violin makers.

Francesco Rugeri is generally considered to be the first pupil of Niccolò Amati, although this is debatable, given the absence of any evidence of his apprenticeship in the Amati workshop census documents. However, it is possible that the absence of such document mentioning the name “Rugeri” can be explained by the fact that Francesco Rugeri did not reside with Amati during his apprenticeship, but in his own home instead, on the outskirts of Cremona. This is also consistent with the fact that the name of Antonio Stradivari, also considered a pupil of Amati, does not appear in the workshop documents either. There are several clues that point to Francesco Rugeri having been a pupil of Amati. As mentioned above, there are a great stylistic similarities between some of Rugeri’s instruments and those of Amati, suggesting he was trained by him [1]. Also, the Rugeri family lived just outside the city of Cremona, in the parishes of San Bernardo and San Sebastiano, and their proximity to the Amati workshop would make it entirely possible Rugeri could have apprenticed with Amati. A small violin by Niccolò and Girolamo Amati, sold at Vichy Enchères in 2021, supports this theory, as it has a head that betrays the hand of Francesco Rugeri.

[1] Wurlitzer, W. Henry Hill, Arthur F. Hill and Alfred E. Hill ; with a new introduction by Sydney Beck and new supplementary indexes by Rembert (1963). Antonio Stradivari : his life and work, 1664–1737 (New Dover ed.). New York: Dover. pp. 27 and 31.

The cello in the sale of 6 June 2024, which was made around 1680, also points to the influence of Amati.

“Rugeri was probably a pupil of Amati, and certain details of this cello are indeed reminiscent of Amati’s work, particularly the treatment of the f-holes and the head.”

Interview with Jonathan Marolle, Vatelot-Rampal, Paris, violin maker, specialist in string instruments, expert at the Paris Court of Appeal.

In addition, there are Rugeri instruments labelled with the mention “Alumnus Nicolai Amati”, such as a 1663 violin labelled “Francescus Rugerius Alumnus Nicolai Amati fecit Cremonæ 1663”. Therefore, Rugeri claimed to be a student of Amati. Was this a way of claiming to be part of the Amati school (which would have been commercially beneficial for him), or a statement of fact? The question remains.

However, one thing is certain: the Rugeri and Amati families were very close. For instance, Niccolò Amati was the godfather of Giacinto Rugeri, one of Francesco’s sons, baptized in 1658. Three decades later, in 1689, a grandson of Francesco Rugeri, in turn, had as godfather Girolamo Amati II – the then head of the family workshop after the death of his father in 1684.

Amongst the great mysteries surrounding the life of Francesco Rugeri, one of the most intriguing is undoubtedly that of his links with Antonio Stradivari. Recent research revealed that Antonio Stradivari might have been trained by Francesco Rugeri, not Niccolò Amati, as previously believed.

As mentioned above, the name of Stradivari does not appear anywhere in the historical documents regarding the Amati workshop – as is the case with Rugeri. Furthermore, Antonio Stradivari’s instruments diverge in many respects from those of Amati, whilst his early examples share many similarities with those of Francesco Rugeri.

The main difference between the work of Amati and Stradivari that has been put forward as evidence that Stradivari was apprenticed to Rugeri relates to the backs of Amati’s instruments, which have a small hole in their centre (used to graduate the thickness of the back). This technique, typical of Amati’s work, was used by all of his known pupils, with the exception of Antonio Stradivari or Francesco Rugeri. Since this process was not used in Francesco Rugeri’s production, and in light of the stylistic similarities between his instruments and those of Stradivari’s early period, it is entirely possible that Stradivari trained with Rugeri. (The age difference between Rugeri and Stradivari is consistent with this theory as well.)

Although belonging to the Amati school, Francesco Rugeri’s work is not a copy, but rather demonstrates his free and innovative spirit. The maker was particularly known for producing slightly larger and curvier models. Therefore, although Rugeri sometimes borrowed elements specific to Amati’s work, he also developed unique construction methods and distinctive details that rivalled the quality of Amati’s craftsmanship. His work is particularly distinctive by its careful execution, particularly in evidence in the skilful and uniform application of his bright varnishes, in shades typical of Cremona, ranging from dark orange to brilliant yellow-orange – as with the cello in the Vichy Enchères sale of 6 June 2024.

His most productive period was in the 1670s and 1680s, when he was assisted by his three sons. His success reached its peak after the decline of Nicolò Amati’s workshop and before the rise of that of Antonio Stradivari. Francesco Rugeri’s instruments quickly found success and were sought after for their superior craftsmanship and tone. The great names who owned instruments by Francesco Rugeri include Count Cozio di Salabue and the Marquis Castiglioni. However, few public collections hold instruments made by him. There is only one violin and one bass viol in the Musée de la Musique in Paris (late 17th century and 1699), two cellos in the Royal Academy of Music Museum (c.1689 and 1695, London), one violin in the Muziekinstrumentenmuseum (1690, Brussels), and a viola d’amore in the Scenkonstmuseet (1697, Stockholm).

Francesco Rugeri was true innovator, as demonstrated by the longevity of some of his designs. He left a lasting mark on the history of violin making mainly thanks to his magnificent cellos. He produced two types of different size, in order to adapt to the musical repertoire. The large one was more popular for the sacred repertoire, while the smaller one was mainly used for secular music. The cello in the Vichy Enchères sale on 6 June 2024 is a fine example of the so-called large type. Its full and elegant curves are typical of Rugeri’s work, and are enhanced by a delicate varnish.

This cello was made around 1680 and is one of the rare examples of this type to have survived. Indeed, only a third of the 30 or so instruments by the master auctioned in the 21st century were cellos.

Francesco Rugeri is also known for setting the standard size and proportions of the cello with his smaller model, which remains the standard size for cellos in use today. At the time, this was revolutionary, as this smaller model was 10 centimetres shorter than those of other Cremonese violin makers. This reduced size was immediately popular with musicians, as it made the instrument easier to carry and play.

In addition to their distinctive appearance, Francesco Rugeri’s cellos were renowned for their deep and rounded tone.

Francesco Rugeri marked the history of violin making thanks to the quality of his work and his innovative spirit. The craftsmanship and techniques he developed were subsequently used and passed on by his three violin-making sons and by his apprentices – including perhaps Stradivari (see above).

Amongst the sons of Francesco Rugeri who became violin makers, the eldest, Giovanni Battista Rugeri (1653 – 1711), was the first, and he worked in his father’s workshop. His production was limited and remains little known. One of his sons was the nephew of Hieronymus Amati II – another evidence of the close relationship between the two families.

Francesco Rugeri’s second son, Giacinto (1661 – 1697, not to be confused with Niccolò Amati’s nephew who died in infancy), also worked in the family workshop. His instruments are, like those of his brother, very rare. He had a son who was a violin maker, but no information exists about his work.

Finally, Vincenzo Rugeri (1663 – 1719), Francesco’s third son, was also active in the family workshop. He is the best known of the three sons, and was as renowned as his father. He is sometimes considered to be the best violin maker in the family, although his instruments are often comparable in quality to those of Francesco Rugeri. Vincenzo Rugeri also left his mark on the history of violin making, and he is thought to have been Carlo Bergonzi’s first tutor.

All were trained by Francesco Rugeri, in the family workshop, where they made instruments for him or with him. After their training, around the 1690s, the three sons settled in Cremona, in the vicinity of the Amati, Guarneri and Stradivari workshops, thus perpetuating the family tradition.

We hope to see you at Vichy Enchères on 6 June 2024 for the sale of this rare cello by Francesco Rugeri.