Lors de notre dernière vente de vents et d’instruments à cordes pincées, le 1er mai 2021, une très rare flûte à bec des années 1730, réalisée par Johann Heinrich Eichentopf, était présentée aux enchères et vendue 27.280€ (avec frais). Le 6 novembre 2021, à l’occasion de notre nouvelle vente de vents et d’instruments à cordes pincées, vous aurez l’opportunité de découvrir une flûte à bec alto en fa de la même époque, d’un facteur également très rare sur le marché : William Cotton (circa 1708 – 1775). Celle-ci nous livre un témoignage de la facture londonienne durant le XVIIIème siècle, des relations entre les facteurs et du goût européen pour l’instrument – encore apprécié dans les cours royales à en juger par sa prestigieuse provenance…

La flûte est estampillée “COTTON” sur la patte et la tête. Ce nom renvoie à une famille de facteurs anglais résidant à Londres, dont trois membres sont connus : William Cotton (c.1708 – 1775), son fils Robert Cotton (c.1735 – 1806) et John Cotton, probablement le neveu de Robert auprès de qui il rentre en apprentissage en 1784[1], également renommé en tant que violoniste.

[1] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill Index, 1993, Tony Bingham, p.72.

Les instruments de ces facteurs sont extrêmement rares sur le marché et dans les collections publiques. Nous connaissons uniquement un flageolet par Robert Cotton conservé au Royal College of Music de Londres (1770-94).

Les Cotton étaient installés à Bride Court, Bride Lane, Fleet Street, puis au 8 Parsons Court, Bride Lane, Fleet Street à partir de juin 1776[1]. William Cotton est le facteur le plus important de la famille, actif pendant plus de 45 ans. Sur sa carte de marchand – par chance conservée au British Museum – il se présente comme un facteur de toutes sortes d’instruments à vent :

“Wind instrument maker, at the Hautboy and two Flutes in Bride Lane Court near Fleet Street, London. Makes and sells all sorts of Wind Instruments, viz. Bassoons, Hautboys, German and Common Flutes in ye neatest Manner. N.B. All Sorts of Instruments mended.”

Stylistiquement, cette carte est proche de celles d’autres facteurs anglais actifs dans les années 1730-1740[1]. En outre, le nom de l’atelier The Hautboy and two Flutes ainsi que l’illustration confirment l’importance de la flûte à bec dans sa production. En effet, parmi les trois instruments figurés sur la carte, se trouve une flûte à bec.

[1] Simon Waters, A French Connection: Further light on Urquhart and Cotton, online

À la différence de son fils Robert, également connu en tant que “Flute-Maker”[1], William estampille ses instruments par son simple nom, comme c’est le cas de la flûte de la vente Vichy Enchères. On l’a dit, les instruments qu’il a réalisés et que l’on connaît sont rares. On compte un hautbois estampillé « Cotton/ Bride Lane/ Fleet St./[London] », probablement modifié par Robert ou John ; une flûte en buis conservée dans une collection suisse et estampillée “Cotton/[fleur de lys]” et une flûte d’amour appartenant à la collection de Guy Oldham[2].

[1] Joseph Doane, A Musical Directory for the Year 1794, Londres, 1794, p.15.

[2] Cet inventaire a été réalisé par Simon Waters dans “An Indigenous London Flute-Making Practice in the Early Eighteenth Century: The Case of Patrick Urquhart”, 2021.

En 1759, il assure ses biens et son activité de fabricant de flûtes auprès du Sun Fire Office et en décembre 1774 – alors atteint de la jaunisse, la maladie qui va l’emporter – il rédige son testament. Ce document nous apprend qu’il était “Merchant Taylor”, tout comme son maître : Patrick Urquhart (c.1668 – 1728)[1].

[1] Simon Waters, op.cit. 2021.

Ce lien entre William Cotton et Patrick Urquhart est essentiel pour comprendre la production du premier. Leur contrat stipule que Cotton entre en apprentissage auprès d’Urquhart en novembre 1722, à l’âge de 18 ans, pour une durée de sept ans. Cependant, la formation est écourtée par la mort du maître un an avant la fin fixée à 1729[1]. Néanmoins, Cotton reste marqué par le style de son maître, comme en témoigne une flûte d’Urquhart réalisée vers 1700 et vendue à Vichy Enchères en 2014, dont la composition est proche de celle de la flûte de Cotton de la prochaine vente.

[1] London Metropolitan Archives : Reference Number: COL/CHD/FR/02/0568-0573, citée dans Simon Waters, op. cit. 2021.

L’engagement d’Urquhart et de Cotton auprès de la Merchant Taylor’s Company est importante puisqu’il est peu probable que la société, qui supervisait alors l’apprentissage de Cotton auprès d’Urquhart, l’ait laissé apposer son nom sur des instruments avant la fin du contrat en 1729[1]. En outre, Cotton a certainement dû terminer les instruments inachevés d’Urquhart à sa mort en 1728.

[1] Simon Waters, A French Connection: Further light on Urquhart and Cotton, online

Ces considérations étant faites, il est tentant de penser que la flûte à bec de la prochaine vente estampillée “COTTON” fut réalisée au début de sa carrière, vers 1730, alors qu’il était encore imprégné du style de Patrick Urquhart. Il pourrait même s’agir d’un instrument débuté par Urquhart et achevé par Cotton. En effet, la ressemblance de cette flûte avec les modèles connus du maître est saisissante.

“What is clear, given its close similarity to Urquhart’s own instruments, is that this particular instrument dates from relatively early in Cotton’s output, and a date of 1729-40 therefore seems plausible.”

Simon Waters, A French Connection: Further light on Urquhart and Cotton, online

On pense notamment à l’instrument du Colonial Williamsburg (Virginie), daté vers 1710, et à la flûte de la Bate Collection of Musical Instruments de l’Université d’Oxford réalisée vers 1720. Ces deux modèles sont quasiment identiques à la flûte à bec alto en buis et montures en ivoire de Cotton de la vente Vichy Enchères du 6 novembre 2021. Tous témoignent d’une qualité d’exécution et d’un savoir-faire exceptionnels.

Cette grande ressemblance permet également de renforcer l’idée selon laquelle il existait dans les années 1700-1740 plusieurs réseaux de facteurs londoniens travaillant conjointement, sans attacher d’importance à estampiller leurs productions de leur nom. Il n’y avait aucun conflit entre les facteurs produisant des instruments portant leur propre marque et ceux qui produisaient des instruments similaires destinés à être vendus sous un autre nom. On retrouve ainsi peu d’instruments estampillés Urquhart et Cotton, ce qui ne signifie pas qu’ils aient peu produit. L’inventaire après décès d’Urquhart est d’ailleurs stupéfiant, puisqu’il comptabilise 686 flûtes à bec[1]! Urquhart, aidé d’apprentis comme Cotton, fabriquait très certainement des instruments pour d’autres facteurs.

[1] Simon Waters, op. cit., 2021, p. 110.

C’est Jeremy Montagu, conservateur à la Bate Collection of Musical Instruments et maître de conférences à l’Université d’Oxford, qui a le premier découvert ce mode de fonctionnement en s’intéressant au lien entre Urquhart et Pierre Jaillard – dit Bressan (1663-1731)[1]. Il a suggéré qu’Urquhart était le véritable fabricant de la plupart des instruments connus portant l’estampille Bressan et que ce dernier – évoluant dans les hautes sphères de la société – était responsable de la clientèle. C’est la similitude des instruments estampillés Bressan avec ceux d’Urquhart qui a conduit Jeremy Montagu à mettre en évidence cette organisation caractéristique des facteurs londoniens de l’époque. Cette hypothèse a été reprise et développée par Simon Waters[2].

[1] Jeremy Montagu, “As Like as Two Peas”, FoMRHIQ 92, Comm.1588, 1988, pp.1–2.

[2] Simon Waters, op. cit., 2021.

Suivant la même logique, il a été montré que William Cotton aurait travaillé, à la mort de son maître Urquhart, pour Stanesby Junior. En effet, certaines flûtes estampillées Stanesby ou Cotton sont stylistiquement très proches. Simon Waters nous donne deux exemples : une flûte en buis conservée dans une collection suisse estampillée “Cotton/[fleur de lys]” présentant un modèle similaire à ceux de Thomas Stanesby Junior ; et une flûte d’amour de Cotton appartenant à la collection de Guy Oldham, également similaire en termes de proportions et de style à celles de Stanesby[1]. Comme Bressan, il est possible que Stanesby ait pris en charge la gestion des clients et ait délégué la fabrication à un facteur talentueux et de confiance – en l’occurrence Cotton[2].

[1] Simon Waters, op. cit., 2021, p. 107.

[2] Voir l’article de Simon Waters dans le Galpin Society Journal LXXIV, pour plus d’informations.

Ainsi, Urquhart et Cotton ont certainement fourni d’autres facteurs, ce qui expliquerait pourquoi les flûtes estampillées Bressan, Urquhart, Cotton ou encore Stanesby sont parfois très semblables. En témoigne cet instrument de Bressan (c. 1720, voir ci-dessous) conservé à la Bate Collection of Musical Instruments de l’Université d’Oxford, réellement proche de notre flûte Cotton de la vente du 6 novembre 2021 ou ce modèle de Stanesby Senior de l’Horniman Museum and Gardens (voir ci-dessous).

Nous intégrons Stanesby Senior dans cette école stylistique londonienne puisqu’il œuvrait au sein du même réseau avec Thomas Garrett et Stanesby Junior, pour la Turner’s Company. Cette organisation était similaire à celle des Merchant Taylors qui, nous l’avons vu, réunissait Cotton, Urquhart, mais aussi son maître : Mary Woolstonecraft[1]. Ce mode d’organisation commerciale typiquement londonien assurait ainsi une transmission des modèles entre plusieurs générations.

[1] Voir l’article de Simon Waters dans le Galpin Society Journal LXXIV, pour plus d’informations.

Quand on se penche sur la circulation du modèle, on se rend compte que la France semble avoir beaucoup participé à la diffusion de ce style de flûtes à bec. D’abord parce que Bressan, d’origine française, a certainement contribué à l’émergence du modèle en s’installant en Angleterre en 1683 avant de le transmettre à Urquhart. Bressan est d’ailleurs considéré par certains comme le chef de file de l’école anglaise d’instruments à vent. En outre, on retrouve quelques flûtes de ce style dans la production d’un autre français : Jean-Jacques Rippert (avant 1696 – 1716). Cette proximité stylistique des instruments de Bressan et Rippert conduit à penser qu’ils auraient eu le même maître. Selon certaines hypothèses, il s’agirait d’un membre de la famille Hotteterre.

Quoi qu’il en soit, il reste évident que des instruments comme la flûte à bec de Bressan du Horniman Museum and Gardens et celle de Rippert du musée de la Musique de Paris, ont beaucoup en commun (voir ci-dessous). À noter également – puisque les modèles sont assez rares pour se le permettre – que l’on retrouve quelques flûtes à bec de ce style en Allemagne. Il se pourrait, là encore, que le modèle provienne de France, via Rippert, qui fabriqua des flûtes à destination de l’Allemagne dès 1716 (“whose flutes he reported to be in demand as far away as Frankfurt”)[1]. Nous avons notamment connaissance d’un modèle similaire, réalisé par un membre de la famille Denner, conservé au Palais Lascaris à Nice.

[1] William Waterhouse, op. cit, p.329.

Enfin, la flûte de William Cotton de la vente du 6 novembre 2021 nous renseigne également sur la circulation du modèle, puisqu’elle offre un exemple d’instrument réalisé à Londres à destination de la France, alors qu’il est couramment admis que le commerce des instruments se faisait dans la direction inverse[1].

[1] Voir l’article de Simon Water « A French Connection: Further light on Urquhart and Cotton. »

En effet, outre les deux estampilles “COTTON”, la flûte est marquée “M.LE.D.DELUYNES/ N°1”, certainement en référence au propriétaire d’origine : le français Charles Philippe d’Albert, 4ème duc de Luynes. Une inscription qui entre en résonance avec la fleur de lys estampillée sur la flûte en buis de Cotton conservée dans une collection suisse (cf : 1er paragraphe). Celle-ci témoigne certainement d’une provenance française et d’un commanditaire issu d’une haute position sociale, à l’image du duc de Luynes.

Les ducs de Luynes ont reçu leur titre sous Louis XIII, grâce à Charles d’Albert (1578 – 1621), favori du roi avec qui il entretint, selon plusieurs historiens, des relations intimes. Les intérêts musicaux des ducs de Luynes sont bien connus depuis Charles d’Albert. On peut notamment lire dans le Journal de Jean Héroard Sur l’Enfance Et La Jeunesse de Louis XIII (1601-1628) que :

“le Sieur de Luynes, un gentilhomme qu’il [Louis XIII] aimoit, étoit habillé à la suisse, avoit des chausses jaunes découpées, une grosse brayette verte et une grande fraise pareil à celle des femmes, et qu’il jouoit du fifre”

Par ailleurs, la bibliothèque des ducs de Luynes, autrefois conservée au château de Dampierre et dispersée depuis 2013 par Sotheby’s, comprenait un grand nombre de partitions, parmi lesquelles des œuvres de Bach (1685-1750 ; ex: Six sonates pour Clavecin ou Piano forte avec accompagnement de violon ou flûte) et de Lully[1] (1632-1687 ; ex : Proserpine qui intègre des flûtes à bec). Ces compositeurs sont particulièrement intéressants puisqu’ils ont inclus la flûte à bec dans leur œuvres[2].

[1] Voir Laurence Pottier, La flûte à bec dans les Tragédies en musique de Lully, thèse, Sorbonne Paris-IV, 1987.

[2] Voir Laurence Pottier, Le répertoire de la flûte à bec en France à l’époque baroque, thèse, Sorbonne Paris-IV, 1992.

Concernant l’identité précise du duc de Luynes, la datation de la flûte vers 1729-1740 nous amène à Charles Philippe d’Albert de Luynes, duc de 1712 à 1758, représenté par Carmontelle l’année de sa mort (dessin conservé au musée Condé de Chantilly)

Ce dernier est le plus célèbre de la lignée grâce aux Mémoires sur la Cour de Louis XV (1735-1758) qu’il publia en 17 volumes. En effet, sa femme Marie Brûlart de La Borde était la première dame d’honneur de la reine Marie Leszczynska et le couple faisait partie des intimes de la famille royale. Dans ses Mémoires, le duc rapporte que la reine soupa plus de 200 fois dans l’appartement de Marie Brûlart situé au château de Versailles et qu’elle vint également plusieurs fois au château de Dampierre – leur résidence principale. Ce monumental ouvrage est un précieux document pour l’étude de la société aristocratique et bien qu’il ne soit pas une biographie et ne renseigne pas sur la pratique instrumentale du duc, on trouve plusieurs commentaires pointus sur l’exécution de pièces musicales qui laissent entendre qu’il maîtrisait le sujet. En 1747, il commente notamment la performance de Louis-Gabriel Guillemain qui joue en soliste “plusieurs petits airs doublés, triplés et brodés avec tout l’art possible […] ces duos […] sont d’une exécution très difficile”[1]. Enfin, à la Cour, le duc était en contact avec les plus grands musiciens de l’époque – tels que Blavet, “célèbre joueur de flûtes” – comme nous le confirment ses chroniques[2].

Outre le fait que la flûte ait appartenu à cette éminente figure de la cour de Louis XV, elle est d’autant plus exceptionnelle que sa marque “N°1” indique certainement que l’instrument fut le préféré, ou le meilleur, du duc de Luynes[3].

[1] Louis Dussieux et Eudoxe Soulié, Mémoires du duc de Luynes sur la Cour de Louis XV (1735-1758), 17 volumes in-8o, Paris, Firmin-Didot frères, 1860-1865.

[2] Cité par Simon Waters dans son article en ligne : « “Blavet, célèbre joueur de flûtes” » fait une apparition aux pp.292-3 du tome 2, le lundi 22 décembre 1738, ayant apparemment terminé son rendez-vous de 1500 livres pour avoir visité la cour seulement six fois en un an.»

[3] Nous remercions Simon Waters pour cette information.

Bien que la flûte à bec soit délaissée à partir de la fin du XVIIIème siècle, il n’est pas étonnant d’en trouver de beaux modèles dans les plus grandes collections d’Europe de la première moitié du siècle. À cette époque, plusieurs facteurs et compositeurs travaillaient à la renommée de l’instrument. Stanesby prétendait ainsi faire de la flûte à bec ténor la véritable flûte de concert et Jacques Hotteterre écrivait les Principes de la flûte à bec en 1707 en soulignant que la flûte à bec alto en fa – à l’instar de celle du duc de Luynes – était la flûte du soliste par excellence.

Plusieurs compositeurs réalisaient des œuvres importantes pour elle – on a déjà cité Bach (ex : Concerto pour clavecin, deux flûtes à bec et cordes, en fa majeur, BWV 1057, vers 1738) – mais on pense aussi à Georg Friedrich Haendel (1685-1759) et à ses Six sonates pour flûte à bec et continuo composées vers 1725-1726 pour l’usage privé de la famille royale britannique.

Une intéressante huile sur toile réalisée vers 1715 par le peintre de cours royales Ján Kupecký – notamment à l’origine d’un portrait du roi d’Angleterre – dépeint probablement Haendel jouant de la flûte à bec. Le tableau est d’ailleurs conservé dans la maison natale de Haendel, transformée en musée (Händel-Haus, Saale, Allemagne). Témoignant de l’importance de cette peinture, une copie a été réalisée et est visible au musée des Beaux-Arts de Budapest (Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, Hongrie). Cette œuvre a le double intérêt de confirmer le goût de Haendel pour la flûte à bec (même si le portrait n’est que présumé, le tableau se situe dans sa maison), et de figurer une flûte à bec de même modèle que celle de Cotton ayant appartenu au duc de Luynes.

La peinture est encore plus intéressante lorsque l’on considère que Haendel s’installe en Angleterre en 1712 (il se fera naturaliser anglais), et que ce type de flûte est typique de la facture londonienne de l’époque. Que Haendel compose des sonates pour flûtes à bec pour la famille royale d’Angleterre et qu’il se fasse portraiturer jouant de l’instrument vers 1715, démontrent que ce dernier était encore en vogue au début du siècle. Ajoutons que l’on connaît un autre tableau de Ján Kupecký représentant un homme de qualité tenant une flûte à bec de style londonien, conservé au Kunsthall de Hambourg, qui pourrait aussi être un portrait de Haendel.

Un autre exemple fameux atteste de la vogue pour la flûte à bec durant la première moitié du XVIIIème siècle : celui du musicien et compositeur anglais William Babell (1690-1723). Celui-ci composa diverses œuvres pour elle, telles que ce Concerto pour flûte à bec en ré majeur op. 3 n° 2 . Il se fit également portraiturer, vers 1705, avec une flûte présentant des similitudes à celle de Cotton de la vente du 6 novembre 2021 (auteur et localisation inconnus). L’instrument jouissait donc encore d’un certain succès dans la première moitié du XVIIIème et les meilleurs facteurs étaient sollicités par les cours royales (au moins celles d’Angleterre et de France).

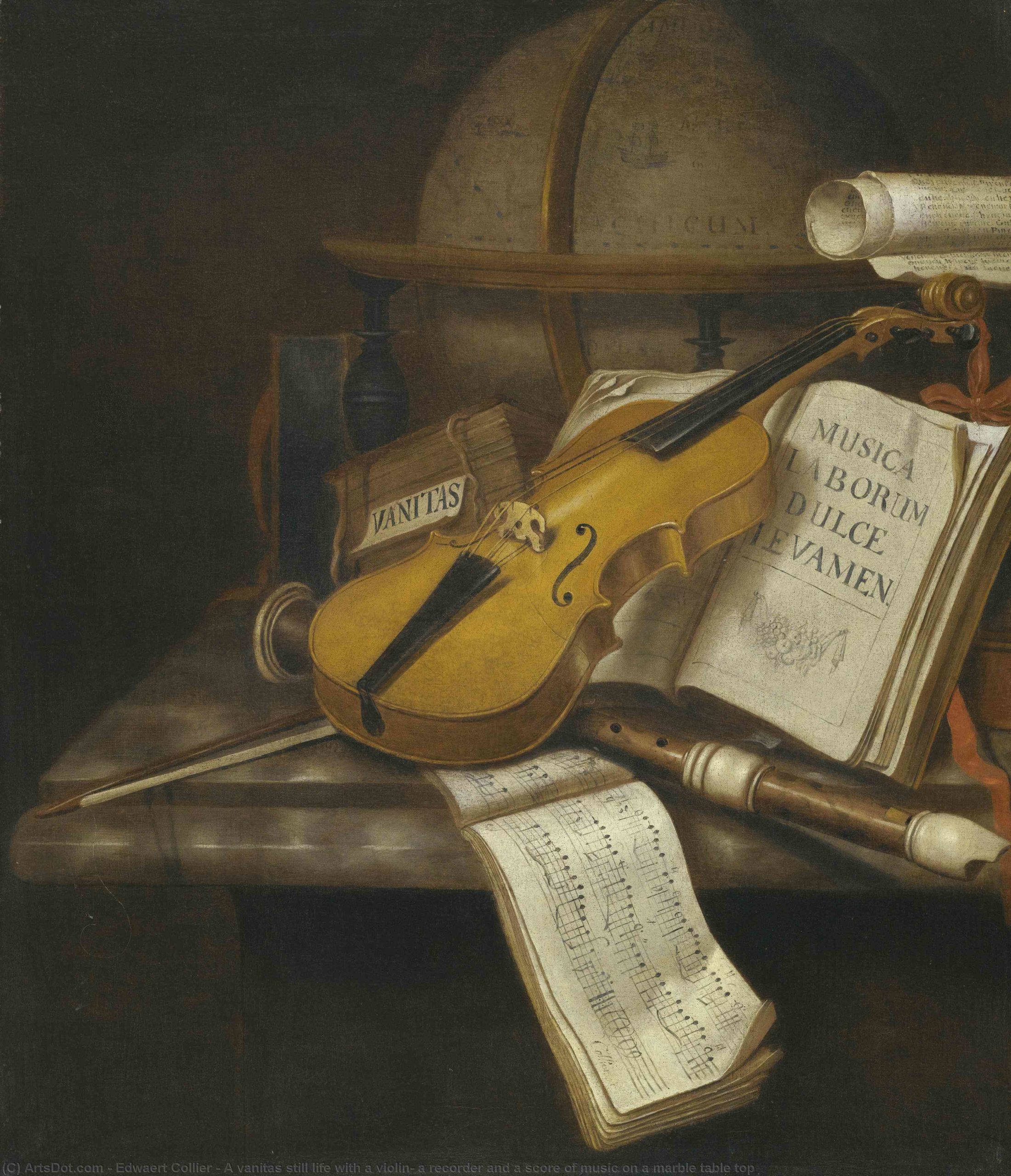

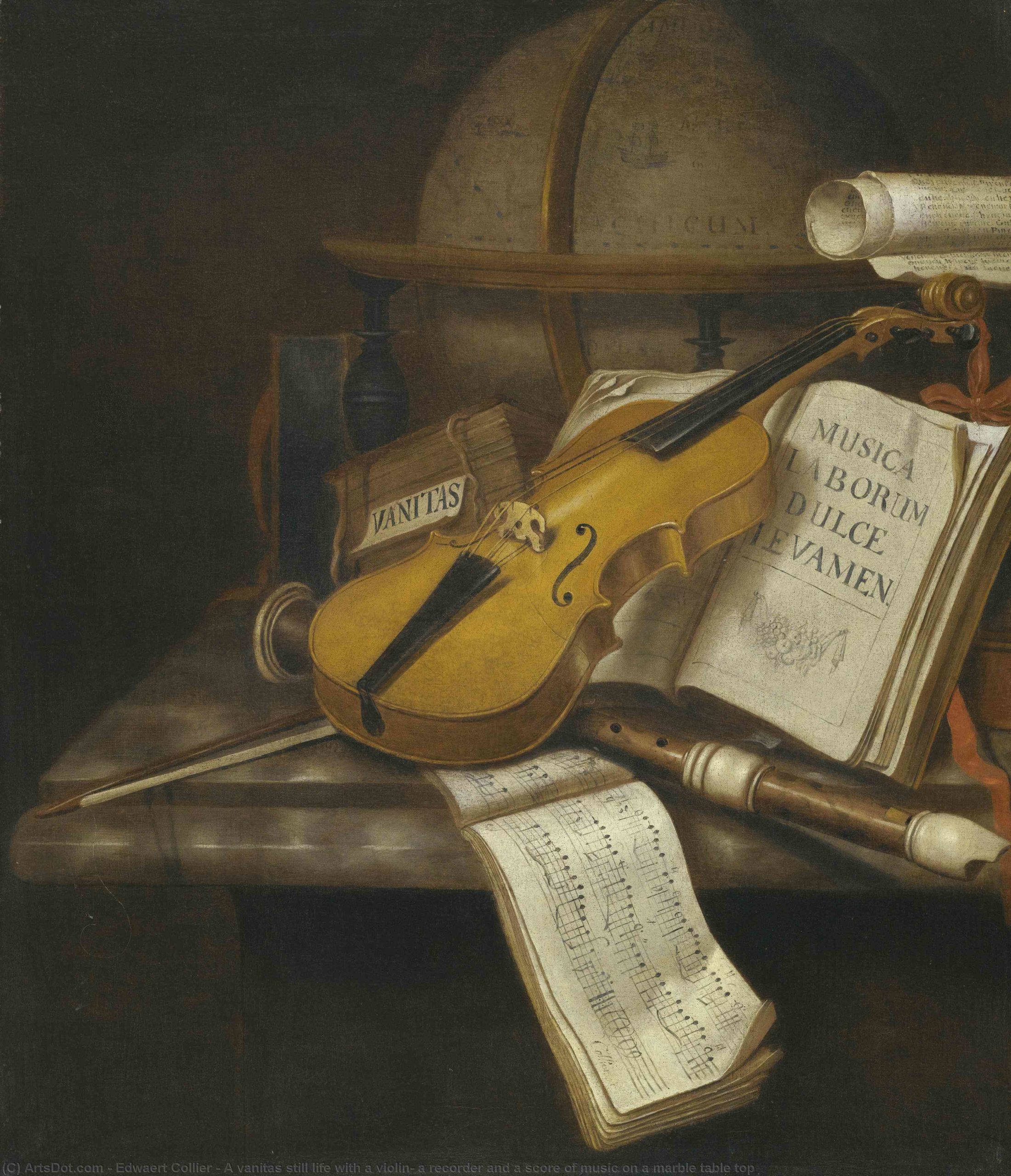

Il n’est pas étonnant que Cotton ait fait partie de ces prestigieux facteurs lorsque l’on considère son savoir-faire et ses relations. Son lien avec Urquhart l’a peut-être rapproché des familles royales, puisque le père de celui-ci, le luthier Thomas Urquhart, avait établi des relations étroites avec les musiciens royaux en travaillant pour la Chapelle royale[1]. Enfin, pour le plaisir mais aussi parce que l’exemple est significatif, le peintre Edwaert Collier – installé définitivement en Angleterre à partir de 1706 – choisit d’intégrer dans ses natures mortes plusieurs flûtes à bec semblables à celle du duc de Luynes réalisée par Cotton.

[1] Simon Waters, op.cit. 2021, p.108.

Nous remercions chaleureusement Simon Waters pour son aimable concours.

Retrouvez son article en ligne sur son site www.simonwaters.net.

Our last sale of wind and plucked string instruments, on 1 May 2021, included a very rare recorder from the 1730s, made by Johann Heinrich Eichentopf, which sold for €27,280 (including fees). Our upcoming sale of wind and plucked string instruments on 6 November 2021 will provide the opportunity to discover an alto recorder in F from the same period, made by a maker rarely seen on the market: William Cotton (circa 1708 – 1775). This instrument attests to the London craftsmanship during the first half of the 18th century, the relationships between makers, and the European taste for the instrument – which was still appreciated in the royal courts, judging from its prestigious provenance.

The flute is stamped “COTTON” on the foot joint and the head. This name refers to a family of English makers established in London, of which three members are known to us: William Cotton (c.1708 – 1775), his son Robert Cotton (c.1735 – 1806), and John Cotton, who was probably Robert’s nephew from whom he apprenticed in 1784[1], and who was also renowned as a violinist.

[1] William Waterhouse, The New Langwill Index, 1993, Tony Bingham, p.72.

Instruments by these makers are extremely rare on the market and in public collections. We only know of a flageolet by Robert Cotton kept at the Royal College of Music in London (1770-94).

The Cottons were established at Bride Court, Bride Lane, Fleet Street, and then at 8 Parsons Court, Bride Lane, Fleet Street from June 1776[1]. William Cotton was the most important maker in the family, and was active for over 45 years. On his business card – which, by good fortune, is kept in the British Museum – he presented himself as a maker of all kinds of wind instruments:

“Wind instrument maker, at the Hautboy and two Flutes in Bride Lane Court near Fleet Street, London. Makes and sells all sorts of Wind Instruments, viz. Bassoons, Hautboys, German and Common Flutes in ye neatest Manner. N.B. All Sorts of Instruments mended.”

Stylistically, this business card is similar to those of other English makers active in the years 1730-1740[1]. Moreover, the name of the workshop, The Hautboy and two Flutes, as well as the illustration on the card, confirm the importance of the recorder in his production. Indeed, among the three instruments shown on the card, one is a recorder.

[1] Simon Waters, A French Connection: Further light on Urquhart and Cotton, online

Unlike his son Robert, who was also known as a “Flute-Maker”[1], William stamped his instruments with simply his name, as is the case with the flute in the Vichy Enchères sale. As previously discussed, known instruments by this maker are rare. We know of an oboe stamped « Cotton/Bride Lane/Fleet St./[London] », probably modified by Robert or John; a boxwood flute kept in a Swiss collection and stamped « Cotton/[fleur de lys] »; and a love flute in the collection of Guy Oldham[2].

[1] Joseph Doane, A Musical Directory for the Year 1794, London, 1794, p.15.

[2] This inventory was carried out by Simon Waters in “An Indigenous London Flute-Making Practice in the Early Eighteenth Century: The Case of Patrick Urquhart”, 2021.

In 1759, he insured his assets and his activity as a flute maker with the Sun Fire Office and in December 1774 – by then suffering from jaundice, the disease that was to kill him – he wrote his will. This document tells us that he was “Merchant Taylor”, just like his master Patrick Urquhart (c.1668 – 1728)[1].

[1] Simon Waters, op.cit. 2021.

The link between William Cotton and Patrick Urquhart is key to understanding the production of the former. Their contract stipulated that Cotton started his apprenticeship with Urquhart in November 1722, at the age of 18, for a period of seven years. However, the training was cut short by the death of the master a year before the contract’s end date of 1729[1]. Nevertheless, Cotton remained influenced by the style of his master, as evidenced by an Urquhart flute made around 1700 and sold at Vichy Enchères in 2014, whose making is similar to that of the Cotton flute in the upcoming auction.

[1] London Metropolitan Archives: Reference Number: COL / CHD / FR / 02 / 0568-0573, cited in Simon Waters, op. cit. 2021.

Urquhart and Cotton’s involvement with the Merchant Taylor’s Company is significant as it is unlikely that the company, which supervised Cotton’s apprenticeship with Urquhart at the time, would let him put his name on instruments before the end of the contract in 1729[1]. In addition, it is probable Cotton was tasked with completing the instruments of Urquhart unfinished upon his death in 1728.

[1] Simon Waters, A French Connection: Further light on Urquhart and Cotton, online

Considering the above, it is likely that the recorder stamped « COTTON » in the next sale was made at the beginning of his career, around 1730, while he was still influenced by the style of Patrick Urquhart. It could even be an instrument started by Urquhart and finished by Cotton. Indeed, the similarity of this flute with the known models by the master is striking.

“What is clear, given its close similarity to Urquhart’s own instruments, is that this particular instrument dates from relatively early in Cotton’s output, and a date of 1729-40 therefore seems plausible.”

Simon Waters, A French Connection: Further light on Urquhart and Cotton, online

In particular, the instrument of Colonial Williamsburg (Virginia), dated from around 1710, and the flute of the Bate Foundation in Oxford made around 1720 come to mind. These two models are almost identical to the ivory mounted boxwood alto recorder by Cotton in the Vichy Enchères sale of 6 November 2021. All of three of them bear witness to the exceptional quality of their making and craftsmanship.

This strong resemblance also reinforces the idea that in the 1700s and 1740s there were several networks of London makers working together, and that they were not concerned with stamping their names on their instruments. There was no conflict between the makers producing instruments bearing their own brand and those producing similar instruments intended to be sold under another name. As a result, there are few instruments stamped Urquhart and Cotton, which does not mean that their output was limited. Urquhart’s inventory after his death is staggering, and included 686 recorders[1] ! Urquhart, assisted by apprentices like Cotton, most likely made instruments for other makers.

[1] Simon Waters, op. cit., 2021, p. 110.

It was Jeremy Montagu, curator at the Bate Collection, who first discovered this modus operandi by examining the link between Urquhart and Pierre Jaillard – aka Bressan (1663-1731)[1]. He suggested that Urquhart was the maker behind most of the well-known Bressan-stamped instruments, and that Bressan – who was well connected among the upper classes – was in charge of dealing with customers. It is the similarity of the instruments stamped Bressan with those of Urquhart that led Jeremy Montagu to highlight this business organization, typical of the London makers of the time. This idea was revived and further developed by Simon Waters[2].

[1] Jeremy Montagu, “As Like as Two Peas”, FoMRHIQ 92, Comm.1588, 1988, pp.1–2.

[2] Simon Waters, op. cit., 2021.

Following the same logic, it was deduced that William Cotton would have worked, after the death of his master Urquhart, for Stanesby Junior. Indeed, some flutes stamped Stanesby or Cotton are stylistically very close. Simon Waters gives us two examples: a boxwood flute kept in a Swiss collection stamped “Cotton/[fleur-de-lis]” on a model similar to those of Thomas Stanesby Junior; and a Cotton love flute from the Guy Oldham collection, also similar in proportions and style to that of Stanesby[1]. Like Bressan, it is possible that Stanesby took over customer duties and delegated the manufacturing to a talented and trusted maker – namely Cotton[2].

[1] Simon Waters, op. cit., 2021, p. 107.

[2] See the article by Simon Waters in the Galpin Society Journal LXXIV for more information.

Therefore, Urquhart and Cotton supplied other makers, which would explain why the flutes stamped Bressan, Urquhart, Cotton or even Stanesby are sometimes very similar. This is evidenced by this instrument by Bressan (c. 1720, see below) kept in the Bate Collection, very closely related to our Cotton flute in the sale of 6 November 2021, or this model by Stanesby Senior from the Horniman Museum and Gardens (see below).

We include Stanesby Senior in this London School, as he worked in the same network as Thomas Garrett and Stanesby Junior, making instruments for the Turner’s Company. This company was similar to the Merchant Taylors’, which, as previously mentioned, brought together Cotton, Urquhart, but also his master: Mary Woolstonecraft[1]. This business model, typical of London, therefore ensured that models were passed on from generation to generation.

[1] See the article by Simon Waters in the Galpin Society Journal LXXIV for more information.

When we examine the spread of this style of recorders, it is clear that France seems to have had a lot to do with it. Firstly, through Bressan, who was originally from France, but settled in England in 1683 and most probably contributed to the rise of the model there, before passing it on to Urquhart. Bressan is considered by some as the leading figure of the English school of wind instrument making. In addition, we find some flutes of this style in the production of another Frenchman: Jean-Jacques Rippert (before 1696 – 1716). The stylistic similarity of the instruments by Bressan and Rippert suggests that they had the same tutor. Some believe he was a member of the Hotteterre family.

Either way, it remains clear that instruments like Bressan’s recorder from the Horniman Museum and Gardens and Rippert’s one from the Musée de la Musique in Paris have a lot in common (see below). It is also worth noting, since such examples are so rare, that a few recorders of this style exist in Germany. Once again, the model could have come from France, via Rippert, who made flutes for the German market as early as 1716 (“whose flutes he reported to be in demand as far away as Frankfurt”[1]. We are aware in particular of a similar example, made by a member of the Denner family, kept at the Palais Lascaris in Nice.

[1] William Waterhouse, op. cit, p.329.

Finally, William Cotton’s flute in the sale of 6 November 2021 also provides an interesting insight into the commercial flow of such models, since it is an example of an instrument made in London for France, while it is commonly accepted that the trading in such instruments was generally carried out in the opposite direction[1].

[1] See Simon Water’s article « A French Connection: Further light on Urquhart and Cotton. »

Indeed, in addition to the two stamps “COTTON”, the flute is stamped “M.LE.D.DELUYNES / N°1”, probably in reference to the original owner: the French Charles Philippe d’Albert, fourth Duke of Luynes. This inscription echoes the fleur-de-lis stamped on the Cotton boxwood flute kept in a Swiss collection (see first paragraph), which most likely attests to its French origin and a patron of high social status, such as the Duke of Luynes.

The Dukes of Luynes received their title under Louis XIII, thanks to Charles d´Albert (1578 – 1621), a favourite of the King with whom he maintained, according to several historians, intimate relations. The musical interests of the Dukes of Luynes have been well documented since Charles d’Albert. We can read in particular in the Journal de Jean Héroard Sur l’Enfance et La Jeunesse de Louis XIII (1601-1628) that:

“The Sieur de Luynes, a gentleman whom he [Louis XIII] loved, was dressed in Swiss style, had yellow shoes with cut-outs, a big green brayette and a large strawberry ruff like that of women, and that he played the fife.”

In addition, the library of the Dukes of Luynes, formerly kept at the castle of Dampierre and auctioned in 2013 by Sotheby’s, included a large number of scores, including works by Bach (1685-1750; e.g. Six sonatas for harpsichord or pianoforte with accompaniment of violin or flute) and of Lully[1] (1632-1687; e.g. Proserpine, which includes parts for the recorder). These composers are particularly interesting to us since they included recorder parts in their works[2].

[1] See Laurence Pottier, The recorder in Lully’s Tragedies in music, thesis, Sorbonne Paris-IV, 1987.

[2] See Laurence Pottier, The recorder repertoire in France in the baroque period, thesis, Sorbonne Paris-IV, 1992.

Concerning the precise identity of the Duke of Luynes, the dating of the flute of around 1729-1740 brings us to Charles Philippe d’Albert de Luynes, Duke from 1712 to 1758, represented by Carmontelle in the year of his death (drawing kept at the museum Condé in Chantilly).

He is the most famous of the line thanks to his Memoirs on the Court of Louis XV (1735-1758), which he published in 17 volumes. Indeed, his wife Marie Brûlart de La Borde was the first lady of honour to Queen Marie Leszczynska and the couple were close friends of the royal family. In his memoirs, the Duke reports that the Queen dined more than 200 times in Marie Burnart’s apartment in the Palace of Versailles and that she also visited the Château de Dampierre – their main residence – several times. This monumental work is a precious document for the study of aristocratic society, and although it is not a biography and does not provide information on the Duke’s instrumental practice, there are several pointed comments on the performance of musical pieces which suggest that he had mastered the subject. In 1747, he notably commented on the performance of Louis-Gabriel Guillemain, who played as a soloist « several short pieces doubled, tripled and ornamented in the most artistic manner […] these duets […] are very difficult to perform »[1]. Finally, at Court, the Duke was in contact with the greatest musicians of the time – such as Blavet, “famous flute player” – as his chronicles confirm to us[2].

Besides the fact that the flute belonged to this eminent figure of the Court of Louis XV, it is all the more exceptional as its stamp “N°1” probably indicates that the instrument was the favourite, or the best, of the Duke of Luynes[3].

[1] Louis Dussieux and Eudoxe Soulié, Memoirs of the Duke of Luynes on the Court of Louis XV (1735-1758), 17 volumes in-8o, Paris, Firmin-Didot frères, 1860-1865.

[2] Quoted by Simon Waters in his online article: “Blavet, famous flute player » appears on pp. 292-3 of volume 2, on Monday 22 December 1738, having apparently finished his meeting of 1,500 pounds for visiting the Court only six times in a year. ”

[3] We thank Simon Waters for this information.

Although the recorder was abandoned from the end of the 18th century, it is not surprising to find beautiful examples in the largest collections in Europe from the first half of the century. At that time, several makers and composers were working on making the instrument famous. For instance, Stanesby attempted to make the tenor recorder the true concert flute, and Jacques Hotteterre wrote the Principles of the recorder in 1707, in which he emphasized that the alto recorder in F – like the one owned by the Duke of Luynes – was the soloist’s flute par excellence.

Several composers produced important works for the instrument – we have already mentioned Bach (e.g. the Concerto for harpsichord, two recorders and strings, in F major, BWV 1057, circa 1738) – but we also think of Georg Friedrich Handel (1685- 1759) and his Six sonatas for recorder and continuo composed around 1725-1726 for the British royal family and intended for their private use.

An interesting oil on canvas – made around 1715 by Ján Kupecký, a royal court painter, very famous during his lifetime, who notably painted a portrait of the King of England – probably depicts Handel playing the recorder. The painting is also kept in Handel’s birthplace, which has been turned into a museum (Handel-Haus, Saale, Germany). Denoting the importance of this painting, a copy was made and can be seen at the Budapest Fine Arts Museum (Szépművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, Hungary). This work is interesting in both confirming Handel’s taste for the recorder (while the actual sitting of the portrait is only presumed, the painting is definitely set in his house), and for featuring a recorder of the same model as the one made by Cotton and owned by to the Duke of Luynes.

The painting is even more interesting when one considers that Handel settled in England in 1712 (he gained British citizenship), and that this type of flute is typical of the making in London at the time. The fact that Handel composed sonatas for recorders for the English Royal Family and that he was himself portrayed playing the instrument around 1715, shows that the instrument was still in vogue at the turn of the century. We should add that we know of another painting by Ján Kupecký of a man of standing holding a London-style recorder, kept at the Kunsthall museum in Hamburg, which could also be a portrait of Handel.

Another famous figure attests to the popularity of the recorder during the first half of the 18th century: the English musician and composer William Babell (1690-1723). He composed various works for it, such as his Concerto for Recorder in D major, Op. 3 n ° 2. He also had himself portrayed, around 1705, with a flute showing similarities to the one by Cotton in the sale of 6 November 2021 (artist and location unknown). The instrument therefore still enjoyed some success in the first half of the 18th century and the best makers were sought by the royal courts (at least those of England and France).

It’s not surprising that Cotton was among those prestigious sought-after makers when considering his craftsmanship and connections. His connection to Urquhart may have brought him closer to the royal families, as his father, luthier Thomas Urquhart, had established close relationships with royal musicians while working for the Royal Chapel[1]. Finally, for anecdotal value but also because the example is significant, the painter Edwaert Collier – who settled permanently in England from 1706 – chose to include in his still lives several recorders similar to the Cotton one belonging to the Duke of Luynes.

[1] Simon Waters, op.cit. 2021, p.108.

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to Simon Waters for his kind assistance in writing this article.

You can find his article online on his website: www.simonwaters.net.