La vente du 5 juin 2025 de Vichy Enchères comprend deux violons de Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume (1798–1875). L’un, daté de 1865, suivant un modèle Stradivarius ; l’autre, réalisé en 1871, offrant une interprétation du modèle Guarnerius. Ces deux instruments sont emblématiques de la dernière période de production du maître parisien – celle de la maturité artistique.

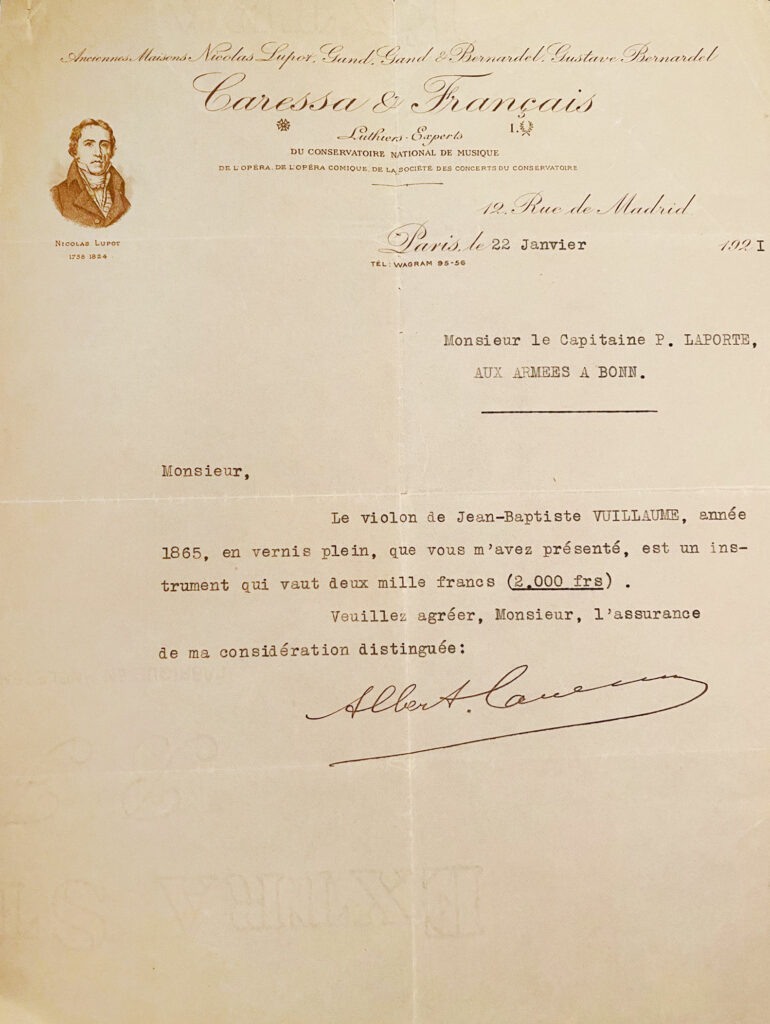

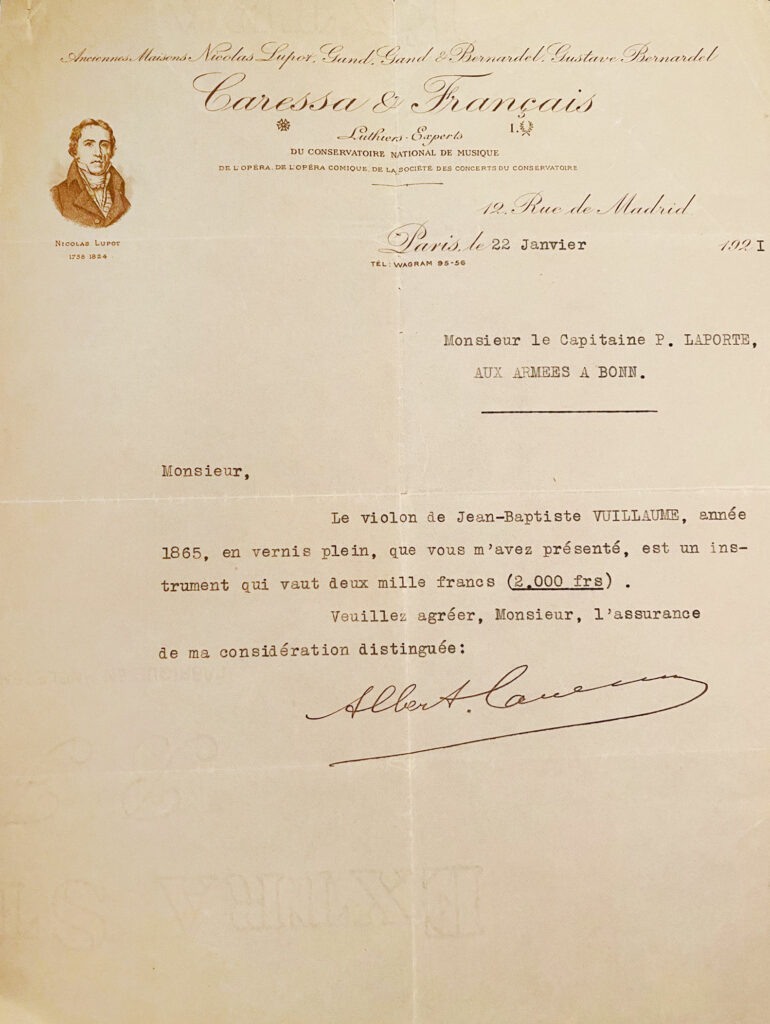

Le premier violon, fait en 1865, est en modèle Stradivarius et porte l’étiquette d’origine de la rue Demours avec paraphe manuscrit “65” et signature sur le fond. Il est dans un bon état de conservation et accompagné d’une copie d’un certificat Caressa & Français de 1921. Il convient de souligner l’importance de ce certificat sur le plan historique puisque la maison Caressa & Français, héritière de la prestigieuse lignée Gand & Bernardel, était au début du XXe siècle l’une des références mondiales en matière d’expertise et de commerce d’instruments à cordes.

Anciennement propriété du violoniste Paul Laporte dans les années 1920, l’instrument n’a jamais quitté sa famille.

Ce violon appartient à la phase tardive de Vuillaume, lorsque le luthier, ayant délégué la gestion commerciale de son atelier à ses associés – notamment à Georges Chanot – se consacre exclusivement à la fabrication.

Les modèles d’après Stradivarius constituent l’ossature de la production de Vuillaume. Le luthier étudia en profondeur le fameux “Messie” de 1716 – qu’il acquit et conserva – et multiplia les copies dans une optique expérimentale. Ses répliques, qui ne sont jamais des calques, trahissent un regard analytique et une volonté d’adaptation des modèles aux besoins des musiciens de son temps.

Le second violon, daté de 1871 et numéroté 2870, suit le modèle Guarnerius del Gesù. Il porte la même étiquette de la rue Demours, le paraphe manuscrit “71”, ainsi que la double marque au fer “Vuillaume” sur la table et le fond.

L’intérêt de Vuillaume pour Guarnerius apparaît dès les années 1835-1840, notamment après son étude approfondie du “Cannone” de Paganini.

L’instrument fait partie des derniers connus du luthier. Il porte le n°2870, sur une production de près de 3000 pièces référencées – un fait exceptionnel pour un luthier du XIXe siècle, qui résulte d’un atelier organisé comme une véritable manufacture, avec des maîtres d’œuvre tels que Derazey, Silvestre, Germain ou Maucotel.

Si Vuillaume s’est imposé comme le plus grand luthier français du XIXe siècle, c’est en raison de sa capacité à conjuguer une fascination érudite pour les maîtres italiens et une volonté constante d’expérimentation. Ses copies sont le produit d’une démarche presque scientifique, puisque Vuillaume prenait des empreintes, relevait les mensurations, étudiait le vernis, les bois, les voûtes et même la microstructure des instruments anciens – souvent grâce aux acquisitions du marchand Luigi Tarisio.

Comme en attestent ces nouveaux instruments, il ne se contenta jamais de reproduire et modifia les voûtes, ajusta les profils, allongea les touches, abaissa les hauteurs de table pour répondre aux attentes des musiciens et s’adapter au nouveau répertoire.

Ces deux instruments nous offrent un nouveau témoignage de la dualité de l’œuvre de Vuillaume – oscillant entre hommage aux modèles anciens et innovations – et nous proposent deux visions de perfection en matière de violons.

The Vichy Enchères sale on 5 June 2025 will include two violins by Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume (1798–1875). The first one is a Stradivarius model dating from 1865; the other, made in 1871, is an interpretation of the Guarnerius model. These two instruments are typical of the Parisian master’s final period of production, that of his artistic maturity.

The first violin, made in 1865, is a Stradivarius model and bears the original label of rue Demours with handwritten “65” for the last two digits of the year, and a signature on the back. It is in good condition and comes with a copy of a Caressa & Français certificate from 1921. The historical importance of this certificate is worth pointing out, as Caressa & Français, the heir to the prestigious Maison Gand & Bernardel, were world-renowned experts and dealers in stringed instruments in the early 20th century.

This instrument was formerly owned by violinist Paul Laporte in the 1920s, and it never left his family.

It belongs to Vuillaume’s late period, when the maker, having delegated the commercial management of his workshop to his partners – notably Georges Chanot, dedicated himself exclusively to making.

The Stradivarius models form the backbone of Vuillaume’s output. The violin maker studied extensively the famous « Messiah » of 1716 – which he acquired and kept – and made numerous copies of it as a form of experimentation. His interpretations, which are never exact replicas, attest to his analytical eye and a desire to create instruments that met the needs of the musicians of his time.

The second violin, dated 1871 and numbered 2870, follows the Guarnerius del Gesù model. It bears the same label of rue Demours, with handwritten “71” for the last two digits of the year, as well as the « Vuillaume » stamp on the inside front and back.

Vuillaume’s interest in Guarnerius emerged as early as 1835-1840, particularly after his detailed study of Paganini’s « Cannone. »

This instrument is one of the last known by the violin maker. It bears the number 2870, out of a production of nearly 3,000 known examples – an exceptional achievement for a 19th-century maker, and the result of a workshop organized like a true factory, with master makers such as Derazey, Silvestre, Germain and Maucotel.

Vuillaume became the greatest French violin maker of the 19th century through his ability to combine a fascination with and detailed study of the Italian masters with a constant desire to experiment. His copies are the result of an almost scientific approach, as Vuillaume made moulds, recorded measurements, studied the varnish, the woods, the arches, and even the microstructure of antique instruments – often those acquired by the dealer Luigi Tarisio.

As his own instruments attest, he never satisfied himself with simply reproducing originals. He modified the arches, adjusted the outlines, lengthened the fingerboards and lowered the height of the fronts to meet the expectations of musicians and adapt to the new repertoire.

These two instruments provide us a new testimony into the duality of Vuillaume’s work – which alternated between honouring the old masters and introducing new ideas – and two examples of perfection in violin making.